Munda languages

| Munda | |

|---|---|

| Mundaic | |

| Geographic distribution | India, Bangladesh |

| Linguistic classification | Austroasiatic

|

| Proto-language | Proto-Munda |

| Subdivisions | |

| ISO 639-2 / 5 | mun |

| Glottolog | mund1335 |

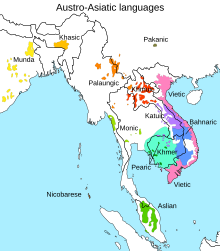

Map of areas with significant concentration of Munda speakers | |

The Munda languages are a language family spoken by about nine million people in India and Bangladesh.[1][2] Historically, they have been called the Kolarian languages. They constitute a branch of the Austroasiatic language family, which means they are related to languages such as Mon and Khmer languages and Vietnamese, as well as minority languages in Thailand and Laos and the minority Mangic languages of South China.[3] The origins of the Munda languages are not known, but they predate the other languages of eastern India.[citation needed] Ho, Mundari, and Santali are notable languages of this group.[4][5][1]

The family is generally divided into two branches: North Munda, spoken in the Chota Nagpur Plateau of Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, West Bengal, and Odisha, and South Munda, spoken in central Odisha and along the border between Andhra Pradesh and Odisha.[6][7][1]

North Munda, of which Santali is the most widely spoken, has twice as many speakers as South Munda. After Santali, the Mundari and Ho languages rank next in number of speakers, followed by Korku and Sora. The remaining Munda languages are spoken by small, isolated groups of people and are poorly known.[1]

Characteristics of the Munda languages include three grammatical numbers (singular, dual and plural), two genders (animate and inanimate), a distinction between inclusive and exclusive first person plural pronouns, the use of suffixes or auxiliaries to indicate tense,[8] and partial, total, and complex reduplication, as well as switch-reference.[9][8] The Munda languages are also polysynthetic and agglutinating.[10][11]

In Munda sound systems, consonant sequences are infrequent except in the middle of a word. Other than in Korku, whose syllables show a distinction between high and low tone, accent is predictable in the Munda languages.

Origin[]

Most linguists, like Paul Sidwell (2018), suggest that the proto-Munda language probably split from proto-Austroasiatic somewhere in Indochina and arrived on the coast of modern-day Odisha about 4000–3500 years ago and spread after the Indo-Aryan migration to the region.[12]

Rau and Sidwell (2019),[13][14] along with Blench (2019),[15] suggest that pre-Proto-Munda had arrived in the Mahanadi River Delta around 1,500 BCE from Southeast Asia via a maritime route, rather than overland. The Munda languages then subsequently spread up the Mahanadi watershed.

Classification[]

Munda consists of five uncontroversial branches. However, their interrelationship is debated.

Diffloth (1974)[]

The bipartite Diffloth (1974) classification is widely cited:

- North Munda

- South Munda

Diffloth (2005)[]

Diffloth (2005) retains Koraput (rejected by Anderson, below) but abandons South Munda and places Kharia–Juang with the northern languages:

| Munda |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Anderson (1999)[]

Gregory Anderson's 1999 proposal is as follows.[16]

- North Munda

- South Munda (3 branches)

However, in 2001, Anderson split Juang and Kharia apart from the Juang-Kharia branch and also excluded Gtaʔ from his former Gutob–Remo–Gtaʔ branch. Thus, his 2001 proposal includes 5 branches for South Munda.

Anderson (2001)[]

Anderson (2001) follows Diffloth (1974) apart from rejecting the validity of Koraput. He proposes instead, on the basis of morphological comparisons, that Proto-South Munda split directly into Diffloth's three daughter groups, Kharia–Juang, Sora–Gorum (Savara), and Gutob–Remo–Gtaʼ (Remo).[18]

His South Munda branch contains the following five branches, while the North Munda branch is the same as those of Diffloth (1974) and Anderson (1999).

- Note: "↔" = shares certain innovative isoglosses (structural, lexical). In Austronesian and Papuan linguistics, this has been called a "linkage" by Malcolm Ross.

Sidwell (2015)[]

Paul Sidwell (2015:197)[19] considers Munda to consist of 6 coordinate branches, and does not accept South Munda as a unified subgroup.

Distribution[]

| Language name | Number of speakers (2011) | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Korwa | 28,400 | Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand |

| Birjia | 25,000 | Jharkhand, West Bengal |

| Mundari (inc. Bhumij) | 1,600,000 | Jharkhand, Odisha, Bihar |

| Asur | 7,000 | Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Odisha |

| Ho | 1,400,000 | Jharkhand, Odisha, West Bengal |

| Birhor | 2,000 | Jharkhand |

| Santali | 7,400,000 | Jharkhand, West Bengal, Odisha, Bihar |

| Turi | 2,000 | Jharkhand |

| Korku | 727,000 | Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra |

| Kharia | 298,000 | Odisha, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh |

| Juang | 30,400 | Odisha |

| Gtaʼ | 4,500 | Odisha |

| Bonda | 9,000 | Odisha |

| Gutob | 10,000 | Odisha, Andhra Pradesh |

| Gorum | 20 | Odisha, Andhra Pradesh |

| Sora | 410,000 | Odisha, Andhra Pradesh |

| Juray | 25,000 | Odisha |

| Lodhi | 25,000 | Odisha, West Bengal |

| Koda | 47,300 | West Bengal, Odisha, Bangladesh |

Reconstruction[]

The proto-forms have been reconstructed by Sidwell & Rau (2015: 319, 340-363).[20] Proto-Munda reconstruction has since been revised and improved by Rau (2019).[21][22]

See also[]

References[]

Notes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Anderson, Gregory D. S. (29 March 2017), "Munda Languages", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199384655.013.37, ISBN 978-0-19-938465-5

- ^ Hock, Hans Henrich; Bashir, Elena, eds. (23 January 2016). The Languages and Linguistics of South Asia. doi:10.1515/9783110423303. ISBN 9783110423303.

- ^ Bradley (2012) notes, MK in the wider sense including the Munda languages of eastern South Asia is also known as Austroasiatic

- ^ Pinnow, Heinz-Jurgen. "A comparative study of the verb in Munda language" (PDF). Sealang.com. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ Daladier, Anne. "Kinship and Spirit Terms Renewed as Classifiers of "Animate" Nouns and Their Reduced Combining Forms in Austroasiatic". Elanguage. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ Bhattacharya, S. (1975). "Munda studies: A new classification of Munda". Indo-Iranian Journal. 17 (1): 97–101. doi:10.1163/000000075794742852. ISSN 1572-8536.

- ^ "Munda languages". The Language Gulper. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Gregory D. S. Anderson The Munda Verb: Typological Perspectives", Annual Review of South Asian Languages and Linguistics, Trends in Linguistics. Studies and Monographs [TiLSM], Berlin, New York: Mouton de Gruyter, 2008, doi:10.1515/9783110211504.4.265, ISBN 978-3-11-021150-4

- ^ Anderson, Gregory D. S. (7 May 2018), Urdze, Aina (ed.), "Reduplication in the Munda languages", Non-Prototypical Reduplication, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 35–70, doi:10.1515/9783110599329-002, ISBN 978-3-11-059932-9

- ^ Donegan, Patricia Jane; Stampe, David. "South-East Asian Features in the Munda Languages". Berkley Linguistics Society.

- ^ Anderson, Gregory D. S. (1 January 2014), "5 Overview of the Munda Languages", The Handbook of Austroasiatic Languages (2 vols), BRILL, pp. 364–414, doi:10.1163/9789004283572_006, ISBN 978-90-04-28357-2

- ^ Sidwell, Paul. 2018. Austroasiatic Studies: state of the art in 2018. Presentation at the Graduate Institute of Linguistics, National Tsing Hua University, Taiwan, 22 May 2018.

- ^ Rau, Felix; Sidwell, Paul (2019). "The Munda Maritime Hypothesis". Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society (JSEALS). 12 (2). hdl:10524/52454. ISSN 1836-6821.

- ^ Rau, Felix and Paul Sidwell 2019. "The Maritime Munda Hypothesis." ICAAL 8, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 29–31 August 2019. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3365316

- ^ Blench, Roger. 2019. The Munda maritime dispersal: when, where and what is the evidence?

- ^ Anderson, Gregory D.S. (1999). "A new classification of the Munda languages: Evidence from comparative verb morphology." Paper presented at 209th meeting of the American Oriental Society, Baltimore, MD.

- ^ Anderson, G.D.S. (2008). ""Gtaʔ" The Munda Languages. Routledge Language Family Series. London: Routledge. pp. 682-763". Routledge Language Family Series (3): 682–763.

- ^ Anderson, Gregory D S (2001). A New Classification of South Munda: Evidence from Comparative Verb Morphology. Indian Linguistics. 62. Poona: Linguistic Society of India. pp. 21–36.

- ^ Sidwell, Paul. 2015. "Austroasiatic classification." In Jenny, Mathias and Paul Sidwell, eds (2015). The Handbook of Austroasiatic Languages. Leiden: Brill.

- ^ Sidwell, Paul and Felix Rau (2015). "Austroasiatic Comparative-Historical Reconstruction: An Overview." In Jenny, Mathias and Paul Sidwell, eds (2015). The Handbook of Austroasiatic Languages. Leiden: Brill.

- ^ Rau, Felix. (2019). Advances in Munda historical phonology. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3380908

- ^ Rau, Felix. (2019). Munda cognate set with proto-Munda reconstructions (Version 0.1.0) [Data set]. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3380874

General references[]

- Diffloth, Gérard. 1974. "Austro-Asiatic Languages". Encyclopædia Britannica. pp 480–484.

- Diffloth, Gérard. 2005. "The contribution of linguistic palaeontology to the homeland of Austro-Asiatic". In: Sagart, Laurent, Roger Blench and Alicia Sanchez-Mazas (eds.). The Peopling of East Asia: Putting Together Archaeology, Linguistics and Genetics. RoutledgeCurzon. pp 79–82.

Further reading[]

- Gregory D S Anderson, ed. (2008). Munda Languages. Routledge Language Family Series. 3. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-32890-6.

- Anderson, Gregory D S (2007). The Munda verb: typological perspectives. Trends in linguistics. 174. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-018965-0.

- Anderson, Gregory D. S. (2015). "Prosody, phonological domains and the structure of roots, stems and words in the Munda languages in a comparative/historical light". Journal of South Asian Languages and Linguistics 2. 2: 163–183.

- Donegan, Patricia; David Stampe (2002). South-East Asian Features in the Munda Languages: Evidence for the Analytic-to-Synthetic Drift of Munda. In Patrick Chew, ed., Proceedings of the 28th Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, Special Session on Tibeto-Burman and Southeast Asian Linguistics, in honour of Prof. James A. Matisoff. 111-129. Berkeley, CA: Berkeley Linguistics Society.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Śarmā, Devīdatta (2003). Munda: sub-stratum of Tibeto-Himalayan languages. Studies in Tibeto-Himalayan languages. 7. New Delhi: Mittal Publications. ISBN 81-7099-860-3.

- Newberry, J (2000). North Munda hieroglyphics. Victoria BC CA: J Newberry.

- Varma, Siddheshwar (1978). Munda and Dravidian languages: a linguistic analysis. Hoshiarpur: Vishveshvaranand Vishva Bandhu Institute of Sanskrit and Indological Studies, Panjab University. OCLC 25852225.

- 2006-a. Munda Languages. In E. K. Brown (ed.) Encyclopedia of Languages and Linguistics. Oxford: Elsevier Press.

- Zide, Norman H. and G. D. S. Anderson. 1999. The Proto-Munda Verb and Some Connections with Mon-Khmer. In P. Bhaskararao (ed.) Working Papers International Symposium on South Asian Languages Contact and Convergence, and Typology. Tokyo. pp. 401–21.

- Zide, Norman H. and Gregory D. S. Anderson. 2001. The Proto-Munda Verb: Some Connections with Mon-Khmer. In K. V. Subbarao and P. Bhaskararao (eds.) Yearbook of South-Asian Languages and Linguistics-2001. Delhi: Sage Publications. pp. 517–40.

- Gregory D. S. Anderson and John P. Boyle. 2002. Switch-Reference in South Munda. In Marlys A. Macken (ed.) Papers from the 10th Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society. Tempe, AZ: Arizona State University, South East Asian Studies Program, Monograph Series Press. pp. 39–54.

- Gregory D. S. Anderson and Norman H. Zide. 2001. Recent Advances in the Reconstruction of the Proto-Munda Verb. In L. Brinton (ed.) Historical Linguistics 1999. Amsterdam: Benjamins. pp. 13–30.

- Historical migrations

- Blench, Roger. 2019. The Munda maritime dispersal: when, where and what is the evidence?

- Rau, Felix and Paul Sidwell 2019. "The Maritime Munda Hypothesis." ICAAL 8, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 29–31 August 2019. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3365316

- Rau, Felix and Paul Sidwell 2019. "The Maritime Munda Hypothesis." Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society 12.2 (2019): 31-53

External links[]

- SEAlang Munda Languages Project

- Munda Dictionaries Project (Kiel, Peterson)

- Donegan & Stampe Munda site

- Munda languages at Living Tongues

- bibliography

- The Ho language webpage by K. David Harrison, Swarthmore College

- RWAAI (Repository and Workspace for Austroasiatic Intangible Heritage)

- http://hdl.handle.net/10050/00-0000-0000-0003-66EE-3@view Munda languages in RWAAI Digital Archive

- Munda languages