National identity card (France)

| French national identity card Carte nationale d’identité | |

|---|---|

Front of the card | |

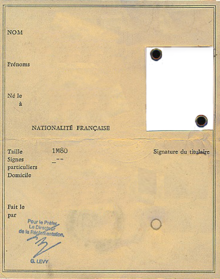

Back of the card | |

| Type | Identity card, optional replacement for passport in the listed countries |

| Issued by | |

| Valid in | |

The French national identity card (French: carte nationale d’identité or CNI) is an official identity document consisting of an electronic ID-1 card bearing a photograph, name and address. While the identity card is non-compulsory, all persons must possess some form of valid government-issued identity documentation.[1]

Identity cards, valid for a period of 10 years, are issued by the local préfecture, sous-préfecture, mairie (in France) or in French consulates (abroad) free of charge. A fingerprint of the holder is taken, which is stored in paper files and which can only be accessed by a judge in closely defined circumstances. A central database duplicates the information on the card, but strict laws limit access to the information and prevent it being linked to other databases or records.

The cards may be used to verify identity and nationality and may also be used as a travel document within Europe (except Belarus, Russia and Ukraine) as well as French overseas territories, Anguilla, Egypt, Turkey, Georgia, Dominica (max 14 days), Montserrat, Saint Lucia and on organized tours to Tunisia[2] instead of a French passport. The cards are widely used for other purposes — for example, when opening a bank account, or when making a payment by cheque.

History[]

While passports have been issued in France, under one form or another, since the Middle Ages, the identity card is a 20th-century innovation. The first ID was issued to foreigners in residence in France in 1917, in order to control the foreign population in a time of war and spy scare. The first card for Frenchmen was created by the Police Prefect of the Seine département, then the Paris local authority, in 1921. This carte d'identité des Français was a non-compulsory ID document and was only issued in the Paris region.

Following defeat in the Battle of France, the Vichy government created a new national identity card under the law of October 27, 1940. This new ID was compulsory for every French person over the age of 16. A central record was also instituted. From 1942, French Jews had the word "Jew" added to their card in red, which helped the Vichy authorities identify 76,000 for deportation as part of the Holocaust.

Under the decree 55-1397 of October 22, 1955[3] a revised non-compulsory card, the carte nationale d'identité (CNI) was introduced, and the central records abandoned. With the introduction of lamination in 1988 it was renamed the carte nationale d’identité sécurisée (CNIS) (secure national identity card). In 1995 the cards were made machine-readable. It became free in 1998.

On 15 March 2021 a new electronic model has been released.[4]

Use[]

Identification document[]

The French national identity card can be used as an identification document in France in situations such as opening a bank account, identifying oneself to government agencies, proving one's identity and regular immigration status to a law enforcement official etc.

Similarly, French citizens exercising their right to free movement in another EU/EEA member state or Switzerland are entitled to use their French national identity card as an identification document when dealing not just with government authorities, but also with private sector service providers. For example, if a supermarket in Ireland refuses to accept a French national identity card as proof of age when a French citizen attempts to purchase an age-restricted product, and insists on the production of an Irish passport, driving license or other identity document, the supermarket would, in effect, be discriminating against this individual on this basis of his/her nationality in the provision of a service, thereby contravening the prohibition in Art 20(2) of Directive 2006/123/EC of discriminatory treatment relating to the nationality of a service recipient in the conditions of access to a service which are made available to the public at large by a service provider.[5]

In practice, the ID card can often be used for various identification purposes worldwide, such as for age verification in bars or checking in at hotels.

Travel document[]

The French national identity card can be used as a travel document (instead of a French passport) to/from the following countries:

All countries in Europe except Belarus, Russia and Ukraine

All countries in Europe except Belarus, Russia and Ukraine French overseas territories

French overseas territories Anguilla (max 24 hours, 72 hours for St Martin residents) [6]

Anguilla (max 24 hours, 72 hours for St Martin residents) [6] Dominica (max 14 days)[7]

Dominica (max 14 days)[7] Egypt (a passport photo must be supplied to the border authorities upon entry)[8]

Egypt (a passport photo must be supplied to the border authorities upon entry)[8] Montserrat

Montserrat Saint Lucia[9]

Saint Lucia[9] Tunisia (only when on a package tour)

Tunisia (only when on a package tour) Turkey[10]

Turkey[10]

Previously, the ![]() Dominican Republic,

Dominican Republic, ![]() Mauritius,

Mauritius, ![]() Morocco,

Morocco, ![]() Saint Vincent and the Grenadines,

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, ![]() Senegal and

Senegal and ![]() Sint Maarten permitted French citizens to travel to their countries on the strength of a French national identity card alone. However, the six countries' authorities have since required French citizens to use their passports when entering/leaving.[11]

Sint Maarten permitted French citizens to travel to their countries on the strength of a French national identity card alone. However, the six countries' authorities have since required French citizens to use their passports when entering/leaving.[11]

Prior to 1 January 2013, unaccompanied minors under the age of 18 who travelled outside metropolitan France using their French national identity cards were required to obtain an autorisation de sortie du territoire (AST).[12] In order to obtain an AST, one of the minor's parents had to visit the local mayor's office. On 1 January 2013, the obligation to obtain an AST was removed, and all minors are now able solely to use their French national identity cards when leaving/re-entering France without a parent.[13] However, whilst the French border authorities no longer require an AST from the parent(s) of an unaccompanied minor when he/she leaves or re-enters France, the border authorities of other countries may require the minor to present some form of written approval from the his/her parent(s) before admitting him/her.

Validity[]

Prior to 1 January 2014, French national identity cards were issued with a maximum period of validity of 10 years.

On 1 January 2014, the period of validity of new cards issued to adults was increased from 10 to 15 years.

In addition, on the same day, a retroactive change in the period of validity came into effect by virtue of Decree 2013-1188.[14] As a result, all French national identity cards issued between 2 January 2004 and 31 December 2013 to adults had their period of validity automatically extended from 10 years to 15 years.[15] This extension took place without the need for any physical amendment to the expiry date which appears on eligible cards — for example, the holder of a French national identity card issued on 1 February 2004 (when he/she was already an adult) will actually be valid until 1 February 2019 automatically without the need for any amendment to the card (even though it states on the card that it will expire on 1 February 2014).

As of 15 March 2021, the new id card lasts 10 years.[4]

Design[]

The card measures 105 x 74 mm. The paper card was laminated and has rounded corners until a new credit card sized plastic format was introduced as part of an overhaul in 2021. All the information on the card was given in the French language only until English was added with the new card design.

Whilst French passports and residence permits (issued to non-EU/EEA/Swiss citizens residing in France) contain an RFID chip, the design of the French national identity card remained unchanged from 1994 to 2021 and so cards were issued without an RFID chip (unlike a number of other EU member states which have updated the design of their national identity cards to include an RFID chip) until 2021. Whilst fingerprints are collected as part of the application process for the card, fingerprint images were neither printed on the card nor stored in an RFID chip embedded within the card.

Front side[]

The front side of the previous design (used from 1994 to 2021) featured the words "RÉPUBLIQUE FRANÇAISE" across the top and "Carte national d'identité/ National Identity Card" as well on cards issues since 2021 on the front, plus the following information:

- Card number

- Nationality (French)

- Photograph of the holder

- Surname

- Given name(s)

- Sex

- Date of birth (dd.mm.yyyy)

- Place of birth (If born in France, only the name and number of the département)

- Height (in metres, on the back of the new cards)

- Signature of holder

At the bottom of the front side (the back on the new design) is a two-line machine readable zone.

Machine-readable zone[]

The format of the first row is:

| positions | length | chars | meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | alpha | I |

| 2 | 1 | alpha | Type, at discretion of states (D in that case) |

| 3–5 | 3 | alpha | FRA // issuing country (ISO 3166-1 alpha-3 code with modifications) |

| 6–30 | 25 | alpha | Card holder's last name followed by '<' symbols to fill any unused space |

| 31-33 | 3 | alpha+num | Digits 5-7 of ID card number, department of issuance. |

| 34-36 | 3 | num | Office of issuance |

| 31-36 | 6 | alpha | On some cards 31-36 will instead be filled with <<<<< |

The format of the second row is:

| positions | length | chars | meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-4 | 4 | num | Digits 1-2 are year of issuance, 3-4 are month of issuance |

| 5-7 | 3 | alpha+num | Department of issuance. Same as characters 31-33 on the first line. |

| 8–12 | 5 | num | Assigned by the Management Center in chronological order in relation to the place of issue and the date of application. |

| 13 | 1 | num | Check digit over digits 1–12 |

| 14–27 | 14 | alpha | First name followed by given names separated by two filler characters |

| 28-33 | 6 | num | Birth date (YYMMDD) |

| 34 | 1 | num | Check digit over digits 28-33 |

| 35 | 1 | alpha | Gender (M or F) |

| 36 | 1 | num | Check digit over digits 1-36 in first row combined with digits 1-35 in second row |

Rear side[]

The rear side contains the following information:

- Residential address of the holder

- Date of expiry (dd.mm.yyyy, on the front of new cards)

- Date of issue (dd.mm.yy)

- Issuing authority

- Signature of the issuing authority

- Credit card like microchip and datamatrix code on cards issued since 2021

Future changes[]

Following a study launched by French Minister of the Interior Daniel Vaillant in 2001, plans have been proposed to introduce a new identity card, the INES (carte d'identité nationale électronique sécurisée) or 'secure electronic national identity card', to be implemented from around 2007. Similar to a credit card, it is likely that this will contain biometric fingerprint and photograph data on a chip (also recorded on a central database). The scheme has many similarities to the defunct British national identity card and National Identity Register created by the Identity Card Act of 30 March 2006.

The official agency in charge of data use monitoring, the 'national commission for computing and liberties' (commission nationale de l'informatique et des libertés or CNIL) has no official position since the project hasn't been officially submitted yet. CNIL was itself created (in 1978) to guard against the infringement of liberty that might result from the use of information technology, as a result of the public outcry over other plans in the 1970s to issue a 'national identity number' to each citizen, linked to the records of all Government agencies (which would have been similar to the existing numbers in many other European countries: Finland, Sweden, Belgium, Italy, Spain, Estonia, etc.).

Official consultation[]

The largely Government-funded Internet Rights Forum (Forum des droits sur l’Internet) or FDI, was asked by Interior Minister Dominique de Villepin to conduct a public debate on the Internet and throughout the French Regions. The FDI focused on the critics.

The FDI reported to Villepin's successor, Nicolas Sarkozy, on 16 June 2005, stating that 74% were in favour of the cards, 75% in favour of a fingerprint database, and 63% in favour of compulsion. They did, however, make a number of recommendations to change aspects of the proposals.

In response to the Government's debate, a group of French bodies initiated a report and petition against the plans. Founded by the Human Rights League (Ligue des droits de l'Homme), Magistrates' Union (Syndicat de la Magistrature), French Lawyers' Union (Syndicat des Avocats de France), the 'Imagine a United Internet Association' (association Imaginons un Réseau Internet Solidaire), the Group for Rights and Liberties in the face of the Computerisation of Society (intercollectif Droits Et Libertés face à l’Informatisation de la Société) and the French Democratic Lawyers Association (Association française des juristes démocrates), the group submitted an alternative report and petition. This states that:

- The claims that the scheme would reduce fraud were unsubstantiated;

- The argument that the cards would help the fight against terrorism was not appropriate (although ID cards exist in France, they did not prevent the 28/7/1995 terrorist attack);

- There were important risks concerning the protection of a person's private life and their data, especially due to the existence of the proposed central database and its possible uses;

- The introduction of the INES scheme, even if it incorporated the revisions suggested by the FDI, would shatter the social pact between the citizen and the state, and that the proposals should be abandoned.

Over 1000 organisations and individuals backed the report's conclusions. By then end of January 2006 this had risen to over 68 groups and organisations, and over 6,000 individuals.

The Senate named a commission. Its 2005 report pointed the need to fight the existing fraud by a new identity card system which should also protect freedom and privacy.

Legislative progress[]

Although draft legislation was published in 2005, as by the end of 2005 the Government had not set a date for discussion of the proposals in Parliament. As a result, it is unclear if the scheme will go ahead or when it would commence.

A new project, taking into account the criticism and suggestions made in 2005, is under study.

See also[]

- National identity cards in the European Economic Area

- Biometric passport

- Schengen Information System

References[]

- ^ Art. 78-1 to 78-6 of the French Code of criminal procedure (Code de procédure pénale)

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-11-14. Retrieved 2011-01-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Fac-similé JO du 27/10/1955, page 10604 | Legifrance". www.legifrance.gouv.fr. Retrieved 2019-10-23.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "La nouvelle carte nationale d'identité".

- ^ "Answer to a written question - Validity of national ID cards - E-004933/2014". www.europarl.europa.eu. Retrieved 2019-10-23.

- ^ [1]

- ^ étrangères, Ministère de l'Europe et des Affaires. "Dominique- Sécurité". France Diplomatie : : Ministère de l'Europe et des Affaires étrangères (in French). Retrieved 2019-10-23.

- ^ "Egypt Visa on Arrival (Voa) | Obtain a Visa upon Arrival in Egypt".

- ^ étrangères, Ministère de l'Europe et des Affaires. "Sainte-Lucie- Sécurité". France Diplomatie : : Ministère de l'Europe et des Affaires étrangères (in French). Retrieved 2019-10-23.

- ^ "From Rep. of Turkey Ministry of Foreign Affairs". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 2019-10-23.

- ^ "Voyage en République dominicaine : le passeport désormais obligatoire". Voyages & Voyageurs (in French). Retrieved 2019-10-23.

- ^ Circular N°INTD9000124e of 11 May 1990

- ^ "Suppression des autorisations de sortie de territoire à partir du 1er janvier 2013". www.service-public.fr (in French). Retrieved 2019-10-23.

- ^ Décret n° 2013-1188 du 18 décembre 2013 relatif à la durée de validité et aux conditions de délivrance et de renouvellement de la carte nationale d'identité

- ^ l'Intérieur, Ministère de. "Durée de validité de la CNI" (in French). Retrieved 2019-10-23.

External links[]

In English[]

- Council of the European Union: PRADO page on the French national identity card

- French NGOs : no consensus possible on biometric ID-card

In French[]

- Decree 55-1397 of 22 October 1955 relating to the national identity card (Décret n°55-1397 du 22 octobre 1955 relatif à la carte nationale d'identité )

- CNIL - Carte d’identité électronique : la CNIL au cœur d’un débat de société majeur

- Pétition pour le retrait du projet de carte d'identité biométrique

- Le Forum des droits sur l'internet Rappport : Projet de carte nationale d’identité électronique

- Droit-tic Biométrie : une sécurité accrue au détriment des libertés individuelles ?

- Government of France

- National identity cards by country

- Privacy in France