Michael Collins (film)

| Michael Collins | |

|---|---|

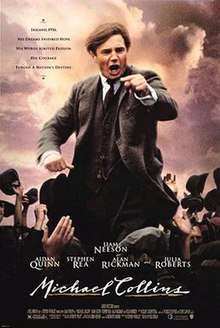

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Neil Jordan |

| Written by | Neil Jordan |

| Produced by | Stephen Woolley |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Chris Menges |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Elliot Goldenthal |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 132 minutes[1] |

| Countries | Ireland United Kingdom United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $25 million[2] |

| Box office | $27.5 million[3] |

Michael Collins is a 1996 biographical period drama film written and directed by Neil Jordan and starring Liam Neeson as the Irish revolutionary, soldier, and politician Michael Collins, who was a leading figure in the early-20th-century Irish struggle for independence. It won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival[4] and was also nominated for Best Original Score and Best Cinematography at the 69th Academy Awards.

Plot[]

At the close of the Easter Rising in 1916, the besieged Irish rebels surrender to the British Army at the Irish Republican headquarters in Dublin. Several key figures of the Rising; Patrick Pearse, Thomas MacDonagh, Tom Clarke and James Connolly are executed. Éamon de Valera is spared execution due to his American citizenship, but is imprisoned alongside Michael Collins and Harry Boland.

The 1918 Irish general election results in the victorious Sinn Féin party to unilaterally declare Irish independence, beginning the Irish War of Independence. De Valera is elected President, Collins is appointed Director of Intelligence for the emerging IRA. Ned Broy, officially a member of the loyalist G Division sympathizes with the independence cause, and tips Collins off that the Castle intends to arrest the entire Cabinet that evening. De Valera, sensing that the arrest will spark an international outcry dissuades his cabinet from going into hiding, and allow their arrests to take place. Collins and Boland evade arrest, though there is no response to the wider action.

As the last senior leader still free, Collins begins a counter-intelligence campaign with help from Broy. Numerous assassinations take place on agents and Irish collaborators by the IRA's Dublin Brigade. De Valera soon breaks out of Lincoln Prison, but announces upon returning to Ireland that he will go to the United States to seek President Woodrow Wilson's official recognition of the Irish Republic. The war continues to intensify, the British assign SIS Officer Soames to counter the IRA, though he and several of his agents are assassinated in kind. To retaliate, the Black and Tans are sent to Dublin who brutally suppress unarmed civilians in support of independence, culminating in a massacre at Croke Park, where 14 people are killed during a peaceful Gaelic football game. Broy's assistance to Collins is also discovered by Soames, who is subsequently tortured and killed.

De Valera returns from America, unable to secure President Wilson's support. The British hint at direct communication with the Irish, though Collins' guerilla campaign has boded poorly for Ireland's image, therefore de Valera decrees that the IRA must fight as a conventional army; though Collins knows that this will just lead to another defeat against the might of the British Empire. Adamant at securing peace, de Valera orders an attack on The Custom House, but the IRA suffer heavy casualties and the attack fails catastrophically. Despite the desperate situation the IRA now find themselves in, the British unexpectedly call for a ceasefire.

Collins is sent to London to negotiate Irish interests as part of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, which is signed in 1921. Though the Republic is not immediately granted independence, the treaty grants Ireland to achieve it overtime whilst also becoming a British dominion during the interim, plus the cost of six of the nine Ulster counties. De Valera is furious upon learning of this, who sought unconditional independence for Ireland. As a result, de Valera and his supporters resign in protest, including Boland. The subsequent people's vote backs the terms of the treaty, though de Valera rejects the result, and in 1922 leads a seizure on the Four Courts in Dublin, the IRA lead by Collins are ordered to retake it. In the Battle of Dublin, Boland is killed.

Devastated upon learning his friends death, Collins journeys to West Cork, where de Valera is in hiding to mediate peace. Collins however is misdirected by de Valera's associates, and he is lead into an ambush where he is shot and killed. Kitty Kiernan, the love interest of Collins is informed of the latter's death just as she tries on a wedding gown.

Cast[]

- Liam Neeson as Michael Collins

- Aidan Quinn as Harry Boland

- Stephen Rea as Ned Broy

- Alan Rickman as Éamon de Valera

- Julia Roberts as Kitty Kiernan

- Ian Hart as Joe O'Reilly

- Brendan Gleeson as Liam Tobin

- Seán McGinley as Smith

- Gerard McSorley as Cathal Brugha

- Owen O'Neill as Rory O'Connor

- Charles Dance as Soames, the British SIS officer who commands the Cairo Gang

- Jonathan Rhys Meyers as Collins's Assassin

- Ian McElhinney as Belfast Detective

- Stuart Graham as Tom Cullen

- Gary Lydon as Squad Youth

- Jean Kennedy Smith (Uncredited cameo)

Production[]

Michael Cimino wrote a script and was involved in pre-production work on a possible Collins film for over a year in the early 1990s with Gabriel Byrne attached to star. Cimino was fired over budget concerns. Neil Jordan mentions in his film diary that Kevin Costner had also been interested in developing a movie about Collins and had visited Béal na Bláth and the surrounding areas.[5]

The film was scripted and directed by Neil Jordan. The soundtrack was written by Elliot Goldenthal. The film was an international co-production between companies in Ireland and the United States.[6] With a budget estimated at $25 million, with 10%-12% from the Irish Film Board, it was one of the most expensive films ever produced in Ireland.[2] While filming, the breakdown of the IRA ceasefire caused the film's release to be delayed from June to December which caused Warner Bros. executive Rob Friedman to pressure the director to reshoot the ending to focus on the love story between Collins and Kiernan, in an attempt to downplay the breakdown of Anglo-Irish Treaty negotiations.[2]

A number of Irish actors auditioned for the part of de Valera but Jordan felt they weren't able to find a real character and were playing a stereotype of de Valera. Jordan met with John Turturro about the role before casting Alan Rickman. Jordan initially envisioned Stephen Rea playing Harry Boland, but then decided the role of Broy would give Rea more of a challenge. Matt Dillon and Adam Baldwin also auditioned for the role.[5] Aengus O'Malley, a great grandnephew of Michael Collins, played the role of a student filmed in Marsh's Library.

Historical alterations[]

Although based on historical events, the film contains some alterations and fictionalisations, such as the dramatised circumstances of Harry Boland's death and Ned Broy's fate and significant alterations to the formative years of Dáil Éireann and to the prelude to the events of the first "Bloody Sunday" at Croke Park. Neil Jordan defended his film by saying that it could not provide an entirely accurate account of events since it was a two-hour film that had to be understandable to an international audience that would not know the minutiae of Irish history.[7] The documentary on the DVD release of the film also discusses its fictional aspects.

The critic Roger Ebert referred to the closing quotation from de Valera that history would vindicate Collins at his own expense by writing that "even Dev could hardly have imagined this film biography of Collins, which portrays De Valera as a weak, mannered, sniveling prima donna whose grandstanding led to decades of unnecessary bloodshed in, and over, Ireland."[8] Jordan's film heavily implies that de Valera had a hand in the assassination of Michael Collins.

Boland did not die in the manner suggested by the film. He was shot in a skirmish with Irish Free State soldiers in The Grand Hotel, Skerries, County Dublin, in the aftermath of the Battle of Dublin. The hotel has since been demolished, but a plaque was put where the building used to be. His last words in the film ("Have they got Mick Collins yet?") are based on a well-known tradition.[9]

Soundtrack[]

The score was written by acclaimed composer Elliot Goldenthal, and features performances by Sinéad O'Connor. Frank Patterson also performs with the Cafe Orchestra in the film and on the album.

Ratings[]

The Irish Film Censor initially intended to give the film an over-15 certificate, but later decided that it should be released with a PG certificate because of its historical importance. The censor issued a press statement defending his decision, claiming the film was a landmark in Irish cinema and that "because of the subject matter, parents should have the option of making their own decision as to whether their children should see the film or not".[6] The video release was given a 12 certificate.

The film was rated 15 in the United Kingdom by the British Board of Film Classification.[10]

The film was rated R in the United States by the Motion Picture Association of America.

Reception[]

The film became the highest-grossing film ever in Ireland upon its release, making IR£ 4 million. In 2000, it was second only to Titanic in this category.[6]

The film received generally positive reviews from critics, but was criticized by some for its historical inaccuracies.[11] On Rotten Tomatoes, it has an approval rating of 77% based on 47 reviews, with an average rating of 6.90/10. The site's consensus states: "As impressively ambitious as it is satisfyingly impactful, Michael Collins honors its subject's remarkable achievements with a magnetic performance from Liam Neeson in the title role."[12] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 60 out of 100 based on reviews from 20 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[13]

Irish journalist Kevin Myers, who is known for his criticism of physical force Irish republicanism, praised the film in his Irish Times column, writing, "I think it is magnificent. I was unable to leave the cinema at its end, so profoundly moved and saddened was I; and I can understand why Neil Jordan has been so personally offended by criticism of the film in Ireland and in Britain. It is a film which shows his passionate commitment to the subject, to the film, to Ireland, and, I believe, to peace."[14]

Roger Ebert gave the film three stars out of four.[8]

Accolades[]

- Academy Awards - Nominated Best Cinematography (Chris Menges)

- Academy Awards - Nominated Best Original Dramatic Score (Elliot Goldenthal)

- Evening Standard British Film Awards - Winner Best Actor (Liam Neeson)

- Golden Globe Awards - Nominated Best Actor in a Motion Picture - Drama (Liam Neeson)

- Los Angeles Film Critics Association - Winner Best Cinematography (Chris Menges; tied with John Seale for The English Patient)

- Venice Film Festival - Winner Golden Lion (Neil Jordan), Winner Best Actor (Liam Neeson)

References[]

- ^ "MICHAEL COLLINS". British Board of Film Classification.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Goldstone, Patricia. Making the world safe for tourism, Yale University Press, 2001. p. 139 ISBN 0-300-08763-2

- ^ "Michael Collins (1996) - Financial Information". The-numbers.com. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ "The awards of the Venice Film Festival". Labiennale.org. Retrieved 30 September 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Neil Jordan, Michael Collins, Plume Press, 1996 ISBN 0-452-27686-1

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Between Irish National Cinema and Hollywood: Neil Jordan's Michael Collins" (PDF). Retrieved 30 September 2010.

- ^ "Michael Collins", The South Bank Show, 27 October 1996.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ebert, Roger (25 October 1996). "Michael Collins movie review & film summary (1996)". Chicago Sun Times.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, David. Harry Boland's Irish Revolution, Cork University Press. p. 8. ISBN 1-85918-222-4

- ^ "MICHAEL COLLINS | British Board of Film Classification". BBFC.co.uk. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ Flynn, Roderick and Patrick Brereton. "Michael Collins", Historical Dictionary of Irish Cinema, Scarecrow Press, 2007. Page 252. ISBN 978-0-8108-5557-1

- ^ "Michael Collins (1996)". Rotten Tomatoes.

- ^ "Michael Collins". Metacritic.

- ^ Kevin Myers, From the Irish Times column An Irishman's Diary (Dublin: Four Courts, 2000), p. 41

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Michael Collins (film) |

- Michael Collins at IMDb

- Seán Farrell Moran, movie review, "Michael Collins," in The American Historical Review, 1997.

- Review of Michael Collins

- Michael Collins at AllMovie

- Michael Collins at Box Office Mojo

- Michael Collins at Rotten Tomatoes

- 1996 films

- English-language films

- 1990s biographical drama films

- 1990s historical drama films

- American films

- American biographical drama films

- American historical drama films

- British Empire war films

- Epic films based on actual events

- Irish Civil War films

- Irish War of Independence films

- Films about the Irish Republican Army

- Films directed by Neil Jordan

- Films set in 1916

- Films set in 1918

- Films set in 1919

- Films set in 1920

- Films set in 1921

- Films set in 1922

- Films set in Dublin (city)

- Films shot in Ireland

- The Geffen Film Company films

- Golden Lion winners

- Warner Bros. films

- Films scored by Elliot Goldenthal

- Cultural depictions of Michael Collins (Irish leader)

- Cultural depictions of Éamon de Valera

- Historical epic films