Native American disease and epidemics

| Part of a series on |

| Native Americans |

|---|

It has been suggested that this article be split into articles titled Native American disease and epidemics and Native American health. (Discuss) (October 2020) |

Although a variety of infectious diseases existed in the Americas in pre-Columbian times,[1] the limited size of the populations, smaller number of domesticated animals with zoonotic diseases, and limited interactions between those populations (as compared to areas of Europe and Asia) hampered the transmission of communicable diseases. One notable infectious disease of American origin is syphilis.[1] Aside from that, most of the major infectious diseases known today originated in the Old World (Africa, Asia, and Europe). The American era of limited infectious disease ended with the arrival of Europeans in the Americas and the Columbian exchange of microorganisms, including those that cause human diseases. Eurasian infections and epidemics had major effects on Native American life in the colonial period and nineteenth century, especially.

Europe was a crossroads among many distant, different peoples separated by hundreds, if not thousands, of miles. But repeated warfare by invading populations spread infectious disease throughout the continent, as did trade, including the Silk Road. For more than 1,000 years travelers brought goods and infectious diseases from the East, where some of the latter had jumped from animals to humans. As a result of chronic exposure, many infections became endemic within their societies over time, so that surviving Europeans gradually developed some acquired immunity, although they were still subject to pandemics and epidemics. Europeans carried such endemic diseases when they migrated and explored the New World.

Native Americans often contracted infectious disease through trading and exploration contacts with Europeans, and these were transmitted far from the sources and colonial settlements, through exclusively Native American trading transactions. Warfare and enslavement also contributed to disease transmission. Because their populations had not been previously exposed to most of these infectious diseases, the indigenous people rarely had individual or population acquired immunity and consequently suffered very high mortality. The numerous deaths disrupted Native American societies. This phenomenon is known as the virgin soil effect.[2]

Native Americans are also affected by noncommunicable illnesses related to social changes and contemporary eating habits. Increasing rates of obesity, poor nutrition, sedentary lifestyle, and social isolation affect many Americans. While subject to the same illnesses, Native Americans suffer higher morbidity and mortality to diabetes and cardiovascular disease as well as certain forms of cancer. Social and historical factors tend to promote unhealthy behaviors including suicide and alcohol dependence. Reduced access to health care in Native American communities means that these diseases as well as infections affect more people for longer periods of time.[3]

European contact[]

The arrival and settlement of Europeans in the Americas resulted in what is known as the Columbian exchange. During this period European settlers brought many different technologies, animals, plants, and lifestyles with them, some of which benefited the indigenous peoples. Europeans also took plants and goods back to the Old World. Potatoes and tomatoes from the Americas became integral to European and Asian cuisines, for instance.[4]

But Europeans also unintentionally brought new infectious diseases, including smallpox, bubonic plague, chickenpox, cholera, the common cold, diphtheria, influenza, malaria, measles, scarlet fever, sexually transmitted diseases (with the possible exception of syphilis), typhoid, typhus, tuberculosis (although a form of this infection existed in South America prior to contact),[5] and pertussis.[6][7][8] Each of these resulted in sweeping epidemics among Native Americans, who suffered disability, illness, and a high mortality rate.[8] The Europeans infected with such diseases typically carried them in a dormant state, were actively infected but asymptomatic, or had only mild symptoms, because Europe had been subject for centuries to a selective process by these diseases. The explorers and colonists often unknowingly passed the diseases to natives.[4] The introduction of African slaves and the use of commercial trade routes contributed to the spread of disease.[9][10]

Zoonotic disease are infectious diseases that spread from animals to humans. Journalist Avery Yale Kamila reported: "Because the Wabanaki and other Native Americans did not keep livestock at the time, they weren’t afflicted with zoonotic diseases, such as small pox, measles and tuberculosis, until the 1500s, when Europeans arrived. The Native Americans had no immunity from such diseases and died in droves."

The infections brought by Europeans are not easily tracked, since there were numerous outbreaks and all were not equally recorded. Historical accounts of epidemics are often vague or contradictory in describing how victims were affected. A rash accompanied by a fever might be smallpox, measles, scarlet fever, or varicella, and many epidemics overlapped with multiple infections striking the same population at once, therefore it is often impossible to know the exact causes of mortality (although ancient DNA studies can often determine the presence of certain microbes).[11] Smallpox was the disease brought by Europeans that was most destructive to the Native Americans, both in terms of morbidity and mortality. The first well-documented smallpox epidemic in the Americas began in Hispaniola in late 1518 and soon spread to Mexico.[4] Estimates of mortality range from one-quarter to one-half of the population of central Mexico.[12]

Native Americans initially believed that illness primarily resulted from being out of balance, in relation to their religious beliefs. Typically, Native Americans held that disease was caused by either a lack of magical protection, the intrusion of an object into the body by means of sorcery, or the absence of the free soul from the body. Disease was understood to enter the body as a natural occurrence if a person was not protected by spirits, or less commonly as a result of malign human or supernatural intervention.[13] For example, Cherokee spiritual beliefs attribute disease to revenge imposed by animals for killing them.[14] In some cases, disease was seen as a punishment for disregarding tribal traditions or disobeying tribal rituals.[15] Spiritual powers were called on to cure diseases through the practice of shamanism.[16] Most Native American tribes also used a wide variety of medicinal plants and other substances in the treatment of disease.[17]

Smallpox[]

Smallpox was lethal to many Native Americans, resulting in sweeping epidemics and repeatedly affecting the same tribes. After its introduction to Mexico in 1519, the disease spread across South America, devastating indigenous populations in what are now Colombia, Peru and Chile during the sixteenth century. The disease was slow to spread northward due to the sparse population of the northern Mexico desert region. It was introduced to eastern North America separately by colonists arriving in 1633 to Plymouth, Massachusetts, and local Native American communities were soon struck by the virus. It reached the Mohawk nation in 1634,[18] the Lake Ontario area in 1636, and the lands of other Iroquois tribes by 1679.[19] Between 1613 and 1690 the Iroquois tribes living in Quebec suffered twenty-four epidemics, almost all of them caused by smallpox.[20] By 1698 the virus had crossed the Mississippi, causing an epidemic that nearly obliterated the Quapaw Indians of Arkansas.[15]

The disease was often spread during war. John McCullough, a Delaware captive since July 1756, who was then 15 years old, wrote that the Lenape people, under the leadership of Shamokin Daniel, "committed several depredations along the Juniata; it happened to be at a time when the smallpox was in the settlement where they were murdering, the consequence was, a number of them got infected, and some died before they got home, others shortly after; those who took it after their return, were immediately moved out of the town, and put under the care of one who had the disease before."[21][22][23][24]

By the mid-eighteenth century the disease was affecting populations severely enough to interrupt trade and negotiations. Thomas Hutchins, in his August 1762 journal entry while at Ohio's Fort Miami, named for the Mineamie people, wrote:

The 20th, The above Indians met, and the Ouiatanon Chief spoke in behalf of his and the Kickaupoo Nations as follows: "Brother, We are very thankful to Sir William Johnson for sending you to enquire into the State of the Indians. We assure you we are Rendered very miserable at Present on Account of a Severe Sickness that has seiz'd almost all our People, many of which have died lately, and many more likely to Die..." The 30th, Set out for the Lower Shawneese Town and arriv'd 8th of September in the afternoon. I could not have a meeting with the Shawneese the 12th, as their People were Sick and Dying every day.[25]

On June 24, 1763, during the siege of Fort Pitt, as recorded in his journal by fur trader and militia captain William Trent, dignitaries from the Delaware tribe met with Fort Pitt officials, warned them of "great numbers of Indians" coming to attack the fort, and pleaded with them to leave the fort while there was still time. The commander of the fort refused to abandon the fort. Instead, the British gave as gifts two blankets, one silk handkerchief and one linen from the smallpox hospital, to the two Delaware emissaries Turtleheart and Mamaltee, allegedly in the hope of spreading the deadly disease to nearby tribes, as attested in Trent's journal.[26][27] [28][29][30] The dignitaries were met again later and they seemingly hadn't contracted smallpox.[31] A relatively small outbreak of smallpox had begun spreading earlier that spring, with a hundred dying from it among Native American tribes in the Ohio Valley and Great Lakes area through 1763 and 1764.[31] The effectiveness of the biological warfare itself remains unknown, and the method used is inefficient compared to airborne transmission.[32][33]

21st-century scientists such as V. Barras and G. Greub have examined such reports. They say that smallpox is spread by respiratory droplets in personal interaction, not by contact with fomites, such objects as were described by Trent. The results of such attempts to spread the disease through objects are difficult to differentiate from naturally occurring epidemics.[34][35]

Gershom Hicks, held captive by the Ohio Country Shawnee and Delaware between May 1763 and April 1764, reported to Captain William Grant of the 42nd Regiment "that the Small pox has been very general & raging amongst the Indians since last spring and that 30 or 40 Mingoes, as many Delawares and some Shawneese Died all of the Small pox since that time, that it still continues amongst them".[36]

In the mid to late nineteenth century, at a time of increasing European-American travel and settlement in the West, at least four different epidemics broke out among the Plains tribes between 1837 and 1870.[6] When the Plains tribes began to learn of the "white man’s diseases", many intentionally avoided contact with them and their trade goods. But the lure of trade goods such as metal pots, skillets, and knives sometimes proved too strong. The Indians traded with the white newcomers anyway and inadvertently spread disease to their villages.[37] In the late 19th century, the Lakota Indians of the Plains called the disease the "rotting face sickness."[15][37]

The 1862 Pacific Northwest smallpox epidemic, which was brought from San Francisco to Victoria, devastated the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast, with a death rate of over 50% for the entire coast from Puget Sound to Southeast Alaska.[38] In some areas the native population fell by as much as 90%.[39][40] That the Colony of Vancouver Island and the Colony of British Columbia could have prevented the epidemic but chose not to, and in some ways facilitated the epidemic, has caused some historians to describe the epidemic as an example of deliberate genocide.[39][41]

Effect on population numbers[]

Many Native American tribes suffered high mortality and depopulation, averaging 25–50% of the tribes' members lost to disease. Additionally, some smaller tribes neared extinction after facing a severely destructive spread of disease.[6]

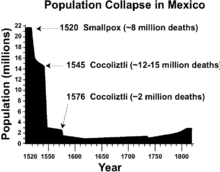

A specific example was what followed Cortés' invasion of Mexico. Before his arrival, the Mexican population is estimated to have been around 25 to 30 million. Fifty years later, the Mexican population was reduced to 3 million, mainly by infectious disease. A 2018 study by Koch, Brierley, Maslin and Lewis concluded that an estimated "55 million indigenous people died following the European conquest of the Americas beginning in 1492."[42] By 1700, fewer than 5,000 Native Americans remained in the southeastern coastal region of the United States.[8] In Florida alone, an estimated 700,000 Native Americans lived there in 1520, but by 1700 the number was around 2,000.[8]

Some 21st-century climate scientists have suggested that a severe reduction of the indigenous population in the Americas and the accompanying reduction in cultivated lands during the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries may have contributed to a global cooling event known as the Little Ice Age.[42][43]

The loss of the population was so high that it was partially responsible for the myth of the Americas as "virgin wilderness." By the time significant European colonization was underway, native populations had already been reduced by 90%. This resulted in settlements vanishing and cultivated fields being abandoned. Since forests were recovering, the colonists had an impression of a land that was an untamed wilderness.[44]

Disease had both direct and indirect effects on deaths. High mortality meant that there were fewer people to plant crops, hunt game, and otherwise support the group. Loss of cultural knowledge transfer also affected the community as vital agricultural and food-gathering skills were not passed on to survivors. Missing the right time to hunt or plant crops affected the food supply, thus further weakening the community and making it more vulnerable to the next epidemic. Communities under such crisis were often unable to care for the disabled, elderly, or young.[8]

In summer 1639, a smallpox epidemic struck the Huron natives in the St. Lawrence and Great Lakes regions. The disease had reached the Huron tribes through French colonial traders from Québec who remained in the region throughout the winter. When the epidemic was over, the Huron population had been reduced to roughly 9000 people, about half of what it had been before 1634.[45] The Iroquois people, generally south of the Great Lakes, faced similar losses after encounters with French, Dutch and English colonists.[8]

During the 1770s, smallpox killed at least 30% of the West Coast Native Americans.[46] The smallpox epidemic of 1780–1782 brought devastation and drastic depopulation among the Plains Indians.[47]

By 1832, the federal government of the United States established a smallpox vaccination program for Native Americans.[48] The Commissioner of Indian Affairs in 1839 reported on the casualties of the 1837 Great Plains smallpox epidemic: "No attempt has been made to count the victims, nor is it possible to reckon them in any of these tribes with accuracy; it is believed that if [the number 17,200 for the upper Missouri River Indians] was doubled, the aggregate would not be too large for those who have fallen east of the Rocky Mountains."[49]

Historian David Stannard asserts that by "focusing almost entirely on disease ... contemporary authors increasingly have created the impression that the eradication of those tens of millions of people was inadvertent—a sad, but both inevitable and "unintended consequence" of human migration and progress." He says that their destruction "was neither inadvertent nor inevitable," but the result of microbial pestilence and purposeful genocide working in tandem.[50] Historian Andrés Reséndez says that evidence suggests "among these human factors, slavery has emerged as a major killer" of the indigenous populations of the Caribbean between 1492 and 1550, rather than diseases such as smallpox, influenza and malaria.[51]

Disability[]

Epidemics killed a high portion of people with disabilities and also resulted in numerous people with disabilities. The material and societal realities of disability for Native American communities were tangible.[8] Scarlet fever could result in blindness or deafness, and sometimes both.[8] Smallpox epidemics led to blindness and depigmented scars. Many Native American tribes prided themselves in their appearance, and the resulting skin disfigurement of smallpox deeply affected them psychologically. Unable to cope with this condition, tribe members were said to have committed suicide.[52]

Noncommunicable diseases[]

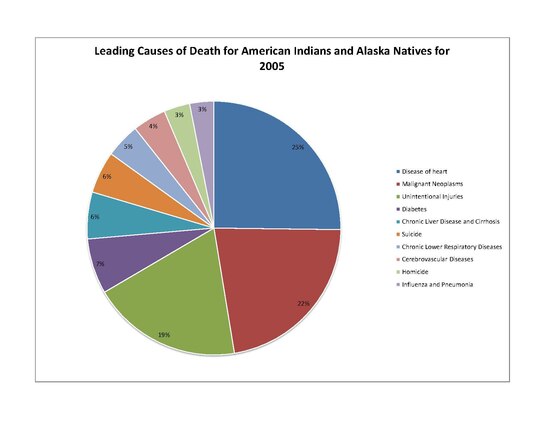

Native Americans share many of the same health concerns as their non-Native American, United States citizen counterparts. For instance, Native Americans' leading causes of death include "heart disease, cancer, unintentional injuries (accidents), diabetes, and stroke". Other health concerns include "high prevalence and risk factors for mental health and suicide, obesity, substance use disorder, sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), teenage pregnancy, liver disease, and hepatitis." The leading causes of death for Native Americans include the following: heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and chronic liver disease / cirrhosis.[53][54] Overall, Native American life expectancy at birth (as of 2008) is 73.7 years, 4.4 years shorter than the United States average.[55]

Though these diseases are also prevalent among non-Native Americans, some present a much greater threat to Native Americans' health.[56] American Indians and Alaska Natives die at greater rates from: chronic liver disease and cirrhosis, diabetes mellitus, unintentional injuries, assault/homicide, intentional self-harm/suicide, and chronic lower respiratory diseases.[57] These discrepancies in disease patterns vary significantly among diseases, but have a significant effect on the population.[citation needed]

The genetic composition of Native Americans and clans can have an influence on many diseases and their continuing presence.[dubious ] The commonly lower socioeconomic status limits the ability of many to receive adequate health care and make use of preventive measures. Also, certain behaviors that take place commonly in the Native American culture can increase risk of disease.[58] When the period of tribal termination in the 20th century occurred, some tribes that were terminated could no longer afford to keep their hospitals open.[59]

In the early 21st century, Native Americans were documented as having higher rates of tobacco use than white, Asian, or black communities. Native American men are about as likely to be moderate to heavy drinkers as white men, but about 5–15% more likely to be moderate to heavy drinkers than black or Asian men. Native Americans are 10% less likely to be at a healthy weight than white adults, and 30% less likely to be at a healthy weight than Asian adults. On a similar note, they have far greater rates of obesity, and were also less likely to engage in regular physical activity than white adults.[60]

Data collected by means of secondary sources, such as the US Census Bureau and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Center for Health Statistics, showed that from 1999 to 2009, Alaska Natives and Native Americans had high mortality rates from infectious diseases when compared to the mortality rate of white Americans. Alaska natives from the age groups 0–19 and 20–49 had death rates 4 to 5 times higher than compared to whites. Native Americans from the 20–49 age group in the Northern Plains were 4 to 5 times more likely to die to infectious diseases than whites. Native American and Alaska Natives were 13 times more likely to contract tuberculosis than whites.[citation needed]

Native Americans were at least twice as likely to have unmet medical needs due to cost. They were much less likely to have seen a dentist within the last five years compared with white or Asian adults, putting them at risk for gingivitis and other oral diseases. Native American/ Alaska Natives face high rates of health disparity compared to other ethnic groups.[61]

Heart disease[]

The leading cause of death of Native Americans is heart disease. In 2005, 2,659 Native Americans died of this cause. Heart disease occurs in Native American populations at a rate 20 percent greater than all other United States races. Additionally, the demographic of Native Americans who die from heart disease is younger than other United States races, with 36% dying of heart disease before age 65.[62] The highest heart disease death rates are located primarily in South Dakota and North Dakota, Wisconsin, and Michigan.[63]

Heart disease among Native Americans is due not only to diabetic complications, but also to higher rates of hypertension. Native American populations have been documented as being more likely to have high blood pressure than other groups, such as white European Americans.[64] Some studies associate the exposure to stress and trauma to an increased rate of heart disease. It has been documented in Native American populations that adverse childhood experiences, which are significantly more common in the Native American demographic, have a positively linear relationship with heart disease, as well an increasing influence on symptoms of heart disease.[65]

Cancer[]

Cancer is documented among Native Americans. The rates of certain types of cancer exceed that of the general population of the United States. For instance, in 2001–05 Native American males were twice as likely to have liver cancer than in white males. Women are 2.4 times as likely to contract and die from liver cancer as their white counterparts. Rates of alcohol use disorder of Native Americans are greater than in the general population.[66]

Stomach cancer was 1.8 times more common in Native American males than white males, and was twice as likely to be fatal. Other cancers, such as kidney cancer, are more common among Native American populations. But overall cancer rates are lower among Native Americans than among the white population of the United States. For cancers that are more prevalent in Native Americans than the white United States population, death rates are higher.[66]

Diabetes[]

Diabetes has posed a significant health risk to Native Americans. Type I diabetes is rare among Native Americans. Type II diabetes is a much more significant problem; it is the type of diabetes discussed in the remainder of this section. Diabetes began to occur at higher rates among Native Americans in the middle of the twentieth century and has increased into what is called an epidemic. This time frame relates to generations having grown up on reservations, and, in some cases, adopting mainstream food and cultural patterns. They were largely prevented from following their traditional patterns of hunting and gathering, and they changed their traditional eating patterns.[67] About 16.3% of Native American adults have been diagnosed with diabetes.[68] Type two diabetes and its complications have become chronic illnesses within Native American and Alaska Native communities. Native Americans and Alaska Natives have high rates of end-stage renal disease, which is mainly driven by, and directly correlates with, the increase in diabetes within their communities.[69]

Native Americans are about 2.8 times more likely to have Type II diabetes than whites of comparable age.[citation needed] The rates of diabetes among Native Americans continue to rise. from 1990 to 1998, the rate of diabetes increased 65% among the Native American population. This is very significant growth, and this growth continues in the present day.[70]

The highest rates of diabetes in the world are found among a Native American tribe. The Pima tribe of Arizona took part in a research study on diabetes which documented diabetes rates within the tribe. This study found that the Pimas had diabetes rates 13 times that of population of Rochester, Minnesota, which is predominately European American in ethnicity. Diabetes was documented in over one third of the Pima from ages 35–44, and in over sixty percent of those over 45 years of age.[71]

There are multiple factors contributing to the prevalence of diabetes among Native Americans:

- Genetic predisposition

- Native Americans with the "least genetic admixture with other groups"[70] have been found to be at a higher risk of developing diabetes. the genetic makeup of the American Indian allowed their bodies to store energy for use in times of famine. When food was plentiful, their bodies stored excess carbohydrates through an exaggerated secretion of insulin called hypersulinemia, and were able to use this stored energy when food was scarce. When feast or famine was no longer an issue, and food was always plentiful, with modern, high caloric foods, their bodies may not have been able to handle the excess fat and calories, resulting in type II diabetes.[72]

- Obesity

- Obesity is a significant health problem for Native Americans, as they are 1.6 times more likely to be obese than white Americans.[56] Native Americans are as likely as black adults to be obese.[61] Obesity is known as a general causative factor of diabetes, and is related to the changes if diet as noted above.

- Low birth weight

- The correlation between low birth weight and increased risk of diabetes has been documented in Native American populations.[70]

- Diet

- Changes in Native American diets have been associated with the increase in diabetes, as more high calorie and high fat foods are consumed, replacing the traditionally agriculturally driven diet.[73] Some tribes have begun programs to encourage their people to return to traditional ways to include growing, preparing, and eating traditional foods.

Several federal agencies are also trying to help. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has also encouraged this approach; in 2013, it produced a public service announcement (PSA), in which Cherokee actors discussed diabetes, and the significance of diet on their increased risk.[74] In the early 21st century, such agencies as the IHS (part of the U.S. Public Health Svc.) & the Division of Diabetes Treatment and Prevention (DDTP) have offered 19 diabetes programs, 12 control officers, and 399 grant programs such as SDPI (Special Diabetes program for Indians), aimed at aiding Native Americans to abolish diabetes for good.[75]

Diabetes' effects[]

The prevalence of diabetes has resulted in related health complications, such as end-stage renal disease.[69] Each of these is more prevalent in the Native American population.[76] Diabetes has increased the rate of premature death of Native Americans by vascular disease, especially among those diagnosed with diabetes later in life. It has been reported among the Pima Tribe to cause elevated urinary albumin excretion. Native Americans with diabetes have a significantly higher rate of heart disease than those without diabetes. Cardiovascular disease is the "leading underlying cause of death in diabetic adults" in Native Americans.[73]

Diabetes can cause nephropathy, leading to renal function deterioration, failure, and disease. Prior to the increase in cardiovascular disease among diabetic Native Americans, renal disease was the leading cause of death for this population. Another complication documented in diabetic Native Americans, as well as other diabetic populations, is retinopathy, causing the loss of sight.[73]

Because of vascular and nerve damage from diabetes, Native Americans suffer a higher rate of lower extremity amputations than European Americans. In studies of the Pima tribes, those with diabetes were also found to have much higher prevalence of periodontal disease, and higher rates of bacterial and fungal infection. For instance, "diabetic Sioux (Lakota people) Tribes were four times as likely to have tuberculosis as those without diabetes."[73]

Native Americans with diabetes have a death rate three times higher than those in the non-Native population. Diabetes can shorten a person's life by approximately 15 years.[68] As of 2012, diabetes was not the leading cause of death for Native Americans but contributed significantly to the top leading causes of death.[53]

The barriers for Native Americans and Alaskan Natives to receive proper health care include the isolated locations of some tribes, and social isolation related to poverty. Travel to health facilities can be too difficult, given distance, hazardous roads, high rates of poverty, and too few staff in hospitals near reservations. Diabetes is the primary cause of end-stage renal disease. Dialysis treatments and kidney transplants remain the most effective methods of treatment, but distance limits access to the first, as noted above. In addition, Native people are documented as having to wait longer for organ transplants than white people.[69]

Stroke[]

Stroke is the sixth-leading cause of death in the Native American population. Native Americans are sixty percent more likely than white adults in the United States to have a stroke. Native American women have double the rate of stroke of white women. About 3.6% of Native American and Alaska Native men and women over 18 have a stroke.[77] The stroke death rate of Native Americans and Alaska Natives is 14 percent greater than among all races.[78]

Psychosocial problems[]

Suicide[]

Native Americans face issues of depression and the highest rate suicide rate of any ethnic group in the United States. In 2009 suicide was the leading cause of death among Native Americans and Native Alaskans between the ages of 10 and 34.[79] 75% of deaths among Native Americans and Native Alaskans over the age of 10 are due to unintentional injury, homicide, and suicide.[79] Suicide rates among Native American youths are significantly higher than among white youths.[79] The head of the IHS, Mary L. Smith, says[when?] that her agency is focusing on mental health issues in Native American communities. Because of numerous suicides among teens on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, it has been designated as a Promise Zone and the government is sending extra help.[80]

A British Columbia study, published in 2007, reported an inverse correlation between Indigenous youth suicide and use of their heritage language. Language use is considered a cultural continuity factor, and it was more highly correlated to youth suicide than six other such cultural factors. Those bands that had higher rates of indigenous language use had lower rates of suicide. Since the late 20th century, numerous tribes have undertaken language revitalization programs in order to maintain their cultures. This study indicates such language use can also have positive effects on teens' mental health. The study recorded suicides among bands with higher use and those with lower use of indigenous languages. Communities with lesser language knowledge estimated 96.59 suicides per 100,000 individuals; the bands with greater language knowledge estimated 13 suicides per 100,000 people. Indigenous youths’ mental health can be affected by the community's use of Indigenous language.[81]

Alcohol use disorder[]

Another significant concern in Native American health is alcohol use disorder. From 2006 to 2010, alcohol-attributed deaths accounted for 11.7 percent of all Native American deaths, more than twice the rates of the general U.S. population. The median alcohol-attributed death rate for Native Americans (60.6 per 100,000) was twice as high as the rate for any other racial or ethnic group.[82] Alcohol use disorder is often approached using the disease model of addiction, with biological, neurological, genetic, and environmental sources of origin.[83] This model has been challenged by research showing that Native American behavior is frequently affected by trauma resulting from domestic violence, racial discrimination, poverty, homelessness, historical trauma, disenfranchised grief, and internalized oppression.[84] Statistically, the incidence of alcohol use disorder among survivors of trauma is significantly elevated, with survivors of physical, emotional and sexual abuse in childhood having the highest rates of alcohol use disorder.[85][86]

However, at least one recent study refutes the belief that Native Americans drink more than white Americans. Analysis of data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) from 2009 to 2013 revealed that Native Americans compared to whites had lower or comparable rates across the range of alcohol measures examined. The survey included responses from 171,858 whites compared to 4,201 Native Americans. The majority (59.9%) of Native Americans abstained from drinking alcohol, whereas less than half (43.1%) of the white population surveyed abstained. Approximately 14.5% of Native Americans were light/moderate-only drinkers, versus 32.7% of whites. Native American and white binge drinking (5+ drinks on an occasion 1-4 days during the past month) estimates were similar: 17.3% and 16.7%, respectively. The two populations' heavy drinking (5+ drinks on an occasion 5+ days in the past month) estimates were also similar: 8.3% and 7.5%, respectively.[87] Nonetheless, Native Americans may be more vulnerable to higher risks associated with drinking because of lack of access to health care, safe housing and clean water.[citation needed]

After colonial contact, white drunkenness was interpreted by whites as the misbehavior of an individual. Native drunkenness was interpreted in terms of the inferiority of a race. What emerged was a set of beliefs known as "firewater myths" that misrepresented the history, nature, sources and potential solutions to Native alcohol problems.[88][89] These myths claim that:

- American Indians have an inborn, insatiable appetite for alcohol.[84]

- American Indians are hypersensitive to alcohol (cannot “hold their liquor”) and are inordinately vulnerable to addiction to alcohol.

- American Indians are inordinately prone to violence when intoxicated.

- These very traits produced immediate, devastating effects when alcohol was introduced to Native tribes via European contact.

- The solutions to alcohol problems in Native communities lie in resources outside these communities.

Scientific literature has debunked many of these myths by documenting the wide variability of alcohol problems across and within Native tribes and the very different response that certain individuals have to alcohol as opposed to others.[90][91]

The 2012–2013 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III (NESARC-III) found that 19.2% of Native Americans surveyed had had an alcohol use disorder during the previous twelve months, and 43.4% had had an alcohol use disorder at some time during their lives (compared to 14.0% and 32.6% of whites, respectively).[92] This contrasts sharply with the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health and National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services, which surveyed adolescents and adults receiving treatment and found that 9.7% of Native Americans surveyed had had an alcohol use disorder during the previous twelve months (compared to 6.1% of whites).[93] An analysis of surveys conducted between 2002 and 2016 determined that 34.4% of Native American adults used alcohol in 2016 (down from 44.7% in 2002).[94]

Native American tribes with a higher level of traditional social integration and less pressure to modernize appear to have fewer alcohol-related problems. Tribes in which social interactions and family structure are disrupted by modernization and acculturative stress (i.e. young people leaving the community to find work) have higher rates of alcohol use and misuse. Native Americans living in urban areas have higher rates of alcohol use than those living in rural areas or on reservations, and more Native Americans living on reservations (where cultural cohesion tends to be stronger) abstain altogether from alcohol.[95] Alaska Natives who follow a more traditional lifestyle have reported greater happiness and less frequent alcohol use for coping with stress.[96]

HIV/AIDS[]

HIV and AIDS are growing concerns for the Native American population. The overall percentage of Native Americans diagnosed with either HIV or AIDS within the entire United States population is relatively small. Native American AIDS cases make up approximately 0.5% of the nation's cases, while they account for about 1.5% of the total population.[56]

Native Americans and Alaska Natives rank third in the United States in the rate of new HIV infections.[97] Native Americans, when counted with Alaskan Natives, have a 40% higher rate of AIDS than white individuals. Also, Native American and Alaskan Native women have double the rate of AIDS of white women.[56]

These statistics have multiple suggested causes:

- Sexual behaviors

- Previous studies of high rates of sexually transmitted diseases among Native Americans lead to the conclusion that the sexual tendencies of Native Americans lead to greater transmission[98]

- Illicit drug use

- The use of illicit drugs is documented to be very high among Native Americans, and not only does the involvement of individuals with illicit drugs correlate with greater rates of sexually transmitted disease, but it can facilitate the spread of diseases

- Socio-economic status

- Due to the poverty and lower rates of education, the risk of getting AIDS or any other sexually transmitted disease can be increased indirectly or directly

- Testing and data collection

- Native Americans may have limited access to testing for HIV/AIDS due to location away from certain health facilities; data collected on Native American sexually transmitted diseases may be limited for this same reason as well as for under-reporting and the Native American race being misclassified[98]

- Culture and tradition

- Native American culture is not always welcoming of open discussion of sexually transmitted diseases[97]

Combating disease and epidemics[]

Many initiatives have been put in place to combat Native American disease and improve the overall health of this demographic. One primary example of such initiative by the government is the Indian Health Service which works "to assure that comprehensive, culturally acceptable personal and public health services are available and accessible to Native American and Alaska Native people".[99] There are many other governmental divisions and funding for health care programs relating to Native American diseases, as well as a multitude of programs administered by tribes themselves.[citation needed]

Legislature[]

Healthcare for Native Americans were provided through the Department of War (throughout the 1800s) until it became a focus of the Office of Indian Affairs in the late 1800s. It again switched government agencies in the early 1950s, going under the supervision of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare's Public Health Service (PHS). In 1955, the Indian Health Service division was created, which still enacts the majority of Native American specific healthcare.[100]

The (23 U.S.C. 13) was one of the first formal legislative pieces to allow healthcare to be provided to Native Americans.[100][101]

In the 1970s, more legislation began passing to expand the healthcare access for Native Americans.[citation needed]

Diabetes programs[]

As diabetes is one of the utmost concerns of the Native American population, many programs have been initiated to combat this disease.

Governmental programs[]

One such initiative has been developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Termed the "Native Diabetes Wellness Program", this program began in 2004 with the vision of an "Indian Country free of the devastation of diabetes".[102] To realize this vision, the program works with Native American communities, governmental health institutions, other divisions of the CDC, and additional outside partners. Together they develop health programs and community efforts to combat health inequalities and in turn prevent diabetes. The four main goals of the Native Diabetes Wellness Program are to promote general health in Native communities (physical activity, traditional foods), spread narratives of traditional health and survival in all aspects of life, utilize and evaluate health programs and education, and promote productive interaction with the state and federal governments.[102]

Funding for these efforts is provided by the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, Public Law 105-33, and the Indian Health Service. One successful aim of this program is the Eagle Books series, which are books using animals as characters to depict a healthy lifestyle that prevents diabetes, including embracing physical activity and healthy food. These books were written by Georgia Perez, who worked with the University of New Mexico's Native American Diabetes Project.[103] Other successful efforts include Diabetes Talking Circles to address diabetes and share a healthy living message and education in schools. The Native Diabetes Wellness Program also has worked with tribes to establish food programs that support the "use of traditional foods and sustainable ecological approaches"[102] to prevent diabetes.

The Indian Health Service has also worked to control the diabetes prevalence among Native Americans. The IHS National Diabetes Program was created in 1979 to combat the escalating diabetes epidemic.[104] The current head of the IHS, Mary L. Smith, Cherokee, took the position in March 2016 and had pledged to improve the IHS and focus on comprehensive health care for all the tribes and people covered by the department.[80] A sector of the service is the Division of Diabetes Treatment and Prevention, which "is responsible for developing, documenting, and sustaining clinical and public health efforts to treat and prevent diabetes in Native Americans and Alaska Natives".[104]

This division contains the Special Diabetes Program for Indians, as created by 1997 Congressional legislation. This program receives $150 million a year in order to work on "Community-Directed Diabetes Programs, Demonstration Projects, and strengthening the diabetes data infrastructure".[104] The Community-Directed Diabetes Programs are programs designed specifically for Native American community needs to intervene in order to prevent and treat diabetes. Demonstration Projects "use the latest scientific findings and demonstrate new approaches to address diabetes prevention and cardiovascular risk reduction".[104] Strengthening the diabetes data infrastructure is an effort to attain a greater base of health information, specifically for the IHS electronic health record.[104]

In addition to the Special Diabetes Program for Native Americans, the IHS combats diabetes with Model Diabetes Programs and the Integrated Diabetes Education Recognition Program. There are 19 Model Diabetes Programs which work to "develop effective approaches to diabetes care, provide diabetes education, and translate and develop new approaches to diabetes control".[104] The Integrated Diabetes Education Recognition Program is an IHS program that works towards high-quality diabetes education programs by utilizing a three-staged accreditation scale. Native American programs in healthcare facilities can receive accreditation and guidance to effectively educate the community concerning diabetes self-management.[104]

Tribal programs[]

Many tribes themselves have begun programs to address the diabetes epidemic, which can be specifically designed to address the concerns of the specific tribe. The Te-Moak Tribe of Western Shoshone have created their diabetes program. With this program, they hope to promote healthy lifestyles with exercise and modified eating and behavior. The means of achieving these ends including "a Walking Club, 5 a Day Fruits and Vegetable, Nutrition teaching, Exercise focusing, 28 day to Diabetes Control, and Children's Cookbook".[105] Additionally, the Te-Moak tribe has constructed facilities to promote healthy lifestyles, such as a center to house the diabetes program and a park with a playground to promote active living.[105]

The Meskwaki Tribe of the Mississippi has also formed diabetes program to provide for the tribe's people. The Meskwaki Tribe facilitates their program to eliminate diabetes as a health concern through prevention and control of complications. The program has a team mentality, as community, education and clinical services are all involved as well as community organizations and members.[106]

There are many facets of this diabetes program, which include the distribution of diabetes information. This is achieved through bi-weekly articles in the Meskwaki Times educating the population about diabetes prevention and happenings in the program and additional educational materials available about diabetes topics. Other educational is spread through nutrition and diabetes classes, such as the Diabetes Prevention Intensive Lifestyle Curriculum Classes, and events like health fairs and walks. Medical care is also available. This includes bi-weekly diabetes clinics, screenings for diabetes and related health concerns and basic supplied.[106]

HIV-AIDS programs[]

Multiple programs exist to address the HIV and AIDS concerns for Native Americans. Within the Indian Health Service, an HIV/AIDS Principal Consultant heads an HIV/AIDS program. This program involves many different areas to address "treatment, prevention, policy, advocacy, monitoring, evaluation, and research".[107] They work through many social outputs to prevent the masses from the epidemic and enlist the help of many facilities to spread this message.[107]

The Indian Health Service also works with Minority AIDS Initiative to use funding to establish AIDS projects. This funding has been used to create testing, chronic care, and quality care initiatives as well as training and camps.[108] The Minority AIDS Initiative operates through the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program, under the Public Health Service Act. This is in recognition of the disproportionate impact of HIV/AIDS on racial and ethnic minorities.[109]

There has also been a National Native HIV/AIDS Awareness Day held on March 20 for Native Americans, Alaska Natives, and Native Hawaiians, with 2009 marking its third year. This day is held to:

- encourage Native people to get educated and to learn more about HIV/AIDS and its impact in their community;

- work together to encourage testing options and HIV counseling in Native communities; and

- help decrease the stigma associated with HIV/AIDS.[110]

This day takes place across the United States with many groups working in coordination, groups like the CDC and the National Native Capacity Building Assistance Network. By putting out press releases, displaying posters, and holding community events, these groups hope to raise awareness of the HIV/AIDS epidemic.[110]

Heart disease and stroke programs[]

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention contain a Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention, which collects data and specifically releases information to form policy for Native Americans. They have identified many areas in which lifestyles of Native Americans need to be changed in order to greatly decrease the prevalence of heart disease and stroke.[78] One major concern to prevent is diabetes, which directly relates to the presence of heart disease. Many general health concerns also need to be addressed, according to the CDC's observations, including moderating alcohol use, eliminating tobacco use, maintaining health body weight, regularizing physical activity, diet, and nutrition, preventing and controlling high blood cholesterol, and preventing and controlling high blood pressure.[78]

The Indian Health Service works in collaboration with the University of Arizona College of Medicine to maintain the Native American Cardiology Program. This is a program that acknowledges the changes in lifestyle and economics in the recent past which have ultimately increased the prevalence of heart attacks, coronary disease, and cardiac deaths. The Native American Cardiology Program prides itself in its cultural understanding, which allows it to tailor health care for its patients.[111]

The program has many bases but has placed an emphasis on providing care to remote, rural areas in order for more people to be cared for. The Native American Cardiology Program's telemedicine component allows for health care to be made more accessible to Native Americans. This includes interpreting medical tests, offering specialist input and providing triage over the phone. The Native American Cardiology Program also has educational programs, such as lectures on cardiovascular disease and its impact, and outreach programs.[111]

Alcohol treatment and prevention programs[]

SAMHSA's Office of Tribal Affairs and Policy[]

The Office of Tribal Affairs and Policy (OTAP) serves as primary point of contact between the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and tribal governments, tribal organizations, and federal agencies on behavioral health issues that impact tribal communities.[112] OTAP supports SAMHSA's efforts to implement the Tribal Law and Order Act (TLOA) of 2010 and the National Tribal Behavioral Health Agenda.[113] The Office of Indian Alcohol and Substance Abuse (OIASA),[114] an organizational component of OTAP, coordinates federal partners and provides tribes with technical assistance and resources to develop and enhance prevention and treatment programs for substance use disorders, including alcohol.[citation needed]

Indian Health Services[]

The Alcohol and Substance Abuse Program (ASAP) is a program for American Indian and Alaska Native individuals to reduce the incidence and prevalence of alcohol and substance use disorders. These programs are administered in tribal communities, including emergency, inpatient and outpatient treatment and rehabilitation services for individuals covered under Indian Health Services.[115] It addresses and treats alcohol use disorder from a disease model perspective.

Tribal Action Plan[]

The Indian Alcohol and Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act of 1986[116] was updated in 2010 to make requirements that the Office of Indian Alcohol and Substance Abuse (OIASA), a subdivision of SAMHSA, is to work with federal agencies to assist Native American communities in developing a Tribal Action Plan (TAP).[117] The TAP coordinates resources and funding required to help mitigate levels of alcohol and substance abuse among the Native American population, as specified in the Indian Alcohol and Substance Abuse Memorandum of Agreement of August 2011, and executed by OIASA.[citation needed]

See also[]

- Modern social statistics of Native Americans

- Indian Health Service

- Little Ice Age

- New World Syndrome

- Alcohol and Native Americans

- Native American Health Center

- Environmental racism

- Impact of Old World diseases on the Maya

- History of smallpox in Mexico

- 1918 Spanish flu pandemic

- COVID-19 pandemic in the Navajo Nation

- Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Native American tribes and tribal communities

General:

- Native Americans in the United States

- Population history of indigenous peoples of the Americas

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Martin, Debra L; Goodman, Alan H (January 2002). "Health conditions before Columbus: paleopathology of native North Americans". Western Journal of Medicine. 176 (1): 65–68. doi:10.1136/ewjm.176.1.65. ISSN 0093-0415. PMC 1071659. PMID 11788545.

- ^ Crosby, Alfred W. (1976), "Virgin Soil Epidemics as a Factor in the Aboriginal Depopulation in America", The William and Mary Quarterly, Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 33 (2): 289–299, doi:10.2307/1922166, JSTOR 1922166, PMID 11633588

- ^ Mary Smith, "Native Americans: A Crisis in Health Equity," Human Rights Magazine, Vol. 43, No. 3: The State of Healthcare in the United States; 1 Aug 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Francis, John M. (2005). Iberia and the Americas culture, politics, and history: A Multidisciplinary Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO.

- ^ Bos, Kirsten I.; Harkins, Kelly M.; Herbig, Alexander; Coscolla, Mireia; et al. (20 August 2014). "Pre-Columbian mycobacterial genomes reveal seals as a source of New World human tuberculosis". Nature. 514 (7523): 494–7. Bibcode:2014Natur.514..494B. doi:10.1038/nature13591. PMC 4550673. PMID 25141181.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Waldman, Carl (2009). Atlas of the North American Indian. New York: Checkmark Books. p. 206.

- ^ Rossi, Ann (2006). Two Cultures Meet: Native American and European. National Geographic Society. pp. 31–32. ISBN 978-0-7922-8679-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Nielsen, K.E. (2012). A Disability History of the United States. Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-2204-7.

- ^ Rodrigo Barquera, Johannes Krause, AJ Zeilstra, Petra Mader, "Slavery entailed the spread of epidemics," Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, May 09, 2020

- ^ Tine Huyse, "The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade and the Introduction of Human Diseases: The Case of Schistosomiasis," Africa Atlanta 2014 Publications, Ivan Allen College of Liberal Arts, Georgia Institute of Technology, May 2014

- ^ Austin Alchon, Suzanne (2003). A Pest in the Land: New World Epidemics in a Global Perspective. University of New Mexico Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-8263-2871-7. Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- ^ Hays, J. N.. Epidemics and Pandemics: Their Impacts on Human History. United Kingdom: ABC-CLIO, 2005.

- ^ Vogel, Virgil J. American Indian Medicine. University of Oklahoma Press, 1970.

- ^ John Phillip. A law of blood; the primitive law of the Cherokee nation. New York: Northern Illinois University Press, 1970.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Robertson, R. G. Rotting Face: Smallpox and the American Indian. Caxton Press, 2001.ISBN 0870044974

- ^ Lyon, William S. (1998). Encyclopedia of Native American Healing. W. W. Norton and Company. ISBN 978-0-393-31735-0.

- ^ Daniel E. Moerman, Native American Ethnobotany, Timber Press, 1998 ISBN 0881924539

- ^ Dutch Children's Disease Kills Thousands of Mohawks Archived 2007-12-17 at the Wayback Machine. Paulkeeslerbooks.com

- ^ Duffy, John (1951). "Smallpox and the Indians in the American Colonies". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 25 (4): 324–341. PMID 14859018.

- ^ Ramenofsky, Ann Felice. Vectors of Death: The Archaeology of European Contact. University of New Mexico Press, 1987.

- ^ McCullough, John: The Captivity of John McCullough/ Personally written after eight years of captivity. Archived 2014-04-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ecuyer, Simeon: Fort Pitt and letters from the frontier (1892)Journal of Captain Simeon Ecuyer, Entry June 2, 1763

- ^ McCullough, John: http://The Captivity of John McCullough Personally written after eight years of captivity. Archived 2014-04-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dixon, David, Never Come to Peace Again: Pontiac's Uprising and the Fate of the British Empire in North America (pg. 155)

- ^ Hanna, Charles A.: The wilderness trail: or, the ventures and adventures of the Pennsylvania traders on the Allegheny path, with some new annals of the old West, and the records of some strong men and some bad ones (1911) pg.366

- ^ Ewald, Paul W. (2000). Plague Time: How Stealth Infections Cause Cancer, Heart Disease, and Other Deadly Ailments. New York: Free. ISBN 978-0-684-86900-1.

- ^ Ecuyer, Simeon: Fort Pitt and letters from the frontier (1892). Captain Simeon Ecuyer's Journal: Entry of June 24,1763

- ^ Fenn, Elizabeth A. Biological Warfare in Eighteenth-Century North America: Beyond Jeffery Amherst Archived 2015-04-03 at the Wayback Machine; The Journal of American History, Vol. 86, No. 4, March, 2000

- ^ "BBC – History – Silent Weapon: Smallpox and Biological Warfare". Retrieved 2008-01-02.

- ^ Elizabeth A. Fenn. "Biological Warfare in Eighteenth-Century North America: Beyond Jeffery Amherst," The Journal of American History, Vol. 86, No. 4 (Mar., 2000), pp. 1552–1580

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ranlet, P (2000). "The British, the Indians, and smallpox: what actually happened at Fort Pitt in 1763?". Pennsylvania History. 67 (3): 427–441. PMID 17216901.

- ^ Barras, V.; Greub, G. (June 2014). "History of biological warfare and bioterrorism". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 20 (6): 497–502. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12706. PMID 24894605.

- ^ King, J. C. H. (2016). Blood and Land: The Story of Native North America. Penguin UK. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-84614-808-8.

- ^ Barras, V.; Greub, G. (June 2014). "History of biological warfare and bioterrorism" (PDF). Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 20 (6): 497–502. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12706. PMID 24894605.

However, in the light of contemporary knowledge, it remains doubtful whether his hopes were fulfilled, given the fact that the transmission of smallpox through this kind of vector is much less efficient than respiratory transmission, and that Native Americans had been in contact with smallpox >200 years before Ecuyer's trickery, notably during Pizarro's conquest of South America in the 16th century. As a whole, the analysis of the various 'pre-micro-biological' attempts at BW illustrate the difficulty of differentiating attempted biological attack from naturally occurring epidemics.

- ^ Medical Aspects of Biological Warfare. Government Printing Office. 2007. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-16-087238-9.

In retrospect, it is difficult to evaluate the tactical success of Captain Ecuyer's biological attack because smallpox may have been transmitted after other contacts with colonists, as had previously happened in New England and the South. Although scabs from smallpox patients are thought to be of low infectivity as a result of binding of the virus in fibrin metric, and transmission by fomites has been considered inefficient compared with respiratory droplet transmission.

- ^ Burke, James P., Pioneers of Second Fork (pgs. 19–22)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Marshall, Joseph (2005) [2004]. The Journey of Crazy Horse, A Lakota History. Penguin Books.

- ^ Lange, Greg. "Smallpox Epidemic of 1862 among Northwest Coast and Puget Sound Indians". HistoryLink. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ostroff, Joshua (August 2017). "How a smallpox epidemic forged modern British Columbia". Maclean's. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ Boyd, Robert; Boyd, Robert Thomas (1999). "A final disaster: the 1862 smallpox epidemic in coastal British Columbia". The Coming of the Spirit of Pestilence: Introduced Infectious Diseases and Population Decline Among Northwest Coast Indians, 1774–1874. University of British Columbia Press. pp. 172–201. ISBN 978-0-295-97837-6. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ Swanky, Tom (2013). The True Story of Canada's "War" of Extermination on the Pacific – Plus the Tsilhqot'in and other First Nations Resistance. Dragon Heart Enterprises. pp. 617–619. ISBN 978-1-105-71164-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Koch, Alexander; Brierley, Chris; Maslin, Mark M.; Lewis, Simon L. (2019). "Earth system impacts of the European arrival and Great Dying in the Americas after 1492". Quaternary Science Reviews. 207: 13–36. Bibcode:2019QSRv..207...13K. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.12.004.

- ^ Degroot, Dagomar (2019). "Did Colonialism Cause Global Cooling? Revisiting an Old Controversy". Historical Climatology.

- ^ Denevan, William M. "The pristine myth: the landscape of the Americas in 1492." Annals of the Association of American Geographers 82, no. 3 (1992): 369-385.

- ^ Bruce Trigger. Natives and Newcomers: Canada’s “Heroic Age” Reconsidered. (Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1985), 588–589.

- ^ Smallpox, The Canadian Encyclopedia

- ^ Houston CS, Houston S (2000). "The first smallpox epidemic on the Canadian Plains: In the fur-traders' words". Can J Infect Dis. 11 (2): 112–5. doi:10.1155/2000/782978. PMC 2094753. PMID 18159275.

- ^ Lewis Cass and the Politics of Disease: The Indian Vaccination Act of 1832. Muse.jhu.edu. Retrieved on 2011-12-06.(registration required)

- ^ The Effect of Smallpox on the Destiny of the Amerindian; Esther Wagner Stearn, Allen Edwin Stearn; University of Minnesota; 1945; Pgs. 13-20, 73-94, 97

- ^ David E. Stannard (1993-11-18). American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World. Oxford University Press, USA. p. xii. ISBN 978-0-19-508557-0.

- ^ Reséndez, Andrés (2016). The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-547-64098-3.

- ^ Watts, Sheldon (1999). Epidemics and History: Disease, Power and Imperialism. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08087-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Native American & Alaska Native (AI/AN) Populations". Office of Minority Health and Health Disparities, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. November 30, 2010. Archived from the original on 2013-11-22. Retrieved December 4, 2013.

- ^ Barnes, P.M., P.F. Adams, and E. Powell-Griner. (2010). Health Characteristics of the Native American or Alaska Native Adult Population: United States, 2004–2008. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics.

- ^ Indian Health Service. Trends in Indian Health: 2014 Edition. p. 143.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Native American/Alaska Native Profile – The Office of Minority Health." Home Page – The Office of Minority Health. 31 July 2009. Web. 01 Oct. 2009.<http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/templates/browse.aspx?lvl=2&lvlID=52 Archived 2012-09-13 at the Wayback Machine>

- ^ Indian Health Service (January 2013). "Disparities". Newsroom. Retrieved June 10, 2017.

- ^ Young, T. Kue (1997). "Recent Health Trends in the Native Americans' Population". Population Research and Policy Review. 16: 147–67. doi:10.1023/A:1005793131260. S2CID 67979174.

- ^ Deloria, Vine (1988). Custer Died For Your Sins, An Indian Manifesto. New York: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-8061-2129-1.

- ^ Barnes, Patricia M. (2005). Vital and Health Statistics: Health Characteristics of the Native American and Alaska Native Adult Population (356th ed.). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- ^ Jump up to: a b 2005. Health Characteristics of the Native Americans and Alaska Native Adult Population: U.S., 19992003 : Advance Data: From Vital and Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Center for Health Statistics;2005 ASI 41468.357;PHS 20051250, No. 356. n.p.:

- ^ "Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention – AIAN Fact Sheet". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. October 9, 2009. Archived from the original on 2010-09-21. Retrieved 2017-09-10.

- ^ (https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/data_statistics/fact_sheets/fs_aian.htm)

- ^ Duyff, Roberta Larson (2006). American Dietetic Association Complete Food and Nutrition Guide. New York: Wiley.

- ^ Bullock, Ann; Ronny A. Bell (2005). "Stress, trauma and coronary heart disease among Native Americans". American Journal of Public Health. 95 (12): 2122–b–2123. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.072645. PMC 1449491. PMID 16257937.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Cancer and Native Americans/Alaska Natives". United States Department of Health and Human Services: Office of Minority Health. June 13, 2012. Archived from the original on 2012-09-13. Retrieved September 7, 2012.

- ^ Edwards, Karethy; Patchell, Beverly (2009). "State of the science: a cultural view of Native Americans and diabetes prevention". Journal of Cultural Diversity. 16 (1): 32–35. PMC 2905172. PMID 20640191.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Division of Diabetes Treatment and Prevention". Indian Health Service. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Narva, Andrew S (2002). "Kidney Disease in Native Americans". Journal of the National Medical Association. 94 (8): 738–42. PMC 2594281. PMID 12152933.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Joslin, Elliott P. (2005). Joslin's diabetes mellitus. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Willkins.

- ^ Mogensen, Carl Erik (2000). The Kidney and Hypertension in Diabetes Mellitus. New York: Springer.

- ^ "Type II Diabetes, the Modern Epidemic of American Indians in the United States". anthropology.ua.edu. Retrieved 2018-05-11.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Ekoé, Jean-Marie; Zimmet, Paul; Williams, Rhys, eds. (2001). The Epidemiology of Diabetes Mellitus: An International Perspective. New York: Wiley. doi:10.1002/0470846429. ISBN 978-0-471-97448-2. S2CID 58513280.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2013-02-27), OUR CULTURES ARE OUR SOURCE OF HEALTH, retrieved May 6, 2016

- ^ McLaughlin, Sue (2010-10-02). "Traditions and Diabetes Prevention: A Healthy Path for Native Americans". Diabetes Spectrum. 23 (4): 272–277. doi:10.2337/diaspect.23.4.272. ISSN 1040-9165.

- ^ Sandefur, Gary D (1996). Changing numbers, Changing needs: Native American demography and public health. National Academy Press. ISBN 978-0-309-17529-6.

- ^ "Stroke and Native Americans/Alaska Natives". Office of Minority Health. Archived from the original on 2009-11-16. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention – AIAN Fact Sheet". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 2009-10-20. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Mental Health – The Office of Minority Health". minorityhealth.hhs.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-05-09. Retrieved May 5, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b kpolisse (April 25, 2016). "New IHS Head Focused on Quality, Accountability". Indian Country Today Media Network.com. Retrieved May 5, 2016.

- ^ Hallett, Darcy; Chandler, Michael; Lalonde, Christopher (2007). "Aboriginal language knowledge and youth suicide" (PDF). Cognitive Development. 22 (3): 392–399. doi:10.1016/j.cogdev.2007.02.001. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- ^ CDC, "Alcohol-Attributable Deaths and Years of Potential Life Lost — 11 States, 2006–2010," MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014 Mar 14; 63(10): 213–216. Published online 2014 Mar 14.

- ^ Matamonasa-Bennett A. "The Poison That Ruined the Nation": Native American Men-Alcohol, Identity, and Traditional Healing. Am J Mens Health. 2017;11(4):1142–1154.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne; Gilio-Whitaker, Dina (2016). "All the Real Indians Died Off": And 20 Other Myths about Native Americans. Beacon Press: Boston, 2016. ISBN 978-0-8070-6265-4.

- ^ Buchwald, D., Tomita, S., Hartman, S., Furman, R., Dudden, M. & Manson, S. M. "Physical abuse of urban Native Americans." Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2000;15, 562-564.

- ^ Amanda Lechner, Michael Cavanaugh, Crystal Blyler. "Addressing Trauma in American Indian and Alaska Native Youth," Research paper developed for the Dept. of Health & Human Services by Mathematica Policy Research, Washington, DC August 24, 2016.

- ^ Cunningham, James K.; Solomon, Teshia A.; Muramoto, Myra L. (2016). "Alcohol use among Native Americans compared to whites: Examining the veracity of the 'Native American elevated alcohol consumption' belief". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 160: 65–75. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.12.015. PMID 26868862.

- ^ Gonzalez VM, Skewes MC. "Association of the firewater myth with drinking behavior among American Indian and Alaska Native college students." Psychol Addict Behav. 2016 Dec; 30(8):838-849. Epub 2016 Oct 13.

- ^ Gonzalez VM, Bravo AJ, Crouch MC, "Endorsement of the 'firewater myth' affects the use of protective behavioral strategies among American Indian and Alaska Native students." Addict Behav. 2019 Jun; 93:78-85. Epub 2019 Jan 22.

- ^ http://www.williamwhitepapers.com/pr/2002AddictionRecoveryinNativeAmerica.pdf Coyhis, D. and White, W. (2002) "Addiction and Recovery in Native America: Lost History, Enduring Lessons." Counselor, 3(5):16-20.

- ^ Coyhis, D.; Simonelli, R. (2008). "The Native American Healing Experience". Substance Use & Misuse. 43 (12–13): 1927–1949. doi:10.1080/10826080802292584. PMID 19016172. S2CID 20769339.

- ^ Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. "Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III." JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):757–766.

- ^ "Behavioral Health Barometer: United States, Volume 4: Indicators, as measured through the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health and National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration." HHS Publication No. SMA–17–BaroUS–16. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2017.

- ^ Table 50: Use of selected substances in the past month among persons aged 12 and over, by age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin: United States, selected years 2002–2016. 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health and National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services.

- ^ Philip A. May, "Overview of Alcohol Abuse Epidemiology for American Indian Populations," in Changing Numbers, Changing Needs: American Indian Demography and Public Health, Gary D. Sandefur, Ronald R. Rindfuss, Barney Cohen, Editors. Committee on Population, Commission on Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education National Research Council. National Academy Press: Washington, D.C. 1996

- ^ Borowsky, I. W., Resnick, M. D., Ireland, M., & Blum, R. W. "Suicide attempts among American Indian and Alaska Native youth: risk and protective factors." Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 1999;153(6), 573–580.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Indian Health Service Fact Sheets". Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "HIV/AIDS among Native Americans and Alaska Natives — Factsheets". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 2009-10-17. Retrieved October 6, 2009.

- ^ "Introduction to IHS by Dr Yvette Roubideaux". Indian Health Service. Archived from the original on 2009-05-09. Retrieved October 9, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Champagne, Duane (2001). The Native North American ALmanac. Farmingtom Hills, MI: Gale Group. pp. 943–945. ISBN 978-0-7876-1655-7.

- ^ "Legislation | About IHS". About IHS. Retrieved 2018-11-04.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "National Diabetes Wellness Program". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved October 9, 2009.

- ^ "Eagle Books | Native Diabetes Wellness Program". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved May 6, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g "Division of Diabetes Treatment and Prevention". Indian Health Service. Retrieved October 9, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Special Diabetes Program". Te-Moak Tribe of Western Shoshone. Retrieved October 13, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Sac & Fox Tribe – Diabetes & Wellness Program". Official Site of the Meskwaki Nation. Archived from the original on 2009-06-30. Retrieved October 13, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "IHS HIV/AIDS Program". Indian Health Service. Archived from the original on 2009-08-25. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- ^ "IHS HIV/AIDS Program Minority AIDS Initiative". Indian Health Service. Archived from the original on 2009-08-25. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- ^ "HRSA – Part F Minority AIDS Initiative". Health Resources and Services Administration. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "2009 National Native HIV/AIDS Awareness Day". National Native American AIDS Prevention Center. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Native American Cardiology Program at UMC". University Medical Center Tucson, Arizona. Archived from the original on 2010-12-01. Retrieved October 14, 2009.

- ^ "SAMHSA's Office of Tribal Affairs". Archived from the original on 2020-07-01. Retrieved 2020-07-02.

- ^ "The National Tribal Behavioral Health Agenda". Archived from the original on 2019-08-16. Retrieved 2020-07-02.

- ^ "Office of Indian Alcohol and Substance Abuse". Archived from the original on 2020-06-30. Retrieved 2020-07-02.

- ^ "Alcohol and Substance Abuse Program: Treatment". Archived from the original on 2020-04-22. Retrieved 2020-07-02.

- ^ "The Indian Alcohol and Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act". Archived from the original on 2019-01-02. Retrieved 2020-07-02.

- ^ ""Tribal Action Plan," Indian Health Service". Archived from the original on 2020-04-01. Retrieved 2020-07-02.

External links[]

- Epidemics

- Indigenous peoples of North America

- Native American health

- Native American history