Metrosexual

Metrosexual is a portmanteau of metropolitan and sexual coined in 1994, describing a man of ambiguous sexuality, (especially one living in an urban, post-industrial, capitalist culture) who is especially meticulous about his grooming and appearance, typically spending a significant amount of time and money on shopping as part of this.[1]

The term references uncertainty as to whether a metrosexual is heterosexual, gay or a bisexual man.[2]

Origin[]

The term metrosexual originated in an article by Mark Simpson[3][4] published on November 15, 1994, in The Independent. Simpson wrote:

Metrosexual man, the single young man with a high disposable income, living or working in the city (because that's where all the best shops are), is perhaps the most promising consumer market of the decade. In the Eighties he was only to be found inside fashion magazines such as GQ. In the Nineties, he's everywhere and he's going shopping.

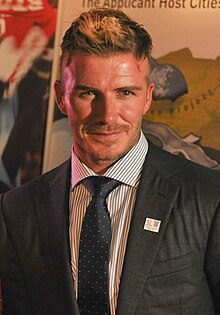

However, it was not until the early 2000s when Simpson returned to the subject that the term became globally popular. In 2002, Salon.com published an article by Simpson, which described David Beckham as "the biggest metrosexual in Britain" and offered this updated definition:

The typical metrosexual is a young man with money to spend, living in or within easy reach of a metropolis – because that's where all the best shops, clubs, gyms and hairdressers are. He might be officially gay, straight or bisexual, but this is utterly immaterial because he has clearly taken himself as his own love object and pleasure as his sexual preference.[2]

The advertising agency Euro RSCG Worldwide adopted the term shortly thereafter for a marketing study.[citation needed] Sydney's daily newspaper, The Sydney Morning Herald, ran a major feature in March 2003 titled "The Rise of the Metrosexual" (also syndicated in its sister paper The Age).[citation needed] A couple of months later, The New York Times' Sunday Styles section ran a story, "Metrosexuals Come Out".[3] The term and its connotations continued to roll steadily into more news outlets around the world. Though it did represent a complex and gradual change in the shopping and self-presentation habits of both men and women, the idea of metrosexuality was often distilled in the media down to a few men and a short checklist of vanities, like skin care products, scented candles and costly, colorful dress shirts and pricey designer jeans.[5] It was this image of the metrosexual—that of a straight young man who got pedicures and facials, practiced aromatherapy and spent freely on clothes—that contributed to a backlash against the term from men who merely wanted to feel free to take more care with their appearance than had been the norm in the 1990s, when companies abandoned dress codes, Dockers khakis became a popular brand, and XL, or extra-large, became the one size that fit all.[5]

A 60 Minutes story on 1960s–70s pro footballer Joe Namath suggested he was "perhaps, America's first metrosexual" after filming his most famous ad sporting Beautymist pantyhose.[6]

When the word first became popular, various sources attributed its origin to trendspotter Marian Salzman, but Salzman has credited Simpson as the original source for her usage of the word.[7][8][9]

Related terms[]

Over the course of the following years, other terms countering or substituting for "metrosexual" appeared. Perhaps the most widely used was "retrosexual", which in its anti- or pre-metrosexual sense was also first used by Simpson.[10] However, in later years, the term was used by some to describe men who subscribed to what they affected to be the grooming and dress standards of a previous era, such as the handsome, impeccably turned-out fictional character of Donald Draper in the television series Mad Men, itself set in an idealised version of the early 1960s New York advertising world.[11]

Another example was the short-lived "übersexual", which was coined by marketing executives and authors of The Future of Men, and was perhaps inspired by Simpson's use of the term "uber-metrosexual" to describe David Beckham.[12]

Simpson's original definition of the metrosexual was sexually ambiguous, or at least went beyond the straight/gay dichotomy. Marketers, in contrast, insisted that the metrosexual was always "straight" – they even tried to pretend that he was not vain.[12] However, they failed to convince the public, hence, says Simpson, their attempt to create the uber-straight ubersexual.

Narcissism[]

In 2002, this idea was further explored in the book Media Sport Stars: Masculinities and Moralities, (Routledge) when Gary Whannel described Beckham's: "narcissistic self-absorption", seeing it as a break from the prevailing masculine codes.[13]

Female metrosexuality[]

Female metrosexuality is a concept that Simpson explored with American writer Caroline Hagood.[14] They employed the female characters from the HBO series Sex and the City in order to illustrate examples of wo-metrosexuality, a term Hagood coined to refer to the feminine form of metrosexuality. The piece implied that, although this phenomenon would not necessarily empower women, the fact that the metrosexual lifestyle de-emphasizes traditional male and female gender roles could help women out in the long run. However, it is debatable whether the characters made famous by "Sex and the City" truly de-emphasized female gender roles, given that the series focused a high amount of attention on stereotypically feminine interests like clothing, appearance, and romantic entanglements.

Changing masculinity[]

Traditional masculine norms, as described in psychologist Ronald F. Levant's Masculinity Reconstructed are: "avoidance of femininity; restricted emotions; sex disconnected from intimacy; pursuit of achievement and status; self-reliance; strength; aggression and homophobia".[15]

Various studies, including market research by Euro RSCG, have suggested that the pursuit of achievement and status is not as important to men as it used to be; and neither is, to a degree, the restriction of emotions or the disconnection of sex from intimacy. Another norm change supported by research is that men "no longer find sexual freedom universally enthralling". Lillian Alzheimer noted less avoidance of femininity and the "emergence of a segment of men who have embraced customs and attitudes once deemed the province of women".[16]

Men's fashion magazines – such as Details, Men's Vogue, and the defunct – targeted what one Details editor called "men who moisturize and read a lot of magazines".[17]

Changes in culture and attitudes toward masculinity, visible in the media through television shows such as Queer Eye for the Straight Guy, Queer as Folk, and Will & Grace, have changed these traditional masculine norms. Metrosexuals only made their appearance after cultural changes in the environment and changes in views on masculinity.[citation needed] Simpson said in his article "Metrosexual? That rings a bell..." that "Gay men provided the early prototype for metrosexuality. Decidedly single, definitely urban, dreadfully uncertain of their identity (hence the emphasis on pride and the susceptibility to the latest label) and socially emasculated, gay men pioneered the business of accessorising—and combining—masculinity and desirability."[18]

But such probing analyses into various shoppers' psyches may have ignored other significant factors affecting men's shopping habits, foremost among them women's shopping habits. As the retail analyst Marshal Cohen explained in a 2005 article in the New York Times entitled, "Gay or Straight? Hard to Tell", the fact that women buy less of men's clothing than they used to has, more than any other factor, propelled men into stores to shop for themselves. "In 1985 only 25 percent of all men's apparel was bought by men, he said; 75 percent was bought by women for men. By 1998 men were buying 52 percent of apparel; in 2004 that number grew to 69 percent and shows no sign of slowing." One result of this shift was the revelation that men cared more about how they look than the women shopping for them had.[5]

However, despite changes in masculinity, research has suggested men still feel social pressure to endorse traditional masculine male models in advertising. Martin and Gnoth (2009) found that feminine men preferred feminine models in private, but stated a preference for the traditional masculine models when their collective self was salient. In other words, feminine men endorsed traditional masculine models when they were concerned about being classified by other men as feminine. The authors suggested this result reflected the social pressure on men to endorse traditional masculine norms.[19]

In popular culture[]

In its soundbite diffusion through the channels of marketeers and popular media, who eagerly and constantly reminded their audience that the metrosexual was straight, the metrosexual has congealed into something more digestible for consumers: a heterosexual male who is in touch with his feminine side — he color-coordinates, cares deeply about exfoliation, and has perhaps manscaped.[20] Men did not go to shopping malls, so consumer culture promoted the idea of a sensitive man who went to malls, bought magazines and spent freely to improve his personal appearance. As Simpson put it:[21]

"For some time now, old-fashioned (re)productive, repressed, unmoisturized heterosexuality has been given the pink slip by consumer capitalism. The stoic, self-denying, modest straight male didn't shop enough (his role was to earn money for his wife to spend), and so he had to be replaced by a new kind of man, one less certain of his identity and much more interested in his image — that's to say, one who was much more interested in being looked at (because that's the only way you can be certain you actually exist). A man, in other words, who is an advertiser's walking wet dream."

— Mark Simpson, Salon.com

In contrast, there is also the view that metrosexuality is at least partly a naturally occurring phenomenon, much like the Aesthetic Movement of the 19th century, and that the metrosexual is a modern incarnation of a dandy. Fashion designer Tom Ford drew parallels when he described David Beckham as a: "total modern dandy". Ford suggested that "macho" sporting role models who also care about fashion and appearance influence masculine norms in wider society.[22]

See also[]

- Bishōnen

- Chad (slang)

- Dandy

- Fop

- Himbo

- Ikemen

- Pink capitalism

- Homomasculinity

- Lumbersexual

- Kkonminam

- Macaroni (fashion)

- Metrosexuality (TV series)

- New Romantic

- "South Park Is Gay!" (TV episode)

References[]

- ^ Collins, William. "Metrosexual". Collins Unabridged English Dictionary. Harper Collins. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Simpson, Mark (22 July 2002). "Meet the metrosexual". Salon. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b St John, Warren (22 June 2003). "Metrosexuals come out". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ Simpson, Mark. "Here come the mirror men: why the future is metrosexual". marksimpson.com. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Colman, David (19 June 2005). "Gay or Straight? Hard to Tell". The New York Times.

- ^ Hancock, David (16 November 2006). "Broadway Joe: Football great talks about his drinking problem with Bob Simon". CBS News 60 Minutes. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ Salzman, Marian (26 February 2014). "The Man Brand". Forbes. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ^ Simpson, Mark. "Metrosexual? That rings a bell..." marksimpson.com. Archived from the original on 24 January 2007. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ Hoggard, Liz (29 June 2003). "She's the bees knees". The Observer. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ McFedries, Paul. "retrosexual". wordspy.com. Wordspy. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ Lipke, David; Thomas, Brenner (21 June 2010). "Men's Trend: The Retrosexual Revolution". Women's Wear Daily. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Simpson, Mark (2005). "Metrodaddy v. Ubermummy". 3am Magazine. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ Coad, David (2008). The Metrosexual: Gender, Sexuality and Sport. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, Albany. p. 187. ISBN 9780791474099. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ Huffington Post Mark Simpson and Caroline Hagood on Wo-Metrosexuality and the City April 13, 2010

- ^ Levant, Ronald F.; Kopecky, Gini (1995). Masculinity Reconstructed: Changing the Rules of Manhood—At Work, in Relationships, and in Family Life. New York: Dutton. ISBN 978-0452275416.

- ^ Alzheimer, Lillian (22 June 2003). "Metrosexuals: The Future of Men?". Euro RSCG. Archived from the original on 3 August 2003. Retrieved 15 December 2003.

- ^ Fine, Jon (28 February 2005). "Counter couture: men's fashion titles on rise even as ad pages fall". Ad Age. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ^ Simpson, Mark (22 June 2003). "Metrosexual? That rings a bell..." Independent on Sunday; later MarkSimpson.com. Archived from the original on 24 January 2007. Retrieved 2003-10-13.

- ^ Martin, Brett A. S.; Juergen Gnoth (30 January 2009). "Is the Marlboro Man the Only Alternative? The Role of Gender Identity and Self-Construal Salience in Evaluations of Male Models" (PDF). Marketing Letters (20). pp. 353–367.

- ^ Mark Simpson in The Guardian January 2012

- ^ Simpson, Mark (22 June 2002). "Meet the metrosexual". Salon.com; later MarkSimpson.com. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 21 September 2006.

- ^ Coad, David (2008). The Metrosexual: Gender, Sexuality and Sport. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, Albany. pp. 186–7. ISBN 9780791474099. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

Further reading[]

- Simpson, Mark (2011).'Metrosexy: A 21st Century Self-Love Story'

- O'Reilly, Ann; Matathia, Ira; Salzman, Marian (2005). The Future of Men, Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-4039-6882-9.

- Rodney E. Lippard (2006). "The Metrosexual and Youth Culture". In Greenwood Publishing Group (ed.). Contemporary Youth Culture: An International Encyclopedia (illustrated ed.). pp. 288–291. ISBN 0-313-33729-2.

External links[]

| Look up metrosexual or ubersexual in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- 'Metrodaddy Speaks!' Mark Simpson answers questions from the global media in 2004

- 2005 reassessment by Simpson

- "The Metrosexual Defined; Narcissism and Masculinity in Popular Culture" Article exploring the commercial and sociological sides of the metrosexual

- [1] The Metrosexual: Gender, Sexuality, and Sport by David Coad. Albany, New York: SUNY Press, 2008

- Media Sport Stars: Masculinities and Moralities, Gary Whannel, Jstor, 2002[permanent dead link]

- Popular culture neologisms

- LGBT and society

- Narcissism

- Fashion

- Stereotypes

- Stereotypes of men

- Stereotypes of urban people

- Terms for men

- Subcultures

- 2000s fads and trends

- 1990s neologisms

- Heterosexuality