List of South American dinosaurs

This is a list of dinosaurs whose remains have been recovered from South America.

Criteria for inclusion[]

- The creature must appear on the List of dinosaur genera

- Fossils of the creature must have been found in South America

- This list is a complement to Category:Dinosaurs of South America

List of South American dinosaurs[]

Valid genera[]

| Name | Year | Formation | Location | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

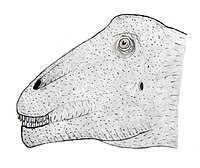

| Abelisaurus | 1985 | Anacleto Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian) | Only known from a single partial skull |

| |

| Achillesaurus | 2007 | Bajo de la Carpa Formation (Late Cretaceous, Santonian) | Potentially a junior synonym of Alvarezsaurus[1] |

| |

| Adamantisaurus | 2006 | Adamantina Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian) | Derived for a titanosaur as indicated by the ball-and-socket articulations of its caudal vertebrae |

| |

| Adeopapposaurus | 2009 | Cañón del Colorado Formation (Early Jurassic, Hettangian to Pliensbachian) | May have had a keratinous beak based on the shape of its jaw bones |

| |

| Aeolosaurus | 1987 | Angostura Colorada Formation, Lago Colhué Huapí Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian) | Known from the remains of several individuals |

| |

| Aerosteon | 2009 | Plottier Formation (Late Cretaceous, Santonian) | Its bones were extensively pneumatized, suggesting an air sac system like those of modern birds |

| |

| Agustinia | 1999 | Lohan Cura Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian to Albian) | Originally described as possessing long, vaguely-stegosaur like spikes, although these turned out to be fragments of ribs and other bones[2] | ||

| Alnashetri | 2012 | Candeleros Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian) | The oldest alvarezsaurid known from South America |

| |

| Alvarezsaurus | 1991 | Bajo de la Carpa Formation (Late Cretaceous, Santonian) | One of the largest known alvarezsaurids |

| |

| Amargasaurus | 1991 | La Amarga Formation (Early Cretaceous, Barremian to Aptian) | Possessed two parallel rows of backward-pointing spines on its neck |

| |

| Amargatitanis | 2007 | La Amarga Formation (Early Cretaceous, Barremian) | Originally described as a titanosaur[3] although it has since been reinterpreted as a dicraeosaurid[4] |

| |

| Amazonsaurus | 2003 | Itapecuru Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian to Albian) | Had tall neural spines on its caudal vertebrae |

| |

| Amygdalodon | 1947 | Cerro Carnerero Formation (Early Jurassic, Toarcian) | Its teeth were shaped like almonds |

| |

| Anabisetia | 2002 | Lisandro Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian to Turonian) | Four specimens are known but none of them preserve a skull |

| |

| Andesaurus | 1991 | Candeleros Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian) | Several osteological features indicate a basal position within the Titanosauria |

| |

| Aniksosaurus | 2006 | Bajo Barreal Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian to Turonian) | Bone bed remains suggest a gregarious lifestyle[5] |

| |

| Antarctosaurus | 1929 | Anacleto Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian) | Multiple specimens have been assigned to this genus, including some from outside South America, but most may not represent the same taxon |

| |

| Aoniraptor | 2016 | Huincul Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian to Turonian) | Potentially synonymous with Gualicho | ||

| Arackar | 2021 | Hornitos Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian) | The most complete sauropod known from South America | ||

| Aratasaurus | 2020 | Romualdo Formation (Early Cretaceous, Albian) | All three of its toes were symmetric |

| |

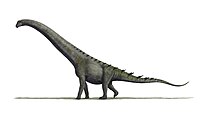

| Argentinosaurus | 1993 | Huincul Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian to Turonian) | May be the largest known dinosaur |

| |

| Argyrosaurus | 1893 | Lago Colhué Huapí Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian) | Several remains were historically assigned to this genus, but only the holotype can be confidently assigned to it[6] |

| |

| Arrudatitan | 2021 | Adamantina Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian) | Its tail probably curved strongly downward, with the tip held very low to the ground[7] | ||

| Asfaltovenator | 2019 | Cañadón Asfalto Formation (Early Jurassic, Toarcian) | Combines traits of both megalosauroids and allosauroids. Its describers suggest paraphyly of the former group[8] |

| |

| Atacamatitan | 2011 | (Late Cretaceous) | Only known from a single, fragmentary skeleton |

| |

| Aucasaurus | 2002 | Anacleto Formation (Late Cretaceous, Santonian to Campanian) | Known from almost the entire skeleton, including most of the skull |

| |

| Austrocheirus | 2010 | Cerro Fortaleza Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian) | Unusually for an abelisauroid, its arms were relatively long |

| |

| Austroposeidon | 2016 | Presidente Prudente Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian) | The largest dinosaur known from Brazil |

| |

| Austroraptor | 2008 | Allen Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian) | Possessed an elongated snout paralleling that of spinosaurids |

| |

| Baalsaurus | 2018 | Portezuelo Formation (Late Cretaceous, Turonian to Coniacian) | Had a squared-off dentary with its teeth crowded to the front | ||

| Bagualia | 2020 | Cañadón Asfalto Formation (Early Jurassic, Toarcian) | Represents an early radiation of eusauropods that displaced earlier basal sauropodomorphs after a global warming event[9] | ||

| Bagualosaurus | 2018 | Santa Maria Formation (Late Triassic, Carnian) | Its hindlimbs were very robust |

| |

| Bajadasaurus | 2019 | Bajada Colorada Formation (Early Cretaceous, Berriasian to Valanginian) | Possessed elongated, forward-pointing spines erupting in pairs from the neck |

| |

| Barrosasaurus | 2009 | Anacleto Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian) | Only known from three vertebrae but are well-preserved enough to warrant recognition as a distinct genus | ||

| Baurutitan | 2005 | (Late Cretaceous, Campanian) | Described from an associated series of nineteen vertebrae | ||

| Berthasaura | 2021 | Goio-Erê Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian to Albian) | Possessed a short, toothless beak, indicating a herbivorous or omnivorous diet |

| |

| Bicentenaria | 2012 | Candeleros Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian) | Several individuals were preserved together, suggesting a gregarious lifestyle[10] |

| |

| Bonapartenykus | 2012 | Allen Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian) | Its holotype was preserved with two eggs that may have been within its oviducts when it died[11] |

| |

| Bonapartesaurus | 2017 | Allen Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian) | Represents a saurolophine dispersal event from North America[12] | ||

| Bonatitan | 2004 | Allen Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian) | Analysis of its inner ear suggests a decreased range of head movements compared to other sauropods[13] | ||

| Bonitasaura | 2004 | Bajo de la Carpa Formation (Late Cretaceous, Santonian) | The proportions of its body were similar to those of diplodocoids, likely through convergent evolution |

| |

| Brachytrachelopan | 2005 | Cañadón Calcáreo Formation (Late Jurassic, Oxfordian to Tithonian) | Possessed the shortest neck of any known sauropod |

| |

| Brasilotitan | 2013 | Adamantina Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian) | Had an L-shaped dentary similiar to that of Antarctosaurus and Bonitasaura | ||

| Bravasaurus | 2020 | (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian) | Discovered close to a large concentration of titanosaur eggs | ||

| Buitreraptor | 2005 | Candeleros Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian to Turonian) | May have been a pursuit predator due to its long legs[14] |

| |

| Buriolestes | 2016 | Santa Maria Formation (Late Triassic, Carnian) | Completely carnivorous due to its serrated teeth |

| |

| Campylodoniscus | 1961 | Bajo Barreal Formation? (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian) | Only known from a single maxilla with seven teeth | ||

| Carnotaurus | 1985 | La Colonia Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian) | Possessed a pair of short horns on the top of its skull |

| |

| Cathartesaura | 2005 | Huincul Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian) | Had a well-muscled neck although it could not move strongly up or down | ||

| Chilesaurus | 2015 | Toqui Formation (Late Jurassic, Tithonian) | Combines traits of theropods, sauropodomorphs, and ornithischians, with far-reaching implications for the evolution of the Dinosauria |

| |

| Choconsaurus | 2017 | Huincul Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian) | One of the more completely known basal titanosaurs | ||

| Chromogisaurus | 2010 | Ischigualasto Formation (Late Triassic, Carnian) | Its discovery suggests that early dinosaurs were more diverse than previously thought | ||

| Chubutisaurus | 1975 | Cerro Barcino Formation (Early Cretaceous, Albian) | Unusually, its forelimbs were shorter than its hindlimbs[15] |

| |

| Clasmodosaurus | 1898 | Bajo Barreal Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian to Turonian) | Similarly to Bonitasaura, its teeth were polygonal in cross-section | ||

| Coloradisaurus | 1990 | Los Colorados Formation (Late Triassic, Norian) | Originally called Coloradia, although that genus name is occupied by a moth | ||

| Comahuesaurus | 2012 | Lohan Cura Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian to Albian) | Its holotype was originally assigned to Limaysaurus, but it was named as a separate genus due to possessing a certain feature in its vertebrae | ||

| Condorraptor | 2005 | Cañadón Asfalto Formation (Early Jurassic, Toarcian) | Closely related to the coeval Piatnitzkysaurus but could be distinguished by several osteological features |

| |

| Dreadnoughtus | 2014 | Cerro Fortaleza Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian) | The heaviest land animal whose mass can be calculated with reasonable certainty |

| |

| Drusilasaura | 2011 | Bajo Barreal Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian to Turonian) | Potentially the oldest known member of the lognkosaurian lineage[16] |

| |

| Ekrixinatosaurus | 2004 | Candeleros Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian) | Had robust bones, indicating a massive build and a greater resistance to injuries[17] |

| |

| Elaltitan | 2012 | Bajo Barreal Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian to Turonian) | Extremely large due to its long femur | ||

| Eoabelisaurus | 2012 | Cañadón Asfalto Formation (Early Jurassic, Toarcian) | Shows a transitional arm morphology for an abelisauroid, with a shortened lower arm and hand, but an unreduced humerus |

| |

| Eodromaeus | 2011 | Ischigualasto Formation (Late Triassic, Carnian | Well-adapted for cursoriality despite its early age[18] |

| |

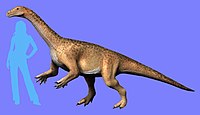

| Eoraptor | 1993 | Ischigualasto Formation (Late Triassic, Carnian) | Possessed different types of teeth, suggesting it was omnivorous |

| |

| Epachthosaurus | 1990 | Bajo Barreal Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian to Turonian) | Its caudal vertebrae were procoelous; i.e. concave at the front and convex at the back | ||

| Erythrovenator | 2021 | Candelária Formation (Late Triassic, Carnian to Norian) | Known from the Riograndia Assemblage Zone, an area which is unusually dominated by cynodonts |

| |

| Futalognkosaurus | 2007 | Portezuelo Formation (Late Cretaceous, Coniacian) | Possessed meter-deep cervical vertebrae with distinctive shark fin-shaped neural spines |

| |

| Gasparinisaura | 1996 | Anacleto Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian) | Known from specimens of both adults and juveniles |

| |

| Genyodectes | 1901 | Cerro Barcino Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian to Albian) | Had extremely large and protruding teeth |

| |

| Giganotosaurus | 1995 | Candeleros Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian) | One of the largest known terrestrial carnivorous dinosaurs |

| |

| Gondwanatitan | 1999 | Adamantina Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian) | For a titanosaur, it had relatively gracile limb bones |

| |

| Guaibasaurus | 1999 | Caturrita Formation (Late Triassic, Norian) | Combines features of both early theropods and sauropodomorphs |

| |

| Gualicho | 2016 | Huincul Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian to Turonian) | Originally described as having highly reduced arms with only two fingers, convergent with tyrannosaurids, although one study suggests a third finger was present[19] |

| |

| Huinculsaurus | 2020 | Huincul Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian to Turonian) | The youngest known elaphrosaurine |

| |

| Ilokelesia | 1998 | Huincul Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian) | Its skull retains some basal abelisauroid traits |

| |

| Ingentia | 2018 | Quebrada del Barro Formation (Late Triassic, Rhaetian) | The earliest known very large sauropodomorph[20] | ||

| Irritator | 1996 | Romualdo Formation (Early Cretaceous, Albian) | May have been the apex predator of its habitat, hunting both aquatic and terrestrial prey[21] |

| |

| Isaberrysaura | 2017 | Los Molles Formation (Middle Jurassic, Bajocian) | Potentially a basal stegosaur[22] | ||

| Isasicursor | 2019 | Chorrillo Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian) | Four individuals of different ages were found together, suggesting it lived in herds[23] | ||

| Itapeuasaurus | 2019 | Alcântara Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian) | Only known from six vertebrae | ||

| Kaijutitan | 2019 | Sierra Barrosa Formation (Late Cretaceous, Coniacian) | One of the latest-surviving basal titanosaurs | ||

| Katepensaurus | 2013 | Bajo Barreal Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian to Turonian) | Distinguished by a certain opening in its dorsal vertebrae | ||

| Kurupi | 2021 | Marília Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian) | Would have had a stiff tail as indicated by the anatomy of its caudal vertebrae |

| |

| Lajasvenator | 2020 | Mulichinco Formation (Early Cretaceous, Valanginian) | One of the smallest known allosauroids |

| |

| Lapampasaurus | 2012 | Allen Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian) | Known from a partial skeleton lacking the skull | ||

| Laplatasaurus | 1929 | Allen Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian) | Osteoderms have been assigned to this taxon although this referral is uncertain | ||

| Laquintasaura | 2014 | La Quinta Formation (Early Jurassic, Hettangian) | One study recovered it as a basal thyreophoran[24] despite the fact no osteoderms have been found |

| |

| Lavocatisaurus | 2018 | Rayoso Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian to Albian) | May have possessed a keratinous beak[25] |

| |

| Leinkupal | 2014 | Bajada Colorada Formation (Early Cretaceous, Berriasian to Valanginian) | The youngest known diplodocid | ||

| Leonerasaurus | 2011 | (Early Jurassic?) | Has an unusual combination of basal and derived traits |

| |

| Lessemsaurus | 1999 | Los Colorados Formation (Late Triassic, Norian) | Grew very large despite lacking the anatomical traits usually seen as supporting gigantism[20] | ||

| Leyesaurus | 2011 | Quebrada del Barro Formation (Early Jurassic) | Its teeth were moderately heterodont | ||

| Ligabueino | 1996 | La Amarga Formation (Early Cretaceous, Barremian to Aptian) | Known from a single, very small, juvenile skeleton | ||

| Ligabuesaurus | 2006 | Lohan Cura Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian to Albian) | Its forelimbs were extremely long, with similar proportions to those of brachiosaurids[26] |

| |

| Limaysaurus | 2004 | Candeleros Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian) | Possessed elongated neural spines on its dorsal vertebrae | ||

| Llukalkan | 2021 | Bajo de la Carpa Formation (Late Cretaceous, Santonian) | May have had a keen sense of hearing due to the shape of its ear[27] | ||

| Loncosaurus | 1899 | Cardiel Formation?/? (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian) | Poorly known | ||

| Loricosaurus | 1929 | Allen Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian) | Potentially synonymous with Neuquensaurus or Saltasaurus | ||

| Lucianovenator | 2017 | Quebrada del Barro Formation (Late Triassic, Norian to Rhaetian) | Only known from a few bones, but it is nonetheless more common than other Rhaetian theropods |

| |

| Macrocollum | 2018 | Candelária Formation (Late Triassic, Norian) | One of the oldest sauropodomorphs with an extremely elongated neck |

| |

| Macrogryphosaurus | 2007 | Sierra Barrosa Formation (Late Cretaceous, Coniacian) | Preserves a series of mineralized plates along the side of the torso |

| |

| Mahuidacursor | 2019 | Bajo de la Carpa Formation (Late Cretaceous, Santonian) | Its holotype was sexually mature but not fully grown | ||

| Malarguesaurus | 2008 | Los Bastos Formation (Late Cretaceous, Coniacian) | Large and robustly built | ||

| Manidens | 2011 | Cañadón Asfalto Formation (Early Jurassic, Toarcian) | May have been arboreal due to the structure of its feet, with toes adapted for grasping[28] |

| |

| Mapusaurus | 2006 | Huincul Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian to Turonian) | Seven specimens of different growth stages are known, possibly suggesting that lived and/or hunted in packs |

| |

| Maxakalisaurus | 2006 | Adamantina Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian) | Unusually for a sauropod, it had ridged teeth |

| |

| Megaraptor | 1998 | Portezuelo Formation (Late Cretaceous, Turonian to Coniacian) | Possessed a large, strongly curved claw on its first finger |

| |

| Mendozasaurus | 2003 | Sierra Barrosa Formation (Late Cretaceous, Coniacian) | Had spherical osteoderms that were probably located in rows along the flanks[29] | ||

| Menucocelsior | 2022 | Allen Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian) | Coexisted with multiple other titanosaurs that may have niche-partitioned[30] | ||

| Microcoelus | 1893 | Bajo de la Carpa Formation (Late Cretaceous, Santonian to Campanian) | May be a synonym of Neuquensaurus | ||

| Mirischia | 2004 | Romualdo Formation (Early Cretaceous, Albian) | Its holotype preserves an intestine |

| |

| Murusraptor | 2016 | Sierra Barrosa Formation (Late Cretaceous, Coniacian) | Had a brain morphology similiar to that of tyrannosaurids but its sensory capabilities were closer to the level of allosauroids[31] |

| |

| Mussaurus | 1979 | Laguna Colorada Formation (Early Jurassic, Sinemurian) | Multiple specimens from different growth stages are known. Juveniles may have been quadrupedal and shifted to bipedality as adults[32] |

| |

| Muyelensaurus | 2007 | Plottier Formation (Late Cretaceous, Coniacian to Santonian) | Relatively gracile for a titanosaur | ||

| Narambuenatitan | 2011 | Anacleto Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian) | Its neural spines are very similar to those of Epachthosaurus |

| |

| Neuquenraptor | 2005 | Portezuelo Formation (Late Cretaceous, Coniacian) | Potentially synonymous with Unenlagia[33] |

| |

| Neuquensaurus | 1992 | Anacleto Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian) | One of the smallest known titanosaurs | ||

| Nhandumirim | 2019 | Santa Maria Formation (Late Triassic, Carnian) | Originally described as a theropod[34] but has since been reinterpreted as a sauropodomorph[35] | ||

| Niebla | 2020 | Allen Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian) | Had a uniquely-built scapulocoracoid that is only found in this genus and Carnotaurus |

| |

| Ninjatitan | 2021 | Bajada Colorada Formation (Early Cretaceous, Berriasian to Valanginian) | The oldest known titanosaur | ||

| Noasaurus | 1980 | Lecho Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian) | Originally mistakenly believed to have possessed a dromaeosaurid-like sickle claw |

| |

| Nopcsaspondylus | 2007 | Candeleros Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian) | Named from a single, lost vertebra | ||

| Notoceratops | 1918 | Laguna Palacios Formation?/? (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian) | If a ceratopsian it would be the only South American member of the group | ||

| Notocolossus | 2016 | Plottier Formation (Late Cretaceous, Coniacian to Santonian) | Unusually for a sauropod, its unguals were truncated |

| |

| Notohypsilophodon | 1998 | Bajo Barreal Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian to Turonian) | Only known from a skull-less, juvenile skeleton | ||

| Nullotitan | 2019 | Chorrillo Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian) | Would have niche-partitioned with smaller ornithopods | ||

| Orkoraptor | 2008 | Cerro Fortaleza Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian) | Had highly specialized dentition similar to that of maniraptorans |

| |

| Overoraptor | 2020 | Huincul Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian) | Shows adaptations for both flight and cursoriality |

| |

| Overosaurus | 2013 | Bajo de la Carpa Formation (Late Cretaceous, Santonian) | One of the smallest known aeolosaurins |

| |

| Padillasaurus | 2015 | Paja Formation (Early Cretaceous, Barremian) | Originally described as a brachiosaurid[36] although it could also be a somphospondylian[37] | ||

| Pampadromaeus | 2011 | Santa Maria Formation (Late Triassic, Carnian) | Some features of its jaws are similar to those of theropods |

| |

| Pamparaptor | 2011 | Portezuelo Formation (Late Cretaceous, Turonian to Coniacian) | Had a troodontid-like metatarsal |

| |

| Panamericansaurus | 2010 | Allen Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian) | Known from a single partial skeleton | ||

| Pandoravenator | 2017 | Cañadón Calcáreo Formation (Late Jurassic, Oxfordian to Tithonian) | Inconsistent in phylogenetic placement | ||

| Panphagia | 2009 | Ischigualasto Formation (Late Triassic, Carnian) | Was omnivorous as indicated by its heterodont dentition |

| |

| Patagonykus | 1996 | Portezuelo Formation (Late Cretaceous, Turonian to Coniacian) | Its discovered allowed researchers to connect Alvarezsaurus and parvicursorines[38] |

| |

| Patagosaurus | 1979 | Cañadón Asfalto Formation (Early Jurassic, Toarcian) | Known from remains of adults and juveniles, depicting how various features developed in sauropods as they aged |

| |

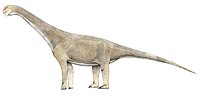

| Patagotitan | 2017 | Cerro Barcino Formation (Early Cretaceous, Albian) | One of the largest dinosaurs known from reasonably complete remains |

| |

| Pellegrinisaurus | 1996 | Allen Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian) | May have lived inland unlike other contemporaneous titanosaurs[39] | ||

| Petrobrasaurus | 2011 | Plottier Formation (Late Cretaceous, Coniacian to Santonian) | Shares somes features with lognkosaurs, but its membership within this clade cannot be confirmed |

| |

| Piatnitzkysaurus | 1979 | Cañadón Asfalto Formation (Early Jurassic, Toarcian) | One of the few early theropods with a well-preserved braincase |

| |

| Pilmatueia | 2018 | Mulichinco Formation (Early Cretaceous, Valanginian) | Closely related to Amargasaurus[40] | ||

| Pitekunsaurus | 2008 | Anacleto Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian) | Known from several bones from different parts of the body, including a braincase |

| |

| Powellvenator | 2017 | Los Colorados Formation (Late Triassic, Norian) | Some of this genus' remains were originally associated with those of a pseudosuchian[41] | ||

| Puertasaurus | 2005 | Cerro Fortaleza Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian) | Large but only known from very few remains |

| |

| Punatitan | 2020 | (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian) | Contemporary with Bravasaurus but was most likely distantly related[42] | ||

| Pycnonemosaurus | 2002 | Unnamed formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian) | Potentially the largest known abelisaurid[43] |

| |

| Quetecsaurus | 2014 | Lisandro Formation (Late Cretaceous, Turonian) | Its humerus was uniquely-shaped |

| |

| Quilmesaurus | 2001 | Allen Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian) | Had porportionally robust legs despite its small size |

| |

| Rayososaurus | 1996 | Candeleros Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian) | Very similar to Rebbachisaurus despite only being known from scant remains | ||

| Rinconsaurus | 2003 | Bajo de la Carpa Formation (Late Cretaceous, Santonian) | Unusually, its caudal vertebrae had a repeating pattern of procoely, amphicoely, opisthocoely, and biconvex states |

| |

| Riojasaurus | 1969 | Los Colorados Formation (Late Triassic, Norian) | Although commonly depicted as quadrupedal, the structure of its shoulder girdle suggests it was bipedal |

| |

| Rocasaurus | 2000 | Allen Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian) | Small for a sauropod yet was very robust | ||

| Saltasaurus | 1980 | Lecho Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian) | Possessed osteoderms in the form of large round nodules connected by a mass of smaller plates |

| |

| Santanaraptor | 1999 | Romualdo Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian to Albian) | Preserves soft tissues including the remains of skin, muscle, and possibly blood vessels[44][45] | ||

| Sarmientosaurus | 2016 | Bajo Barreal Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian to Turonian) | Analysis of its inner ear suggests it held its head downwards, possibly indicating a preference for low-growing plants | ||

| Saturnalia | 1999 | Santa Maria Formation (Late Triassic, Carnian) | Known from three partial skeletons |

| |

| Secernosaurus | 1979 | Lago Colhué Huapí Formation, Los Alamitos Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian) | Some remains were originally misidentified as belonging to a southern species of Kritosaurus | ||

| Sektensaurus | 2019 | Lago Colhué Huapí Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian) | The first non-hadrosaurid ornithopod recovered from central Patagonia | ||

| Skorpiovenator | 2008 | Huincul Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian to Turonian) | Had an unusually short and deep skull |

| |

| Spectrovenator | 2020 | Quiricó Formation (Early Cretaceous, Barremian to Aptian) | Its holotype was found underneath a sauropod skeleton |

| |

| Staurikosaurus | 1970 | Santa Maria Formation (Late Triassic, Carnian to Norian) | May have been a rare component of its environment, with only two specimens known |

| |

| Stegouros | 2021 | Dorotea Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian) | Possessed a "macuahuitl" at the end of its tail, made of a connected "frond" of pointed osteoderms |

| |

| Tachiraptor | 2014 | La Quinta Formation (Early Jurassic, Hettangian) | Closely related to ceratosaurs and tetanurans[46] | ||

| Talenkauen | 2004 | Cerro Fortaleza Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian) | May have practiced parental care as an adult and a hatchling have been found together |

| |

| Tapuiasaurus | 2011 | Quiricó Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian) | One of the few titanosaurs of which a complete skull is known |

| |

| Tehuelchesaurus | 1999 | Cañadón Calcáreo Formation (Late Jurassic, Oxfordian to Tithonian) | Preserves impressions of scaly skin |

| |

| Thanos | 2020 | (Late Cretaceous, Santonian) | Only known from a single vertebra. The generic name honors the Marvel Comics villain Thanos |

| |

| Tralkasaurus | 2020 | Huincul Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian to Turonian) | Exhibits a conflict blend of characteristics from basal and derived abelisauroids | ||

| Tratayenia | 2018 | Bajo de la Carpa Formation (Late Cretaceous, Santonian) | Potentially the youngest known megaraptoran[47] | ||

| Traukutitan | 2011 | Bajo de la Carpa Formation (Late Cretaceous, Santonian) | Retained basal features in its caudal vertebrae despite its late age | ||

| Trigonosaurus | 2005 | (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian) | Before it was formally described, it had been informally referred to as the "Peirópolis titanosaur" | ||

| Triunfosaurus | 2017 | Rio Piranhas Formation (Early Cretaceous, Berriasian to Valanginian) | Originally described as a titanosaur[48] but similarities have been noted with basal somphospondylians[49] | ||

| Tyrannotitan | 2005 | Cerro Barcino Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian) | Unlike other carcharodontosaurids, its sacral and caudal vertebrae were not pneumatic |

| |

| Uberabatitan | 2008 | (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian) | Several individuals are known, some of which are very large | ||

| Unaysaurus | 2004 | Caturrita Formation (Late Triassic, Carnian to Norian) | Described as the first plateosaurid-grade sauropodomorph from Brazil |

| |

| Unenlagia | 1997 | Portezuelo Formation (Late Cretaceous, Coniacian) | Could potentially be adapted for flapping due to the structure of its shoulder girdle[50] |

| |

| Unquillosaurus | 1979 | Los Blanquitos Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian) | Has been suggested to be a dromaeosaurid[51] or a carcharodontosaurid[52] | ||

| Velocisaurus | 1991 | Bajo de la Carpa Formation (Late Cretaceous, Santonian) | Unusually, its third metatarsal is the thickest |

| |

| Vespersaurus | 2019 | (Late Cretaceous) | Possessed raised claws on its second and fourth toes, making it functionally monodactyl, a possible adaptation to its desert habitat |

| |

| Viavenator | 2016 | Bajo de la Carpa Formation (Late Cretaceous, Santonian) | May have relied on quick movements of its head and gaze stabilization when hunting |

| |

| Volkheimeria | 1979 | Cañadón Asfalto Formation (Early Jurassic, Toarcian) | Its neural spines were very low and flat | ||

| Willinakaqe | 2010 | Allen Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian) | As originally described, it represented a chimera of two different taxa, one of which was later named Bonapartesaurus[12] | ||

| Xenotarsosaurus | 1986 | Bajo Barreal Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian to Turonian) | Had an unusually-shaped astragalus and calcaneum | ||

| Yamanasaurus | 2019 | (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian) | The northernmost saltasaurine known to date[42] |

| |

| Ypupiara | 2021 | (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian) | May have been a piscivore due to the shape of its teeth[53] |

| |

| Zapalasaurus | 2006 | La Amarga Formation (Early Cretaceous, Hauterivian to Aptian) | Known from an incomplete skeleton, including several caudal vertebrae |

| |

| Zupaysaurus | 2003 | Los Colorados Formation (Late Triassic, Norian) | Although commonly depicted with head crests, they may in fact be misplaced lacrimal bones[54] |

|

Dubious, uncertain, and invalid genera[]

- Angaturama limai: Only known from the tip of the snout. It may belong to the contemporary Irritator, but it could also represent its own taxon.

- "Bayosaurus pubica": An abelisaurid known from partial postcranial remains.

- Gnathovorax cabreirai: Known from a well-preserved, almost complete specimen. It may not be a dinosaur.

- Herrerasaurus ischigualastensis: The type genus of a family of basal predators called herrerasaurids. They may represent early dinosaurs, possibly saurischians, but they could also be just outside Dinosauria.

- Oxalaia quilombensis: Potentially a junior synonym of Spinosaurus.

- Sanjuansaurus gordilloi: A herrerasaurid that, like the other members of its group, could be non-dinosaurian.

- Taurovenator violantei: Only known from a single postorbital, it may be a junior synonym of Mapusaurus.

- "Ubirajara jubatus": Known from a single specimen that preserves impressions of feathers, including display feathers on its sides. Its description was retracted before it could be published due to allegations that the specimen was illegally exported from Brazil.

Timeline[]

This is a timeline of selected dinosaurs from the list above. Time is measured in Ma, megaannum, along the x-axis. Carnivores are shown in red, herbivores in green and omnivores in blue.

See also[]

- List of birds of South America

References[]

- ^ Makovicky, P.J.; Apesteguía, S.N.; Gianechini, F.A. (2012). "A New Coelurosaurian Theropod from the La Buitrera Fossil Locality of Río Negro, Argentina". Fieldiana Life and Earth Sciences. 5: 90–98. doi:10.3158/2158-5520-5.1.90. S2CID 129758444.

- ^ Bellardini, F.; Cerda, I.A. (2017). "Bone histology sheds light on the nature of the "dermal armor" of the enigmatic sauropod dinosaur Agustinia ligabuei Bonaparte, 1999". The Science of Nature. 104 (1): 1. Bibcode:2017SciNa.104....1B. doi:10.1007/s00114-016-1423-7. PMID 27942797. S2CID 21654124.

- ^ Apesteguía, Sebastián (2007). "The sauropod diversity of the La Amarga Formation (Barremian), Neuquén (Argentina)". Gondwana Research. 12 (4): 533–546. Bibcode:2007GondR..12..533A. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2007.04.007.

- ^ Gallina, Pablo Ariel (2016). "Reappraisal Of The Early Cretaceous Sauropod Dinosaur Amargatitanis macni (Apesteguía, 2007), From Northwestern Patagonia, Argentina". Cretaceous Research. 64: 79–87. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2016.04.002.

- ^ Ibiricu, L. M.; Martínez, R. N. D.; Casal, G. A.; Cerda, I. A. (2013). Butler, Richard J (ed.). "The Behavioral Implications of a Multi-Individual Bonebed of a Small Theropod Dinosaur". PLOS ONE. 8 (5): e64253. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...864253I. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0064253. PMC 3655058. PMID 23691183.

- ^ Mannion, P. D.; Otero, A. (2012). "A reappraisal of the Late Cretaceous Argentinean sauropod dinosaur Argyrosaurus superbus, with a description of a new titanosaur genus". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 32 (3): 614–618. doi:10.1080/02724634.2012.660898. S2CID 86762374.

- ^ Vidal, Luciano da Silva; Pereira, Paulo Victor Luiz Gomes da Costa; Tavares, Sandra; Brusatte, Stephen L.; Bergqvist, Lílian Paglarelli; Candeiro, Carlos Roberto dos Anjos (2020). "Investigating the enigmatic Aeolosaurini clade: the caudal biomechanics of Aeolosaurus maximus (Aeolosaurini/Sauropoda) using the neutral pose method and the first case of protonic tail condition in Sauropoda". Historical Biology. 33 (9): 1836–1856. doi:10.1080/08912963.2020.1745791. S2CID 218822392.

- ^ Rauhut, Oliver W. M.; Pol, Diego (2019-12-11). "Probable basal allosauroid from the early Middle Jurassic Cañadón Asfalto Formation of Argentina highlights phylogenetic uncertainty in tetanuran theropod dinosaurs". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 18826. Bibcode:2019NatSR...918826R. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-53672-7. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6906444. PMID 31827108.

- ^ D. Pol; J. Ramezani; K. Gomez; J. L. Carballido; A. Paulina Carabajal; O. W. M. Rauhut; I. H. Escapa; N. R. Cúneo (2020). "Extinction of herbivorous dinosaurs linked to Early Jurassic global warming event". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 287 (1939): Article ID 20202310. doi:10.1098/rspb.2020.2310. PMC 7739499. PMID 33203331. S2CID 226982302.

- ^ Novas, F.E., Ezcurra, M.D., Agnolín, F.L., Pol, D. and Ortíz, R. (2012). "New Patagonian Cretaceous theropod sheds light about the early radiation of Coelurosauria." Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales, nueva serie, 14: 57–81.

- ^ Federico L. Agnolin; Jaime E. Powell; Fernando E. Novas & Martin Kundrát (June 2012). "New alvarezsaurid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from uppermost Cretaceous of north-western Patagonia with associated eggs". Cretaceous Research. 35: 33–56. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2011.11.014.

- ^ a b Cruzado-Caballero, P.; Powell, J. E. (2017). "Bonapartesaurus rionegrensis, a new hadrosaurine dinosaur from South America: implications for phylogenetic and biogeographic relations with North America". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 37 (In press): 1–16. doi:10.1080/02724634.2017.1289381. S2CID 90963879.

- ^ Carabajal, Ariana Paulina (2012). "Neuroanatomy of Titanosaurid Dinosaurs From the Upper Cretaceous of Patagonia, With Comments on Endocranial Variability Within Sauropoda". The Anatomical Record: Advances in Integrative Anatomy and Evolutionary Biology. 295 (12): 2141–2156. doi:10.1002/ar.22572. PMID 22961834. S2CID 24555402.

- ^ Gianechini, F. A.; Ercoli, M. D.; Díaz-Martinez, I. (2020). "Differential locomotor and predatory strategies of Gondwanan and derived Laurasian dromaeosaurids (Dinosauria, Theropoda, Paraves): Inferences from morphometric and comparative anatomical studies". Journal of Anatomy. 236 (5): 772−797. doi:10.1111/joa.13153. PMC 7163733. PMID 32023660.

- ^ G. del Corro. 1975. Un nuevo sauropodo del Cretácico Superior. Actas del Primer Congreso Argentino de Paleontologia y Bioestratigrafia 2:229-240

- ^ César Navarrete, Gabriel Casal and Rubén Martínez (2011). "Drusilasaura deseadensis gen. et sp. nov., a new titanosaur (Dinosauria-Sauropoda), of the Bajo Barreal Formation, Upper Cretaceous of north of Santa Cruz, Argentina" (PDF). Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia. 14 (1): 1–14. doi:10.4072/rbp.2011.1.01.

- ^ Juárez Valieri, R.D.; Porfiri, J.D.; Calvo, J.O. (2011). "New information on Ekrixinatosaurus novasi Calvo et al. 2004, a giant and massively-constructed Abelisauroid from the "Middle Cretaceous" of Patagonia". In Calvo; González; Riga; Porfiri; Dos Santos (eds.). Paleontología y dinosarios desde América Latina. pp. 161–169.

- ^ Kubo, Tai; Kubo, Mugino O. (2012-06-01). "Associated evolution of bipedality and cursoriality among Triassic archosaurs: a phylogenetically controlled evaluation". Paleobiology. 38 (3): 474–485. doi:10.1666/11015.1. ISSN 0094-8373. JSTOR 41684613. S2CID 85941954 – via jstor.

- ^ Ibrahim, Nizar; Sereno, Paul C.; Varricchio, David J.; Martill, David M.; Dutheil, Didier B.; Unwin, David M.; Baidder, Lahssen; Larsson, Hans C. E.; Zouhri, Samir; Kaoukaya, Abdelhadi (2020-04-21). "Geology and paleontology of the Upper Cretaceous Kem Kem Group of eastern Morocco". ZooKeys (928): 1–216. doi:10.3897/zookeys.928.47517. ISSN 1313-2970. PMC 7188693. PMID 32362741.

- ^ a b Apaldetti; Martínez, Ricardo N.; Cerda, Ignatio A.; Pol, Diego; Alcober, Oscar (2018). "An early trend towards gigantism in Triassic sauropodomorph dinosaurs". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2 (8): 1227–1232. doi:10.1038/s41559-018-0599-y. hdl:11336/89332. PMID 29988169. S2CID 49669597.

- ^ Aureliano, Tito; Ghilardi, Aline M.; Buck, Pedro V.; Fabbri, Matteo; Samathi, Adun; Delcourt, Rafael; Fernandes, Marcelo A.; Sander, Martin (May 3, 2018). "Semi-aquatic adaptations in a spinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil". Cretaceous Research. 90: 283–295. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2018.04.024. ISSN 0195-6671. S2CID 134353898.

- ^ Fenglu Han; Catherine A. Forster; Xing Xu; James M. Clark (2018). "Postcranial anatomy of Yinlong downsi (Dinosauria: Ceratopsia) from the Upper Jurassic Shishugou Formation of China and the phylogeny of basal ornithischians". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 16 (14): 1159–1187. doi:10.1080/14772019.2017.1369185. S2CID 90051025.

- ^ Novas, F., Agnolin, F., Rozadilla, S., Aranciaga-Rolando, A., Brissón-Eli, F., Motta, M., Cerroni, M., Ezcurra, M., Martinelli, A., D'Angelo, J., Álvarez-Herrera, G., Gentil, A., Bogan, S., Chimento, N., García-Marsà, J., Lo Coco, G., Miquel, S., Brito, F., Vera, E., Loinaze, V., Fernandez, M., & Salgado, L. (2019). Paleontological discoveries in the Chorrillo Formation (upper Campanian-lower Maastrichtian, Upper Cretaceous), Santa Cruz Province, Patagonia, Argentina. Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales, 21(2), 217-293.

- ^ Matthew G. Baron; David B. Norman; Paul M. Barrett (2016). "Postcranial anatomy of Lesothosaurus diagnosticus (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) from the Lower Jurassic of southern Africa: implications for basal ornithischian taxonomy and systematics". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. in press. doi:10.1111/zoj.12434

- ^ Canudo, José; Carballido, Jose; Garrido, Alberto; Salgado, Leonardo (2018). "A new rebbachisaurid sauropod from the Aptian–Albian, Lower Cretaceous Rayoso Formation, Neuquén, Argentina". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 63. doi:10.4202/app.00524.2018. ISSN 0567-7920.

- ^ José F. Bonaparte, Bernardo J. González Riga and Sebastián Apesteguía 2006. Ligabuesaurus leanzai gen. et sp. nov. (Dinosauria, Sauropoda), a new titanosaur from the Lohan Cura Formation (Aptian, Lower Cretaceous) of Neuquén, Patagonia, Argentina. Cretaceous Research 27(3): 364–376.

- ^ Gianechini, Federico A.; Méndez, Ariel H.; Filippi, Leonardo S.; Paulina-Carabajal, Ariana; Juárez-Valieri, Rubén D.; Garrido, Alberto C. (2021). "A New Furileusaurian Abelisaurid from La Invernada (Upper Cretaceous, Santonian, Bajo De La Carpa Formation), Northern Patagonia, Argentina". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 40 (6): e1877151. doi:10.1080/02724634.2020.1877151.

- ^ Becerra, M.C.; Pol, D.; Rauhut, O.W.M.; Cerda, I.A. (2016). "New heterodontosaurid remains from the Cañadón Asfalto Formation: cursoriality and the functional importance of the pes in small heterodontosaurids". Journal of Paleontology. 90 (3): 555–577. doi:10.1017/jpa.2016.24. S2CID 56436933.

- ^ González Riga, B.J. (2003). "A new titanosaur (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Mendoza, Argentina". Amehginiana 40: 155–172.

- ^ Rolando MA, Garcia Marsà JA, Agnolín FL, Motta MJ, Rodazilla S, Novas FE (2022). "The sauropod record of Salitral Ojo del Agua: An Upper Cretaceous (Allen Formation) fossiliferous locality from northern Patagonia, Argentina". Cretaceous Research. 129: 105029. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2021.105029. ISSN 0195-6671. S2CID 240577726.

- ^ Paulina-Carabajal, Ariana; Currie, Philip J. (2017). "The Braincase of the Theropod Dinosaur Murusraptor: Osteology, Neuroanatomy and Comments on the Paleobiological Implications of Certain Endocranial Features". Ameghiniana. 54 (5): 617–640. doi:10.5710/AMGH.25.03.2017.3062. S2CID 83814434.

- ^ Otero, Alejandro; Cuff, Andrew R.; Allen, Vivian; Sumner-Rooney, Lauren; Pol, Diego; Hutchinson, John R. (2019-05-20). "Ontogenetic changes in the body plan of the sauropodomorph dinosaur Mussaurus patagonicus reveal shifts of locomotor stance during growth". Scientific Reports. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. 9 (1): 7614. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.7614O. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-44037-1. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6527699. PMID 31110190.

- ^ Hartman, S.; Mortimer, M.; Wahl, W.R.; Lomax, D.R.; Lippincott, J.; Lovelace, D.M. (2019). "A new paravian dinosaur from the Late Jurassic of North America supports a late acquisition of avian flight". PeerJ. 7: e7247. doi:10.7717/peerj.7247. PMC 6626525. PMID 31333906.

- ^ Marsola, Júlio C. A.; Bittencourt, Jonathas S.; J. Butler, Richard; Da Rosa, Átila A. S.; Sayão, Juliana M.; Langer, Max C. (2019). "A new dinosaur with theropod affinities from the Late Triassic Santa Maria, South Brazil". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 38 (5): e1531878. doi:10.1080/02724634.2018.1531878. S2CID 91999370.

- ^ Pacheco, Cristian; Müller, Rodrigo T.; Langer, Max; Pretto, Flávio A.; Kerber, Leonardo; Dias da Silva, Sérgio (2019-11-08). "Gnathovorax cabreirai : a new early dinosaur and the origin and initial radiation of predatory dinosaurs". PeerJ. 7: e7963. doi:10.7717/peerj.7963. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 6844243. PMID 31720108.

- ^ José L. Carballido; Diego Pol; Mary L. Parra Ruge; Santiago Padilla Bernal; María E. Páramo-Fonseca; Fernando Etayo-Serna (2015). "A new Early Cretaceous brachiosaurid (Dinosauria, Neosauropoda) from northwestern Gondwana (Villa de Leyva, Colombia)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 35 (5): e980505. doi:10.1080/02724634.2015.980505. S2CID 129498917.

- ^ Philip D. Mannion, Ronan Allain & Olivier Moine, 2017, "The earliest known titanosauriform sauropod dinosaur and the evolution of Brachiosauridae", PeerJ 5: e3217

- ^ Holtz, Thomas R. (2012). "Holtz's Genus List" (PDF).

- ^ Salgado, L. (1996). "Pellegrinisaurus powelli nov. gen. et sp. (Sauropoda, Titanosauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous of Lago Pellegrini, Northwestern Patagonia, Argentina". Ameghiniana. 33 (4): 355–365. ISSN 1851-8044.

- ^ Rodolfo A. Coria; Guillermo J. Windholz; Francisco Ortega; Philip J. Currie (2018). "A new dicraeosaurid sauropod from the Lower Cretaceous (Mulichinco Formation, Valanginian, Neuquén Basin) of Argentina". Cretaceous Research. 93: 33–48. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2018.08.019. S2CID 135017018.

- ^ Martín D. Ezcurra (2017). "A new early coelophysoid neotheropod from the Late Triassic of northwestern Argentina". Ameghiniana. 54 (5): 506–538. doi:10.5710/AMGH.04.08.2017.3100. S2CID 135096489.

- ^ a b E. Martín Hechenleitner; Léa Leuzinger; Agustín G. Martinelli; Sebastián Rocher; Lucas E. Fiorelli; Jeremías R. A. Taborda; Leonardo Salgado (2020). "Two Late Cretaceous sauropods reveal titanosaurian dispersal across South America". Communications Biology. 3 (1): Article number 622. doi:10.1038/s42003-020-01338-w. PMC 7591563. PMID 33110212.

- ^ Grillo, O. N.; Delcourt, R. (2016). "Allometry and body length of abelisauroid theropods: Pycnonemosaurus nevesi is the new king". Cretaceous Research. 69: 71–89. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2016.09.001.

- ^ Hendrickx, Christophe; Bell, Phil R.; Pittman, Michael; Milner, Andrew R. C.; Cuesta, Elena; O'Connor, Jingmai; Loewen, Mark; Currie, Philip J.; Mateus, Octávio; Kaye, Thomas G.; Delcourt, Rafael (2022). "Morphology and distribution of scales, dermal ossifications, and other non-feather integumentary structures in non-avialan theropod dinosaurs". Biological Reviews. n/a (n/a). doi:10.1111/brv.12829. ISSN 1469-185X. PMID 34991180. S2CID 245820672.

- ^ Kellner, A. W. A. (1996). Fossilized theropod soft tissue. Nature 379, 32. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/379032a0

- ^ Langer, Max C.; Rincón, Ascanio D.; Ramezani, Jahandar; Solórzano, Andrés; Rauhut, Oliver W.M. (8 October 2014). "New dinosaur (Theropoda, stem-Averostra) from the earliest Jurassic of the La Quinta formation, Venezuelan Andes". Royal Society Open Science. Royal Society. 1 (2): 140–184. Bibcode:2014RSOS....140184L. doi:10.1098/rsos.140184. PMC 4448901. PMID 26064540.

- ^ Porfiri, Juan D; Juárez Valieri, Rubén D; Santos, Domenica D.D; Lamanna, Matthew C (2018). "A new megaraptoran theropod dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous Bajo de la Carpa Formation of northwestern Patagonia". Cretaceous Research. 89: 302–319. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2018.03.014. S2CID 134117648.

- ^ Carvalho, I.S.; Salgado, L.; Lindoso, R.M.; de Araújo-Júnior, H.I.; Costa Nogueir, F.C.; Soares, J.A. (2017). "A new basal titanosaur (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil" (PDF). Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 75: 74–84. Bibcode:2017JSAES..75...74C. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2017.01.010.

- ^ Poropat, S.F.; Nair, J.P.; Syme, C.E.; Mannion, P.D.; Upchurch, P.; Hocknull, S.A.; Cook, A.G.; Tischler, T.R.; Holland, T. (2017). "Reappraisal of Austrosaurus mckillopi Longman, 1933 from the Allaru Mudstone of Queensland, Australia's first named Cretaceous sauropod dinosaur" (PDF). Alcheringa. 41 (4): 543–580. doi:10.1080/03115518.2017.1334826. hdl:10044/1/48659. S2CID 134237391.

- ^ Gianechini, F. A.; Apesteguía, S. (2011). "Unenlagiinae revisited: Dromaeosaurid theropods from South America". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 83 (1): 163–95. doi:10.1590/S0001-37652011000100009. PMID 21437380.

- ^ R.D. Martínez and F.E. Novas, 2006, "Aniksosaurus darwini gen. et sp. nov., a new coelurosaurian theropod from the early Late Cretaceous of central Patagonia, Argentina", Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales, nuevo serie 8(2): 243-259

- ^ Matthew, Carrano (2012). "The phylogeny of Tetanurae (Dinosauria: Theropoda)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 10 (2): 211–300. doi:10.1080/14772019.2011.630927. S2CID 85354215.

- ^ Brum, Arthur Souza, Pêgas, Rodrigo Vargas, Bandeira, Kamila Luisa Nogueira, Souza, Lucy Gomes de, Campos, Diogenes de Almeida, & Kellner, Alexander Wilhelm Armin. (2021). A new Unenlagiinae (Theropoda: Dromaeosauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of Brazil. https://doi.org/10.1002/spp2.1375

- ^ Ezcurra, M.D. & Novas, F.E. 2005. Phylogenetic relationships of the Triassic theropod Zupaysaurus rougieri from NW Argentina. Presented in August 2005 during the II Latin American Congress of Vertebrate Paleontology Archived May 4, 2006, at the Wayback Machine in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. This analysis will be published in peer-reviewed print form later in 2006. A summary of the talk can be seen here.

Categories:

- Dinosaurs of South America

- Lists of dinosaurs by landmass

- Lists of animals of South America