Mer (community)

મેર, મહેર | |

|---|---|

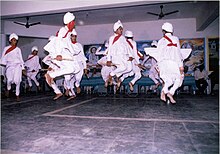

Mer Rās | |

| Total population | |

| 250,000 (1980) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Porbandar district, Junagadh district, Devbhumi Dwarka district, Jamnagar district | |

| Languages | |

| Gujarati | |

| Religion | |

| Hinduism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Gujarati people |

Mer, Maher or Mehr, (Gujarati: ISO 15919: Mēr, Mahēr or Mēhr) is a kshatriya jāti from the Saurashtra region of Gujarat in India.[1] They are largely based in the Porbandar district, comprising the low-lying, wetland Ghēḍ and highland Barḍā areas, and they speak a dialect of the Gujarati language.[2][3][4] The Mers of the Ghēḍ and Barḍā form two groups of the jāti and together they are the main cultivators in the Porbandar District.[5] Historically, the men served the Porbandar State as a feudal militia, led by Mer leaders.[6][7] In the 1881 Gazette of the Bombay Presidency, the Mers were recorded numbering at 23,850.[8] The 1951 Indian Census recorded 50,000 Mers.[9] As of 1980 there were estimated to be around 250,000 Mers.[10]

Origin[]

Mers of other lineages consider the Kēshwaḷā as the earliest lineage citing the proverb: Ādya Mēr Kēshwaḷā, jēni suraj purē chē śakh - "the sun stands testimony to the fact that Kēshwaḷās are the original Mers." [11] An origin myth of the Kēshwaḷās descending from the neck hair of Rama was recorded by colonial authors.[7] However, possibly the oldest reference to Kēshwaḷās indicates that the founder of this lineage may have lived over a thousand years ago, although, this relies on the genealogies of Barots which are not considered completely accurate as they are projected back in time to pseudo-history.[12]

History[]

Mers were once associated with the Maitraka dynasty.[13][14] Sinha suggests that the word Maitraka is an adaption from Mihir, which is in turn an adaption from Mer and does not rule out the possibility that the ruling families of the Maitrakas originated from the Mers.[15] The kin of those slain in action were paid 100 rupees (£10) by the Rana during the late 1800s.[7] Mers did not pay rent on their land, only paying a hearth tax and if they cultivated, a plough tax in addition to sukhḍi (quit rent) on villages assigned to them.[7] Historically, highland Mers, also known as Bhōmiyā (landed) held more political power than lowland Mers with the latter being restricted from buying land from Bhōmiyās between 1884 and 1947.[16]

In the 1970s Sarman Munja Jadeja rose to prominence after killing gangsters Devu and Karsan Vagher who had been hired by Nanji Kalidas Mehta to break the strike at the Maharana Mills.[17] As the leader of organised crime in Porbandar he ran a parallel system of justice and was hailed by many Mers as a Robin Hood-like figure.[18] After killing 47 people, he renounced violence having been influenced by the Swadhyay Movement.[17] In 1986 he was murdered by a rival gang resulting in Santokben Jadeja taking over her husbands gang and killing 30 people to take revenge.[17] By the 1990s her gang was wanted in 500 cases and she in 9. Shantokben died in 2011, following which a rival ganglord, Bhima Dula Odedara became dominant in local crime and politics.[19] Odedara took control of the profitable limestone, chalk and bauxite mines; he was given double life imprisonment by the Gujarat High Court for double murder in 2017.[18][20]

Mers in politics[]

Mers have dominated the politics of the Kutiyana Vidhan Sabha, the Porbandar Vidhan Sabha and the Porbandar Lok Sabha seats.

The first Mer to become the MLA for Kutiyana was Indian National Congress member Maldevji Odedra in 1962; who also became the Gujarat Congress President. 1980 saw Congress candidate Vijaydasji Mahant elected and he retained his seat in 1985. Mahant also became the Gujarat Congress President.[21] In 1990 Santokben Jadeja won the Kutiyana assembly seat as a Janata Dal candidate. In 1995 her brother-in-law Bhura Munja Jadeja became the MLA for Kutiyana contesting as an independent. After the Jadejas, the Bharatiya Janata Party candidate Karsan Dula Odedara held the Kutiyana seat winning in 1999, 2002 and 2007. Since 2012 it has been held by Kandhal Jadeja a Nationalist Congress Party MLA and son of Santokben, who won again in 2017.[22]

Maldevji Odedra was elected from the Porbandar Vidhan Sabha seat in 1972 as an INC candidate. In 1985, Laxmanbhai Agath (INC) was elected. Babubhai Bokhiria (BJP) held the seat in 1995 and 1998, losing to Congress candidate Arjunbhai Modhwadiya in 2002. Modhwadiya maintained his seat in 2007 and became the Gujarat Congress President, but lost to Babubhai Bokhiria, who currently is the MLA for Porbandar, in 2012 and 2017.[21][22]

Maldevji Odedra held the Porbandar Lok Sabha seat in 1980 on behalf of INC. His son, Bharatbhai Odedra (INC) was elected in 1984 from Porbandar to the Lok Sabha.

Clans[]

The community is endogamous, that is, marriages take place within the community, but exogamous with respect to clan. That is the bride and groom belong to different clans (gotra) known as Bhāyāt. Genealogies of Mer families are maintained by Barots through name recording ceremonies.[23] Mers consist of 14 clans called Śakh which are further split into segments called Pankhī:[2][24]

- Bhaṭṭi

- Chauhāṇ

- Chavḍa

- Chūḍāsamā

- Jāḍējā

- Kēshwaḷā

- Ōḍēdarā

- Parmār

- Rājshākhā

- Sīsodiyā

- Sōlaṁkī

- Vāḍhēr

- Vaghēlā

- Vāḷā

Society and culture[]

Historically, Mers were wedded through arranged marriages, which were agreed between the parents of two new-borns. However, a girl married as a child would only be sent to live with her husband's family after achieving maturity.[25] Cross-cousin marriage was common, while polygamous marriages were rare, only being permitted if a man was unable to have children with his first wife.[25] The women of this community do not observe female seclusion norms and widow remarriage was not prohibited.[23] Dowry operates largely in the favour of women.[25] Differing from typical Hindu weddings, the Khaṁḍūṁ ceremony involves a sword being wed as a proxy for the groom. Grooms wear a jūmaṇuṁ made of twenty tolas of gold which has either been passed down or borrowed from relatives.[26] Modern transport and equipment such as orchestra troupes are employed.[26] Dates would be distributed in a custome called Lāṇ, to fellow villagers to celebrate a wedding or the birth of a son.[27]

Mers commission three types of Paliyas to venerate there ancestors. The first type is for surāpurā (lit. perfect brave, referring to warriors); the second for surdhan for ancestors who have died an unnatural death and finally for satis. They are venerated with sindoor by Mer descendants on Diwali.[28][29]

Mēr nō Rās (Dance of the Mer) a unique form of dandiya raas is performed. The performance includes liberal dusting of Gulal (vermillion) on the bodies and costumes of the dancers.[30] Mer men used to wear umbrella shaped gold earrings called Śiṁśorīya; while Mer women wore bead shaped Vedla. Mer women also tattooed large parts of their body including the neck, arms and legs.[31][32] Mer women were usually tattooed when they were about seven or eight years old. The hands and feet are marked first and then the neck and breast. It is customary for a girl to be tattooed before marriage.[33] A Mer proverb states 'We may be deprived of all things of this world but nobody has the power to remove the tattoo marks".[34] Mer tattoo motifs have a close relation to secular and religious subjects of devotion. Designs include holy men, feet of Rama or Lakshmi, women carrying water in pitchers on their head, Shravancarrying his parents on a lath (kāvad) to centers of pilgrimage, and popular gods like Rama, Krishna and Hanuman are also depicted. The lion, tiger, horse, camel, peacock, scorpion, bee and fly are other favorites.[35]

Mers are mostly vegetarian, with pearl millet (Bājarō), sorghum (Jōwār) and wheat rotis being consumed with vegetables, chillis and curds.[8] During weddings jaggery, ghee, lāpsi and khichdi is served.[36] As of 1976, it has been reported that vices are common amongst Mers with around 30% consuming alcohol despite the prohibition in Gujarat.[36] A 1980 study of the Mers estimated that: an average Mer household contains 6 people, 35% were literate, 95% of households owned their homes and 77% of household members were employed. 77% of those employed worked in the agricultural sector.[37] Small scale plant-based industries are run by Mers, including bio-diesel production from the Mōgali āranḍ (Jatropha curcus L), herbal shampoo from Aloe and ground nut, sesame and castor oil extracting mills.[36]

Historically Mers were considered Kshatriyas. However, in the local caste system, Vaishyas would not consume food from Mers due to their hygiene and their consumption of meat and alcohol.[38] Mers were considered part of the Kānṭio Varna or haughty groups that included other tribes such as Rajputs and Ahirs.[39] The Tēr Tāṁsḷī (13 bell-metal bowls) a group of thirteen communities that dine together but do not intermarry, includes the Mers.[40] In 1993 the Mandal Commission classified the Mers as an Other Backward Class.[41]

Religion[]

Beliefs and practices[]

Mers are Hindus and practise a variety of religious traditions ranging from Folk Hinduism to Yogic and Bhakti practises. In addition, each lineage also has a lineage deity or Kuldevi, referred to as Āī (grand-mother) who is worshipped by lighting a lamp in front of the murti.[42] While Mers worship all gods of the Hindu pantheon, devotion to Ramdevji and Vachhara Dada is a unique hallmark of Mer religious belief. Mer men and women maintain complete freedom in choosing their belief system and no member of a family forces another to follow their denomination.[43] Mer men are expected to have a guru to provide personal religious advice; those without one are disparagingly called nagūrū (without a guru).[44]

The worship of Ramdev Pir is also formalised through a panth focusing on the worship of jyot and the secret Pāt ceremony is organised, breaking all caste and societal barriers.[45] The Mers of Ghēḍ organise the Manḍap ceremony with Kolis and bring entire villages together in worship.[46] Bhakti tradition is practised through the singing of bhajans about the Hindu epics; jiva; brahman; jnana; sannyasa; bhakti and moksha.[47][48] Vaishnavism, Shaivism and Shaktism are found amongst the Mers, with every village containing a temple to Shiva, Rama, and various forms of Devi. Amidst the worshippers of Devi, the presence of a small minority of secret Vamachara practitioners has also been noted; they are reputed to worship Kali with meat and alcohol.[45] Within the Bhakti tradition the Pranami Sampraday is prevalent and devotees worship Krishna as Gopis.[49] The Kabir panth also has a small following, functioning in open ceremonies under the guidance of a mahant.[50] Some Mers follow Pirs based on individual experiences.[51] Typical forms of Hindu worship such as aarti are common. Satis of the Charan jāti including Khodiyar are highly revered.[52][53] When praying to Kuldevis, Satis or Vachhara Dada, the services of a bhuvā (shaman) are employed.[53] Around marriage the goddess Randal is worshipped for fertility, while Brahmins are invited to recite the Satyanarayan Katha to pray for relief from difficult times.

Festivals and pilgrimages[]

Melas are fairs organised on religious occasions but also have secular aspects. The largest fair of the Mer region is the Porbandar Mela. The Mer community annually celebrates 'Rukmini no Choro', at the beautiful Madhavrai Temple. It is believed that Krishna married Rukmini in Madhavpur.[54] Mers also attend regional fairs such as the Maha Shivratri Mela in Bhavnath, Junagadh and the mela at the Bileshwar Mahadev Temple in the Barda Hills.[55] On Bhim Agyaras other fairs are organised in Odadar and Visavada in the highland and Balej in the low-land.[56] Mers go on pilgrimage to Dwarka. Another common pilgrimage is to Mount Girnar.[57]

Diaspora[]

Mers started migrating to the British colonies in East Africa during early parts of 20th century. The businessman, Nanji Kalidas Mehta was instrumental in helping them to migrate to Africa. Many of the early migrants were from the highlands villages.[58] Following the expulsion of Asians from Uganda many Mers settled in Britain and other Western countries.[59]

Notable people[]

Sports[]

Sonia Odedra - English female Cricketer Jayesh Odedra - Indian Cricketer Jay Odedra -omani cricketer

Politics[]

- Babubhai Bokhiria ([60]

- Arjun Modhwadia (1953-) [60]

- Santokben Jadeja (-2011) [61]

- Kandhal Jadeja - Son of Santokhben and member of Gujarat legislative assembly [60]

References[]

- ^ Trivedi 1961, p. 1, 14, 40. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTrivedi1961 (help)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Franco 2004, p. 242.

- ^ Trivedi 1986, p. viii. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTrivedi1986 (help)

- ^ Trivedi 1961, p. 1-3. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTrivedi1961 (help)

- ^ Trivedi 1961, p. 100-103. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTrivedi1961 (help)

- ^ Maddock 1993, p. 104.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Campbell 1881, p. 138.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Campbell 1881, p. 139.

- ^ Trivedi 1999, p. 1.

- ^ Trivedi 1999, p. 9.

- ^ Trivedi 1961, p. 106. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTrivedi1961 (help)

- ^ Trivedi 1961, p. 107-108. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTrivedi1961 (help)

- ^ Fernando Franco; Jyotsna Macwan; Suguna Ramanathan (1 February 2004). Journeys to Freedom: Dalit Narratives. Popular Prakashan. pp. 242–. ISBN 978-81-85604-65-7. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ Odedra, N. K. (2009). Ethnobotany of Maher tribe in Porbandar district, Gujarat, India (PDF) (PhD thesis). Saurashtra University. p. 87.

- ^ Sinha, Nandini (August 1, 2001). "Early Maitrakas, Landgrant Charters and Regional State Formation in Early Medieval Gujarat". Studies in History. 17 (2): 153–154. doi:10.1177/025764300101700201. S2CID 162126329 – via SAGE.

- ^ Trivedi 1961, p. 101. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTrivedi1961 (help)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Pandya, Haresh (24 May 2006). "Bapu's children swear by guns". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Menon, Aditya (9 December 2017). "Gangs of Porbandar: How Gujarat polls are the latest act in old mafia rivalries". Catch News. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ Dave, Hiral (2 April 2011). "Porbandar mourns its Godmother". The Indian Express. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ "HC gives Bhima Dula life for double murder". Times of India. 14 October 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Congman who bucks the wave". The Indian Express. 4 March 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Porbandar (Gujarat) Assembly Constituency Elections". Elections.in. 27 March 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Trivedi 1961, p. 60. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTrivedi1961 (help)

- ^ Trivedi 1961, p. 100, 111. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTrivedi1961 (help)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Trivedi 1999, p. 71.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Trivedi 1999, p. 80.

- ^ Trivedi, Harshad, R (1961). The Mers of Saurashtra: An exposition of their social structure and organisation. Baroda: Faculty of Arts, Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda. OCLC 551698930.

- ^ Trivedi 1961, p. 177. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTrivedi1961 (help)

- ^ Maddock 1993, p. 108-110.

- ^ Manorma Sharma (1 January 2007). Musical Heritage Of India. APH Publishing. p. 60. ISBN 978-81-313-0046-6. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ "Shinshoria – a traditional ear ornament". People's Archive of Rural India. 2015-02-16. Retrieved 2020-05-19.

- ^ "Vedla – earrings of the Maher community". People's Archive of Rural India. 2015-02-16. Retrieved 2020-05-19.

- ^ Krutak, Lars. "India: Land of Eternal Ink".

- ^ TRAVELS THROUGH GUJARAT, DAMAN, AND DIU. 22 February 2019. ISBN 9780244407988.

- ^ Krutak, Lars. "India: Land of Eternal Ink".

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Trivedi 1999, p. 83.

- ^ Trivedi 1999, p. 20-38.

- ^ Trivedi 1961, p. 44. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTrivedi1961 (help)

- ^ Trivedi 1999, p. 183.

- ^ Trivedi 1999, p. 184-185.

- ^ "Central List of OBCs". National Commission for Backward Classes. 10 September 1993. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ Trivedi 1961, p. 173-175. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTrivedi1961 (help)

- ^ Trivedi 1961, p. 163. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTrivedi1961 (help)

- ^ Trivedi 1961, p. 163-164. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTrivedi1961 (help)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Trivedi 1961, p. 158. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTrivedi1961 (help)

- ^ Trivedi 1961, p. 63. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTrivedi1961 (help)

- ^ Trivedi 1999, p. 71.[verification needed]

- ^ Trivedi 1961, p. 153. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTrivedi1961 (help)

- ^ Trivedi 1961, p. 157-158, 160. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTrivedi1961 (help)

- ^ Trivedi 1961, p. 161. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTrivedi1961 (help)

- ^ Trivedi 1961, p. 162. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTrivedi1961 (help)

- ^ Trivedi 1961, p. 155. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTrivedi1961 (help)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Trivedi 1961, p. 175. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTrivedi1961 (help)

- ^ Desai, Anjali H. (2007). India Guide Gujarat. ISBN 978-0978951702.

- ^ Trivedi 1961, p. 183-188. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTrivedi1961 (help)

- ^ Trivedi 1961, p. 187. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTrivedi1961 (help)

- ^ Trivedi 1961, p. 156-157. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTrivedi1961 (help)

- ^ Trivedi, Harshad R.(Author) (1986). Mers of Saurashtra Revisited and Studied in the Light of Socio-Cultural Change and Cross-Cousin Marriage. Concept publishing. p. 21. ISBN 9788170220442.

- ^ Joshi, Swati (2 December 2000). "'Godmother': Contesting Communal Politics in Drought Land". Economic and Political Weekly. 35 (49): 4304–4306 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Gangs of Porbandar: How Gujarat polls are the latest act in old mafia rivalries". CatchNews.com. Retrieved 2020-05-19.

- ^ Joshi, Rajesh (8 March 1999). "Santokben, Godmother". Outlook India. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

Sources[]

- Franco, Fernando; Macwan, Jyotsna; Ramanathan, Suguna (2004). Journeys to Freedom: Dalit Narratives. Popular Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-85604-65-7.

- Maddock, P (1993). "Idolatry in western Saurasthra: A case study of social change and proto‐modern revolution in art". South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. Journal of South Asian Studies. 16: 101–126. doi:10.1080/00856409308723194.

- Odedra, N. K. (January 2009). "Ethnobotany of Maher Tribe In Porbandar District, Gujarat, India". Core.

- Trivedi, Harshad, R (1961). "A Study of the Mers of Saurashtra: An exposition of their social structure and organization". University. Vadodara: Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda. hdl:10603/59823. OCLC 551698930.

- Trivedi, Harshad, R (1986). The Mers of Saurashtra revisited and studied in the light of socio-cultural change and cross-cousin marriage. Delhi: Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 9788170220442.

- Trivedi, Harshad, R (1999). The Mers of Saurashtra : A profile of social, economic, and political status. Delhi: Devika Publications. ISBN 9788186557204.

- Campbell, James, M (1881). Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency. Vol. 8: Kathiawar. Bombay: Government Central Press.

|volume=has extra text (help)

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mer people. |

- Ethnic groups in India

- Social groups of Gujarat