Northern Society of the Decembrists

This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. (November 2021) |

Northern Society of the Decembrists Северное тайное общество | |

|---|---|

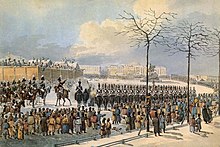

Decembrists at the Senate Square | |

| Leader | Nikita Muravyov |

| Founded | 1821 |

| Dissolved | January 1826 |

| Split from | Union of Prosperity |

| Headquarters | St. Petersburg |

| Ideology | Liberalism Constitutionalism Federalism Abolitionism |

| Political position | Left-wing |

| Movement | Decembrists |

| |

| Part of a series on |

| Liberalism |

|---|

|

|

The Northern Society of the Decembrists (Russian: Северное тайное общество) was formed in St. Petersburg after the dissolution of the Union of Prosperity. Its members participated in the Decembrist revolt.

Formation[]

The Northern Society was formed in St. Petersburg in 1822 from two Decembrist groups headed by Nikita Muravyov and Sergei Trubetskoy.

When the Union of Prosperity was dissolved at the Moscow Congress of its leaders in January 1821, it was decided to create a new organization with four boards: in Moscow, Petersburg, Smolensk and Tulchin. However, none of them were created. Some of the future Decembrists, headed by Pavel Pestel, did not recognize the decision of the Moscow Congress and entered the Southern Society in March 1821.[1] In St. Petersburg, the Northern Society appeared, and its organizational structure was formed in 1822. Members of the society were divided into "convinced" (full-fledged) and "agreeable" (unequal). The governing body was the "Supreme Duma" of three people (originally Nikita Muravyov, Nikolay Turgenev and Yevgeny Obolensky,[2] later - Sergei Trubetskoy, Kondraty Ryleyev and Alexander Bestuzhev). At the beginning of 1825, Ryleyev attracted Pyotr Kakhovsky, who was extremely negative towards the Tsarist autocracy.

The guards officers , , and naval officers , and also took an active part in the Northern Society.

Political views[]

The program document of the "northerners" was the "Constitution" of Nikita Muravyov.[3]

The northern society was more moderate in goals than the southern one. However, the influential radical wing headed by Kondraty Ryleyev, Alexander Bestuzhev, Yevgeny Obolensky, Ivan Pushchin shared the ideas of Pavel Pestel's Russian Truth.[4] In 1824, the latter himself came to St. Petersburg to achieve recognition of his program as common to both societies, which caused a revival in the radical wing of the "northerners". Secretly from the moderate leaders of the Northern Society, the St. Petersburg branch of the Southern Society was formed. As a result, an active discussion unfolded, which led to the fact that both of them made concessions: the "northerners" agreed to establish a republic after the coup, and the "southerners" agreed to convene a Constituent Assembly.[5]

Local historian of Yakutia in his essay Alexander Bestuzhev in Yakutsk quotes the latter's statement:

"[...] the purpose of our conspiracy was to change the government, some wanted a republic in the image of the United States; other constitutional king, as in England; still others wanted, without knowing what, but propagated other people's thoughts. We called these people hands, soldiers and accepted them into the society only for numbers. The head of the Petersburg conspiracy was Ryleyev."

Constitution[]

State structure[]

- The introduction of a constitutional monarchy.[3]

- Formation of a federation of 13 states[3] based not on national, but on the economic characteristics of the regions. "Powers" were tied to the seas or large navigable rivers.

- Separation of powers into legislative, executive and judicial.

- Creation of a bicameral People's Council, elected on the basis of a large property qualification[3] and consisting of the Verkhovna Duma (upper house) and the House of People's Representatives (lower house). The deputies to both chambers were to be elected for 6 years, and every two years a third of the deputies were re-elected. The upper house was elected by 3 deputies from each power and two from the "regions". In the lower one - one deputy from 50,000 male residents.

- The "states" elected Sovereign veche, whose deputies were elected for 4 years and a quarter of them were re-elected annually.

- Executive power belonged to the emperor, who was also the Supreme Commander-in-Chief, who, with the consent of the Supreme Duma, appointed ambassadors, consuls, judges of the supreme court chambers and ministers. The emperor was considered "the first official of the state" and received a large salary - from 8 to 10 million rubles in silver a year. The emperor could maintain his court, but the courtiers in this case were deprived of voting rights, as they were "in service."

Serfdom[]

- Serfdom was abolished, but the possessions of the landowners remained with the old owners.[3]

- The liberated peasants received up to 2 acres of arable land per yard.

Citizens' rights[]

The land question[]

Members of the Society believed that the land should be divided into:

- public - (peasant, state, monastic and half landlord) which is transferred to the peasants free of charge, but without the right to buy and sell;

- private - which is in market circulation.

References[]

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2014, p. 25.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2014, pp. 25–26.

- ^ a b c d e f g Yarmolinsky 2014, p. 26.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2014, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2014, p. 30.

Bibliography[]

- Yarmolinsky, Avrahm (2014) [1956]. Road to Revolution: A Century of Russian Radicalism. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 069161041X. OCLC 890439998.

- Мемуары декабристов. Северное общество / Ред. В. А. Фёдоров. — Москва: МГУ, 1981.�

- 1821 establishments in the Russian Empire

- 1826 disestablishments in the Russian Empire

- Conspiracies

- Decembrists

- Political organizations based in Russia

- Political parties established in 1821

- Political parties disestablished in 1826

- Secret societies in Russia