Ligurian language

This article should specify the language of its non-English content, using {{lang}} or {{transl}} (or {{IPA}} or similar for phonetic transcriptions), with an appropriate ISO 639 code. (October 2020) |

| Ligurian / Genoese | |

|---|---|

| lìgure, zeneize/zeneise | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈliɡyre], [zeˈnejze] |

| Native to | Italy, Monaco, France |

| Region | Italy • Liguria • Southern Piedmont • Southwestern Lombardy • Western Emilia-Romagna • Southwestern Sardinia France • Southeastern Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur • Southern Corsica |

Native speakers | 500,000 (2002)[1] |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | Old Latin

|

| Dialects |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | lij |

| Glottolog | ligu1248 |

| Linguasphere | 51-AAA-oh & 51-AAA-og |

| |

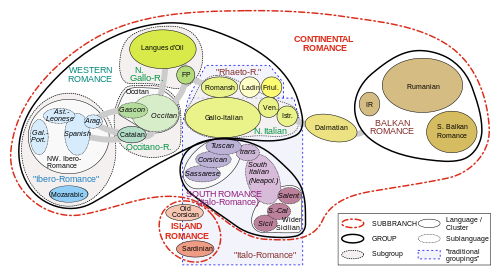

Ligurian or Genoese (lìgure or zeneize)[2] is a Gallo-Italic language spoken primarily in the territories of the former Republic of Genoa, now comprising the region of Liguria in Northern Italy, parts of the Mediterranean coastal zone of France, Monaco (where it is called Monegasque), the village of Bonifacio in Corsica, and in the villages of Carloforte on San Pietro Island and Calasetta on Sant'Antioco Island off the coast of southwestern Sardinia. It is part of the Gallo-Italic and Western Romance dialect continuum. Although part of Gallo-Italic, it exhibits several features of the Italo-Romance group of central and southern Italy. Zeneize (literally "for Genoese"), spoken in Genoa, the capital of Liguria, is the language's prestige dialect on which the standard is based.

There is a long literary tradition of Ligurian poets and writers that goes from the 13th century to the present, such as Luchetto (the Genoese Anonym), and .

Geographic extent and status[]

Ligurian does not enjoy an official status in Italy. Hence, it is not protected by law.[3] Historically, Genoese (the dialect spoken in the city of Genoa) is the written koiné, owing to its semi-official role as language of the Republic of Genoa, its traditional importance in trade and commerce, and its vast literature.

Like other regional languages in Italy, the use of Ligurian and its dialects is in rapid decline. ISTAT[4] (the Italian central service of statistics) claims that in 2012, only 9% of the population used a language other than standard Italian with friends and family, which decreases to 1.8% with strangers. Furthermore, according to ISTAT, regional languages are more commonly spoken by uneducated people and the elderly, mostly in rural areas. Liguria is no exception. One can reasonably suppose the age pyramid to be strongly biased toward the elderly who were born before World War II, with proficiency rapidly approaching zero for newer generations. Compared to other regional languages of Italy, Ligurian has experienced a significantly smaller decline which could have been a consequence of its status or the early decline it underwent in the past. The language itself is actively preserved by various groups.

Buio Pesto, a popular music group, has been composing songs entirely in the language since 1995.

Because of the importance of Genoese trade, Ligurian was once spoken well beyond the borders of the modern province. It has since given way to standard varieties, such as Standard Italian and French. In particular, the language is traditionally spoken in coastal, northern Tuscany, southern Piedmont (part of the province of Alessandria), western extremes of Emilia-Romagna (some areas in the province of Piacenza), and in Carloforte on San Pietro Island and Calasetta on Sant'Antioco Island off of southwestern Sardinia (known as Tabarchino), where its use is ubiquitous and increasing. It is also spoken in the department of the Alpes-Maritimes of France (mostly the Côte d'Azur from the Italian border to and including Monaco), in the town of Bonifacio at the southern tip of the French island of Corsica, and by a large community in Gibraltar (UK). It has been adopted formally in Monaco under the name Monégasque – locally, Munegascu – but without the status of official language (that is French). Monaco is the only place where a variety of Ligurian is taught in school.

The Mentonasc dialect, spoken in the East of the County of Nice, is considered to be a transitional Occitan dialect to Ligurian; conversely, Roiasc and Pignasc spoken further North in the Eastern margin of the County are Ligurian dialects with Occitan influences.

Description[]

As a Gallo-Italic language, Ligurian is most closely related to the Lombard, Piedmontese and Emilian-Romagnol languages, all of which are spoken in neighboring provinces. Unlike the aforementioned languages, however, it exhibits distinct Italian features. No link has been demonstrated by linguistic evidence between Romance Ligurian and the Ligurian language of the ancient Ligurian populations, in the form of a substrate or otherwise. Only the toponyms are known to have survived from ancient Ligurian, the name Liguria itself being the most obvious example.

Variants[]

Variants of the Ligurian language are:

- (in Bonifacio, Corsica)

- Brigasc (in La Brigue and Briga Alta)

- † (in Provence)

- Genoese (main Ligurian variant, spoken in Genoa)

- † (in Gibraltar)

- † (in Spain)

- † (in Genoa)

- Intemelio (in Sanremo and Ventimiglia)

- Monégasque (in Monaco)

- or Oltregiogo Ligurian (North of Genoa, mainly in Val Borbera and Novi Ligure)

- Royasc (in Upper Roya Valley, between Italy and France)

- (in La Spezia)

- Tabarchino (in Calasetta and Carloforte, Sardinia)

- (in Tende)

Phonology[]

Consonants[]

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | voiceless | p | t | k | ||

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | |||

| Affricate | voiceless | t͡ʃ | ||||

| voiced | d͡ʒ | |||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ | ||

| voiced | v | z | ʒ | |||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | ||

| Trill | r | |||||

| Approximant | lateral | l | ||||

| semivowel | j | w | ||||

Semivowels occur as allophones of /i/ and /u/, as well as in diphthongs. A /w/ sound occurs when a [u] sound occurs after a consonant, or before a vowel (i.e poeivan [pwejvaŋ]), as well as after a q sound, [kw].

Vowels[]

| Front | Central | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i iː | y yː | u uː | |

| Mid | e eː | ø øː | ||

| ɛ ɛː | ɔ ɔː | |||

| Open | a aː | |||

Diphthong sounds include ei [ej] and òu [ɔw].[5]

Alphabet[]

No universally accepted orthography exists for Ligurian. Genoese, the prestige dialect, has two main orthographic standards.

One, known as grafia unitäia (unitary orthography), has been adopted by the Ligurian-language press – including the Genoese column of the largest Ligurian press newspaper, Il Secolo XIX – as well as a number of other publishing houses and academic projects.[6][7][8][9] The other, proposed by the cultural association and the Academia Ligustica do Brenno is the self-styled grafia ofiçiâ (official orthography).[10][11] The two orthographies mainly differ in their usage of diacritics and doubled consonants.

The Ligurian alphabet is based on the Latin alphabet, and consists of 25 letters: ⟨a⟩, ⟨æ⟩, ⟨b⟩, ⟨c⟩, ⟨ç⟩, ⟨d⟩, ⟨e⟩, ⟨f⟩, ⟨g⟩, ⟨h⟩, ⟨i⟩, ⟨l⟩, ⟨m⟩, ⟨n⟩, ⟨ñ⟩ or ⟨nn-⟩, ⟨o⟩, ⟨p⟩, ⟨q⟩, ⟨r⟩, ⟨s⟩, ⟨t⟩, ⟨u⟩, ⟨v⟩, ⟨x⟩, ⟨z⟩.

The ligature ⟨æ⟩ indicates the sound /ɛː/, as in çit(t)æ 'city' /siˈtɛː/. The c-cedilla ⟨ç⟩, used for the sound /s/, generally only occurs before ⟨e⟩ or ⟨i⟩, as in riçetta 'recipe' /riˈsɛtta/. The letter ⟨ñ⟩, also written as ⟨nn-⟩ (or more rarely ⟨n-n⟩, ⟨n-⟩, ⟨nh⟩, or simply ⟨⟩), represents the velar nasal /ŋ/ before or after vowels, such as in canpaña 'bell' /kɑŋˈpɑŋŋɑ/, or the feminine indefinite pronoun uña /ˈyŋŋɑ/.

There are five diacritics, whose precise usage varies between orthographies. They are:

- The acute accent ⟨´⟩, can be used for ⟨é⟩ and ⟨ó⟩ to represent the sounds /e/ and /u/.

- The grave accent ⟨`⟩, can be used on the stressed vowels ⟨à⟩ /a/, ⟨è⟩ /ɛ/, ⟨ì⟩ /i/, ⟨ò⟩ /ɔ/, and ⟨ù⟩ /y/.

- The circumflex ⟨ˆ⟩, used for the long vowels ⟨â⟩ /aː/, ⟨ê⟩ /eː/, ⟨î⟩ /iː/, ⟨ô⟩ /uː/, and ⟨û⟩ /yː/ at the end of a word.

- The diaeresis ⟨¨⟩, used analogously to the circumflex to mark long vowels, but within a word: ⟨ä⟩ /aː/, ⟨ë⟩ /eː/, ⟨ï⟩ /iː/, and ⟨ü⟩ /yː/. It is also used to mark the long vowel ⟨ö⟩ /ɔː/, in any position.

The multigraphs are:

- ⟨cs⟩, used for the sound /ks/ as in bòcs 'box' /bɔks/.

- ⟨eu⟩, for /ø/.

- ⟨ou⟩, for /ɔw/.

- ⟨scc⟩ (written as ⟨sc-c⟩ in older orthographies) which indicates the sound /ʃtʃ/.

Vocabulary[]

Some basic vocabulary, in the spelling of the Genoese Academia Ligustica do Brenno:

| Ligurian | English | Italian | French | Spanish | Romanian | Catalan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| péi or péia, pl. péie | pear, pears | pera, pere | poire, poires | pera, peras | pară, pere | pera, peres |

| mei or méia, pl. méie | apple, apples | mela, mele | pomme, pommes | manzana, manzanas | măr, mere | poma, pomes |

| çetrón | lemon | limone | citron | limón | lămâie | llimona |

| fîgo | fig | fico | figue | higo | figa | |

| pèrsego | peach | pesca | pêche | durazno | piersică | préssec |

| frambôasa | raspberry | lampone | framboise | frambuesa | gerd | |

| çêxa | cherry | ciliegia | cerise | cereza | cireaşă | cirera |

| meréllo | strawberry | fragola | fraise | fresa | căpșună | maduixa |

| nôxe | (wal)nut | noce | noix | nuez | nucă | nou |

| nissêua | hazelnut | nocciola | noisette | avellana | avellana | |

| bricòccalo | apricot | albicocca | abricot | albaricoque | albercoc | |

| ûga | grape | uva | raisin | uva | raïm | |

| pigneu | pine nut | pinolo | pignon de pin | piñón | pinyó | |

| tomâta | tomato | pomodoro | tomate | tomate | tomàquet | |

| articiòcca | artichoke | carciofo | artichaut | alcachofa | escarxofa | |

| êuvo | egg | uovo | œuf | huevo | ou | ou |

| cà or casa | home, house | casa | maison, domicile | casa | casă | casa or ca |

| ciæo | clear or light | chiaro | clair | claro | clar | clar |

| éuggio | eye | occhio | œil | ojo | ochi | ull |

| bócca | mouth | bocca | bouche | boca | boca | |

| tésta | head | testa | tête | cabeza | ţeastă | cap |

| schénn-a | back | schiena | dos | espalda | spinare | esquena |

| bràsso | arm | braccio | bras | brazo | braţ | braç |

| gànba | leg | gamba | jambe | pierna | gambă | cama |

| cheu | heart | cuore | coeur | corazón | inimă | cor |

| arvî | to open | aprire | ouvrir | abrir | deschidere | obrir |

| serrâ | to close | chiudere | fermer | cerrar | închidere | tancar |

See also[]

- Sivèro, Dàvide, The Ligurian Dialect of the Padanian Language: A Concise Grammar (PDF), Romania Minor

- Jean-Philippe Dalbera, Les parlers des Alpes Maritimes : étude comparative, essai de reconstruction [thèse], Toulouse: Université de Toulouse 2, 1984 [éd. 1994, Londres: Association Internationale d’Études Occitanes]

- Werner Forner, "Le mentonnais entre toutes les chaises ? Regards comparatifs sur quelques mécanismes morphologiques" [Caserio & al. 2001: 11–23]

- Intemelion (revue), No. 1, Sanremo, 1995.

References[]

- ^ Ligurian / Genoese at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ^ https://omniglot.com/writing/genoese.htm Omniglot – Genoese

- ^ Legge 482, voted on Dec 15, 1999 does not mention Ligurian as a regional language of Italy.

- ^ "L'uso della lingua italiana, dei dialetti e di altre lingue in Italia". www.istat.it (in Italian). 2018-03-09. Retrieved 2018-08-22.

- ^ Toso, Fiorenzo (1997). Grammatica del genovese- Varietà urbana e di koiné. Recco: Le Mani- Microart's edizioni.

- ^ Acquarone, Andrea (13 December 2015). "O sciòrte o libbro de Parlo Ciæo, pe chi gh'è cao a nòstra lengua" [The anthology of Parlo Ciæo is now out, for those who love our language]. Il Secolo XIX (in Ligurian). Genoa, Italy. Archived from the original on 11 August 2020. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ "GEPHRAS -- Genoese-Italian Phraseological Dictionary". University of Innsbruck. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ "Catalogo poesia" [Catalogue of poetry] (in Italian). Editrice Zona. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ "Biblioteca zeneise" [Genoese library] (in Italian and Ligurian). De Ferrari editore. Archived from the original on 11 August 2020. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ "Grafîa ofiçiâ" [Official orthography] (in Ligurian). Academia Ligustica do Brenno. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ^ Bampi, Franco (2009). Grafîa ofiçiâ. Grafia ufficiale della lingua genovese. Bolezùmme (in Ligurian and Italian). Genoa, Italy: S.E.S. – Società Editrice Sampierdarenese. ISBN 978-8889948163.

External links[]

| Ligurian language edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

![]() Wikisource has original text related to this article: Ligurian language wikisource

Wikisource has original text related to this article: Ligurian language wikisource

- Associazione O Castello (in Italian and Ligurian)

- Académia Ligùstica do Brénno (in Ligurian)

- "Official Orthography and Alphabet" proposed by the Académia Ligùstica do Brénno (in Ligurian)

- A Compagna (in Italian)

- GENOVÉS.com.ar (English version) – Ligurian language & culture, literature, photos and resources to learn Ligurian (in English)

- GENOVÉS.com.ar (Homepage in Ligurian and Spanish) (in Spanish)

- Ligurian poetry and prose

- Ligurian dictionaries in Spanish and English to download for free

- Ligurian basic lexicon at the Global Lexicostatistical Database

- The Firefox browser in Ligurian

- The Opera browser in Ligurian

- Ligurian language (Romance)

- Gallo-Italic languages

- Languages of Italy

- Languages of Liguria

- Languages of Piedmont

- Languages of Lombardy

- Languages of Emilia-Romagna

- Languages of Sardinia

- Languages of Monaco

- Languages of France

- Languages of Argentina