Maryland, My Maryland

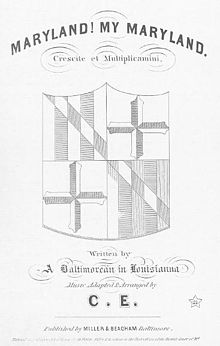

The original sheet music of "Maryland, My Maryland" | |

Regional anthem of | |

| Lyrics | James Ryder Randall, 1861 |

|---|---|

| Music | Melchior Franck, 1615 |

| Adopted | April 29, 1939 |

| Relinquished | May 18, 2021 |

| Succeeded by | None |

| Audio sample | |

"Maryland, My Maryland" (instrumental)

| |

"Maryland, My Maryland" was the state song of the U.S. state of Maryland from 1939 to 2021.[1] The song is set to the melody of "Lauriger Horatius"[2] — the same tune "O Tannenbaum" was taken from. The lyrics are from a nine-stanza poem written by James Ryder Randall (1839–1908) in 1861. The state's general assembly adopted "Maryland, My Maryland" as the state song on April 29, 1939.[3] After more than ten attempts to change the state song, over 40 years, on March 22, 2021, both houses of the General Assembly voted by substantial margins to abandon "Maryland, My Maryland" as the state song without a replacement. On May 18, 2021, Governor Larry Hogan signed the bill.[1][4]

The song's words refer to Maryland's history and geography and specifically mention several historical figures of importance to the state. The song calls for Marylanders to fight against the U.S. and was used across the Confederacy during the Civil War as a battle hymn.[5] It has been called America's "most martial poem".[6]

Due to its origin in reaction to the Baltimore riot of 1861 and Randall's support for the Confederate States, it includes lyrics that refer to President Abraham Lincoln as "the tyrant", "the despot", and "the Vandal", and to the Union as "Northern scum", as well as referring to the phrase "Sic semper tyrannis", which was the slogan later shouted by Marylander John Wilkes Booth when he assassinated Lincoln.[4][7] For these reasons, occasional attempts were made to replace it as Maryland's state song from the 1970s onward.[8] These attempts succeeded in 2021.[1][9]

History[]

The poem was a result of events at the beginning of the Civil War. During the secession crisis, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln (referred to in the poem as "the despot" and "the tyrant") ordered U.S. troops to be brought to Washington, D.C., to protect the capital and to prepare for war with the seceding southern states. Many of these troops were brought through Baltimore City, a major transportation hub. There was considerable Confederate sympathy in Maryland at the time, as well as a large number of residents who objected to waging a war against their southern neighbors.[10] Riots ensued as Union troops came through Baltimore on their way south in April 1861 and were attacked by mobs. A number of Union troops and Baltimore residents were killed in the Baltimore riots. The Maryland legislature summarized the state's ambivalent feelings when it met soon after, on April 29, voting 53–13 against secession,[11][12] but also voting not to reopen rail links with the North, and requesting that Lincoln remove the growing numbers of federal troops in Maryland.[10] At this time the legislature seems to have wanted to avoid involvement in a war against its seceding neighbors.[10] The contentious issue of troop transport through Maryland would lead one month later to the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, also a Marylander, penning one of the United States' most controversial wartime rulings, Ex parte Merryman.[13]

One of the reported victims of these troop transport riots was Francis X. Ward, a friend of James Ryder Randall. Randall, a native Marylander, was teaching at Poydras College in Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana, at the time and, moved by the news of his friend's death, wrote the nine-stanza poem, "Maryland, My Maryland". The poem was a plea to his home state of Maryland to secede from the Union and join the Confederacy.[4] Randall later claimed the poem was written "almost involuntarily" in the middle of the night on April 26, 1861. Being unable to sleep after hearing the news, he claimed "some powerful spirit appeared to possess me ... the whole poem was dashed off rapidly ... [under] what may be called a conflagration of the senses, if not an inspiration of the intellect".[14]

The poem contains many references to the Revolutionary War as well as to the Mexican–American War and Maryland figures in that war (many of whom have fallen into obscurity). It was first published in the New Orleans Sunday Delta. The poem was quickly turned into a song — put to the tune of "Lauriger Horatius" — by Baltimore resident Jennie Cary, sister of Hetty Cary.[15] It became instantly popular in Maryland, aided by a series of unpopular federal actions there, and throughout the South. It was sometimes called "the Marseillaise of the South". Confederate States Army bands played the song after they crossed into Maryland territory during the Maryland Campaign in 1862.[16] By 1864, the Southern Punch noted the song was "decidedly most popular" among the "claimants of a national song" for the Confederacy.[17] According to some accounts, General Robert E. Lee ordered his troops to sing "Maryland, My Maryland", as they entered the town of Frederick, Maryland, but his troops received a cold response, as Frederick was located in the unionist western portion of the state.[18] At least one Confederate regimental band also played the song as Lee's troops retreated back across the Potomac after the bloody Battle of Antietam.

During the War, a version of the song was written with lyrics that supported the U.S. cause.[19][20]

After the War, author Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. compared "Maryland, My Maryland" with "John Brown's Body" as the two most popular songs from the opposing sides in the early months of the conflict. Each side, he wrote, had "a sword in its hand, each with a song in its mouth". The songs indicated as well their respective audiences, according to Holmes: "One is a hymn, with ghostly imagery and anthem-like ascription. The other is a lyric poem, appealing chiefly to local pride and passion."[14]

Lyrics[]

I

The despot's heel is on thy shore,

Maryland![a]

His torch is at thy temple door,

Maryland!

Avenge the patriotic gore

That flecked the streets of Baltimore,

And be the battle queen of yore,

Maryland! My Maryland!

II

Hark to an exiled son's appeal,

Maryland!

My mother State! to thee I kneel,

Maryland!

For life and death, for woe and weal,

Thy peerless chivalry reveal,

And gird thy beauteous limbs with steel,

Maryland! My Maryland!

III

Thou wilt not cower in the dust,

Maryland!

Thy beaming sword shall never rust,

Maryland!

Remember Carroll's sacred trust,

Remember Howard's warlike thrust,—

And all thy slumberers with the just,

Maryland! My Maryland!

IV

Come! 'tis the red dawn of the day,

Maryland!

Come with thy panoplied array,

Maryland!

With Ringgold's spirit for the fray,

With Watson's blood at Monterey,

With fearless Lowe and dashing May,

Maryland! My Maryland!

V

Come! for thy shield is bright and strong,

Maryland!

Come! for thy dalliance does thee wrong,

Maryland!

Come to thine own anointed throng,

Stalking with Liberty along,

And sing thy dauntless slogan song,

Maryland! My Maryland!

VI

Dear Mother! burst the tyrant's chain,

Maryland!

Virginia should not call in vain,

Maryland!

She meets her sisters on the plain—

"Sic semper!" 'tis the proud refrain

That baffles minions back amain,

Maryland! My Maryland!

VII

I see the blush upon thy cheek,

Maryland!

For thou wast ever bravely meek,

Maryland!

But lo! there surges forth a shriek,

From hill to hill, from creek to creek—

Potomac calls to Chesapeake,

Maryland! My Maryland!

VIII

Thou wilt not yield the Vandal toll,

Maryland!

Thou wilt not crook to his control,

Maryland!

Better the fire upon thee roll,

Better the blade, the shot, the bowl,

Than crucifixion of the soul,

Maryland! My Maryland!

IX

I hear the distant thunder-hum,

Maryland!

The Old Line's bugle, fife, and drum,

Maryland!

She is not dead, nor deaf, nor dumb—

Huzza! she spurns the Northern scum!

She breathes! she burns! she'll come! she'll come!

Maryland! My Maryland!

- ^ Although the words as written, and as adopted by statute, contain only one instance of "Maryland" in the second and fourth line of each stanza, common practice is to sing "Maryland, my Maryland" each time to keep with the meter of the tune.

Efforts to repeal, replace, or revise Maryland's state song[]

Unsuccessful efforts to revise the lyrics to the song or to repeal or replace the song altogether were attempted by members of the Maryland General Assembly in 1974, 1980, 1984, 2001, 2002, 2009, 2016, 2018, and 2019.[21][22][23]

In July 2015, Delegate Peter A. Hammen, chairman of the Maryland House of Delegates House Health and Government Operations Committee, asked the Maryland State Archives to form an advisory panel to review the song. The panel issued a report in December 2015, that suggested that it was time the song was retired. The panel offered several options for revising the song's lyrics or replacing it with another song altogether.[24]

The panel report stated that the Maryland state song should:

- celebrate Maryland and its citizens;

- be unique to Maryland;

- be historically significant;

- be inclusive of all Marylanders;

- be memorable, popular, singable and short (one, or at the most, two stanzas long)[25]

In 2016, the Maryland Senate passed a bill to revise the song to include just the third verse of Randall's lyrics and only the fourth verse of a poem of the same name, written in 1894, by John T. White.[26][27] This revision had the support of Maryland Senate President Thomas V. "Mike" Miller, who resisted any changes to "Maryland, My Maryland" in the past.[28][29] It was not reported out of the Health and Government Operations Committee in the House of Delegates, however.[30]

On August 28, 2017, The Mighty Sound of Maryland, the marching band of the University of Maryland, announced that they would suspend playing the song until they had time to review if it was aligned with the values of the school.[31]

On March 16, 2018, the Maryland Senate passed an amended bill that would have changed the status of "Maryland! My Maryland!" from the "official State song" to the "Historical State song".[32] The bill received an Unfavorable Report by the House Health and Government Operations Committee on April 9, 2018.[33]

A bill was filed in the House of Delegates for the 2020 session to appoint an advisory panel to "review public submissions and suggestions for a new State song", but the bill did not advance past the hearing because the General Assembly adjourned early due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[34][35][36]

On March 29, 2021, a bill to remove "Maryland, My Maryland" as the state song (with no replacement) passed the Maryland legislature.[37] Governor Larry Hogan signed the bill into law on May 18, 2021.[1][4]

Other uses of the melody[]

The songs "Michigan, My Michigan", "Florida, My Florida", and "The Song of Iowa"[38] are set to the same tune as "Maryland, My Maryland".[39] The College of the Holy Cross[40] and St. Bonaventure University[41] both use the tune for their respective alma maters.

In the film version of Gone with the Wind, "Maryland, My Maryland" is played at the opening scene of the Charity Ball when Scarlett and Melanie are reacquainted with Rhett Butler. Kid Ory's Creole Jazz Band recorded an instrumental version of "Maryland, My Maryland" on September 8, 1945, in the New Orleans jazz revival.[42] Bing Crosby included the song in a medley on his album 101 Gang Songs (1961). In 1962, Edmund Wilson used the phrase "patriotic gore" from the song as the title of his book on the literature of the Civil War.[43]

The third verse of "Maryland, My Maryland" was sung annually at the Preakness Stakes by the United States Naval Academy glee club;[44] that practice was discontinued in 2020.[45][46]

See also[]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "On bill-signing day, Hogan officially legalizes sports betting, repeals state song". WJLA-TV. Associated Press. May 18, 2021. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- ^ Code of Maryland, State Government, Title 13, § 13-307.

- ^ Maryland State Archives (2004). Maryland State Song – "Maryland, My Maryland". Retrieved 27 Dec. 2004.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Maryland state song, which refers to Lincoln as "tyrant" and urges secession, is repealed". CBS News. May 20, 2021. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- ^ Catton, Bruce. The Coming Fury [1961]. p. 352.

- ^ Randall, James Ryder. 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia, p. 639.

- ^ Booth, John Wilkes. "Diary Entry of John Wilkes Booth". Archived from the original on 2010-12-29. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ^ Another Try for Maryland's State Song?, The Washington Post, April 6, 2000.

- ^ Wood, Pamela (March 18, 2021). "Maryland's pro-Confederate state song is close to being ditched, after repeated tries". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

The House... approved the state song repeal.... [A] Senate committee took a unanimous, bipartisan vote for repeal.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Teaching American History in Maryland – Documents for the Classroom: Arrest of the Maryland Legislature, 1861". Maryland State Archives. 2005. Archived from the original on January 11, 2008. Retrieved February 6, 2008.

- ^ Mitchell, p.87

- ^ "States Which Seceded". eHistory. Civil War Articles. Ohio State University. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ McGinty (2011) p. 173. "The decision was controversial on the day it was announced, and it has remained controversial ever since." Neely (2011) p. 65 Quoting Lincoln biographer James G. Randall,"Perhaps no other feature of Union policy was more widely criticized nor more strenuously defended."

- ^ Jump up to: a b Alice Fahs. The Imagined Civil War: Popular Literature of the North and South, 1861–1865. The University of North Carolina Press, 2001: 80. ISBN 0-8078-2581-6

- ^ Mrs. Burton Harrison (1911). Recollections Grave and Gay. Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 57.

- ^ Scharf, J. Thomas (1967). History of Maryland From the Earliest Period to the Present Day. 3. Hatboro, PA: Tradition Press. p. 494.

- ^ Alice Fahs. The Imagined Civil War: Popular Literature of the North and South, 1861–1865. The University of North Carolina Press, 2001: 79–80. ISBN 0-8078-2581-6

- ^ See James M. MacPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (Oxford University Press, 1988), 535-36, Amazon Kindle Location 11129-45.

- ^ Shade, Colette. "When a State Song Is a Confederate Battle Cry", The New Republic, New York, February 29, 2016, retrieved on September 4, 2017.

- ^ University Libraries. "Women, War, and Song", University of Maryland, Maryland, retrieved on September 4, 2017.

- ^ Gaines, Danielle E.. "Political Notes: State song legislation on the horizon and a history of Winchester Hall", Frederick News-Post, Frederick, 31 August 2017. Retrieved on 04 September 2017.

- ^ Donovan, Doug, and Fishel, Ellen. "The debate over Maryland's state song is a familiar refrain", The Baltimore Sun, Baltimore, 15 March 2018. Retrieved on 11 April 2018.

- ^ Gaines, Danielle E.. "House Committee Again Considering State Song Repeal", Maryland Matters, Takoma Park, 13 March 2019. Retrieved on 08 April 2019.

- ^ Wheeler, Timothy B. "Maryland, My Maryland? Panel urges changes in state song", The Baltimore Sun, Baltimore, 17 December 2015. Retrieved on 16 April 2016.

- ^ Gaines, Danielle E.. "Advisory group recommends retirement of Maryland's state song", The Frederick News-Post, Frederick, 16 December 2015. Retrieved on 16 April 2016.

- ^ Wood, Pamala. "Revised state song moves forward in Annapolis", Baltimore Sun, Baltimore, 15 March 2017. Retrieved on 04 September 2017.

- ^ Maryland House bill 1241 (pdf)

- ^ Gaines, Danielle E. "Committee hearing on state song attracts impromptu sing-alongs", The Frederick News-Post, Frederick, 10 February 2016. Retrieved on 07 September 2017.

- ^ Wood, Pamela (August 29, 2017). "University of Maryland band nixes Confederate state song, could lawmakers be next?". The Baltimore Sun. pp. 1 and 9.

- ^ Associated Press. "Move stalls change to Maryland state song from Civil War era", WRC-TV, Washington, D. C., 31 March 2016. Retrieved on 07 September 2017.

- ^ Associated Press. "UMD Band Stops Playing pro-Confederate Song", Afro, Baltimore, 30 August 2017. Retrieved on 04 September 2017.

- ^ Dance, Scott, and Dresser, Michael. "Senators pass bill stripping "Maryland, My Maryland" of official status", The Baltimore Sun, Baltimore, 16 March 2018. Retrieved on 11 April 2018.

- ^ Maryland General Assembly

- ^ Women's Democratic Club. "WDC Takes a Stand – Retire Our Confederate State Song This Session!", "WDC, Montgomery County, 18, March 2020. Retrieved on 11 April 2020.

- ^ Maryland House bill 0181 (pdf)

- ^ Collins, David. "Maryland General Assembly adjourns early due to coronavirus", "WBAL, Baltimore, 18, March 2020. Retrieved on 11 April 2020.

- ^ Vigdor, Neil (2021-03-30). "Maryland's State Song, a Nod to the Confederacy, Nears Repeal". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-04-19.

- ^ "State Symbols and Song". Iowa Official Register. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- ^ Baltimore Sun.. "Maryland, my meh song", The Baltimore Sun, Baltimore, 15 March 2016. Retrieved on 04 September 2017.

- ^ Letter from the President of the General Alumni Association Holy Cross Magazine

- ^ "St. Bonaventure website". Archived from the original on 2011-06-01. Retrieved 2018-12-19.

- ^ Stuart Nicholson (1 January 2000). Essential Jazz Records: Volume 1: Ragtime to Swing. A&C Black. pp. 52–53. ISBN 978-0-7201-1708-0.

- ^ Wilson, Edmund. (1962). Patriotic Gore: Studies in the Literature of the American Civil War. New York: Farrar Straus & Giroux. Republished in 1994 by W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-31256-9 / ISBN 978-0-393-31256-0.

- ^ Shastry, Anjali. "Maryland the latest target in nationwide Confederate cleansing", The Washington Times, Washington, D. C., 21 January 2016. Retrieved on 31 March 2017.

- ^ Vespe, Frank (September 10, 2020). "Preakness: No More 'Maryland, My Maryland'". bloodhorse.com. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ Ginsburg, David (October 3, 2020). "Preakness 2020: No fans, no traffic, no booze, no May heat". AP. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- Maryland State Archives (2004). Maryland State Song – "Maryland, My Maryland". Retrieved 27 Dec. 2004.

- The Morrison Foundation for Musical Research, Inc. (15 Jan. 2004). James Ryder Randall (1839–1908). Retrieved 27 Dec. 2004.

External links[]

- Music of Maryland

- United States state songs

- Songs of the American Civil War

- Maryland in the American Civil War

- Preakness Stakes

- Songs based on American history

- Songs based on poems

- Music controversies