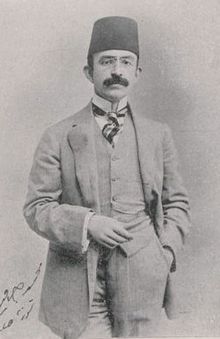

Mehmet Cavit Bey

Mehmet Cavit | |

|---|---|

| |

| Minister of Finance | |

| In office July 1909 – October 1911 | |

| Monarch | Mehmed V |

| Preceded by | Mehmed Rifat Bey |

| Succeeded by | Mustafa Nail Bey |

| In office March 1914 – November 1914 | |

| Monarch | Mehmed V |

| Preceded by | Abdurrahman Vefik Sayın |

| Succeeded by | Talaat Pasha |

| Member of the Chamber of Deputies | |

| Constituency | Selanik (1908, 1912) Kale-i Sultaniye (1914) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1875 Salonica, Salonica Vilayet, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 26 August 1926 (aged 50–51) Ankara, Turkey |

| Occupation | Politician, economist, newspaper editor |

Mehmet Cavit Bey, Mehmed Cavid Bey or Mehmed Djavid Bey (1875 – 26 August 1926) was an Ottoman economist, newspaper editor and leading politician during the dissolution period of the Ottoman Empire. A founding member of the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), he was part of the Young Turks and had positions in government after the constitution was re-established. In the beginning of the Republican period, he was executed for alleged involvement in an assassination attempt against Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.[1]

Early years and career[]

Cavit was born in the Salonica Vilayet of the Ottoman Empire (modern day Thessaloniki). His father was Naim, a merchant, and his mother was Pakize; they were cousins. His family had links to followers of Sabbatai Zevi,[2][3][4] and he was a Dönme.[5] He spoke Greek and French, attending the progressive Şemsi Efendi School, the same school as Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. He attended Mülkiye academy in Istanbul for civil servants, and upon graduation he secured employment with a state bank, and at the same time taught economics and worked within the Ministry of Education.[6]

Cavit was more successful than the average state employee in Istanbul, but for unknown reasons he decided to leave his budding career and move back to Salonica. As fears of collapse grew in Salonica amidst the spreading insurrections and violence of the Balkans and the autocratic rule and inaction of Abdülhamid II, foreign influence over the Ottoman state also grew (along with the nation's debt). Cavid and other supporters of the Ottoman nation came to believe that the sultan had to step aside for the good of the empire. This core group founded the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), called the Young Turks by foreign press.[7]

After the proclamation of the Second Constitution in 1908, he was elected deputy of Salonica and Kale-i Sultaniye (Çanakkale) into the parliament in Constantinople. Following the 31 March Incident in 1909, Cavit Bey was appointed minister of finance in the cabinet of Grand Vizier Tevfik Pasha. In the aftermath of the Savior Officer insurrection and repression of the CUP, Cavit hid in a French battleship and escaped to Marseilles.[8] Cavit would regain his position in the wake of Grand Vizier Mahmud Şevket Pasha's assassination.

Following the orchestrated Black Sea Raid on Russian ports in 1914, Cavit resigned. For the next few weeks, central committee brother Dr. Mehmed Nazım himself also a Dönme would bully Cavit for being a "treacherous Jew".[5] He remained an influential figure in the Empire's dealings with Germany until he returned to his post in February 1917.[9] Up to the Armistice of Mudros in 1918 following the World War I, Cavit Bey played an important role in the CUP. Cavit Bey represented the Ottoman Empire in postwar financial negotiations in London and Berlin.

During World War I, Cavid was not fully trusted by the CUP leadership. He did not find out about the Armenian genocide until August 1915, and condemned it in his diary, writing "Ottoman history has never opened its pages, even during the time of the Middle Ages, onto such determined murder[s] and large scale cruelty."[10]

If you want to bloody the Armenian question politically, then you scatter the people in the Armenian provinces, but scatter them in a humane manner. Hang the traitors, even if there are thousands of them. Who would entertain hiding Russians [and] the supporters of Russians? But stop right there. You dared to annihilate the existence of an entire nation, not [only] their political existence. You are both iniquitous and incapable. What kind of conscience must you have to [be able to] accept the drowning, in the mountains and next to lakes, of those women, children and the elderly who were taken to the countryside![10]

He lamented, "With these acts we have [ruined] everything. We put an irremovable stain on the current administration."[10]

Republican period[]

In 1921, Mehmet Cavit Bey married Nazlıyar Hanım, the divorced wife of Şehzade Mehmed Burhaneddin. In 1924, their son Osman Şiar was born. After Cavit Bey's execution, his son was raised by his close friend Hüseyin Cahit Yalçın. Following the enactment of the Surname Law in 1934, Osman Şiar adopted the surname Yalçın.[11]

In the early period of the Republican era, Mehmet Cavit Bey was charged with involvement in the assassination attempt in Izmir against Mustafa Kemal Pasha. After a widespread government investigation, Cavit Bey was convicted and later executed by hanging on August 26, 1926 in Ankara.[12] Thirteen others, including other CUP members and , were found guilty of treason and hanged.[13]

The letters which Cavit Bey wrote to his wife Aliye Nazlı during his imprisonment were given to her only after his execution. She had the letters published later as a book entitled, Zindandan Mektuplar ("Letters from the Dungeon").[14]

In 1950, Cavit Bey's remains were transferred and reinterred at the Cebeci Asri Cemetery in Ankara.[11]

Bibliography[]

- Zindandan Mektuplar (2005) Liberte Yayınları, 212 pp. ISBN 9789756877913

- Kieser, Hans-Lukas (26 June 2018), Talaat Pasha: Father of Modern Turkey, Architect of Genocide, Princeton University Press (published 2018), ISBN 978-0-691-15762-7

References[]

- ^ Andrew Mango, Atatürk, PUBLISHER?, 1999, pp. 448-453

- ^ Ilgaz Zorlu, Evet, Ben Selânikliyim: Türkiye Sabetaycılığı, Belge Yayınları, 1999, p. 223.

- ^ Yusuf Besalel, Osmanlı ve Türk Yahudileri, Gözlem Kitabevi, 1999, p. 210.

- ^ , Musa'nın Evlatları, Cumhuriyet'in Yurttaşları, İletişim Yayınları, 2001, p. 54.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kieser 2018, p. 215.

- ^ Dawn: Turkey in the Age of Atatürk by Ryan Gingeras

- ^ Dawn: Turkey in the Age of Atatürk by Ryan Gingeras

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 130.

- ^ Kent, Marian (2005). The Great Powers and the End of the Ottoman Empire. Routledge. ISBN 9781135777999.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Ozavci, Ozan (2019). "Honour and Shame: The Diaries of a Unionist and the 'Armenian Question'.". In Kieser, Hans-Lukas; Anderson, Margaret Lavinia; Bayraktar, Seyhan; Schmutz, Thomas (eds.). The End of the Ottomans: The Genocide of 1915 and the Politics of Turkish Nationalism. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 212–214. ISBN 978-1-78672-598-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Nazif Özge ve Gerçel Ailesi - Rüştü Karakaşlı" (in Turkish). SosyalistKültür. 2008-07-05. Archived from the original on July 7, 2009. Retrieved 2009-07-14.

- ^ "Mehmet Cavit Bey" (in Turkish). 2008-12-15. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved 2009-07-14.

- ^ Touraj Atabaki, Erik Jan Zürcher, 2004, Men of Order: Authoritarian Modernization under Ataturk and Reza Shah, I.B.Tauris, ISBN 1860644260, page 207

- ^ "Zindandan Mektuplar" (in Turkish). KitapTürk. Retrieved 2009-07-14.

- 1875 births

- 1926 deaths

- Writers from Thessaloniki

- People from Salonica Vilayet

- Turkish non-fiction writers

- Turkish economists

- Turkish newspaper editors

- Government ministers of the Ottoman Empire

- Burials at Cebeci Asri Cemetery

- Committee of Union and Progress politicians

- People executed by Turkey by hanging

- 20th-century executions for treason

- People executed for treason against Turkey

- Turkish people of Jewish descent

- Politicians from Thessaloniki