Gondor

| Gondor | |

|---|---|

| J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium location | |

Coat of arms bearing the white tree, Nimloth the fair[T 1] | |

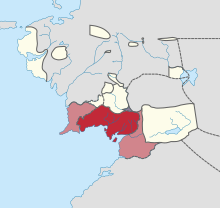

Gondor (red) and area under its control (pink) within Middle-earth | |

| First appearance | The Lord of the Rings |

| Information | |

| Type | Southern Númenórean realm in exile |

| Ruler | Kings of Gondor; Stewards of Gondor |

| Other name(s) | The South-kingdom |

| Location | Northwest Middle-earth |

| Capital | Osgiliath, then Minas Tirith |

| Founder | Isildur and Anárion |

Gondor is a fictional kingdom in J. R. R. Tolkien's writings, described as the greatest realm of Men in the west of Middle-earth at the end of the Third Age. The third volume of The Lord of the Rings, The Return of the King, is largely concerned with the events in Gondor during the War of the Ring and with the restoration of the realm afterward. The history of the kingdom is outlined in the appendices of the book.

According to the narrative, Gondor was founded by the brothers Isildur and Anárion, exiles from the downfallen island kingdom of Númenor. Along with Arnor in the north, Gondor, the South-kingdom, served as a last stronghold of the Men of the West. After an early period of growth, Gondor gradually declined as the Third Age progressed, being continually weakened by internal strife and conflict with the allies of the Dark Lord Sauron. By the time of the War of the Ring, the throne of Gondor is empty, though its principalities and fiefdoms still pay deference to the absent king by showing their loyalty to the Stewards of Gondor. The kingdom's ascendancy was restored only with Sauron's final defeat and the crowning of Aragorn as king.

Based upon early conceptions, the history and geography of Gondor were developed in stages as Tolkien extended his legendarium while writing The Lord of the Rings. Critics have noted the contrast between the cultured but lifeless Stewards of Gondor, and the simple but vigorous leaders of the Kingdom of Rohan, modelled on Tolkien's favoured Anglo-Saxons. Scholars have noted parallels between Gondor and the Normans, Ancient Rome, the Vikings, the Goths, the Langobards, and the Byzantine Empire.

Literature[]

Fictional etymology[]

Tolkien intended the name Gondor to be Sindarin for "land of stone".[T 2][T 3] This is echoed in the text of The Lord of the Rings by the name for Gondor among the Rohirrim, Stoningland.[T 4] Tolkien's early writings suggest that this was a reference to the highly developed masonry of Gondorians in contrast to their rustic neighbours.[T 5] This view is supported by the Drúedain terms for Gondorians and Minas Tirith—Stonehouse-folk and Stone-city.[T 6] Tolkien denied that the name Gondor had been inspired by the ancient Ethiopian citadel of Gondar, stating that the root Ond went back to an account he had read as a child mentioning ond ("stone") as one of only two words known of the pre-Celtic languages of Britain.[T 7] Gondor is also called the South-kingdom or Southern Realm, and together with Arnor as the Númenórean Realms in Exile. Researchers Wayne G. Hammond and Christina Scull have proposed a Quenya translation of Gondor: Ondonórë.[1] The Men of Gondor are nicknamed "Tarks" (from Quenya tarkil "High Man", Numenorean)[T 8] by the orcs of Mordor.[T 9]

Fictional geography[]

Country[]

Gondor's geography is illustrated in the maps for The Lord of the Rings made by Christopher Tolkien on the basis of his father's sketches, and geographical accounts in The Rivers and Beacon-Hills of Gondor, Cirion and Eorl, and The Lord of the Rings. Gondor lies in the west of Middle-earth, on the northern shores of Anfalas[T 10][T 11] and the Bay of Belfalas[T 12] with the great port of Pelargir near the river Anduin's delta in the fertile[T 13] and populous[T 11] region of Lebennin,[T 14] stretching up to the White Mountains (Sindarin: Ered Nimrais, "Mountains of White Horns"). Near the mouths of Anduin was the island of Tolfalas.[T 15]

To the north-west of Gondor lies Arnor; to the north, Gondor is neighboured by Wilderland and Rohan; to the north-east, by Rhûn; to the east, across the great river Anduin and the province of Ithilien, by Mordor; to the south, by the deserts of northern Harad. To the west lies the Great Sea.[T 16]

The wide land to the west of Rohan was Enedwaith; in some of Tolkien's writings it is part of Gondor, in others not.[T 17][T 18][T 19][T 20] The hot and dry region of South Gondor was by the time of the War of the Rings "a debatable and desert land", contested by the men of Harad.[T 14]

The region of Lamedon and the uplands of the prosperous Morthond, with the desolate Hill of Erech,[T 21] lay to the south of the White Mountains, while the populous[T 4] valleys of Lossarnach were just south of Minas Tirith. The city's port was also a few miles south at Harlond, where the great river Anduin made its closest approach to Minas Tirith. Ringló Vale lay between Lamedon and Lebennin.[T 22]

The region of Calenardhon lay to the north of the Grey Mountains; it was granted independence as the kingdom of Rohan.[T 20] To the northeast, the river Anduin enters the hills of the Emyn Muil and passes the Sarn Gebir, dangerous straits, above a large river-lake, Nen Hithoel. Its entrance was once the northern border of Gondor, and is marked by the Gates of Argonath, an enormous pair of kingly statues, as a warning to trespassers. At the southern end of the lake are the hills of Amon Hen (the Hill of Seeing) and Amon Lhaw (the Hill of Hearing) on the west and east shores; below Amon Hen is the lawn of Parth Galen, where the Fellowship disembarked and was then broken, with the capture of Merry and Pippin, and the death of Boromir. Between the two hills is a rocky islet, Tol Brandir, which partly dams the river; just below it is an enormous waterfall, the Falls of Rauros, over which Boromir's funeral-boat is sent. Further down the river are the hills of Emyn Arnen.[T 23]

Capital, Minas Tirith[]

The capital of Gondor at the end of the Third Age, Minas Tirith (Sindarin: "Tower of guard"[2]), lay at the eastern end of the White Mountains, built around a shoulder of Mount Mindolluin. The city is sometimes called "the White Tower", a synecdoche for the city's most prominent building in its Citadel, the seat of the city's administration. The head of government is the Lord of the City, a role fulfilled by the Stewards of Gondor. Other officials included the Warden of the Houses of Healing and the Warden of the Keys. The Warden of the Keys was in charge of the city's security, especially its gates, and the safe-keeping of its treasury, notably the Crown of Gondor; he had full command of the city when it was besieged by the forces of Mordor.[T 24]

Minas Tirith had seven walls: each wall held a gate, and each gate faced a different direction from the next, facing alternately somewhat north or south. Each level was about 100 ft (30 m) higher than the one below it, and each surrounded by a high stone wall colored in white, with the exception of the wall of the First Circle (the lowest level), which was black, built of the same material used for Orthanc. This outer wall was also the tallest, longest and strongest of the city's seven walls; it was vulnerable only to earthquakes capable of rending the ground where it stood.[T 25] The Great Gate of Minas Tirith, constructed of iron and steel and guarded by stone towers and bastions, was the main gate on the first wall level of the city. In front of the Great Gate was a large paved area called the Gateway. The main roads to Minas Tirith met here: the North-way that became the Great West Road to Rohan; the South Road to the southern provinces of Gondor; and the road to Osgiliath, which lay to the north-east of Minas Tirith. Except for the high saddle of rock which joined the west of the hill to Mindolluin, the city was surrounded by the Pelennor, an area of farmlands.

The city's main street zigzagged up the eastern hill-face and through each of the gates and the central spur of rock. It led to the Citadel through the Seventh Gate on its eastern part. The White Tower, at the city's highest level with a commanding view of the lower vales of Anduin, stood in the Citadel, 700 feet higher than the surrounding plains, protected by the seventh and innermost wall atop the spur. Originally constructed by a king of yore, it is also known as the Tower of Ecthelion, the Steward of Gondor who had it re-built. The seat of the rulers of Gondor, the Kings and the Stewards, the tower stood 300 ft (91 m) tall, so that its pinnacle was some one thousand feet (300 m) above the plain. The main doors of the tower faced east, onto the Court of the Fountain. Inside was the Tower Hall, the great throne-room where the Kings (or Stewards) held court. The Seeing-stone of Minas Tirith, used by Denethor in The Return of the King, rested in a secret chamber at the top of the Tower. There was a buttery of the Guards of the Citadel in the basement of the tower. Behind the tower, reached from the sixth level, was a saddle leading to the necropolis of the Kings and Stewards.[a]

Within the Court of the Fountain stood the White Tree, the symbol of Gondor. It was dry throughout the centuries that Gondor was ruled by the Stewards; Aragorn brought a sapling of the White Tree into the city on his return as King. John Garth writes that the White Tree has been likened to the Dry Tree of the 14th century Travels of Sir John Mandeville.[5][3] The tale runs that the Dry Tree has been dry since the crucifixion of Christ, but that it will flower afresh when "a prince of the west side of the world should sing a mass beneath it".[3] The apples of the trees allow people to live for 500 years.[4]

The topmost level also contained lodgings for the Steward of Gondor, the King's House, Merethrond the Hall of Feasts, barracks for the companies of the Guard of the Citadel, and other buildings for soldiers. In The Return of the King, the hobbit Pippin Took was appointed to serve with the Guard.

Tolkien's map-notes for the illustrator Pauline Baynes indicate that the city had the latitude of Ravenna, an Italian city on the Mediterranean Sea, though it lay "900 miles east of Hobbiton more near Belgrade".[6][7][b] The Warning beacons of Gondor were atop a line of foothills running back west from Minas Tirith towards Rohan.

Dol Amroth[]

Dol Amroth (Sindarin: "the Hill of Amroth"[9]) was a fortress-city on a peninsula jutting westward into the Bay of Belfalas, on Gondor's southern shore. It is also the name of the port city, one of the five great cities of Gondor, and the seat of the principality of the same name, founded by prince Galador.[T 26] The whimsical poem "The Man in the Moon Came Down Too Soon" in The Adventures of Tom Bombadil tells how the Man in the Moon fell one night into "the windy Bay of Bel"; his fall is marked by the tolling of a bell in the Seaward Tower (Tirith Aear) of Dol Amroth, and he recovers at an inn in the city.[T 27]

Its ruler, the Prince of Dol Amroth, is subject to the sovereignty of Gondor.[T 28] The principality's boundaries are not explicitly defined, though the Prince ruled Belfalas as a fief, as well as an area to the east on the map labelled Dor-en-Ernil ("The Land of the Prince").[T 12] Imrahil, Prince of Dol Amroth in The Return of the King, was linked by marriage both to the Stewards of Gondor and to the Kings of Rohan.[10] He was brother of Lady Finduilas and uncle to her sons Boromir and Faramir;[T 29] a kinsman of Théoden;[T 30] and the father of Éomer's wife Lothíriel.[10][T 31] Imrahil played a major part in the defence of Minas Tirith; the soldiers whom Imrahil led to Minas Tirith formed the largest contingent from the hinterland to the defence of the city.[11][T 32] They marched under a banner "silver upon blue",[T 1] bearing "a white ship like a swan upon blue water".[T 33]

Some like Finduilas are of Númenórean descent,[12] and still speak the Elvish language.[T 2] Tolkien wrote about the city's protective sea-walls and described Belfalas as a "great fief".[T 21] Prince Imrahil's castle is by the sea; Tolkien described him as "of high blood, and his folk also, tall men and proud with sea-grey eyes".[T 34] Local tradition claimed that the line's forefather, Imrazôr the Númenórean had married an Elf, though the line remained mortal.[T 25][13][14]

Fictional history[]

Pre-Númenórean[]

The first people in the region were the Drúedain, a hunter-gatherer people of Men who arrive in the First Age. They were pushed aside by later settlers and came to live in the pine-woods of the Druadan Forest[T 6] by the north-eastern White Mountains.[T 35] The next people settled in the White Mountains, and became known as the Men of the Mountains. They built a subterranean complex at Dunharrow, later known as the Paths of the Dead, which extended through the mountain-range from north to south.[T 13] They became subject to Sauron in the Dark Years. Fragments of pre-Númenórean languages survive in later ages in place-names such as Erech, Arnach, and Umbar.[T 36]

Númenórean kingdom[]

The shorelands of Gondor were widely colonized by the Númenóreans from the middle of the Second Age, especially by Elf-friends loyal to Elendil.[T 37] His sons Isildur and Anárion landed in Gondor after the drowning of Númenor, and co-founded the Kingdom of Gondor. Isildur brought with him a seedling of Nimloth (Sindarin: nim, "white" and loth, "blossom"[15]) the Fair, the white tree from Númenór. This tree and its descendants came to be called the White Tree of Gondor, and appears on the kingdom's coat of arms. Elendil, who founded the Kingdom of Arnor to the north, was held to be the High King of all the lands of the Dúnedain.[T 18] Isildur established the city of Minas Ithil (Sindarin: "Tower of the Moon") while Anárion established the city of Minas Anor (Sindarin: "Tower of the Sun").[T 18]

Sauron survived the destruction of Númenor and secretly returned to his realm of Mordor, soon launching a war against the Númenórean kingdoms. He captured Minas Ithil, but Isildur escaped by ship to Arnor; meanwhile, Anárion was able to defend Osgiliath.[T 37] Elendil and the Elven-king Gil-galad formed the Last Alliance of Elves and Men, and together with Isildur and Anárion, they besieged and defeated Mordor.[T 37] Sauron was overthrown; but the One Ring that Isildur took from him was not destroyed, and thus Sauron continued to exist.[T 38]

Both Elendil and Anárion were killed in the war, so Isildur conferred rule of Gondor upon Anárion's son Meneldil, retaining suzerainty over Gondor as High King of the Dúnedain. Isildur and his three elder sons were ambushed and killed by Orcs in the Gladden Fields. Isildur's remaining son Valandil did not attempt to claim his father's place as Gondor's monarch; the kingdom was ruled solely by Meneldil and his descendants until their line died out.[T 38]

Third Age, under the Stewards[]

During the early years of the Third Age, Gondor was victorious and wealthy, and kept a careful watch on Mordor, but the peace ended with Easterling invasions.[T 40] Gondor established a powerful navy and captured the southern port of Umbar from the Black Númenóreans,[T 40] becoming very rich.[T 18] As time went by, Gondor neglected the watch on Mordor. There was a civil war, giving Umbar the opportunity to declare independence.[T 40] The kings of Harad grew stronger, leading to fighting in the south.[T 41] With a Great Plague the population began a steep decline.[T 40] The capital was moved from Osgiliath to the less affected Minas Anor and evil creatures returned to the mountains bordering Mordor. There was war with the Wainriders, a confederation of Easterling tribes, and Gondor lost its line of kings.[T 42] The Ringwraiths captured and occupied Minas Ithil[T 37] which became Minas Morgul, "the Tower of Black Sorcery".[T 43][T 37][T 18] At this time Minas Anor was renamed to Minas Tirith, in constant watch of its now defiled twin city. Without kings, Gondor was ruled by stewards for many generations, father to son; despite their exercise of power and hereditary status, they were never accepted as kings, or sat in the high throne.[T 44][d] After several attacks by evil forces the province of Ithilien[T 11] and the city of Osgiliath were abandoned.[T 18][T 40] Later the forces of Gondor, led by Aragorn under the alias Thorongil, attacked Umbar and destroyed the Corsair fleet, allowing Denethor II to devote his attention to Mordor.[T 39][17]

War of the Ring and restoration[]

Denethor sent his son Boromir to Rivendell for advice as war loomed. There, Boromir attended the Council of Elrond, saw the One Ring, and suggested it be used as a weapon to save Gondor. Elrond rebuked him, explaining the danger of such use, and instead, the hobbit Frodo was made ring-bearer, and a Fellowship, including Boromir, was sent on a quest to destroy the Ring.[T 45] Growing in strength, Sauron attacked Osgiliath, forcing the defenders to leave, destroying the last bridge across the Anduin behind them. Minas Tirith then faced direct land attack from Mordor, combined with naval attack by the Corsairs of Umbar. The hobbits Frodo and Sam travelled through Ithilien, and were captured by Faramir, Boromir's brother, who held them at the hidden cave of Henneth Annûn, but aided them to continue their quest.[T 46] Aragorn summoned the Dead of Dunharrow to destroy the forces from Umbar, freeing men from the southern provinces of Gondor such as Dol Amroth[T 11][T 12] to come to the aid of Minas Tirith.

Before the Battle of the Pelennor Fields, the Great Gate was breached by Sauron's forces led by the Witch-king of Angmar. He spoke "words of power" as the battering ram named Grond attacked the Great Gate; it burst asunder as if "stricken by some blasting spell", with "a flash of searing lightning, and the doors tumbled in riven fragments to the ground.[T 25] The Witch-king rode through the Gate where Gandalf awaited him, but left shortly afterwards to meet the Riders of Rohan in battle. Gondor, with the support of Rohirrim as cavalry, repelled the invasion by Mordor. Following the death of Denethor and the incapacity of Faramir, Prince Imrahil became the effective lord of Gondor.[18]

When Imrahil declined to send the entirety of Gondor's army against Mordor, Aragorn led a smaller army to the Black Gate of Mordor to distract Sauron from Frodo's quest.[18] The hobbits succeeded, and with Sauron defeated, the war and the Third Age ended. The Great Gate was rebuilt with mithril and steel by Gimli and Dwarves from the Lonely Mountain. Aragorn's coronation was held on the Gateway, where he was pronounced King Elessar of both Gondor and Arnor, the sister kingdom in the north.[T 47][T 41][T 48][T 49]

Concept and creation[]

Tolkien's original thoughts about the later ages of Middle-earth are outlined in his first, mid-1930s, sketches for the legend of Númenor; these already contain a semblance of Gondor.[T 50] The appendices to The Lord of the Rings were brought to a finished state in 1953–54, but a decade later, during preparations for the release of the Second Edition, Tolkien elaborated the events that had led to Gondor's civil war, introducing the regency of Rómendacil II.[T 51] The final development of the history and geography of Gondor took place around 1970, in the last years of Tolkien's life, when he invented justifications for the place-names and wrote full narratives for the stories of Isildur's death and of the battles with the Wainriders and the Balchoth (published in Unfinished Tales).[T 52]

Tolkien describes an early population of elves in the Dol Amroth region, writing many accounts of its early history. In one version, a haven and a small settlement were founded in the First Age by seafaring Sindar from the west havens of Beleriand who fled in three small ships when the power of Morgoth overwhelmed the Eldar and the Atani; the Sindar were joined later by Silvan Elves who came down Anduin seeking the sea.[T 53] Another account states that the haven was established in the Second Age by Sindarin Elves from Lindon, who learned the craft of shipbuilding at the Grey Havens and then settled at the mouth of the Morthond.[T 53] Other accounts say that Silvan Elves accompanied Galadriel from Lothlórien to this region after the defeat of Sauron at Eriador in the middle of the Second Age,[T 53] or that Amroth ruled among the Nandorin Elves here in the Second Age.[T 54] Elves continued to live there well into the Third Age, until the last ship departed from Edhellond for the Undying Lands. Amroth, King of Lothlórien from the beginning of the Third Age,[T 53] left his realm behind in search of his beloved Nimrodel, a Nandorin who had fled from the horror unleashed by the Dwarves in Moria. He waited for her at Edhellond, for their final voyage together into the West. But Nimrodel, who loved Middle-earth as much as she did Amroth, failed to join him. When the ship was blown prematurely out to sea, he jumped overboard in a futile attempt to reach the shore to search for her, and drowned in the bay.[T 53] Mithrellas, a Silvan Elf and one of the companions of Nimrodel, is said to have become the foremother of the line of the Princes of Dol Amroth.[T 53][19]

According to an alternate account about the line of the Princes of Dol Amroth cited in Unfinished Tales, they were descendants of a family of the Faithful from Númenor who had ruled over the land of Belfalas since the Second Age, before Númenor was destroyed. This family of Númenóreans were akin to the Lords of Andúnië, and thus related to Elendil and descended from the House of Elros. After the Downfall of Númenor, they were created the "Prince of Belfalas" by Elendil[T 20] Unfinished Tales provides an account of "Adrahil of Dol Amroth" who fought under King Ondoher of Gondor against the Wainriders, which predates Amroth's drowning in TA 1981.[T 42]

| Situation | Gondor | Rohan |

|---|---|---|

| Leader's behaviour on meeting trespassers |

Faramir, son of Ruling Steward Denethor courteous, urbane, civilised |

Éomer, nephew of King Théoden "compulsively truculent" |

| Ruler's palace | Great Hall of Minas Tirith large, solemn, colourless |

Mead hall of Meduseld, simple, lively, colourful |

| State | "A kind of Rome", subtle, selfish, calculating |

Anglo-Saxon, vigorous |

The critic Tom Shippey compares Tolkien's characterisation of Gondor with that of Rohan. He notes that men from the two countries meet or behave in contrasting ways several times in The Lord of the Rings: when Éomer and his Riders of Rohan twice meet Aragorn's party in the Mark, and when Faramir and his men imprison Frodo and Sam at Henneth Annun in Ithilien. Shippey notes that while Éomer is "compulsively truculent", Faramir is courteous, urbane, civilised: the people of Gondor are self-assured, and their culture is higher than that of Rohan. The same is seen, Shippey argues, in the comparison between the mead hall of Meduseld in Rohan, and the great hall of Minas Tirith in Gondor. Meduseld is simple, but brought to life by tapestries, a colourful stone floor, and the vivid picture of the rider, his bright hair streaming in the wind, blowing his horn. The Steward Denethor's hall is large and solemn, but dead, colourless, in cold stone. Rohan is, Shippey suggests, the "bit that Tolkien knew best",[20] Anglo-Saxon, full of vigour; Gondor is "a kind of Rome", over-subtle, selfish, calculating.[20]

The critic Jane Chance Nitzsche contrasts the "good and bad Germanic lords Théoden and Denethor", noting that their names are almost anagrams. She writes that both men receive the allegiance of a hobbit, but very differently: Denethor, Steward of Gondor, undervalues Pippin because he is small, and binds him with a formal oath, whereas Théoden, King of Rohan, treats Merry with love, which the hobbit responds to.[21]

In his analysis of the historical lore of Númenor, Michael N. Stanton said close affinities are demonstrated between Elves and the descendants of Men of the West, not only in terms of blood heritage but also in "moral probity and nobility of demeanor", which gradually weakened over time due to "time, forgetfulness, and, in no small part, the machinations of Sauron".[22] The cultural ties between the Men of Gondor and Elves are reflected in the names of certain characters: for instance, Finduilas of Dol Amroth (the wife of Denethor and the sister of Prince Imrahil) shares her name with an Elf princess who lived during the First Age.[23]

Leslie A. Donovan, in A Companion to J. R. R. Tolkien, compares the siege of Gondor with the alliance of Elves and Men in their fight against Morgoth and other co-operative ventures in The Silmarillion, making the point that none of these would have succeeded without collaboration; further that one such success comes from another shared effort, as when the Rohirrim were only able to come to the aid of Gondor because of the joint efforts of Legolas, Gimli, and Aragorn; and that they in turn collaborated with the oathbreakers from the Paths of the Dead.[24]

Influences[]

The scholar of Germanic studies Sandra Ballif Straubhaar notes in The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia that readers have debated the real-world prototypes of Gondor. She writes that like the Normans, their founders the Numenoreans arrived "from across the sea", and that Prince Imrahil's armour with a "burnished vambrace" recalls late-medieval plate armour. Against this theory, she notes Tolkien's direction of readers to Egypt and Byzantium. Recalling that Tolkien located Minas Tirith at the latitude of Florence, she states that "the most striking similarities" are with ancient Rome. She identifies several parallels: Aeneas, from Troy, and Elendil, from Numenor, both survive the destruction of their home countries; the brothers Romulus and Remus found Rome, while the brothers Isildur and Anárion found the Numenorean kingdoms in Middle-earth; and both Gondor and Rome experienced centuries of "decadence and decline".[17]

The scholar of fantasy and children's literature Dimitra Fimi draws a parallel between the seafaring Numenoreans and the Vikings of the Norse world, noting that in The Lost Road and Other Writings, Tolkien describes their ship-burials,[T 55] matching those in Beowulf and the Prose Edda.[25] She notes that Boromir is given a boat-funeral in The Two Towers.[T 56][25] Fimi further compares the helmet and crown of Gondor with the romanticised "headgear of the Valkyries", despite Tolkien's denial of a connection with Wagner's Ring cycle, noting the "likeness of the wings of a sea-bird"[T 57] in his description of Aragorn's coronation, and his drawing of the crown in an unused dust jacket design.[T 58][25]

| Situation | Gondor | Byzantine Empire |

|---|---|---|

| Older state echoed | Elendil's unified kingdom | Roman Empire |

| Weaker sister kingdom | Arnor, the Northern kingdom | Western Roman Empire |

| Powerful enemies to East and South |

Easterlings, Haradrim, Mordor |

Persians, Arabs, Turks |

| Final siege from the East | Survives | Falls |

The classical scholar Miryam Librán-Moreno writes that Tolkien drew heavily on the general history of the Goths, Langobards and the Byzantine Empire, and their mutual struggle. Historical names from these peoples were used in drafts or the final concept of the internal history of Gondor, such as Vidumavi, wife of king Valacar (in Gothic).[26] The Byzantine Empire and Gondor were both, in Librán-Moreno's view, only echoes of older states (the Roman Empire and the unified kingdom of Elendil), yet each proved to be stronger than their sister-kingdoms (the Western Roman Empire and Arnor, respectively). Both realms were threatened by powerful eastern and southern enemies: the Byzantines by the Persians and the Muslim armies of the Arabs and the Turks, as well as the Langobards and Goths; Gondor by the Easterlings, the Haradrim, and the hordes of Sauron. Both realms were in decline at the time of a final, all-out siege from the East; however, Minas Tirith survived the siege whereas Constantinople did not.[26] In a 1951 letter, Tolkien himself wrote about "the Byzantine City of Minas Tirith."[27]

Tolkien visited the Malvern Hills with C. S. Lewis,[28][29] and recorded excerpts from The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings in Malvern in 1952, at George Sayer's home.[30] Sayer wrote that Tolkien relived the book as they walked, comparing the Malvern Hills to the White Mountains of Gondor.[29]

Dimitra Fimi compares Gondor's bird-winged helmet-crown to the romanticised headgear of the Valkyries. Illustration for The Rhinegold and the Valkyrie by Arthur Rackham, 1910[25]

Tolkien called Minas Tirith a "Byzantine City"

(Constantinople shown).[27]The Malvern Hills may have inspired Tolkien to create parts of the White Mountains.[28]

New Zealand's Southern Alps served as Gondor's White Mountains in Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings trilogy.[31]

Adaptations[]

Film[]

Gondor as it appeared in Peter Jackson's film adaptation of The Lord of the Rings has been compared to the Byzantine Empire.[33] The production team noted this in DVD commentary, explaining their decision to include Byzantine domes into Minas Tirith's architecture and to have civilians wear Byzantine-styled clothing.[34] However, the appearance and structure of the city was based upon the inhabited tidal island and abbey of Mont Saint-Michel, France.[32] In the films, the towers of the city, designed by the artist Alan Lee, are equipped with trebuchets.[35] In contrast to the novel's description of the walls of Minas Tirith, the film adaptations depicted the walls as white, and many of them were destroyed with little difficulty by Sauron's forces. The film critic Roger Ebert called the films' interpretation of Minas Tirith a "spectacular achievement", and compared it to the Emerald City from The Wizard of Oz. He praised the filmmakers' ability to blend digital and real sets.[36]

Games[]

The setting of Minas Tirith has appeared in video game adaptations of The Lord of the Rings, such as the 2003 video game The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King where it is directly modelled on Jackson's film adaptation.[37]

Several locations in Gondor were featured in the 1982 role-playing game Middle-earth Role Playing game and its expansions.[38]

Art[]

Christopher Tuthill, in A Companion to J.R.R. Tolkien, evaluates the paintings of Minas Tirith made by the major Tolkien illustrators Alan Lee, John Howe (both of whom worked as conceptual designers for Peter Jackson's film trilogy), Jef Murray, and Ted Nasmith. Tuthill writes that it has become "hard to imagine" Middle-earth "without the many sub-creators who have worked within it", noting that the "dreaded effects" of what Tolkien called "silliness and morbidity" of much fantasy art in his time "are nowhere in evidence" in these artists' work.[39] In Tuthill's view, the most "fully rendered and realistic-looking" painting is Nasmith's Gandalf Rides to Minas Tirith, with a "wholly convincing city" in the background, majestic as the Wizard gallops towards it in the dawn light. He notes that Nasmith uses his architectural rendering skill to provide a detailed view of the whole city.[39] He quotes Nasmith as writing that he studied what Tolkien said, such as likening Gondor to the culture of ancient Egypt. Tuthill compares Howe's and Murray's versions of the same scene; Howe shows only a corner of the city, but vividly captures the movement of the horse and the rider's flying robes, with a strong interplay of light and dark, the white horse against the dusky rocks. Howe similarly uses strong contrast, with the white city against dark clouds overhead, but using "flat bold lines and a deep blue hue", while Howe's city more closely resembles a traditional castle of fairytales with pennants on every pinnacle, in Fauvist style. Lee chooses instead to look Within Minas Tirith, showing "the same glimmering spires and white stone", a guard standing in the foreground in place of Gandalf and his horse; his painting gives a feeling of "how massive the city is", with close attention to the late Romanesque or early Gothic architectural detail and perspective.[39]

Cultural references[]

Dol Amroth is referenced in the name of a rock spire in the Cascade Mountains by visitors who traversed the area west of Mount Buckindy in 1972 and applied a number of names from The Lord of the Rings to local peaks.[40]

Notes[]

- ^ Map #40 in Barbara Strachey's Journeys of Frodo is a plan of Minas Tirith. Fonstad 1991, pp. 138–139 shows a different plan of the city. The only maps by Tolkien are sketches.

- ^ The Tolkien scholar Judy Ann Ford writes that there is also an architectural connection with Ravenna in Pippin's description of the great hall of Denethor, which in her view suggests a Germanic myth of a restored Roman Empire.[8]

- ^ The seal of the stewards consisted of the three letters: R.ND.R (standing for Arandur, king's servant), surmounted by three stars.[T 39]

- ^ Boromir asks his father Denethor how many centuries it would take for a steward to become a king. Denethor replies "Few years, maybe, in other places of less royalty. In Gondor ten thousand years would not suffice."[T 44] Shippey reads this as a reproach to Shakespeare's Macbeth, noting that in Scotland, and in Britain, a Stewart/Steward like James I of England (James VI of Scotland) could metamorphose into a king.[16]

References[]

Primary[]

- This list identifies each item's location in Tolkien's writings.

- ^ a b Return of the King, book 6, ch. 4 "The Field of Cormallen": "a great standard was spread in the breeze, and there a white tree flowered upon a sable field beneath a shining crown and seven glittering stars"

- ^ a b Return of the King, Appendix F, "Of Men"

- ^ Etymologies, entries GOND-, NDOR-

- ^ a b Return of the King, book 5 ch. 6 "The Battle of the Pelennor Fields"

- ^ Return of the Shadow, ch. 22 "New Uncertainties and New Projections"

- ^ a b Return of the King, book 5 ch. 5 "The Ride of the Rohirrim"

- ^ Carpenter 1981, #324

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R.; Gilson, Christopher (editing, annotations). "Words, Phrases and Passages in Various Tongues in The Lord of the Rings". Parma Eldalamberon (17): 101.

- ^ The Return of the King, "The Tower of Cirith Ungol"

- ^ Etymologies, entries ÁNAD-, PHÁLAS-, TOL2-

- ^ a b c d Return of the King, book 5 ch. 1 "Minas Tirith"

- ^ a b c Unfinished Tales, part 2 ch. 4 "History of Galadriel and Celeborn": "Amroth and Nimrodel"

- ^ a b Return of the King, book 5 ch. 9 "The Last Debate"

- ^ a b Unfinished Tales, map of the West of Middle-earth

- ^ Peoples, ch. 6 "The Tale of Years of the Second Age"

- ^ Fonstad 1991, p. 191

- ^ Peoples, ch. 10 "Of Dwarves and Men", and notes 66, 76

- ^ a b c d e f Return of the King, Appendix A, I (iv)

- ^ Unfinished Tales, part 2 ch. 4 "History of Galadriel and Celeborn"; Appendices C and D

- ^ a b c Unfinished Tales, "The Battles of the Fords of Isen", Appendix (ii)

- ^ a b Return of the King, book 1 ch. 2 "The Passing of the Grey Company"

- ^ Return of the King, map of Gondor

- ^ Fonstad 1991, pp. 83–89

- ^ The Return of the King, book 5 ch. 8 "The Houses of Healing"

- ^ a b c The Return of the King, book 5, ch. 4 "The Siege of Gondor"

- ^ Unfinished Tales, "Cirion and Eorl and the Friendship of Gondor and Rohan".

- ^ The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, Introduction and Poem 6

- ^ Letters, #244 to a reader, draft, c. 1963

- ^ The Lord of the Rings, Appendix A, "The Stewards"

- ^ Unfinished Tales, "Disaster of the Gladden Fields".

- ^ The Lord of the Rings, Appendix A, "The House of Eorl"

- ^ The Return of the King, "Minas Tirith"

- ^ Return of the King, book 5 ch. 8 "The Houses of Healing

- ^ The Return of the King, "Minas Tirith"

- ^ Return of the King, book 6 ch. 6 "Many Partings"

- ^ Return of the King, Appendix F part 1

- ^ a b c d e Silmarillion, "Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age"

- ^ a b Unfinished Tales, part 3 ch. 1 "Disaster of the Gladden Fields"

- ^ a b Unfinished Tales & see note 25, part 3 ch. 2 "Cirion and Eorl"

- ^ a b c d e Return of the King, Appendix B "The Third Age"

- ^ a b Peoples, ch. 7 "The Heirs of Elendil"

- ^ a b Unfinished Tales, part 3 ch. 2 "Cirion and Eorl", (i)

- ^ Return of the King, book 5 ch. 8 "The Houses of Healing"; book 6 ch. 5 "The Steward and the King"

- ^ a b Two Towers, book 4, ch. 5 "The Window on the West"

- ^ Fellowship of the Ring, book 2 ch. 2 "The Council of Elrond"

- ^ Two Towers, book 4 ch. 5 "The Window on the West"

- ^ Return of the King, Appendix A, II

- ^ Peoples, ch. 8 "The Tale of Years of the Third Age"

- ^ Carpenter 1981, #256, #338

- ^ Lost Road, ch. 2 "The Fall of Númenor"

- ^ Peoples, ch. 9 "The Making of Appendix A". Letter c in names is used for original k.

- ^ Peoples, ch. 13 "Last Writings"

- ^ a b c d e f Unfinished Tales, part 2 ch. 4 "History of Galadriel and Celeborn"

- ^ Unfinished Tales, "Aldarion and Erendis".

- ^ The Lost Road and Other Writings, ch. 2 "The Fall of Numenor"

- ^ Two Towers, book 3, ch. 1 "The Departure of Boromir"

- ^ Return of the King, book 6, ch. 5 "The Steward and the King"

- ^ The Winged Crown of Gondor. Bodleian Library, Oxford, MS. Tolkien Drawings 90, fol. 30.

Secondary[]

- ^ Hammond & Scull 2005, "The Great River", p. 347

- ^ Noel, Ruth S. (1974). The Languages of Tolkien's Middle-earth. Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 170. ISBN 0-395-29129-1.

- ^ a b c Garth, John (2020). The Worlds of J.R.R. Tolkien: The Places that Inspired Middle-earth. Frances Lincoln Publishers & Princeton University Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-7112-4127-5.

- ^ a b Drieshen, Clark (31 January 2020). "The Trees of the Sun and the Moon". British Library. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ^ Gasse, Rosanne (2013). "The Dry Tree Legend in Medieval Literature". In Gusick, Barbara I. (ed.). Fifteenth-Century Studies 38. Camden House. pp. 65–96. ISBN 978-1-57113-558-2.

Mandeville also includes a prophecy that when the Prince of the West conquers the Holy Land for Christianity, this tree will become green again, rather akin to the White Tree of Arnor [sic] in the Peter Jackson film version of The Lord of the Rings, if not in Tolkien's original novel, which sprouts new green leaves when Aragorn first arrives in Gondor at [sic, i.e. after] the Battle of the Pelennor Fields.

- ^ Flood, Alison (23 October 2015). "Tolkien's annotated map of Middle-earth discovered inside copy of Lord of the Rings". The Guardian.

- ^ "Tolkien annotated map of Middle-earth acquired by Bodleian library". Exeter College, Oxford. 9 May 2016. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ Ford, Judy Ann (2005). "The White City: The Lord of the Rings as an Early Medieval Myth of the Restoration of the Roman Empire". Tolkien Studies. 2 (1): 53–73. doi:10.1353/tks.2005.0016. ISSN 1547-3163. S2CID 170501240.

- ^ Foster, Robert (1978). A Guide to Middle-earth. Ballantine Books. p. 60. ISBN 978-0345275479.

- ^ a b Viars, Karen (2015). "Constructing Lothiriel: Rewriting and Rescuing the Women of Middle-Earth From the Margin". Mythlore. 33. article 6.

- ^ Honegger, Thomas (2017). "Riders, Chivalry, and Knighthood in Tolkien". Journal of Tolkien Research. 4. article 3.

- ^ Davis, Alex (2013) [2006]. "Boromir". In Michael D.C. Drout (ed.). The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 412-413. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- ^ Hammond & Scull 2005, "The Great River", pp. 683–684

- ^ Armstrong, Helen (2013) [2006]. "Arwen". In Michael D.C. Drout (ed.). The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 38-39. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- ^ ref>Foster, Robert (1978). The Complete Guide to Middle-earth. Ballantine Books. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-345-44976-4.

- ^ Shippey 2005, p. 206.

- ^ a b c Straubhaar 2007, pp. 248–249.

- ^ a b O'Connor, David (2017). "For What May We Hope? An Appreciation of Peter Simpson's Political Illiberalism". The American Journal of Jurisprudence. 62 (1): 111–117. doi:10.1093/ajj/aux014.

- ^ De Rosario Martínez, Helios (November 22, 2005). "Light and Tree A Survey Through the External History of Sindarin". Elvish Linguistic Fellowship.

- ^ a b c d Shippey 2005, pp. 146–149.

- ^ Nitzsche 1980, pp. 119–122.

- ^ Stanton, Michael (2015). Hobbits, Elves and Wizards: The Wonders and Worlds of J.R.R. Tolkien's "Lord of the Rings". St. Martin's Publishing Group. p. Pt 143. ISBN 978-1-2500-8664-8.

- ^ Day, David (1993). Tolkien: The Illustrated Encyclopaedia. Simon and Schuster. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-6848-3979-0.

- ^ Donovan, Leslie A. (2020) [2014]. "Middle-earth Mythology: An Overview". In Lee, Stuart D. (ed.). A Companion to J. R. R. Tolkien. Wiley. p. 100. ISBN 978-1119656029.

- ^ a b c d Fimi 2007, pp. 84–99.

- ^ a b c Librán-Moreno, Miryam (2011). "'Byzantium, New Rome!' Goths, Langobards and Byzantium in The Lord of the Rings". In Fisher, Jason (ed.). Tolkien and the Study of his Sources. MacFarland & Co. pp. 84–116. ISBN 978-0-7864-6482-1.

- ^ a b Hammond & Scull 2005, p. 570

- ^ a b Duriez 1992, p. 253

- ^ a b Sayer 1979

- ^ Carpenter 1977

- ^ "Lord Of The Rings: The Return Of The King: 2003". Movie Locations. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

Ben Ohau Station, in the Mackenzie Basin, in the Southern Alps, ... provided the ‘Pelennor Fields’, and the foothills of the ‘White Mountains’, for the climactic battle scenes

- ^ a b Morrison, Geoffrey (27 June 2014). "The real-life Minas Tirith from 'Lord of the Rings': A tour of Mont Saint-Michel". CNET.

- ^ Puig, Claudia (24 February 2004). "With third film, 'Rings' saga becomes a classic". USA Today.

In the third installment, for example, Minas Tirith, a seven-tiered city of kings, looks European, Byzantine and fantastical at the same time.

- ^ The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (special extended DVD ed.). December 2004.

- ^ Russell, Gary (2004). The Art of The Lord of the Rings. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 103–105. ISBN 0-618-51083-4.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (17 December 2003). "Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 11 December 2011. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ Dobson, Nina (28 October 2003). "The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King Designer Diary #6". GameSpot. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ^ "Assassins of Dol Amroth". RPGnet. Skotos. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ a b c Tuthill, Christopher (2020) [2014]. "Art: Minas Tirith". In Lee, Stuart D. (ed.). A Companion to J.R.R. Tolkien. Wiley. pp. 495–500. ISBN 978-1119656029.

- ^ Beckey, Fred W. (2003). Cascade Alpine Guide: Climbing and High Routes, Stevens Pass to Rainy Pass. The Mountaineers Books. p. 287. ISBN 9780898868388.

Sources[]

- Carpenter, Humphrey (1977), J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biography, New York: Ballantine Books, ISBN 978-0-04-928037-3

- Duriez, Colin (1992). The J.R.R. Tolkien handbook. Baker Book House. p. 253. ISBN 0801030145.

- Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (1981), The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 978-0-395-31555-2

- Fimi, Dimitra (2007). Clark, David; Phelpstead, Carl (eds.). Tolkien and Old Norse Antiquity (PDF). Old Norse Made New: Essays on the Post-Medieval Reception of Old Norse Literature and Culture. Viking Society for Northern Research: University College London. pp. 84–99. S2CID 163015967. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-02-26.

- Fonstad, Karen Wynn (1991), The Atlas of Middle-earth, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, ISBN 0-618-12699-6

- Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina (2005), The Lord of the Rings: A Reader's Companion, London: HarperCollins, ISBN 0-00-720907-X

- Nitzsche, Jane Chance (1980) [1979]. Tolkien's Art. Papermac. ISBN 0-333-29034-8.

- Sayer, George (1979) [August 1952 recording]. "Liner notes". J.R.R. Tolkien Reads and Sings his 'The Hobbit' and 'The Fellowship of the Ring'. Caedmon.

- Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). Grafton (HarperCollins). ISBN 978-0261102750.

- Straubhaar, Sandra Ballif (2007). "Gondor". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge. pp. 248–249. ISBN 978-0-415-96942-0.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954), The Fellowship of the Ring, The Lord of the Rings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, OCLC 9552942

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954), The Two Towers, The Lord of the Rings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, OCLC 1042159111

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1955), The Return of the King, The Lord of the Rings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, OCLC 519647821

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1977), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The Silmarillion, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 978-0-395-25730-2

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1980), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), Unfinished Tales, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 978-0-395-29917-3

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1987), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The Lost Road and Other Writings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, The Etymologies, pp. 341–400, ISBN 0-395-45519-7

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1988), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The Return of the Shadow, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 978-0-395-49863-7

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1996), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The Peoples of Middle-earth, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 978-0-395-82760-4

Further reading[]

- Ford, Judy Ann (2005). "The White City: The Lord of the Rings as an Early Medieval Myth of the Restoration of the Roman Empire". Tolkien Studies. 2: 53–73. doi:10.1353/tks.2005.0016. S2CID 170501240.

- Straubhaar, Sandra Ballif (2004). "Myth, Late Roman History and Multiculturalism in Tolkien's Middle-earth". In Chance, Jane (ed.). Tolkien and the Invention of Myth: A Reader. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 101–118. ISBN 0-8131-2301-1.

- Fictional elements introduced in 1954

- Middle-earth realms

- Middle-earth rulers

- Middle-earth populated places

- Fictional kingdoms