Political history of the world

| Part of a series on |

| Politics |

|---|

|

|

The political history of the world is the history of the various political entities created by the human race throughout their existence and the way these states define their borders. Throughout history, political entities have expanded from basic systems of self-governance and monarchy to the complex democratic and totalitarian systems that exist today. In parallel, political systems have expanded from vaguely defined frontier-type boundaries, to the national definite boundaries existing today.

Prehistoric era[]

The primate ancestors of human beings already had social and political skills.[1] The first forms of human social organization were families living in band societies as hunter-gatherers.[2]

After the invention of agriculture around the same time (7,000-8,000 BCE) across various parts of the world, human societies started transitioning to tribal forms of organization.[3]

There is evidence of diplomacy between different tribes, but also of endemic warfare.[4] This could have been caused by theft of livestock or crops, abduction of women, or resource and status competition.[5]

Ancient history[]

The early distribution of political power was determined by the availability of fresh water, fertile soil, and temperate climate of different locations.[6] These were all necessary for the development of highly organized societies.[6] The locations of these early societies were near, or benefiting from, the edges of tectonic plates.[7] the Indus Valley Civilization was located next to the Himalayas (which were created by tectonic pressures) and the Indus and Ganges rivers, which deposit sediment from the mountains to produce fertile land.[8] A similar dynamic existed in Mesopotamia, where the Tigris and Euphrates did the same with the Zagros Mountains.[9] Ancient Egypt was helped by the Nile depositing sediments from the East African highlands of its origins, while the Yellow River and Yangtze acted in the same way for Ancient China.[10] Eurasia was advantaged in the development of agriculture by the natural occurrence of domesticable wild grass species and the east-west orientation of the landmass, allowing for the easy spread of domesticated crops.[11] A similar advantage was given to it by half of the world's large mammal species living there, which could be domesticated.[12]

The development of agriculture allowed higher populations, with the newly dense and settled societies becoming hierarchical, with inequalities in wealth and freedom.[13] As the cooling and drying of the climate by 3800 BCE caused drought in Mesopotamia, village farmers began co-operating and started creating larger settlements with irrigation systems.[13] This new water infrastructure in turn required centralised administration with complex social organisation.[13] The first cities and systems of greater social organisation emerged in Mesopotamia, followed within a few centuries by ones at the Indus and Yellow River Valleys.[14] In the cities, the workforce could specialise as the whole population did not have to work for food production, while stored food allowed for large armies to create empires.[14] The first empires were those of Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia.[6] Smaller kingdoms existed in North China Plain, Indo-Gangetic Plain, Central Asia, Anatolia, Eastern Mediterranean, and Central America, while the rest of humanity continued to live in small tribes.[6]

Middle East and the Mediterranean[]

The first states of sorts were those of early dynastic Sumer and early dynastic Egypt, which arose from the Uruk period and Predynastic Egypt respectively at approximately 3000BCE.[15] Early dynastic Egypt was based around the Nile River in the north-east of Africa, the kingdom's boundaries being based around the Nile and stretching to areas where oases existed.[16] Upper and Lower Egypt were unified around 3150 BCE by Pharaoh Menes.[17] This process of consolidation was driven by the crowding of migrants from the expanding Sahara in the Nile delta.[18] Nevertheless, political competition continued within the country between centers of power such as Memphis and Thebes.[17] The prevailing north-east trade winds made it easier to sail up the river, thereby helping the unification of the state.[18] The geopolitical environment of the Egyptians had them surrounded by Nubia in the smaller southern oases of the Nile unreachable by boat, as well as by Libyan warlords operating from the oases around modern-day Benghazi, and finally by raiders across the Sinai and the sea.[19] The country was well defended by natural barriers formed by the Sahara on both sides, though this also limited its ability to expand into a larger empire, mostly remaining a regional power along the Nile (except for a conquest of the Levant in the second millennium BCE).[18] The lack of timber also made it too expensive to build a large navy for power projection across the Mediterranean or Red Seas.[20]

Mesopotamian dominance[]

Mesopotamia is situated between the major rivers of Tigris and Euphrates, and the first political power in the region was the Akkadian Empire starting around 2300 BCE.[21] They were later followed by Sumer, Babylon, and Assyria. They faced competition from the mountainous areas to the north, strategically positioned above the Mesopotamian plains, with kingdoms such as Mitanni, Urartu, Elam, and Medes.[21] The Mesopotamians also innovated in governance by writing the first laws.[21]

A dry climate in the Iron Age caused turmoil as movements of people put pressure on the existing states resulting in the Late Bronze Age collapse, with Cimmerians, Arameans, Dorians, and the Sea Peoples migrating among others.[22] Babylon never recovered following the death of Hammurabi in 1699 BCE.[22] Following this, Assyria grew in power under Adad-nirari II.[23] By the late ninth century BCE, the Assyrian Empire controlled almost all of Mesopotamia and much of the Levant and Anatolia.[24] Meanwhile, Egypt was weakened, eventually breaking apart after the death of Osorkon II until 710 BCE.[25] In 853, the Assyrians fought and won a battle against a coalition of Babylon, Egypt, Persia, Israel, Aram, and ten other nations, with over 60,000 troops taking part according to contemporary sources.[26] However, the empire was weakened by internal struggles for power, and was plunged into a decade of turmoil beginning with a plague in 763 BCE.[26] Following revolts by cities and lesser kingdoms against the empire, a coup d'état was staged in 745 by Tiglath-Pileser III.[27] He raised the army from 44,000 to 72,000, followed by his successor Sennacherib who raised it to 208,000, and finally by Ashurbanipal who raised an army of over 300,000.[28] This allowed the empire to spread over Cyprus, the entire Levant, Phrygia, Urartu, Cimmerians, Persia, Medes, Elam, and Babylon.[28]

Persian dominance[]

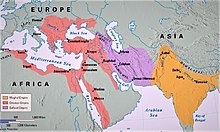

By 650, Assyria had started declining as a severe drought hit the Middle East and an alliance was formed against them.[29] Eventually they were replaced by the Median empire as the main power of the region following the Battle of Carchemish (605) and the Battle of the Eclipse (585).[30] The Medians served as the launching pad for the rise of the Persian Empire.[31] After first serving as vassals, under the third Persian king Cambyses I their influence rose, and in 553 they rose against the Medians.[31] By the death of Cyrus the Great, the Persian Achaemenid Empire reached from Aegean Sea to Indus River and Caucasus to Nubia.[32] The empire was divided into provinces ruled by satraps, who collected taxes and were typically local power brokers.[33] The empire controlled about a third of the world's farm land and a quarter of its population.[34] In 522, after King Cambyses II's death, Darius the Great took over power.[35]

Greek dominance[]

As the population of Ancient Greece grew, they began a colonization of the Mediterranean region.[36] This encouraged trade, which in turn caused political changes in the city-states with old elites being overthrown in Corinth in 657 and in Athens in 632, for example.[37] There were many wars between the cities as well, including the Messenian Wars (743-742; 685-668), the Lelantine War (710-650), and the First Sacred War (595-585).[38] In the seventh and sixth centuries, Corinth and Sparta were the dominant powers of Greece.[39] The former was eventually supplanted by Athens as the main sea power, while Sparta remained the dominant land-force.[40] In 499, in the Ionian Revolt Greek cities in Asia Minor rebelled against the Persian Empire but were crushed in the Battle of Lade.[41] After this, the Persians invaded the Greek mainland in the Greco-Persian Wars (499-449).[42]

The Macedonian King Philip II (350-336) conquered much of Greece.[43] In 338, he formed the League of Corinth to liberate Greeks in Asia Minor from the Persians, with 10,000 troops invading in 336.[44] After his murder, his son Alexander the Great took charge and crossed the Dardanelles in 334.[45] After Asia Minor had been conquered, Alexander invaded Levant, Egypt, and Mesopotamia, defeating the Persians under Darius the Great in the Battle of Gaugamela in 331, and ending the last resistance by 328.[45] After Alexander's death in Babylon in 323, the empire had no designated successor.[46] This led to its division into four: the Antigonid dynasty in Macedonia, the Attalid dynasty in Anatolia, the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Egypt, and the Seleucid Empire over Mesopotamia.[47]

Roman dominance[]

Rome became dominant in the Mediterranean in the 3rd century BC after defeating the Samnites, the Gauls and the Etruscans for control of the Italian Peninsula.[48] In 264, it challenged its main rival Carthage to a fight for Sicily, starting the Punic Wars.[49] A truce was signed in 241, with Rome gaining Corsica and Sardinia in addition to Sicily.[49] In 218, the Carthaginian general Hannibal marched out of Spain towards Italy, crossing the Alps with his war elephants.[50] After 15 years of fighting, the Romans beat him and then sent troops against Carthage itself, defeating it in 202.[51] The Second Punic War alone cost Rome 100,000 casualties.[52] In 146, Carthage was finally destroyed completely.[53]

Rome suffered from various internal disturbances and instabilities. In 133, Tiberius Gracchus was killed alongside hundreds of supporters after trying to redistribute public land to the poor.[54] The Social War (91-88) was caused by neighbouring cities trying to secure themselves the benefits of Roman citizenship.[54] In 82, general Sulla captured power violently, ending the Roman Republic and becoming a dictator.[55] Following his death new power struggles emerged, and in Caesar's Civil War (49-46), Julius Caesar and Pompey fought over the empire, with the former winning.[56] After the ruler was assassinated in 44, a second civil war broke out between his potential heirs, Mark Antony and Augustus, the latter becoming emperor.[56] This then led to the Pax Romana, a long period of peace in the empire.[57] The quarrels between the Ptolemaic Kingdom, the Seleucid Empire, the Parthian Empire and the Kingdom of Pontus in the Near East allowed the Romans to expand up to the Euphrates.[58] During Augustus' reign the Rhine, Danube, and the Sahara became the other borders of the empire.[59] The population reached about 60 million.[60]

Political instability in Rome grew. Emperor Caligula (37-41) was murdered by the Praetorian Guard to replace him with Claudius (41-53), while his successor Nero (54-68) burned Rome down.[61] The average reign from his death to Philip the Arab (244-249) was six years.[61] Nevertheless, external expansion continued, with Trajan (98-117) invading Dacia, Parthia and Arabia.[62] Its only formidable enemy was the Parthian Empire.[63] Migrating peoples started exerting pressure on the borders of the empire.[64] The drying climate of Central Asia forced the Huns to move, and in 370 they crossed Don and soon after the Danube, forcing the Goths on the move, which in turn caused other Germanic tribes to overrun Roman borders.[65] In 293, Diocletian (284-305) appointed three rulers for different parts of the empire.[66] It was formally divided in 395 by Theodosius I (379-395) into the Western Roman and Byzantine Empires.[67] In 406 the northern border of the former was overrun by the Alemanni, Vandals and Suebi invaded.[68] In 408 the Visigoths invaded Italy and then sacked Rome in 410.[68] The final collapse of the Western Empire came in 476 with the deposal of Romulus Augustulus (475-476).[69]

Indian subcontinent[]

Built around the Indus River, by 2500 BCE the Indus Valley Civilization, located in modern-day India, Pakistan and Afghanistan, had formed. The civilization's boundaries extended to 600 km from the Arabian Sea.[70] After its cities Mohenjo-daro and Harappa were abandoned around 1900 BCE, no political power replaced it.[71]

States began to form in the 6th century BCE with the Mahajanapadas.[72] Out of sixteen such states, four strong ones emerged: Kosala, Magadha, Vatsa, and Avanti, with Magadha dominating the rest by the mid-fifth century.[73] The Magadha then transformed into the Nanda Empire under Mahapadma Nanda (345-321), extending from the Gangetic plains to the Hindu Kush and the Deccan Plateau.[74] The empire was, however, overtaken by Chandragupta Maurya (324-298), turning it into the Maurya Empire.[74] He defended against Alexander's invasion from the West and received control of the Hindu Kush mountain passes in a peace treaty signed in 303.[74] By the time of his grandson Ashoka's rule, the empire stretched from Zagros Mountains to the Brahmaputra River.[75] The empire contained a population of 50 to 60 million, governed by a system of provinces ruled by governor-princes, with a capital in Pataliputra.[76]

After Ashoka's death, the empire had begun to decline, with Kashmir in the north, Shunga and Satavahana in the centre, and Kalinga as well as Pandya in the south becoming independent.[77] In to this power vacuum, the Yuezhi were able to establish the new Kushan Empire in 30 CE.[78] The Gupta Empire was founded by Chandragupta I (320-335), which in sixty years expanded from the Ganges to the Bay of Bengal and the Indus River following the downfall of the Kushan Empire.[79] Gupta governance was similar to that of the Maurya.[80] Following wars with the Hephthalites and other problems, the empire fell by 550.[81]

China[]

In the North China Plain, the Yellow River allowed the rise of states such as Wei and Qi.[82] This area was first unified by the Shang dynasty around 1600 BCE, and replaced by the Zhou dynasty in the Battle of Muye in 1046 BCE, with reportedly millions taking part in the fighting.[82] The victors were however hit by internal unrest soon after.[83] The main rivals of the Zhou were the Dongyi in Shandong, the Xianyun in Ordos, the Guifang in Shanxi, as well as the Chu in the middle reaches of the Yangtze.[84]

Beginning in the eighth century BCE China fell into a state of anarchy for five centuries during the Spring and Autumn (771-476) and Warring States periods (476-221).[85] During the latter period, the Jin dynasty split into the Wei, Zhao and Han states, while the rest of the North China Plain was composed of the Chu, Qin, Qi and Yan states, while the Zhou remained in the centre with largely ceremonial power.[86] While the Zhao had an advantage at first, the Qin ended up defeating them in 260 with about half a million soldiers fighting on each side at the Battle of Changping.[87] The other states tried to form an alliance against the Qin but were defeated.[88] In 221, the Qin dynasty was established with a population of about 40 million, with a capital of 350,000 in Linzi.[89] Under the leadership of Qin Shi Huang, the dynasty initiated reforms such as establishing territorial administrative units, infrastructure projects (including the Great Wall of China) and uniform Chinese characters.[90] However, after his death and burial with the Terracotta Army, the empire started falling apart when the Chu and Han started fighting over a power vacuum left by a weak heir, with the Han dynasty rising to power in 204 BCE.[91]

Under the Han, the population of China rose to 50 million, with 400,000 in the capital Chang'an, and with territorial expansion to Korea, Vietnam and Tien Shan.[92] Expeditions were also sent against the Xiongnu and to secure the Hexi Corridor, the Nanyue kingdom was annexed, and Hainan and Taiwan conquered.[93] The Chinese pressure on the Xiongnu forced them towards the west, leading to the exodus of the Yuezhi, who in turn pillaged the capital of Bactria.[94] This then led to their new Kushan Empire.[78] The end of the Han dynasty came following internal upheavals in 220 CE, with its split into the Shu, Wu and Wei states.[95] Despite the rise of the Jin dynasty (266–420), China was soon invaded by the Xiongnu in the rebellion of the Five Barbarians (304-316), who conquered large areas of the Northern China plain and declared the Northern Wei in 399.[96]

Americas[]

The Olmecs were the first major Indigenous American culture, with some smaller ones such as the Chavín culture amongst mainly hunter-gatherers.[97] The Olmecs were limited by the dense forests and the long rainy season, as well as the lack of horses.[98]

Post-classical era[]

Africa[]

The eastern coast of Africa contained a string of trading cities connected to kingdoms in the interior.[99] The Horn of Africa was dominated by the Ethiopian Empire by the 13th and 14th centuries.[99] South from it were the Swahili cities of Mogadishu, Mombasa, Zanzibar, Kilwa, and Sofala.[100] By the 14th century, Kilwa had conquered most of the others.[100] It also engaged in campaigns against the inland power of Great Zimbabwe.[100] Great Zimbabwe was itself overtake in trade by its rival, the Kingdom of Mutapa.[100] Towards the north, the Empire of Kitara dominated the Great Lakes in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.[101] Towards the Atlantic coast, the Kingdom of Kongo was of regional importance around the same time.[101] The Gulf of Guinea had the Kingdom of Benin.[101] To the north, in the Sahel, there was a tripartite competition between the Mossi Kingdoms, the Songhai Empire, as well as the Mali Empire, with the latter declining in the fifteenth century.[102]

Americas[]

The Tiwanaku Polity polity in western Bolivia based in the southern Lake Titicaca Basin. Its influence extended into present-day Peru and Chile and lasted from around 600 to 1000 AD.[103] Chimor was the political grouping of the Chimú culture that ruled the northern coast of Peru beginning around 850 and ending around 1470. Chimor was the largest kingdom in the Late Intermediate period, encompassing 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) of coastline. The Aymara kingdoms in turn were a group of native polities that flourished towards the Late Intermediate Period, after the fall of the Tiwanaku Empire, whose societies were geographically located in the Qullaw. They were developed between 1150 and 1477, before the kingdoms disappeared due to the military conquest of the Inca Empire.

Beginning around 250 AD, the Maya civilization develop many city-states linked by a complex trade network. In the Maya Lowlands two great rivals, the cities of Tikal and Calakmul, became powerful. The period also saw the intrusive intervention of the central Mexican city of Teotihuacan in Maya dynastic politics. In the 9th century, there was a widespread political collapse in the central Maya region, resulting in internecine warfare, the abandonment of cities, and a northward shift of population. The Postclassic period saw the rise of Chichen Itza in the north, and the expansion of the aggressive Kʼicheʼ kingdom in the Guatemalan Highlands. In the 16th century, the Spanish Empire colonised the Mesoamerican region, and a lengthy series of campaigns saw the fall of Nojpetén, the last Maya city, in 1697.

The Aztec Empire was formed as an alliance of three Nahua altepetl city-states: Mexico-Tenochtitlan, Tetzcoco, and Tlacopan. from the victorious factions of a civil war fought between the city of Azcapotzalco and its former tributary provinces. These three city-states ruled the area in and around the Valley of Mexico from 1428 until the combined forces of the Spanish conquistadores and their native allies under Hernán Cortés defeated them in 1521. Despite the initial conception of the empire as an alliance of three self-governed city-states, Tenochtitlan quickly became dominant militarily.[104] By the time the Spanish arrived in 1519, the lands of the Alliance were effectively ruled from Tenochtitlan, while the other partners in the alliance had taken subsidiary roles. The Tarascan state was the second-largest state in Mesoamerica at the time.[105]It was founded in the early 14th century.

Asia[]

When China entered the Sui Dynasty,[106] the government changed and expanded in its borders as the many separate bureaucracies unified under one banner.[107] This evolved into the Tang Dynasty when Li Yuan took control of China in 626.[108] By now, the Chinese borders had expanded from eastern China, up north into the Tang Empire.[109] The Tang Empire fell apart in 907 and split into ten regional kingdoms and five dynasties with vague borders.[110] Fifty-three years after the separation of the Tang Empire, China entered the Song Dynasty under the rule of Chao K'uang, although the borders of this country expanded, they were never as large as those of the Tang dynasty and were constantly being redefined due to attacks from the neighboring Tartar (Mongol) people known as the Khitan tribes.[111]

The Mongol Empire emerged from the unification of several nomadic tribes in the Mongol homeland under the leadership of Genghis Khan (c. 1162–1227), whom a council proclaimed as the ruler of all Mongols in 1206. The empire grew rapidly under his rule and that of his descendants, who sent out invading armies in every direction.[112][113] The vast transcontinental empire connected the East with the West, the Pacific to the Mediterranean, in an enforced Pax Mongolica, allowing the dissemination and exchange of trade, technologies, commodities and ideologies across Eurasia.[114][115] The Mongol invasion halted China's economic development for over 150 years, decisively changing the balance of power in the Eastern Hemisphere.[116]

The empire began to split due to wars over succession, as the grandchildren of Genghis Khan disputed whether the royal line should follow from his son and initial heir Ögedei or from one of his other sons, such as Tolui, Chagatai, or Jochi. The Toluids prevailed after a bloody purge of Ögedeid and Chagataid factions, but disputes continued among the descendants of Tolui. After Möngke Khan died (1259), rival kurultai councils simultaneously elected different successors, the brothers Ariq Böke and Kublai Khan, who fought each other in the Toluid Civil War (1260–1264) and also dealt with challenges from the descendants of other sons of Genghis.[117][118] Kublai successfully took power, but civil war ensued as he sought unsuccessfully to regain control of the Chagatayid and Ögedeid families. By the time of Kublai's death in 1294 the Mongol Empire had fractured into four separate khanates or empires, each pursuing its own separate interests and objectives: the Golden Horde khanate in the northwest, the Chagatai Khanate in Central Asia, the Ilkhanate in the southwest, and the Yuan dynasty in the east, based in modern-day Beijing.[119]

In 1304 the three western khanates briefly accepted the nominal suzerainty of the Yuan dynasty,[120][121] but in 1368 the Han Chinese Ming dynasty took over the Mongol capital. The Genghisid rulers of the Yuan retreated to the Mongolian homeland and continued to rule there as the Northern Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty the largest army in the world with almost a million soldiers.[122] It was therefore able to conduct military campaigns in Manchuria, Inner Mongolia, Yunnan, and Vietnam.[123] Naval voyages were also sent, with the Ming treasure voyages reaching Africa.[123] These also intervened militarily in Java, Sumatra, and Sri Lanka.[124] The Ilkhanate disintegrated in the period 1335–1353. The Golden Horde had broken into competing khanates by the end of the 15th century and was defeated and thrown out of Russia in 1480 by the Grand Duchy of Moscow while the Chagatai Khanate lasted in one form or another until 1687.

Middle East and Europe[]

The Byzantine–Sasanian Wars of 572–591 and 602–628 produced the cumulative effects of a century of almost continuous conflict, leaving both empires crippled. When Kavadh II died only months after coming to the throne, Persia was plunged into several years of dynastic turmoil and civil war. The Sasanians were further weakened by economic decline, heavy taxation from Khosrau II's campaigns, religious unrest, and the increasing power of the provincial landholders.[125] The Byzantine Empire was also severely affected, with its financial reserves exhausted by the war and the Balkans now largely in the hands of the Slavs.[126] Additionally, Anatolia was devastated by repeated Persian invasions; the Empire's hold on its recently regained territories in the Caucasus, Syria, Mesopotamia, Palestine and Egypt was loosened by many years of Persian occupation.[127] Neither empire was given any chance to recover, and according to George Liska, the "unnecessarily prolonged Byzantine–Persian conflict opened the way for Islam".[128]

The Quraysh ruled the cities of Mecca and Medina, and expelled their member Muhammad from the former to the latter in 622, from where he began spreading his new religion, Islam.[129] In 631 Muhammad marched with 10,000 to Mecca and conquered it before dying the next year.[130] His successors united most of Arabia in the Ridda wars (632-633) and then started the Muslim conquests of the Levant (634-641), Egypt (639-642) and Persia (633-651), the latter ending the Sasanian empire.[131] In less than a decade after his death, the Islamic Rashidun Caliphate extended its reach from Atlas Mountains in the west to the Hindu Kush in the east.[132] However, the First Fitna led to its replacement by the Umayyad Caliphate in 661, moving the centre of power to Damascus.[133] At its height, the Umayaads ruled a third of the world's population.[134] In 750, the Abbasid Caliphate replaced the Umayyads in the Abbasid Revolution.[135] In 762, they moved the capital to Baghdad.[136] The Emirate of Córdoba remained under Umayaad rule, while in 788 the Idrisid dynasty broke away in Morocco.[137] The Fatimid Caliphate started taking over North Africa from 909 onwards, and the Buyid dynasty broke away in Persia and later Mesopotamia starting in the 930's.[138]

In 711, the Umayyad conquest of Hispania began, and in 717 they crossed the Pyrenees into the European Plain.[139] They were met by the Merovingian dynasty, which had been established by Clovis I (481-511), which was in decline, leading Charles Martel to seize power and defeat the invasion force at the Battle of Tours in 732.[139] His son Pepin the Short established the Carolingian dynasty in 751.[139] Charlemagne (768-814) turned it into the Carolingian Empire, being crowned Emperor of the Romans in 800 by the Pope, with this forming the basis for the later Holy Roman Empire.[140] Meanwhile, in Eastern Europe, Krum (795-814) expanded the Bulgarian Empire.[141] The Treaty of Verdun divided Carolingian Empire into West, Middle and East Francia.[142]

During the Viking Age (793–1066 AD), Norsemen known as Vikings undertook large-scale raiding, colonizing, conquest, and trading throughout Europe, and reached North America.[143][144] Voyaging by sea from their homelands in Denmark, Norway and Sweden, the Norse people settled in the British Isles, Ireland, the Faroe Islands, Iceland, Greenland, Normandy, the Baltic coast, and along the Dnieper and Volga trade routes in eastern Europe, where they were also known as Varangians. They also briefly settled in Newfoundland, becoming the first Europeans to reach North America. The Vikings founded several kingdoms and earldoms in Europe: the kingdom of the Isles (Suðreyjar), Orkney (Norðreyjar), York (Jórvík) and the Danelaw (Danalǫg), Dublin (Dyflin), Normandy, and Kievan Rus' (Garðaríki). The Norse homelands were also unified into larger kingdoms during the Viking Age, and the short-lived North Sea Empire included large swathes of Scandinavia and Britain.

In 1095, Pope Urban II proclaimed the First Crusade at the Council of Clermont. He encouraged military support for Byzantine Emperor Alexios I against the Seljuk Turks and an armed pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Across all social strata in western Europe there was an enthusiastic popular response. Volunteers took a public vow to join the crusade. Historians now debate the combination of their motivations, which included the prospect of mass ascension into Heaven at Jerusalem, satisfying feudal obligations, opportunities for renown, and economic and political advantage. Initial successes established four Crusader states in the Near East: the County of Edessa; the Principality of Antioch; the Kingdom of Jerusalem; and the County of Tripoli. The crusader presence remained in the region in some form until the city of Acre fell in 1291, leading to the rapid loss of all remaining territory in the Levant. After this, there were no further crusades to recover the Holy Land.

Following the end of the Carolingian Empire, the largest polities in Western Europe were the Holy Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire, Kingdom of France, and the Kingdom of England.[145] The Catholic Church also wielded tremendous power.[145] In Eastern Europe, the Mongol invasion of Europe killed half the population 1237 to 1241.[146] The resulting power vacuum helped the Teutonic Order, while the Kingdom of Poland and the Kingdom of Hungary became the main Catholic realms.[147] Further east, the Kievan Rus' continued to prosper.[147] The main power to the south meanwhile was the Byzantine Empire.[147] However, by 1180, the Republic of Venice had changed the balance of maritime power in the Mediterranean.[148] In the Greater Middle East, power was divided between the Seljuk Empire, the Fatimid Caliphate, the Buyid dynasty, and the Ghaznavids.[149] No Islamic power was able to hold Egypt, the Levant, Mesopotamia, and Persia at the same time again.[150] In 1258, the Mongol Siege of Baghdad pushed the Islamic world into disarray.[151]

The Seljuk dynasty was founded by Osman I (1200-1323), leading to the Ottoman Empire.[152] In 1345, the Ottomans entered Europe across the Dardanelles, conquering Thessaloniki in 1387, and advancing to Kosovo by 1389.[153] The Fall of Constantinople followed in 1453.[153] The Fall of Constantinople marked the end of the Byzantine Empire, and effectively the end of the Roman Empire, a state which dated back to 27 BC and lasted nearly 1,500 years. The conquest of Constantinople and the fall of the Byzantine Empire was a key event of the Late Middle Ages and is considered the end of the Medieval period.

India[]

Indian politics revolved around the struggle between the Buddhist Pala Empire, the Hindu Gurjara-Pratihara dynasty, the Jainist Rashtrakuta dynasty, as well as the Islamic caliphate.[154] The Pala Empire had risen around 750 in Bengal under Gopala I, while the Rashtrakutas had emerged around the same time in the Deccan Plateau and the southern coast under Dantidurga.[155] The Pratiharas first united the Indo-Gangetic Plain under Nagabhata I (c. 730-760), who has defeated an Islamic invasion of northern India.[155] The struggle between the four lasted for almost 200 years.[156] By the ninth century, the Ghaznavids, a breakaway from the caliphate, arose after taking advantage of the others' internal weaknesses.[157]

The Chola dynasty arose as the one of Asia's strongest trading powers before invading Sri Lanka at the end of the 900's.[158] In 1025, they attacked rival commercial kingdom of Srivijaya in Southeast Asia.[158] Their enemies in India included an alliance of Pandyan princes and the Chalukya dynasty.[158] However, the Ghurid dynasty invaded the northern parts of the subcontinent 1175 to 1186, conquering much of them.[159][160] In 1206, Qutb al-Din Aibak founded the Delhi Sultanate.[160] By the 14th century, it controlled the Indo-Gangetic Plain and the Deccan Plateau.[160] In the middle of the century, the latter saw the rise of the Vijayanagara Empire, which ruled much of southern India as a federation.[161] The Sultanate and the Empire engaged in continuous warfare without either being able to defeat the other.[161]

Early modern era[]

Americas[]

Beginning with the 1492 arrival of Christopher Columbus in the Caribbean and gaining control over more territory for over three centuries, the Spanish Empire would expand across the Caribbean Islands, half of South America, most of Central America and much of North America. The major empires of the American continents were defeated by much smaller Spanish forces. The Aztec Empire empire under Moctezuma II had 200,000 troops under its command, but was defeated by little over 600 conquistadors.[162] The Inca Empire under Atahualpa with 60,000 soldiers was defeated by 168 Spaniards, meanwhile.[162] In both cases, the Spanish used deception to capture the heads of state.[162]

Following an earlier expedition to Yucatán led by Juan de Grijalva in 1518, Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés led an expedition (entrada) to Mexico. Two years later, in 1519, Cortés and his retinue set sail for Mexico.[163] Cortés made alliances with tributary city-states (altepetl) of the Aztec Empire as well as their political rivals, particularly the Tlaxcaltecs and Tetzcocans, a former partner in the Aztec Triple Alliance. Other city-states also joined, including Cempoala and Huejotzingo and polities bordering Lake Texcoco, the inland lake system of the Valley of Mexico. The Spanish campaign against the Aztec Empire had its final victory on 13 August 1521, when a coalition army of Spanish forces and native Tlaxcalan warriors led by Cortés and Xicotencatl the Younger captured the emperor Cuauhtémoc and Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Aztec Empire. The fall of Tenochtitlan marks the beginning of Spanish rule in central Mexico, and they established their capital of Mexico City on the ruins of Tenochtitlan.

After years of preliminary exploration and military skirmishes, 168 Spanish soldiers under conquistador Francisco Pizarro, his brothers, and their indigenous allies captured the Sapa Inca Atahualpa in the 1532 Battle of Cajamarca. It was the first step in a long campaign that took decades of fighting but ended in Spanish victory in 1572 and colonization of the region as the Viceroyalty of Peru.

The Spanish conquest of the Muisca took place from 1537 to 1540. Meanwhile, the Calchaquí Wars were a series of military conflicts between the Diaguita Confederation and the Spanish Empire in the 1560–1667 period. After many initial Spanish successes in the Arauco War against the Mapuche, the Battle of Curalaba in 1598 and the following destruction of the Seven Cities marked a turning point in the war leading to the establishment of a clear frontier between the Spanish domains and the land of the independent Mapuche.

Asia[]

Gunpowder Empires[]

The Gunpowder Empires were the Ottoman, Safavid and Mughal empires as they flourished from the 16th century to the 18th century. These three empires were among the strongest and most stable economies of the early modern period, leading to commercial expansion, and greater patronage of culture, while their political and legal institutions were consolidated with an increasing degree of centralisation. The empires underwent a significant increase in per capita income and population, and a sustained pace of technological innovation. They stretched from Central Europe and North Africa in the west to between today's modern Bangladesh and Myanmar in the east.

Under Sultan Selim I (1512-1520), the Ottomans defeated the Safavids in the Battle of Chaldiran (1514).[164] His successor, Suleiman the Magnificent (1520-1566), the Ottoman Empire marked the peak of its power and prosperity as well as the highest development of its government, social, and economic systems.[165] Already controlling the Balkans, it was able to invade Hungary and win in the Battle of Mohács (1526).[166] However, further advancement failed after the Siege of Vienna (1529).[167] Following naval victories in the Battle of Preveza (1538) and the Battle of Djerba (1560), the Ottomans also emerged as the dominant maritime power in the Mediterranean.[168] A sailing voyage even reached the Aceh Sultanate in 1565.[169] At the beginning of the 17th century, the empire contained 32 provinces and numerous vassal states. Some of these were later absorbed into the Ottoman Empire, while others were granted various types of autonomy over the course of centuries.[note 1]

However, the Ottomans began to face many challenges. The failure to conquer the Safavid Empire forced it to keep forces in the east, while the expansion of the Russian Empire put pressure on the Black Sea territories.[169] Meanwhile, Western powers began to overtake their maritime capabilities, with the Battle of Lepanto (1571) being a turning point.[169] In 1683, the Battle of Vienna halted an Ottoman invasion again, with the Christian Holy League driving the Empire back into the Balkans.[169] Despite the Venetian reconquest of Morea (Peloponnese) in the 1680s and it was recovered in 1715, while the island of Corfu under Venetian rule remained the only Greek island not conquered by the Ottomans. The Ottoman Empire still remained the largest power in the Mediterranean and the Middle East.[170]

The Safavid dynasty ruled Persia from 1501 to 1722 (experiencing a brief restoration from 1729 to 1736). It ruled from the Black Sea to the Hindu Kush, with more than 50 million inhabitants.[170] Originating from Caucasian warriors called the Qizilbash, they conquered Armenia in 1501, most of Persia by 1504, parts of Uzbekistan in 1511, and unsuccessfully fighting over Caucasus and Mesopotamia until 1555.[171] However, Baghdad was recaptured in 1623.[171] The expansion of Russia in the north eventually started to pose a threat.[172] The Empire was finally defeated by and divided between the Ottomans and the Russians in 1722-23.[173]

The Mughal Empire, was an empire in South Asia.[174] For some two centuries, the empire stretched from the outer fringes of the Indus basin in the west, northern Afghanistan in the northwest, and Kashmir in the north, to the highlands of present-day Assam and Bangladesh in the east, and the uplands of the Deccan plateau in south India.[175] In 1505, Central Asian invaders had entered the Indo-Gangetic Plain and established the Empire under Akbar (1556-1605).[173] The neglect of northern defences allowed the Persians under Nader Shah to invade in 1739, with the capital Delhi sacked.[176]

East Asia[]

Under the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), China's population and economy grew.[177] While the Portuguese were at first successfully kept out, Japanese pirates began to attack the coast, forcing co-operation with the Portugues who established a trading settlement at Macau in 1554.[178] Northern Mongol and Jurchen people established a coalition to invade the country, reaching Beijing in 1550.[178] In 1592, the Japanese invaded Korea, while rebellions emerged in China.[179]

Europe[]

In 1700, Charles II of Spain died, naming Phillip of Anjou, Louis XIV's grandson, his heir. Charles' decision was not well met by the British, who believed that Louis would use the opportunity to ally France and Spain and attempt to take over Europe. Britain formed the Grand Alliance with Holland, Austria and a majority of the German states and declared war against Spain in 1702. The War of the Spanish Succession lasted 11 years, and ended when the Treaty of Utrecht was signed in 1714.[180]

Less than 50 years later, in 1740, war broke out again, sparked by the invasion of Silesia, part of Austria, by King Frederick II of Prussia. Britain, the Netherlands and Hungary supported Maria Theresa. Over the next eight years, these and other states participated in the War of the Austrian Succession, until a treaty was signed, allowing Prussia to keep Silesia.[181][182] The Seven Years' War began when Theresa dissolved her alliance with Britain and allied with France and Russia. In 1763, Britain won the war, claiming Canada and land east of the Mississippi. Prussia also kept Silesia.[183]

Oceania[]

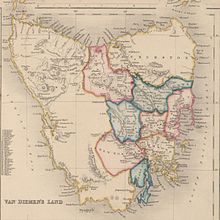

Interest in the geography of the Southern Hemisphere began to increase in the 18th century.[184] In 1642, Dutch navigator Abel Tasman was commissioned to explore the Southern Hemisphere; during his voyages, Tasman discovered the island of Van Diemen's Land, which was later named Tasmania, the Australian coast, and New Zealand in 1644.[185] Captain James Cook was commissioned in 1768 to observe a solar eclipse in Tahiti and sailed into Stingray Harbor on Australia's east coast in 1770, claiming the land for the British Crown.[186] Settlements in Australia began in 1788 when Britain began to utilize the country for the deportation of convicts,[187] with the first free settles arriving in 1793.[188] Likewise New Zealand became a home for hunters seeking whales and seals in the 1790s with later non-commercial settlements by the Scottish in the 1820s and 30s.[189]

Modern era[]

Revolutionary waves[]

The Atlantic Revolutions were a revolutionary wave in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. It took place in both the Americas and Europe, including the Corsican Revolution (1755–1769), American Revolution (1765–1783), Geneva Revolution of 1782, Revolt of Dutch Patriots (1785), Polish–Russian War of 1792 (1788–1792), French Revolution and its aftermath (1789–1814), Liège Revolution (1789–1795), Brabant Revolution (1790), Haitian Revolution (1791–1804), Batavian Revolution (1795), Slave revolt in Curaçao (1795), Fédon's rebellion (1796), Scottish Rebellion (1797), Irish Rebellion (1798), Helvetic Revolution (1798), and Altamuran Revolution (1799), 1811 German Coast uprising (1811), and the Norwegian War of Independence (1814). There were smaller upheavals in Switzerland, Russia, and Brazil. The revolutionaries in each country knew of the others and to some degree were inspired by or emulated them.[190]

The French Revolutionary Wars were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted France against Great Britain, the Holy Roman Empire, Prussia, Russia, and several other monarchies. They are divided in two periods: the War of the First Coalition (1792–97) and the War of the Second Coalition (1798–1802). Initially confined to Europe, the fighting gradually assumed a global dimension. After a decade of constant warfare and aggressive diplomacy, France had conquered territories in the Italian Peninsula, the Low Countries and the Rhineland in Europe and was retroceded Louisiana in North America. French success in these conflicts ensured the spread of revolutionary principles over much of Europe.

The Coup of 18 Brumaire brought General Napoleon Bonaparte to power as First Consul of France and in the view of most historians ended the French Revolution. The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European powers formed into various coalitions. It produced a brief period of French domination over most of continental Europe. The wars stemmed from the unresolved disputes associated with the French Revolution and its resultant conflict. The wars are often categorised into five conflicts, each termed after the coalition that fought Napoleon: the Third Coalition (1805), the Fourth (1806–07), the Fifth (1809), the Sixth (1813–14), and the Seventh (1815).

The Peninsular War with France, which resulted from the Napoleonic occupation of Spain, caused Spanish Creoles in Spanish America to question their allegiance to Spain, stoking independence movements that culminated in various Spanish American wars of independence (1808–33), which were primarily fought between opposing groups of colonists and only secondarily against Spanish forces. At the same time, the Portuguese monarchy relocated to Brazil during Portugal's French occupation. After the royal court returned to Lisbon, the prince regent, Pedro, remained in Brazil and in 1822 successfully declared himself emperor of a newly independent Brazilian Empire.

Revolutions during the 1820s included the Carbonari in Italy, the Trienio Liberal in Spain, the Liberal Revolution of 1820 in the Kingdom of Portugal, the Greek War of Independence, and the Decembrist revolt in the Russian Empire. Followed by these, the Revolutions of 1830 were a included the Belgian Revolution in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, the July Revolution in France, the November Uprising in the Congress Poland, and the Ustertag in Switzerland. The Revolutions of 1848 in turn were the most widespread revolutionary wave in European history. They included the March Revolution, French Revolution, German revolutions, the Revolutions in the Italian states, Greater Poland uprising, March Unrest, Revolutions in the Austrian Empire, Praieira revolt, Revolution in Luxembourg, Moldavian Revolution, Wallachian Revolution, Chartism, and the Young Ireland rebellion.

Great power competition[]

Inspired by the rebellions in the 1820s and 1830s against the outcome of the Congress of Vienna, the Italian unification process was precipitated by the revolutions of 1848, and reached completion in 1871, when Rome was officially designated the capital of the Kingdom of Italy.[191][192] After the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, Prussia, under Otto von Bismarck, brought together almost all the German states (excluding Austria, Luxembourg and Liechtenstein) into a new German Empire. Bismarck's new empire became the most powerful state in continental Europe until 1914.[193][194] Meanwhile, Britain had entered an era of "splendid isolation", avoiding entanglements that had led it into the Crimean War in 1854–1856. It concentrated on internal industrial development and political reform, and building up its great international holdings, the British Empire, while maintaining by far the world's strongest Navy to protect its island home and its many overseas possessions.

World war I[]

World War I saw the continent of Europe split into two major opposing alliances; the Allied Powers, primarily composed of the United Kingdom of Great Britain & Ireland, the United States, France, the Russian Empire, Italy, Japan, Portugal, and the many aforementioned Balkan States such as Serbia and Montenegro; and the Central Powers, primarily composed of the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria. Though Serbia was defeated in 1915, and Romania joined the Allied Powers in 1916, only to be defeated in 1917, none of the great powers were knocked out of the war until 1918. The 1917 February Revolution in Russia replaced the Monarchy with the Provisional Government, but continuing discontent with the cost of the war led to the October Revolution, the creation of the Soviet Socialist Republic, and the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk by the new government in March 1918, ending Russia's involvement in the war. One by one, the Central Powers quit: first Bulgaria (September 29), then the Ottoman Empire (October 31) and the Austro-Hungarian Empire (November 3). With its allies defeated, revolution at home, and the military no longer willing to fight, Kaiser Wilhelm abdicated on 9 November and Germany signed an armistice on 11 November 1918, ending the war.

The partitioning of the Ottoman Empire after the war led to the domination of the Middle East by Western powers such as Britain and France, and saw the creation of the modern Arab world and the Republic of Turkey. The League of Nations mandate granted the French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon, the British Mandate for Mesopotamia (later Iraq) and the British Mandate for Palestine, later divided into Mandatory Palestine and the Emirate of Transjordan (1921–1946). The Ottoman Empire's possessions in the Arabian Peninsula became the Kingdom of Hejaz, which the Sultanate of Nejd (today Saudi Arabia) was allowed to annex, and the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen. The Empire's possessions on the western shores of the Persian Gulf were variously annexed by Saudi Arabia (al-Ahsa and Qatif), or remained British protectorates (Kuwait, Bahrain, and Qatar) and became the Arab States of the Persian Gulf.

The Revolutions of 1917–1923 included political unrest and revolts around the world inspired by the success of the Russian Revolution and the disorder created by the aftermath of World War I. In war-torn Imperial Russia, the liberal February Revolution toppled the monarchy. A period of instability followed, and the Bolsheviks seized power during the October Revolution. In response to the emerging Soviet Union, anticommunist forces from a broad assortment of ideological factions fought against the Bolsheviks, particularly by the counter-revolutionary White movement and the peasant Green armies, the various nationalist movements in Ukraine after the Russian Revolution and other would-be new states like those in Soviet Transcaucasia and Soviet Central Asia, the anarchist-inspired Third Russian Revolution and the Tambov Rebellion.[195] The Leninist victories also inspired a surge by world communism: the larger German Revolution and its offspring, like the Bavarian Soviet Republic, the neighbouring Hungarian Revolution, and the Biennio Rosso in Italy, in addition to various smaller uprisings, protests and strikes, all of which proved abortive. The Bolsheviks sought to coordinate this new wave of revolution in the Soviet-led Comintern.

The rise of fascism[]

The conditions of economic hardship caused by the Great Depression brought about an international surge of social unrest. In Germany, it contributed to the rise of the National Socialist German Workers' Party, which resulted in the demise of the Weimar Republic and the establishment of the fascist regime, Nazi Germany, under the leadership of Adolf Hitler. Fascist movements grew in strength elsewhere in Europe. Hungarian fascist Gyula Gömbös rose to power as Prime Minister of Hungary in 1932 and attempted to entrench his Party of National Unity throughout the country. The fascist Iron Guard movement in Romania soared in political support after 1933, gaining representation in the Romanian government, and an Iron Guard member assassinated Romanian prime minister Ion Duca. During the 6 February 1934 crisis, France faced the greatest domestic political turmoil since the Dreyfus Affair when the fascist Francist Movement and multiple far-right movements rioted en masse in Paris against the French government resulting in major political violence.

In the Americas, the Brazilian Integralists led by Plínio Salgado claimed as many as 200,000 members although following coup attempts it faced a crackdown from the Estado Novo of Getúlio Vargas in 1937. In the 1930s, the National Socialist Movement of Chile gained seats in Chile's parliament and attempted a coup d'état that resulted in the Seguro Obrero massacre of 1938.

World War II[]

World War II is generally considered to have begun on 1 September 1939, when Nazi Germany, under Adolf Hitler, invaded Poland. The United Kingdom and France subsequently declared war on Germany on the 3rd. Under the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact of August 1939, Germany and the Soviet Union had partitioned Poland and marked out their "spheres of influence" across Finland, Romania and the Baltic states. From late 1939 to early 1941, in a series of campaigns and treaties, Germany conquered or controlled much of continental Europe, and formed the Axis alliance with Italy and Japan (along with other countries later on). Following the onset of campaigns in North Africa and East Africa, and the fall of France in mid-1940, the war continued primarily between the European Axis powers and the British Empire, with war in the Balkans, the aerial Battle of Britain, the Blitz of the UK, and the Battle of the Atlantic. On 22 June 1941, Germany led the European Axis powers in an invasion of the Soviet Union, opening the Eastern Front, the largest land theatre of war in history and trapping the Axis powers, crucially the German Wehrmacht, in a war of attrition.

Japan, which aimed to dominate Asia and the Pacific, was at war with the Republic of China by 1937. In December 1941, Japan attacked American and British territories with near-simultaneous offensives against Southeast Asia and the Central Pacific, including an attack on the US fleet at Pearl Harbor which forced the US to declare war against Japan; the European Axis powers declared war on the US in solidarity. Japan soon captured much of the western Pacific, but its advances were halted in 1942 after losing the critical Battle of Midway; later, Germany and Italy were defeated in North Africa and at Stalingrad in the Soviet Union. Key setbacks in 1943—including a series of German defeats on the Eastern Front, the Allied invasions of Sicily and the Italian mainland, and Allied offensives in the Pacific—cost the Axis powers their initiative and forced it into strategic retreat on all fronts. In 1944, the Western Allies invaded German-occupied France, while the Soviet Union regained its territorial losses and turned towards Germany and its allies. During 1944 and 1945, Japan suffered reversals in mainland Asia, while the Allies crippled the Japanese Navy and captured key western Pacific islands.

The war in Europe concluded with the liberation of German-occupied territories, and the invasion of Germany by the Western Allies and the Soviet Union, culminating in the fall of Berlin to Soviet troops, Hitler's suicide and the German unconditional surrender on 8 May 1945. Following the Potsdam Declaration by the Allies on 26 July 1945 and the refusal of Japan to surrender on its terms, the United States dropped the first atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima, on 6 August, and Nagasaki, on 9 August. Faced with an imminent invasion of the Japanese archipelago, the possibility of additional atomic bombings, and the Soviet entry into the war against Japan and its invasion of Manchuria, Japan announced its intention to surrender on 15 August, then signed the surrender document on 2 September 1945, cementing total victory in Asia for the Allies.

World War II changed the political alignment and social structure of the globe. The United Nations (UN) was established to foster international co-operation and prevent future conflicts, and the victorious great powers—China, France, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States—became the permanent members of its Security Council. The Soviet Union and the United States emerged as rival superpowers, setting the stage for the nearly half-century-long Cold War. In the wake of European devastation, the influence of its great powers waned, triggering the decolonisation of Africa and Asia. Most countries whose industries had been damaged moved towards economic recovery and expansion. Political integration, especially in Europe, began as an effort to forestall future hostilities, end pre-war enmities and forge a sense of common identity.

Notes[]

- ^ The empire also temporarily gained authority over distant overseas lands through declarations of allegiance to the Ottoman Sultan and Caliph, such as the declaration by the Sultan of Aceh in 1565, or through temporary acquisitions of islands such as Lanzarote in the Atlantic Ocean in 1585, Turkish Navy Official Website: "Atlantik'te Türk Denizciliği"

References[]

- ^ Fukuyama, Francis (2012-03-27). The Origins of Political Order: From Prehuman Times to the French Revolution. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-374-53322-9.

- ^ Fukuyama, Francis. (2012). The origins of political order : from prehuman times to the French Revolution (Kindle ed.). Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-374-53322-9. OCLC 1082411117.

- ^ Fukuyama, Francis. (2012). The origins of political order : from prehuman times to the French Revolution (Kindle ed.). Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-374-53322-9. OCLC 1082411117.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan, author., A political history of the world : three thousand years of war and peace, p. 26, ISBN 978-0-241-38466-4, OCLC 1080190517CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan, author., A political history of the world : three thousand years of war and peace, ISBN 978-0-241-38466-4, OCLC 1080190517CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Holslag, Jonathan, author., A political history of the world : three thousand years of war and peace, pp. 24–25, ISBN 978-0-241-38466-4, OCLC 1080190517CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Dartnell, Lewis (2019-01-31). Origins: How the Earth Shaped Human History. Random House. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-4735-4733-9.

- ^ Dartnell, Lewis (2019-01-31). Origins: How the Earth Shaped Human History. Random House. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-1-4735-4733-9.

- ^ Dartnell, Lewis (2019-01-31). Origins: How the Earth Shaped Human History. Random House. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-4735-4733-9.

- ^ Dartnell, Lewis (2019-01-31). Origins: How the Earth Shaped Human History. Random House. p. 347. ISBN 978-1-4735-4733-9.

- ^ Dartnell, Lewis (2019-01-31). Origins: How the Earth Shaped Human History. Random House. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-4735-4733-9.

- ^ Dartnell, Lewis (2019-01-31). Origins: How the Earth Shaped Human History. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4735-4733-9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Fukuyama, Francis (2012-03-27). The Origins of Political Order: From Prehuman Times to the French Revolution. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-374-53322-9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dartnell, Lewis (2019-01-31). Origins: How the Earth Shaped Human History. Random House. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-4735-4733-9.

- ^ Daniel, Glyn (2003) [1968]. The First Civilizations: The Archaeology of their Origins. New York: Phoenix Press. xiii. ISBN 1-84212-500-1.

- ^ Daniel, Glyn (2003) [1968]. The First Civilizations: The Archaeology of their Origins. New York: Phoenix Press. pp. 9–11. ISBN 1-84212-500-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Holslag, Jonathan, author., A political history of the world : three thousand years of war and peace, pp. 33–34, ISBN 978-0-241-38466-4, OCLC 1080190517CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Dartnell, Lewis (2019-01-31). Origins: How the Earth Shaped Human History. Random House. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-4735-4733-9.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan, author., A political history of the world : three thousand years of war and peace, pp. 34–35, ISBN 978-0-241-38466-4, OCLC 1080190517CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Dartnell, Lewis (2019-01-31). Origins: How the Earth Shaped Human History. Random House. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-4735-4733-9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Holslag, Jonathan, author., A political history of the world : three thousand years of war and peace, pp. 39–40, ISBN 978-0-241-38466-4, OCLC 1080190517CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Holslag, Jonathan (2018). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin Books, Limited. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-241-35204-5.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin Books, Limited. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-241-35204-5.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin Books, Limited. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-241-35204-5.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin Books, Limited. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-241-35204-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Holslag, Jonathan (2018). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin Books, Limited. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-241-35204-5.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. pp. 109–110. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. pp. 149–150. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. pp. 244–245. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 249. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 252. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 253. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Daniels, Patrica S; Stephen G Hyslop; Douglas Brinkley; Esther Ferington; Lee Hassig; Dale-Marie Herring (2003). Toni Eugene (ed.). Almanac of World History. National Geographic Society. p. 56. ISBN 0-7922-5092-3.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan, A political history of the world : three thousand years of war and peace, McMillan, Roy, 1963-, [Place of publication not identified], p. 46, ISBN 978-0-241-38466-4, OCLC 1080190517

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin Books, Limited. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-241-35204-5.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Holslag, Jonathan (2018). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin Books, Limited. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-241-35204-5.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin Books, Limited. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-241-35204-5.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin Books, Limited. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-241-35204-5.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 185. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 269. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Holslag, Jonathan, author. (3 October 2019). Political history of the world : three thousand years of war and peace. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-0-241-39556-1. OCLC 1139013058.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin Books, Limited. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-241-35204-5.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin Books, Limited. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-241-35204-5.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin Books, Limited. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-241-35204-5.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin Books, Limited. pp. 157–158. ISBN 978-0-241-35204-5.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin Books, Limited. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-241-35204-5.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin Books, Limited. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-241-35204-5.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 260. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 423. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 424. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 425. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 426. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Marsh, Erik (2019). "Temporal Inflection Points in Decorated Pottery: A Bayesian Refinement of the Late Formative Chronology in the Southern Lake Titicaca Basin, Bolivia". Latin American Antiquity. 30 (4): 798–817. doi:10.1017/laq.2019.73. S2CID 213080578.

- ^ Hassig 1988

- ^ "Julie Adkins, "Mesoamerican Anomaly? The Pre-Conquest Tarascan State", Robert V. Kemper, Faculty papers, Southern Methodist University. On line". smu.edu. Archived from the original on 19 December 2009. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ Benn, Charles D. (2004). China's Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty. Oxford University Press. p. 1. ISBN 0-19-517665-0. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- ^ Daniels, Patrica S; Stephen G Hyslop; Douglas Brinkley; Esther Ferington; Lee Hassig; Dale-Marie Herring (2003). Toni Eugene (ed.). Almanac of World History. National Geographic Society. pp. 118–21. ISBN 0-7922-5092-3.

- ^ Benn, Charles D. (2004). China's Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty. Oxford University Press. pp. ix. ISBN 0-19-517665-0. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- ^ Herrmann, Albert (1970). Historical and Commercial Atlas of China. Ch'eng-wen Publishing House. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- ^ Hucker, Charles O. (1995). China's Imperial Past: An Introduction to Chinese History and Culture. Stanford University Press. p. 147. ISBN 0-8047-2353-2. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- ^ Daniels, Patrica S; Stephen G Hyslop; Douglas Brinkley; Esther Ferington; Lee Hassig; Dale-Marie Herring (2003). Toni Eugene (ed.). Almanac of World History. National Geographic Society. pp. 134–5. ISBN 0-7922-5092-3.

- ^ Diamond. Guns, Germs, and Steel. p. 367.

- ^ The Mongols and Russia, by George Vernadsky

- ^ Gregory G.Guzman "Were the barbarians a negative or positive factor in ancient and medieval history?", The Historian 50 (1988), 568–70.

- ^ Allsen. Culture and Conquest. p. 211.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 361. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ "The Islamic World to 1600: The Golden Horde". University of Calgary. 1998. Archived from the original on 13 November 2010. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ Michael Biran. Qaidu and the Rise of the Independent Mongol State in Central Asia. The Curzon Press, 1997, ISBN 0-7007-0631-3

- ^ The Cambridge History of China: Alien Regimes and Border States. p. 413.

- ^ Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 127.

- ^ Allsen. Culture and Conquest. pp. xiii, 235.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 419. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 419. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 420. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Howard-Johnston (2006), 9: "[Heraclius'] victories in the field over the following years and its political repercussions ... saved the main bastion of Christianity in the Near East and gravely weakened its old Zoroastrian rival."

- ^ Haldon (1997), 43–45, 66, 71, 114–15

- ^ Ambivalence toward Byzantine rule on the part of miaphysites may have lessened local resistance to the Arab expansion (Haldon [1997], 49–50).

- ^ Liska (1998), 170

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 287. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 287. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 288. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 338. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 341. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 343. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 343. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 297. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 344. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 345. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 348. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- ^ Mawer, Allen (1913). The Vikings. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 095173394X.