Mongol invasions of Vietnam

This second invasion may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (July 2021) |

| Mongol invasions of Đại Việt and Champa | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mongol invasions and Kublai Khan's campaigns | |||||||

Mongol conquests | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Mongol Empire (1258) Yuan dynasty (1283–85 and 1287–88) | Đại ViệtChampaChinese exiles and deserters | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Möngke KhanKublai KhanUriyangkhadai Aju † † Toghon[1] (POW) Abachi † Fan Yi |

Trần Thái Tông Trần Thánh Tông Trần Nhân Tông Trần Hưng Đạo Trần Quang Khải Trần Quốc Toản † Trần Bình Trọng † Trần Ích Tắc | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

First invasion (1258): ~3,000 Mongols 10,000 Yi people (Western estimate)[2]~30,000 Mongols 2,000 Yi people (Vietnamese estimate)[3]Second invasion (1285): ~80,000–300,000 (some speak of 500,000) in March 1285[4]Third invasion (1288): Remaining forces from the second invasion,Reinforcements: 70,000 Yuan troops 21,000 tribal auxiliaries 500 ships[5]Total: 170,000[6] |

Second invasion of Champa and Đại Việt (1283–1285): 30,000 Chams[7]c. 100,000 Vietnamese[8] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1285: 50,000 captured[9]1288: 90,000 killed or drowned[10] | Unknown | ||||||

The Mongol invasions of Vietnam or Mongol–Vietnamese wars and Mongol–Cham war were military campaigns launched by the Mongol Empire, and later the Yuan dynasty, against the kingdom of Đại Việt (modern-day northern Vietnam) ruled by the Trần dynasty and the kingdom of Champa (modern-day central Vietnam) in 1258, 1282–1284, 1285, and 1287–88. The campaigns are treated by a number of scholars as a success due to the establishment of tributary relations with Đại Việt despite the Mongols suffering major military defeats.[11][12][13] In contrast, Vietnamese historiography regards the war as a major victory against the foreign invaders who they called "the Mongol yokes."[14][11]

The first invasion began in 1258 under the united Mongol Empire, as it looked for alternative paths to invade the Song dynasty. The Mongol general Uriyangkhadai was successful in capturing the Vietnamese capital Thang Long (modern-day Hanoi) before turning north in 1259 to invade the Song dynasty in modern-day Guangxi as part of a coordinated Mongol attack with armies attacking in Sichuan under Möngke Khan and other Mongol armies attacking in modern-day Shandong and Henan.[15] The first invasion also established tributary relations between the Vietnamese kingdom, formerly a Song dynasty tributary state, and the Yuan dynasty. In 1282, Kublai Khan and the Yuan dynasty launched a naval invasion of Champa that also resulted in the establishment of tributary relations.

Intending to demand greater tribute and direct Yuan oversight of local affairs in Đại Việt and Champa, the Yuan launched another invasion in 1285. The second invasion of Đại Việt failed to accomplish its goals, and the Yuan launched a third invasion in 1287 with the intent of replacing the uncooperative Đại Việt ruler Trần Nhân Tông with the defected Trần prince Trần Ích Tắc. By the end of the second and third invasions, which involved both initial successes and eventual major defeats for the Mongols, the Đại Việt and Champa decided to accept the nominal supremacy of the Yuan dynasty and serve as tributary states in order to avoid further conflicts.[16][17]

Background[]

By the 1250s, the Mongol Empire controlled large amounts of Eurasia including much of Eastern Europe, Anatolia, North China, Mongolia, Manchuria, Central Asia, Tibet and Southwest Asia. Möngke Khan (r. 1251–59) planned to attack the Song dynasty in southern China from three directions in 1259. Therefore, he ordered the prince Kublai to pacify the Dali Kingdom.[18] Uriyangkhadai led successful campaigns in the southwest of China and pacified tribes in Tibet before turning east towards Đại Việt by 1257.[19]

The conquest of Yunnan[]

To avoid a costly frontal assault on the Song, which would have required a risky forced crossing of the lower Yangtze, Mongke decided to establish a base of operations in southwestern China, from which a flank attack could be staged.[18] In the late summer of 1252 he ordered his brother Kublai to lead the southwest campaign. In fall, the Mongol armies advanced to the Tao River, then penetrated the Szechwan basin, defeated a Song army and established a major base in Sichuan.[18] Total Mongol forces raised up to 100,000 men.[20]

When Mongke learned that the king of Dali in Yunnan (a kingdom ruled by the Tuan dynasty) refused to negotiate, and his prime minister had murdered the envoys whom Mongke had sent to Dali to demand the king's surrender, he ordered Kublai and Uriyangkhadai attack Dali in summer 1253.[21] In September, Kublai launched a three-pronged attack on Dali.[20] The western army led by Uriyangkhadai, marched from modern-day Gansu through eastern Tibet toward Dali; the eastern army led by marched southward from Sichuan, passed just west of Chengdu before reuniting briefly with Kublai's army in the town of Xichang. Kublai's army met and engaged with Dali forces along the Jinsha River.[21] After several skirmishes in which Dali forces repeatedly turned back the Mongol raids, Kublai's army crossed the river on inflated rafts of sheepskin during a night and routed Dali defensive positions.[22] With Dali forces in disarray, three Mongol columns quickly captured the capital of Dali on December 15, 1253, and even though its ruler had rejected Kublai's submission order, the capital and its inhabitants were spared.[23] Duan Xingzhi and Gao Xiang both fled, but Gao was soon captured and beheaded.[24] Duan Xingzhi fled to Shanchan (modern-day Kunming) and continued to resist the Mongols with aids from local clans until autumn 1255 when he was finally captured.[24] As they had done on many other invasions, the Mongols left the native dynasty in place under the supervision of Mongolian officials.[25] Bin Yang noted that the Duan clan was recruited to assist with further invasions of the Burmese Pagan Empire and the initial successful attack on the Vietnamese kingdom of Dai Viet.[24]

At the end of 1254, Kublai returned to Mongolia to consult with his brother about the khagan title. Uriyangkhadai was left in Yunnan, and from 1254 to 1257 he conducted campaigns against local Yi and Lolo tribes. In early 1257 he returned to Gansu and sent emissaries to Mongke's court informing his sovereign that Yunnan was now firmly under Mongolian control. Pleased, the emperor honored and generously rewarded Uriyangkhadai for his fine achievement.[25] Then Uriyangkhadai subsequently returned to Yunnan and began preparing for the first Mongolian incursions into Southeast Asia.[25]

The Dai Viet kingdom or Annam, emerged in 960s as the Vietnamese had been carved up their territories in northern Vietnam (the Red River Delta) from the local Tang remnant regime since the fall of the Tang empire in 907. The kingdom had been gone through four dynasties, both kept a regulating peaceful tributary relationship with the Chinese Song empire. In the autumn of 1257, Uriyangkhadai sent two envoys to the Vietnamese ruler Trần Thái Tông (known as Trần Nhật Cảnh by the Mongol) asking a submission and a passage to attack the Song from the south.[26] Trần Thái Tông opposed the encroachment of a foreign army across his territory to attack their ally, therefore the envoys were imprisoned,[27] and so prepared soldiers on elephants to deter the Mongol troops.[28] After the three successive envoys were imprisoned in the capital Thang Long (modern-day Hanoi) of Đại Việt, Uriyangkhadai invaded Đại Việt with generals Trechecdu and Aju in the rear.[29][2]

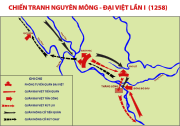

First Mongol invasion in 1258[]

Mongol forces[]

In early 1258, a Mongol column under Uriyangkhadai, the son of Subutai, invaded Đại Việt. According to Vietnamese sources, the Mongol army consisted of at least 30,000 soldiers of which at least 2,000 were Yi troops from the Dali Kingdom.[3] Modern scholarship points to a force of several thousand Mongols, ordered by Kublai to invade with Uriyangkhadai in command, which battled with the Viet forces on 17 January 1258.[30] Some Western sources estimated that the Mongol army consisted of about 3,000 Mongol warriors with an additional 10,000 Yi soldiers.[2]

Campaign[]

A battle was fought in which the Vietnamese used war elephants: king Trần Thái Tông even led his army from atop an elephant.[31] Aju ordered his troops to fire arrows at the elephants' feet.[31][28] The animals turned in panic and caused disorder in the Vietnamese army, which was routed.[31][28]The Vietnamese senior leaders were able to escape on pre-prepared boats while part of their army was destroyed at No Nguyen (modern Viet Tri on the Hong River). The remainder of the Dai Viet army again suffered a major defeat in a fierce battle at the Phú Lộ bridge the day after. This led the Vietnamese monarch to evacuate the capital. The Đại Việt annals reported that the evacuation was "in an orderly manner;" however this is viewed as an embellishment because the Vietnamese had to retreat in disarray to leave their weapons behind in the capital.[31]

King Trần Thái Tông fled to an offshore island,[32][25] while the Mongols occupied the capital city Thăng Long (modern-day Hanoi). They found their envoys in prison, with one of them already deceased. In revenge, Mongols massacred the city's inhabitants.[27] Although the Mongols had successfully captured the capital, the provinces around the capital were still under Vietnamese control.[31] While Chinese source material is sometimes misinterpreted as saying that Uriyangkhadai withdrew from Vietnam due to poor climate,[33][15] Uriyangkhadai left Thang Long after nine days to invade the Song dynasty in modern-day Guangxi in a coordinated Mongol attack with armies attacking in Sichuan under Möngke Khan and other Mongol armies attacking in modern-day Shandong and Henan.[15] The Mongol army gained the popular local nickname of "Buddhist enemies" because they did not loot nor kill while moving north out to Yunnan.[34] After the loss of a prince and the capital, Trần Thái Tông submitted to the Mongols.[28]

In 1258, the Vietnamese monarch Trần Thái Tông commenced regular diplomatic relations and a tributary relationship with the Mongol court, treating them as equals to the embattled Southern Song dynasty without renouncing their ties to the Song.[35] In March 1258, Trần Thái Tông retired and let his son, prince Trần Hoảng, succeed the throne. In the same year, the new king sent envoys to the Mongol in Yunnan. The Mongol leader Uriyangkhadai demanded that the king come to China to submit in person. King Trần Thánh Tông answer: "If my small country sincerely serves your majesty, how will your big country treat us?" The Mongol envoys traveled back to Thăng Long, Yunnan and Dadu, eventually the message from the Vietnamese court was that the king's children or brother would be sent to China as hostage.[27][25]

Invasion of Champa in 1282[]

Background and diplomacy[]

With the defeat of the Song dynasty in 1276, the newly established Yuan dynasty turned its attention to the south, particularly Champa and Đại Việt.[36] Kublai was interested in Champa because, by geographical location, it dominated the sea routes between China and the states of Southeast and India.[36] Champa at the time was the economic superpower in Southeast Asia. Although the king of Champa accepted the status of a Mongol protectorate,[37] his submission was unwilling. In late 1281, Kublai issued the edict ordering the mobilization of a hundred ships and ten thousand men, consisting of official Yuan forces, former Song troops and sailors to invade Sukhothai, Lopburi, Malabar and other countries, and Champa "will be instructed to furnish the food supplies of the troops."[38] However, his plans were canceled as the Yuan court discussed that they would send envoys to these countries to make them submit to the Yuan. This suggestion was adopted and successful for the Yuan, but these missions all had to pass by or stop at Champa. Kublai knew that the pro-Song sentiment was strong in Champa, as the Cham king had been sympathetic to the Song cause.[38]

A large numbers of Chinese officials, soldiers and civilians who fled from the Mongol had been refugees in Champa, and they had inspired and incited to hate the Yuan.[39] Thus, in the summer of 1282, when Yuan envoys He Zizhi, Hangfu Jie, Yu Yongxian, and Yilan passed through Champa, they were detained and imprisoned by the Cham Prince Harijit.[39] In summer 1282, Kublai ordered of the Jalairs, the governor of Guangzhou, to lead the punitive expedition to the Chams. Kublai declared: "The old king (Jaya Indravarman V) is innocent. The ones who oppose to our order was his son (Harijit) and a Southern Chinese."[39] In late 1282, Sogetu led a maritime invasion of Champa with 5,000 men, but could only muster 100 ships and 250 landing crafts because most of the Yuan ships had been lost in the invasions of Japan.[40]

Campaign[]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Sogetu's fleet arrived in Champa's shore, near modern-day in February 1283.[41] The Cham defenders had already prepared a fortified wooden palisades on the west shore of the bay.[39] The Mongol landed at midnight of 13 February, attacked the stockade by three sides. The Cham defenders opened the gate, marched to the beach and met the Yuan with 10,000 men and several scores of elephants.[7] Undaunted, the highly experienced Mongol general selected points of attack and launched so fierce an assault that they broke through.[41] The Yuan eventually routed their enemy and captured Cham forts and their vast supplies. Sogetu arrived in the Cham capital Vijaya and captured the city two days later, but then withdrew and set up camps outside the city.[7] The aged Champa king Indravarman V abandoned his temporary headquarter (palace), had set fire to his warehouses and retreated out of the capital, avoiding Mongol attempts to capture him in the hills.[7] The Cham king and his prince Harijit both refused to visit the Yuan camp. The Cham executed two captured Yuan envoys and ambushed Sogetu's troops in the mountains.[7]

As the Cham delegates continued to offer excuses, the Yuan commanders gradually began to realize that the Chams had no intention of coming to terms and were only using the negotiations to stall for time.[7] From a captured spy, Sogetu knew that Indravarman had 20,000 men with him in the mountains, he had summoned Cham reinforcements from Panduranga (Phan Rang) in the south, and also dispatched emissaries to Đại Việt, Khmer Empire and Java for seeking aid.[42] On 16 March, Sogetu sent a strong force into the mountains to seek and destroy the hideout of the Cham king. It was ambushed and driven back with heavy losses.[43] His son would wage guerrilla warfare against the Yuan for the next two years, eventually wearing down the invaders.[44]

The Yuan withdrew to the wooden stockade on the beach in order to await reinforcements and supplies. Sogetu's men unloaded the supplies, cleared the field for farming rice so he was able to harvest 150,000 piculs of rice in that summer.[43] Sogetu sent two officers to threaten the king of Khmer Empire Jayavarman VIII, but they were detained.[43] Stymied by the withdrawal of the Champa king, Sogetu asked for reinforcement from Kublai. In March 1284 another Yuan fleet with more than 20,000 troops of 200 ships under and Ariq Qaya anchored the coast of Vijaya. Sogetu presented his plan to have reinforcements to invade Champa marching through the vassalised Đại Việt. Kublai accepted his plan and put his son Toghan in command, with Sogetu as second in command.[43]

Second Mongol invasion in 1285[]

Interlude (1260–1284)[]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

In 1261, the Vietnamese king Trần Thánh Tông (son of Trần Thái Tông – known to the Mongols as Trần Nhật Huyên) agreed to acknowledge the overlordship of Kublai Khan, and sent tributary envoys to Dadu. Kublai enfeoffed Trần Thánh Tông as "King of Annam" (Annan guowang).[45] However in 1267, he rejected the "Six-Duties of a vassal state" of the Mongol Emperor gave, included the permit the stationing of a darughachi (regional general) with authority over the local administration.[32] Kublai Khan was dissatisfied with the tributary arrangement, which granted the Yuan dynasty the same amount of tribute as the former Song dynasty had received, and requested greater tributary payments.[35] These demands included taxes to the Mongols in both money and labor, "incense, gold, silver, cinnabar, agarwood, sandalwood, ivory, tortoiseshell, pearls, rhinoceros horn, silk floss, and porcelain cups".[35] Later that year, Kublai required that the Đại Việt court send two Muslim merchants he believed to be in Đại Việt to China in order for them to serve on missions on the Western regions and designated heir apparent of the Yuan as "Prince of Yunnan" to take control of Dali, Shanshan (Kunming) and Đại Việt. This would mean that Đại Việt should be incorporated into the Yuan Empire, which was totally unacceptable to the Vietnamese.[46] In 1274, Chinese refugees from Southern Song fled in 30 boats to Dai Viet.[47]

In 1278, Trần Thái Tông died, the king Trần Thánh Tông retired and made crown prince Trần Khâm (as known as Trần Nhân Tông, known to the Mongol as Trần Nhật Tôn) his successor. Kublai sent a mission led by Chai Chun to Đại Việt, one again urged the new king to come to China in person, however the Yuan mission ended in failures as the king resisted to go.[48] The Yuan then refused to recognize him as king and tried to place a Vietnamese defector as king of Dai Viet.[47] Frustrated with these failed diplomat missions, many Yuan officials urged Kublai to send a punitive expedition to Đại Việt.[49] In 1283, Khubilai Khan sent Ariq Qaya to Dai Viet with an imperial request for help from Annam (Dai Viet) to attack Champa through Vietnamese territory, with demands for provisions and other support to the Yuan army.[50][35]

In 1284 Kublai appointed his son Toghan to command a force overland to assist Sogetu. Toghan demanded from the Vietnamese a route to Champa, which would trap the Cham army from both north and south, but they refused, and came to the conclusion that this was a pretext for a Yuan conquest of Dai Viet. Nhân Tông ordered a defensive war against the Yuan invasion, with Prince Trần Quốc Tuấn in charge of the army.[51] A Yuan envoy recorded that the Vietnamese had already sent 500 ships to help the Cham.[52] In fall 1284 Toghon moved his troops to the border with Dai Viet, and in December a envoy reported that Kublai had ordered Toghon, Pingzhang Ali and Ariq Qaya to enter Dai Viet under the banner to attack Champa, but instead to invade Dai Viet.[50] Southern Song Chinese military officers and civilian officials left to overseas countries, went to Vietnam and intermarried with the Vietnamese ruling elite and went to Champa to serve the government there as recorded by Zheng Sixiao.[45] Southern Song soldiers were part of the Vietnamese army prepared by king Trần Thánh Tông against the second Mongol invasion.[53] Also in the same year, the Venetian traveler Marco Polo might have visited Dai Viet (Caugigu)[a] almost when the Yuan and the Vietnamese were ready for war, then he went to Chengdu via Heni (Amu).[55]

War[]

Mongol advance (January – May 1285)[]

The land Yuan army invading Dai Viet under the command of prince Toghon and Uighur general Ariq Qaya, while Tangut general Li Heng and Muslim general Omar led the navy.[56] The Vietnamese forces, were reported numbering 100,000.[8] Yuan troops crossed the Friendship Pass (Sino-Vietnamese border's gate) on 27 January 1285, divided in six columns while working their way down the rivers.[8] After passing the mountainous terrain, while collecting nails and other traps along the highway, Mongol forces under Omar reached Vạn Kiếp (modern-day Hải Dương province) on 10 February, and three days later they broke the Vietnamese defenses to reach the north bank of Cầu River.[8] On 18 February the Mongols used captured boats and defeated the Vietnamese, successfully crossing the river. All prisoners caught to have the words "Sát Thát" tattooed on their arms were executed. Instead of advancing further south after their victory, the Yuan forces remained kin the north bank of the river, fighting daily skirmishes but making little advances to the Vietnamese in the south.[8]

In a pincer movement, Toghon sent an officer name Tanggudai to instruct Sogetu, who was in Huế to march north while at the same time he was sending frantic appeals for reinforcements from China, and he wrote to the Vietnamese king that the Yuan forces had come in, not as enemies but as allies against Champa.[8] In late February, Sogetu's forces marching from the south penetrated the pass of Nghệ An, capturing the cities of Vinh and Thanh Hoá, as well as the Vietnamese supply bases in Nam Định and Ninh Bình, as well as taking prisoner 400 Song officers who were fighting alongside with the Vietnamese. Prince Quốc Tuấn divided his forces in an effort to prevent Sogetu from grouping with Toghon, but this effort failed and he was overwhelmed.[56]

In late February, Toghon launched a full offensive against Dai Viet. A Yuan fleet under the command of Omar attacked along the Đuống River, succeeding in capturing Thang Long while driving king Nhân Tông to the sea.[56] Planning to weaken the Yuan's strength, the Vietnamese abandoned the capital and retreated south while enacting a scorched earth campaign by abandoning empty capital and cities, burning villages and crops where the Yuan occupied.[44] The following day, Toghon entered the capital and found naught but an empty palace.[57] Many Vietnamese royals and nobles were frightened and defected to the Yuan, including prince Trần Ích Tắc.[58] The king Trần Nhân Tông and his army managed to escape to his royal estates in Nam Định, and re-concentrated there.[51] The Yuan forces under Omar launched two naval offensives in April and again drove the Vietnamese forces to the south.[56]

Vietnamese counterattack (May – June 1285)[]

In May 1285, the situation began changing as the Yuan had overextended their supply network, Toghon ordered Sogetu to lead his troops attack Nam Định (the main Vietnamese bases) to seize supplies.[59] In Thăng Long, the situation of the Yuan forces grew desperate. Shortage of food, starvation, summer heat and disease began draining both manpower and morale. Mongol and Turkic heavy cavalry units were insufficient in such hostile environments which proved only suitable for infantry and naval forces. In a battle in Hàm Tử pass (modern-day Khoái Châu District, Hưng Yên) in late May 1285, a contingent of Yuan troops was defeated by a partisan force consisting of former Song troops led by Zhao Zhong under prince Nhật Duật and native militia.[58] On 9 June 1285, Mongol troops evacuated Thang Long to retreat back to China.[59]

Taking advantage, the Vietnamese force under prince Quốc Tuấn sailed to the north and attacked Vạn Kiếp, the important Yuan camp and further severed Yuan supplies.[60] Many Yuan generals were killed in the battle, among them the senior Li Heng, who was struck by a poisoned arrow.[6] The Yuan forces collapsed into disarray, and Sogetu was killed in Chương Dương by a joint Cham-Vietnamese force in June 1285.[61] To protect Toghon from being shot, the soldiers made a copper box in which they hid him until they were able to retreat to the Guangxi border.[62] Yuan generals Omar and Liu Gui ran to the beach, found a small boat and escaped back to China. The Yuan remnants retreated back to China on late June 1285 as the Vietnamese king and royals returned to the capital in Thăng Long following the six month conflict..[62][63]

Third Mongol invasion in 1287–1288[]

Background and preparations[]

In 1286, Kublai Khan appointed Trần Thánh Tông's younger brother, Prince Trần Ích Tắc, as the King of Đại Việt from afar with the intent of dealing with the uncooperative incumbent Trần Nhân Tông.[64][65] Trần Ích Tắc, who had already surrendered to the Yuan, was willing to lead a Yuan army into Đại Việt to take the throne.[64] Kublai Khan cancelled plans underway for a third invasion of Japan to concentrate military preparations in the south.[66] Kublai accused the Vietnamese of raiding China, and pressed the efforts of China should be directed towards winning the war against Đại Việt.[67]

In October 1287, the Yuan land forces commanded by Toghon (assisted by Nasir al-Din and Kublai's grandson Esen-Temür)[9] moved southwards from Guangxi and Yunnan in three divisions led by general Abachi and Changyu,[68] while the naval expedition led by generals Omar, Zhang Wenhu, and Aoluchi.[64] The army was complemented by a large naval force that advanced from Qinzhou, with the intent to form a large pincer movement against the Vietnamese.[64] The force was composed of 70,000 Mongols, Jurchen, Han Chinese from Jiangsu, Jiangxi, Hunan, and Guangdong; 6,000 Yunnanese troops; 1,000 former Song troops; 17,000 Li troops from Hainan; and 18,000 crewmen.[68] Total Yuan forces raised up to 170,000 men for this invasion.[6]

Campaign[]

The Yuan were successful in the early phases of the invasion, occupying and looting the Đại Việt capital.[64]

In January 1288, as Omar's fleet passed through the Ha Long Bay to join Toghon's forces in Vạn Kiếp (modern-day Hải Dương province), followed by Zhang Wenhu's supply fleet, the Vietnamese navy under prince Trần Khánh Dư attacked and destroyed Wenhu's fleet.[69][66] The Yuan land army under Toghan and naval fleet under Omar, both already in Vạn Kiếp, were unaware of the loss of their supply fleet.[69] Despite that, in February 1288 Toghon ordered to attack the Vietnamese forces. Toghon returned to the capital Thăng Long to loot food, while Omar destroyed king Trần Thái Tông's tomb in Thái Bình.[66]

Due to a lack of food supplies, Toghon and Omar's army retreated from Thăng Long to their fortified main base in Vạn Kiếp (northeast of Hanoi) on 5 March 1288. [70] They planned to withdraw from Đại Việt but waited for the supplies to arrive before departing.[69] As food supplies ran low and their positions became untenable, Toghon decided on 30 March 1288 to return to China.[70] Toghon boarded a large warship for himself and the Yuan land force could not withdraw in the same way from which they came. Trần Hưng Đạo, aware of the Yuan retreat, prepared to attack. The Vietnamese had destroyed bridges and roads and created traps along the retreating Yuan route. They pursued Toghon's forces to Lạng Sơn, where on April 10,[10] Toghon himself was struck by a poisoned arrows,[1] and was forced to abandon his ship and avoided highways as he was escorted back to Siming in China by his few remaining troops through the forests.[10] Most of Toghon's land force were killed or captured.[10] Meanwhile, the Yuan fleet commanded by Omar were retreating through the Bạch Đằng river.[70]

At the Bạch Đằng River in April 1288, the Vietnamese prince Trần Hưng Đạo ambushed Omar's Yuan fleet in the third Battle of Bạch Đằng.[64] The Vietnamese forces placed hidden metal-tipped wooden stakes in the riverbed and attacked the fleet once it had been impaled on the stakes.[69] Omar himself was taken as a prisoner of war.[66][10] The Yuan fleet was destroyed and the army retreated in disarray without supplies.[69] A few days later, Zhang Wenhu who thought that the Yuan armies were still in Vạn Kiếp, unaware of the Yuan defeat, his transport fleet sailed into the Bạch Đằng river and was destroyed by the Vietnamese navy.[10] Only Wenhu and few Yuan soldiers managed to escaped.[10]

Several thousand Yuan troops, unfamiliar with the terrain, were lost and never regained contact with the main force.[64] An account of the battle from , a Vietnamese scholar who defected to the Yuan in 1285, said that the remnants of the army followed him north in retreat and reached Yuan-controlled territory on Lunar New Year's Day in 1289.[64] When the Yuan troops were withdrawn before malaria season, Lê Tắc went north with them.[71] Many of his companions, ten thousand died between the mountain passes of the Sino-Viet borderlands.[64] After the war Lê Tắc got permanently exiled in China, and was appointed by the Yuan government the position of Prefect of Pacified Siam (Tongzhi Anxianzhou).[71]

Aftermath[]

Yuan dynasty[]

The Yuan dynasty was unable to militarily defeat the Vietnamese and the Cham.[72] Kublai was angry over the Yuan defeats in Đại Việt, banished prince Toghon to Yangzhou[73] and wanted to launch another invasion, but was persuaded in 1291 to send the Minister of Rites to induce Trần Nhân Tông to come to China. The Yuan mission arrived in Vietnamese capital on 18 March 1292 and stayed in a guesthouse, where the king made a protocol with Zhang.[74] Trần Nhân Tông sent a mission with a memorial to return with Zhang Lidao to China. In memorial, Trần Nhân Tông explained his inability to visit China. The detail said among ten Vietnamese envoys to Dadu, six or seven of them died on the way.[75] He wrote a letter to Kublai Khan describing the death and destruction the Mongol armies wrought on Dai Viet, vividly recounting the brutality of the soldiers, and the desecration of sacred Buddhist sites.[72] Instead of going to Dadu personally by himself, the Vietnamese king sent a gold statue to Yuan court.[10] Another Yuan mission was sent in September 1292.[75] As late as 1293, Kublai Khan planned a fourth military campaign to install Trần Ích Tắc as the King of Đại Việt, but the plans for the campaign were halted when Kublai Khan died in early 1294.[71] The new Yuan emperor, Temür Khan announced that the war with Đại Việt was over, and he sent a mission to Đại Việt to restore friendly relations between two countries.[76]

Đại Việt[]

Three Mongol and Yuan invasions devastated Đại Việt, but the Vietnamese did not succumb to Yuan demands. Eventually, not a single Trần king or prince visited China.[77] The Trần dynasty of Đại Việt decided to accept the supremacy of the Yuan dynasty in order to avoid further conflicts. In 1289, Đại Việt released most of Mongol prisoners of war to China, but Omar, whose return Kublai particularly demanded, was intentionally drowned when the boat transporting him was contrived to sink.[66] In the winter of 1289–1290, king Trần Nhân Tông led an attack into modern-day Laos, against the advice of his advisors, with the goal of preventing raids from the inhabitants of the highlands.[78] Famines and starvations ravaged the country from 1290 to 1292. There were no records of what caused the crop failures, but possible factors included neglect of the water control system due to the war, the mobilization of men away from the rice fields, and floods or drought.[78] Although Đại Việt repelled the Yuan, the capital Thăng Long was razed, many Buddhist sites were decimated, and the Vietnamese suffered major losses in population and property.[72] Nhân Tông rebuilt the Thăng Long citadel in 1291 and 1293.[72]

In 1293, Kublai detained the Vietnamese envoy, Đào Tử Kí, because Trần Nhân Tông refused to go to Beijing in person. Kublai's successor Temür Khan (r.1294-1307), later released all detained envoys and resumed their tributary relationship initially established after the first invasion, which continued to the end of the Yuan.[16]

Champa[]

The Champa Kingdom decided to accept the supremacy of the Yuan dynasty and also established a tributary relationship with the Yuan.[16] In 1305, Cham king Chế Mân (r. 1288 – 1307) married the Vietnamese princess Huyền Trân (daughter of Trần Nhân Tông) as he ceded two provinces Ô and Lý to Đại Việt.[14]

Transmission of gunpowder[]

Before the 13th century, gunpowder in Vietnam was used in form of firecrackers for entertaining.[79] During the Mongol invasions, a flux of Chinese immigrants from the Southern Song fled to Southeast Asia including Dai Viet and Champa, carried along with gunpowder weapons, such as fire arrows and fire lance techniques, and the Vietnamese and the Cham developed these weapons further in the next century.[80] When the Ming dynasty conquered Đại Việt in 1407, they found that the Vietnamese were skillful in making a type of fire lance which fires out an arrow and a number of lead bullets as co-viative projectiles.[81][82]

Legacy[]

Despite the military defeats suffered during the campaigns, they are often treated as a success by historians for the Mongols due to the establishment of tributary relations with Đại Việt and Champa.[11][12][13] The initial Mongol goal of placing Đại Việt, a tributary state of the Southern Song dynasty, as their own tributary state was accomplished after the first invasion.[11] However, the Mongols failed to impose their demands of greater tribute and direct darughachi oversight over Đại Việt's internal affairs during their second invasion and their goal of replacing the uncooperative Trần Nhân Tông with Trần Ích Tắc as the King of Đại Việt during the third invasion.[35][64] Nonetheless, friendly relations were established and Dai Viet continued to pay tribute to the Mongol court.[83][84]

Vietnamese historiography emphasizes the Vietnamese military victories.[11] The three invasions, and the Battle of Bạch Đằng in particular, are remembered within Vietnam and Vietnamese historiography as prototypical examples of Vietnamese resistance against foreign aggression.[35] Prince Trần Quốc Tuấn is remembered as the national hero who saved Vietnamese independence.[73]

Notes[]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Anderson 2014, p. 129.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Atwood 2004, p. 579.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hà & Phạm 2003, p. 66-68.

- ^ Man 2012, p. 350.

- ^ Atwood 2004, p. 579–580.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Anderson 2014, p. 127.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Lo 2012, p. 288.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Lo 2012, p. 292.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Man 2012, p. 351.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Lo 2012, p. 302.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Baldanza 2016, p. 17.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Weatherford 2005, p. 212.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hucker 1975, p. 285.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Aymonier 1893, p. 16.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Haw 2013, p. 361-371.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bulliet et al. 2014, p. 336.

- ^ Baldanza 2016, p. 17-26.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Allsen 2006, p. 405.

- ^ Rossabi 2009, p. 27.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Anderson 2014, p. 116.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Herman 2020, p. 47.

- ^ Anderson 2014, p. 117.

- ^ Allsen 2006, p. 405-406.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Anderson 2014, p. 118.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Allsen 2006, p. 407.

- ^ Sun 2014, p. 206.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Sun 2014, p. 207.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Baldanza 2016, p. 18.

- ^ Vu & Sharrock 2014, p. 84.

- ^ Anderson 2014, p. 121.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Vu & Sharrock 2014, p. 85.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lo 2012, p. 284.

- ^ Buell, P.D. "Mongols in Vietnam: end of one era, beginning of another". First Congress of the Asian Association of World Historians 29–31 May 2009 Osaka University Nakanoshima-Center.

- ^ Vu & Sharrock 2014, p. 86.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Baldanza 2016, p. 19.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lo 2012, p. 285.

- ^ Grousset 1970, p. 290.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lo 2012, p. 286.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Lo 2012, p. 287.

- ^ Delgado 2008, p. 158.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Purton 2010, p. 201.

- ^ Lo 2012, p. 288-289.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Lo 2012, p. 289.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Delgado 2008, p. 159.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Anderson 2014, p. 122.

- ^ Sun 2014, p. 208.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Haw 2006, p. 105.

- ^ Sun 2014, p. 212.

- ^ Sun 2014, p. 213.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Anderson 2014, p. 123.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Taylor 2013, p. 133.

- ^ Lo 2012, p. 291.

- ^ Anderson 2014, p. 124.

- ^ Harris 2008, p. 354.

- ^ Haw 2006, p. 107.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Lo 2012, p. 293.

- ^ Anderson 2014, p. 125.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Anderson 2014, p. 126.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lo 2012, p. 294.

- ^ Taylor 2013, p. 134.

- ^ Stone 2017, p. 76.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lo 2012, p. 295.

- ^ Taylor 2013, p. 135.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j Baldanza 2016, p. 24.

- ^ Lo 2012, p. 296.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Taylor 2013, p. 136.

- ^ Lo 2012, p. 281.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lo 2012, p. 297.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Baldanza 2016, p. 26.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Lo 2012, p. 301.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Baldanza 2016, p. 25.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Miksic & Yian 2016, p. 489.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Man 2012, p. 353.

- ^ Sun 2014, p. 221.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sun 2014, p. 223.

- ^ Lo 2012, p. 303.

- ^ Sun 2014, p. 227.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Taylor 2013, p. 137.

- ^ Baldanza 2016, p. 42.

- ^ Needham 1987, p. 313.

- ^ Needham 1987, p. 240.

- ^ Needham 1987, p. 311.

- ^ Simons 1998, p. 53.

- ^ Walker 2012, p. 242.

Sources[]

- Allsen, Thomas (2006), "The rise of the Mongolian empire and Mongolian rule in north China", in Franke, Herbert; Twittchet, Denis C. (eds.), The Cambridge History of China - Volume 6: Alien regimes and border states, 907—1368, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 321–413

- Anderson, James A. (2014), "Man and Mongols: the Dali and Đại Việt Kingdoms in the Face of the Northern Invasions", in Anderson, James A.; Whitmore, John K. (eds.), China's Encounters on the South and Southwest: Reforging the Fiery Frontier Over Two Millennia, United States: Brills, pp. 106–134, ISBN 978-9-004-28248-3

- Atwood, Christopher Pratt (2004). Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. New York: Facts of File. ISBN 978-0-8160-4671-3.

- Aymonier, Etienne (1893). The History of Tchampa (the Cyamba of Marco Polo, Now Annam Or Cochin-China). Oriental University Institute.

- Baldanza, Kathlene (2016). Ming China and Vietnam: Negotiating Borders in Early Modern Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-53131-0.

- Bulliet, Richard; Crossley, Pamela; Headrick, Daniel; Hirsch, Steven; Johnson, Lyman (2014). The Earth and Its Peoples: A Global History. Cengage Learning. ISBN 9781285965703.

- Chapuis, Oscar (1995). A history of Vietnam: from Hong Bang to Tu Duc. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-29622-7.

- Connolly, Peter; Gillingham, John; Lazenby, John, eds. (1998). The Hutchinson Dictionary of Ancient & Medieval Warfare. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-57958-116-9.

- Delgado, James P. (2008). Khubilai Khan's Lost Fleet: In Search of a Legendary Armada. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 978-0-520-25976-8.

- Dutton, George; Werner, Jayne; Whitmore, John K., eds. (2012). Sources of Vietnamese Tradition. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-51110-0.

- Grousset, René (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1.

- Hà, Văn Tấn; Phạm, Thị Tâm (2003). "III: Cuộc kháng chiến lần thứ nhất" [III: The First Resistance War]. Cuộc kháng chiến chống xâm lược Nguyên Mông thế kỉ XIII [The resistance against the Mongol invasion in the 13th century] (in Vietnamese). People's Army Publishing House. ISBN 978-604-89-3615-0.

- Hall, Kenneth R. (2008). Secondary Cities and Urban Networking in the Indian Ocean Realm, C. 1400-1800. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-2835-0.

- Haw, Stephen G. (2013). "The deaths of two Khaghans: a comparison of events in 1242 and 1260". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 76 (3): 361–371. doi:10.1017/S0041977X13000475. JSTOR 24692275.

- Haw, Stephen G. (2006), Marco Polo's China: A Venetian in the Realm of Khubilai Khan, Taylor & Francis

- Herman, John E. (2020), Amid the Clouds and Mist China's Colonization of Guizhou, 1200–1700, Harvard University Asia Center, ISBN 978-0-674-02591-2

- Hucker, Charles O. (1975). China's Imperial Past: An Introduction to Chinese History and Culture. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804723534.

- Lo, Jung-pang (2012). Elleman, Bruce A. (ed.). China as a Sea Power, 1127-1368: A Preliminary Survey of the Maritime Expansion and Naval Exploits of the Chinese People During the Southern Song and Yuan Periods. Singapore: NUS Press. ISBN 9789971695057.

- Man, John (2012). Kublai Khan. Transworld.

- Miksic, John Norman; Yian, Go Geok (2016). Ancient Southeast Asia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-27903-7.

- Needham, Joseph (1987), Science & Civilisation in China, V:5 pt. 7: The Gunpowder Epic, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-30358-3

- Purton, Peter (2010), A History of the Late Medieval Siege 1200-1500, The Boydell Press

- Rossabi, Morris (2009). Khubilai Khan: His Life and Times. University of California Press .

- Simons, G. (1998). The Vietnam Syndrome: Impact on US Foreign Policy. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Stone, Zofia (2017). Genghis Khan: A Biography. Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. ISBN 978-93-86367-11-2.

- Sun, Laichen (2014), "Imperial Ideal Compromised: Northern and Southern Courts Across the New Frontier in the Early Yuan Era", in Anderson, James A.; Whitmore, John K. (eds.), China's Encounters on the South and Southwest: Reforging the Fiery Frontier Over Two Millennia, United States: Brills, pp. 193–231

- Taylor, Keith W. (2013). A History of the Vietnamese. Cambridge University Press.

- Vu, Hong Lien; Sharrock, Peter (2014). Descending Dragon, Rising Tiger: A History of Vietnam. Reaktion Books.

- Walker, Hugh Dyson (2012). East Asia: A New History. ISBN 978-1477265161.

- Weatherford, Jack (2005). Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-609-80964-8.

Primary sources[]

- Harris, Peter (2008), The Travels of Marco Polo, the Venetian, Alfred A. Knopf

- Lê, Tắc (1961), An Nam chí lược, A brief history of Annam, University of Hue

- Rustichello da Pisa, The Travels of Marco Polo

- Song Lian (宋濂), History of Yuan (元史)

- Rashid-al-Din Hamadani, Jami' al-tawarikh

See also[]

| Library resources about Mongol invasions of Vietnam |

- Kingdom of Champa

- Battle of Bạch Đằng (1288)

- Tran Hung Dao

- Yuan dynasty

- Kublai Khan

- Mongol invasions

- Trần dynasty military tactics and organization

- Mongol military tactics and organization

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/.

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/.

- Invasions by the Mongol Empire

- Wars involving Champa

- Wars involving the Đại Việt Kingdom

- Wars involving Imperial China

- Wars involving the Yuan dynasty

- 1250s conflicts

- 1280s conflicts

- 1280s in Asia

- History of Champa

- History of Đại Việt

- 1257 in the Mongol Empire

- 1258 in the Mongol Empire

- 1284 in the Mongol Empire

- 1285 in the Mongol Empire

- 1287 in the Mongol Empire

- 1288 in the Mongol Empire

- Invasions of Vietnam

- Kublai Khan

- 13th century in Vietnam

- Wars between China and Vietnam

- History of Vietnam