Putin's Palace

| "Putin's Palace" | |

|---|---|

"Дворец Путина" | |

Palace entrance, 2011 | |

| |

| Alternative names | Residence at Cape Idokopas |

| General information | |

| Type | Palace |

| Architectural style | Italianate |

| Location | Gelendzhik Urban Okrug, Krasnodar Krai, Russia |

| Construction started | 2005 |

| Cost | $1,350,000,000 (estimate) |

| Owner | Alexander Ponomarenko (claimed; since 2011) Arkady Rotenberg (claimed; since 2021) |

| Technical details | |

| Size | 17,691 square meters[1] |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | |

| Main contractor | [2] |

"Putin's Palace" (Russian: "Дворец Путина"), also known as the Residence at Cape Idokopas,[3] is an Italianate palace complex located on the Black Sea coast near Gelendzhik, Krasnodar Krai, Russia. The cost of the build is estimated to be over 100 billion rubles ($1.35 billion) at 2021 prices.[4]

Russian businessman Arkady Rotenberg has said that he owns the building, which will be used as an aparthotel.[5][6] Rotenberg has close ties to Russian President Vladimir Putin, and it has been alleged that the palace was built for the president's personal use.

The building drew substantial public attention in 2021, when Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny's Anti Corruption Foundation (ACF) released a similarly-named Putin's Palace investigative movie.

Location and buildings[]

The residence is located on Cape Idokopas, near the village of .[8] Cape Idokopas (Russian: Мыс Идокопас) is a promontory on the Black Sea coast of Russia near Gelendzhik, Krasnodar Krai. The headland is lined with cliffs but is mostly flat on its summit, which is heavily forested with pitsunda pine trees. It is bordered by a reef that makes offshore navigation hazardous.[9] The residence overlooks Russia's Black Sea coast, and is built on a block of land with a total area of 74 hectares.[10] The airspace around the palace (see image) is regulated as Prohibited Special Use Airspace P116 (i.e. a no-fly zone), for which the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) stated was to protect an FSB border-post in the area from increased foreign intelligence activity.[7]

The buildings on the palace complex include a house with an area of 17,700 m², an arboretum, a greenhouse, a helipad, an ice palace, a church, an amphitheater, a "tea house" (guest house), a gas station, an 80-meter bridge and a special tunnel inside the mountain with a tasting room.

Inside the main building are a swimming pool, aquadiskotheque arrangement, spa, saunas, Turkish baths, meat and fish, vegetable and dessert shops, a warehouse, a reading room, a music lounge, a hookah bar, a theater and a cinema, a wine cellar, a casino, and about a dozen guest bedrooms. The master bedroom is 260 m² in size.[11]

The house is designed by the Italian architect Lanfranco Cirillo, who has designed properties for many of Russia's elite.[12]

Ownership[]

Russian government official Vladimir Kozhin told reporters from the Russian daily Kommersant that the Russian government had approved the construction of the estate by the Lirus group, and that the government maintained a stake in the project until 2008, when it sold its share.[13]

In March 2011, it was reported that Alexander Ponomarenko, a businessman and billionaire who made his money in sea ports, banking, commercial real estate and airport construction, acquired the company "Idokopas" which owned the palace.[14][15] At the time of the purchase, Idokopas owned around 67 hectares of recreational land near the settlement of Praskoveyeka, including a guesthouse complex amounting to 26,000 square meters. Ponomarenko also said he had bought a second company, "Lazurnaya Yagoda", which owned 60 hectares of agricultural land near Divnomorsk, a settlement 13 kilometers from Praskoveyevka. Ponomarenko bought the unfinished complex from Shamalov and his partners.[16] At the time of the purchase, Ponomarenko did not disclose the value of the deal, but hinted he had been able to purchase the property for a very good price – the asset was heavily encumbered with debts and the developers had run out of money to complete the project.[14] When asked about the projected value of the complex once complete, he conceded that suggestions it could be as much as $350 million "were close to the truth".[14][17][18] According to Vedomosti, however, experts estimated the value of the property at $20 million.[19] In July 2011, "Lazurnaya Yagoda" was sold to SVL Group, controlled by Boris Titov, the owner of champagne factory "Abrau-Durso".[20] Ponomarenko's media representatives told Forbes in 2021 that Ponomarenko had withdrawn from the project in 2016.[21]

On 11 May 2016, RBC reported that Alexei Vasilyuk (Russian: Алексей Василюк) through his ownership of the Moscow registered LLC "South Citadel" (Russian: ООО «Южная цитадель») has exclusive rights since 25 March 2016 to the water along the coastline between Cape Idokopas and Divnomorskoye for the production of mussels and oysters and that on 20 April 2016 "South Citadel" received a 25 year lease to two land plots totaling 422.1 hectares (1,043 acres) along the Black Sea next to "Putin's Palace".[22][23] The RBC article also stated that Ponomarenko is the owner of "Putin's Palace" through his Komplex LLC (Russian: ООО «Комплекс») which is the owner of the land under "Putin's Palace" since May 2013 and the owner of the structure "Putin's Palace" since March 2015 and that the British Virgins Islands firm Savoyan Investments Limited has been the owner of Complex LLC since September 2013.[23] According to a 13 May 2016 The Moscow Times article, the exclusive ownership of the nearby coastline is to prevent ships from approaching the coastline near "Putin's Palace".[22] On 3 March 2017, Alexander Ponomarenko obtained a 100% stake in "South Citadel" and thus obtained an additional two plots of land next to "Putin's Palace" and had the exclusive rights to the water along the coastline near "Putin's Palace".[24]

On 30 January 2021, the billionaire Arkady Rotenberg, who has close links to Putin, said that he had purchased the estate "a few years ago." He also said that the property when completed would become an apartment hotel.[6][5]

Corruption claims[]

Kolesnikov letter[]

In 2010, Russian businessman Sergei Kolesnikov wrote an open letter to Dmitry Medvedev, at that time the Russian President, stating that a dentist named Nikolai Shamalov was building a grand Black Sea estate for Putin[25] or Medvedev.[10] Kolesnikov said the construction of the estate was draining funds available for his work, which included the state-commissioned renovations of hospitals in collaboration with Shamalov and businessman .[25] Kolesnikov further said that he had worked on the estate project until he was removed because he voiced concerns about corruption, that the estate was still under construction, and the cost was one billion dollars, funded by bribery and theft.[10]

In 2011, the Novaya Gazeta wrote that it had obtained a contract for the palace signed by the presidential property manager in 2005, when Putin was the Russian president.[25] A website called the "Russian Wikileaks," RuLeaks.Ru, posted photographs of the estate, but could not confirm its ownership.[26] Medvedev replied that neither he nor Putin had any relationship to the property.[27]

Speaking to the BBC in 2012, Kolesnikov said that the estate was still under construction, and that the project was being organized sometimes by Shamalov, or sometimes by a deputy of the president, Igor Sechin.[8] Kolesnikov said that Shamalov never questioned his role, adding, "There was a tsar - and there were slaves, who didn't have their own opinion."[8] According to the BBC, the estate was owned by a company Shamalov partly owned, and it was unclear if Putin had any relationship to the property.[8]

Financing claims[]

In Kolesnikov's initial letter and in subsequent media interviews, including to Novaya Gazeta, David Ignatius of The Washington Post and Masha Gessen of Snob.ru, he provided an account of how the construction of the estate was financed by corruption.[28][29] Kolesnikov said that in early 2000, Nikolai Terentievich Shamalov, a representative of the multinational company Siemens AG in North West Russia and somebody thought close to Russia's new President Vladimir Putin, approached Kolesnikov with a business proposition. The two men had known each other through business since 1993–1994, when Kolesnikov was deputy director general of Petromed, a St. Petersburg-based firm that specialised in the procurement of medical supplies. It was also through Petromed that Kolesnikov had got to know Putin, on whose behalf Shamalov said he made the approach. Putin had been head of the St. Petersburg Council on External Economic affairs which when Petromed became a private company in 1992 held a 51% stake.[29]

Kolesnikov told Masha Gessen that Putin held 94% of shares in Rosinvest, with Kolesnikov, Shamalov and Dmitry Vladimirovich Gorelov (director of Petromed and another friend of Putin from his time in Saint Petersburg) taking 2% each. Rosinvest's interests included shipbuilding, construction, and lumber/timber processing.[29] Kolesnikov is reported as saying that Abramovich and the other donors to health projects acted 'nobly', implying they were unaware that a significant proportion of their donations was being diverted into an investment vehicle allegedly run for the benefit of the President and his partners in Rosinvest. This is despite the huge sums involved and disputed claims that the relationship between Putin and Abramovich has been very close.[30]

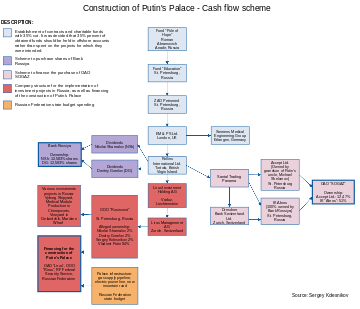

The chart below shows the scheme of interaction between companies and cash flows involved in financing of the construction, according to Kolesnikov.[31]

Investigations[]

In February 2011, members of the group "Environmental Watch for the North Caucasus" and a journalist visited the site to investigate concerns that the construction violated laws protecting the area's ecology. They said that they were harassed and detained by members of the Federal Protective Service (FSO), the agency responsible for guarding state property and high-ranking officials.[32] Despite the confiscation of their equipment they were able to publish additional photographs of the site.[33] Activists made another sortie into the property in June 2011, when they claimed to have found an illegally constructed marina.[34]

RBC investigation[]

The 11 May 2016 RBC article "Oyster farming will begin in front of the "Putin's palace" near Gelendzhik" (Russian: Напротив «дворца Путина» под Геленджиком начнут разводить устриц) revealed that Ponomarenko is the owner of "Putin's Palace".[22][23] The publishing of the RBC article contributed to Mikhail Prokhorov, who has the majority ownership of the RBK Group after he purchased a 51% stake in it in 2009, to fire Maxim Solus, the editor-in-chief of RBC newspaper, which further resulted in the resignations of both Roman Badanin, rbc.ru's chief editor, and Yelizaveta Osetinskaya, RBC's chief editor.[22]

FBK investigation[]

| External video | |

|---|---|

On 19 January 2021, two days after Alexei Navalny was detained by Russian authorities upon his return to Russia, an investigation by him and his Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK) was published accusing President Vladimir Putin of using fraudulently obtained funds to build the estate for himself in what he called "the world's biggest bribe." Navalny said that the estate is 39 times the size of Monaco and cost over 100 billion rubles ($1.35 billion) to construct. His video showed aerial footage of the estate via a drone and a detailed floorplan of the palace that Navalny said was given by a contractor, which he compared to photographs from inside the palace that were leaked onto the Internet in 2011. He also detailed an elaborate corruption scheme allegedly involving Putin's inner circle that allowed Putin to hide billions of dollars to build the estate.[35][36][37]

After Navalny's arrest and the release of his video, protests in support of Navalny began on 23 January 2021. In response to the claims, Putin said that the palace had never belonged either to him or his family.[38][39]

The BBC Russian Service spoke to several construction workers who said they worked on the palace between 2005 and 2020, confirming several of the allegations made in the FBK investigation, including that the palace was being rebuilt due to mold.[40]

Meduza investigation[]

Journalists from the online newspaper Meduza interviewed people who were involved in the construction of the residence.[3] Many interviewees said the residence is connected with Putin and is guarded by the FSO, who also supervise construction. Meduza had documents with the names and signatures of the FSO employees, including Colonel Oleg Kuznetsov. The article described vast and extravagant luxuries in the estate.[41]

Mash channel[]

On 29 January 2021, the pro-Kremlin[5][42] Mash Telegram channel gained access to the palace, confirming that the palace was under construction. While it attempted to contradict Navalny's claims, Navalny's team said that it confirmed their reporting that the palace had to be redone due to mold.[43]

Gallery[]

Exterior (11 November 2010)

Gardens

Main hall

Main hall

One of the bedrooms

One of the bathrooms

Courtyard (curtains and chandeliers are visible in all windows)

Swimming pool near the aqua-discotheque

See also[]

- 2021 Russian protests

- Mezhyhirya Residence, the residence of Viktor Yanukovych, former Prime Minister and President of Ukraine

- Millerhof

- Novo-Ogaryovo, the official residence of the President of Russia

References[]

- ^ Ilyushina, Mary. "Navalny releases investigation into decadent billion-dollar 'Putin palace". www.cnn.com. CNN. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ "Бизнесмен Колесников в первом видеоинтервью объяснился по поводу "дворца Путина"" [Businessman Kolesnikov in the first video interview explained about "Putin's palace"]. NEWSru (in Russian). 25 February 2011. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Yapparova, Lilia; Dmitriev, Denis; Kovalev, Alexey; Maglov, Mikhail (29 January 2021). Igumenov, Valery (ed.). "It's good to be the president". Meduza. Scanner Project; Translated by Kevin Rothrock. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ * Dawisha, Karen (2015). Putin's kleptocracy : who owns Russia?. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. XII. ISBN 978-1-4767-9520-1. OCLC 894747004. Archived from the original on 7 June 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- Grey, Stephen; Bush, Jason; Anin, Roman (21 May 2014). "Comrade Capitalism: Putin's Palace". Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- Roache, Madeline (29 January 2021). "How Navalny Uncovered Putin's $1.3 Billion Palace". Time. Archived from the original on 2 February 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- Shmagun, Olesya (6 October 2017). "The Magic Isle: How Wealthy Russians Use an Offshore Territory to Avoid Taxes on Private Jets". Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- Kaminska, Izabella (20 January 2021). "Further reading". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- Oliphant, Roland (9 March 2011). "Oligarch Buys "Putin's Palace"". The St. Petersburg Times. Archived from the original on 29 March 2012. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- "Alexei Navalny: Millions watch jailed critic's 'Putin palace' film". BBC News. 20 January 2021. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Russian billionaire Arkady Rotenberg says 'Putin Palace' is his". BBC News. 30 January 2021. Archived from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Putin's former judo partner says he owns palace linked to Russian leader". www.theguardian.com. The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Roth, Andrew (27 January 2021). "No-fly zone over Putin-linked palace is due to Nato spies, says FSB". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Whewell, Tim (4 May 2012). "Putin's palace? A mystery Black Sea mansion fit for a tsar". BBC. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ United States Hydrographic Office (1927). Black Sea Pilot: The Dardanelles, Sea of Marmara, Bosporus, Black Sea and Sea of Azov. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Osborn, Andrew (14 February 2011). "Vladimir Putin 'has £600 million Italianate palace'". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 August 2011. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ^ "Параллельная реальность". newtimes.ru. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ Korobov, Pavel (April 2011). Kashin, Oleg (ed.). "Vot chego-chego, a kontrolyorov u nas khvataet" [Interview with Vladimir Kozhin: 'We have enough inspectors there'] (in Russian). Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Friendly Oligarch Buys 'Putin' Palace Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, themoscowtimes.com, 4 March 2011

- ^ Alexander Ponomarenko Archived 30 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine, forbes.com, 18 March 2015

- ^ Staff, Our Foreign (3 March 2011). "'Putin palace' sells for $350 million". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 March 2011. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- ^ "'Putin's Palace,' $350 Million Mansion Reportedly Owned By Russian Prime Minister, Sold To Tycoon". The Huffington Post. 4 March 2011. Archived from the original on 11 March 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ^ Oliphant, Roland (9 March 2011). "Oligarch Buys 'Putin's Palace'". The St. Petersburg Times. Archived from the original on 29 March 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ^ The so-called 'Putin Palace' is sold Archived 3 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, themoscownews.com, 03/03/2011

- ^ "Абрау-Дюрсо" пришлось ко дворцу Борис Титов купил виноградники санатория, считавшегося дачей премьер-министра kommersant.ru, 6 July 2011

- ^ "Sheremetyevo announced the withdrawal of a businessman from the Forbes list from the "palace" project on the Black Sea". Forbes. 26 January 2021. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Ardayeva, Anya (13 May 2016). "Three Top Managers Leave Russia's RBC Media". The Moscow Times. Archived from the original on 14 May 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Бурлакова, Екатерина (Burlakova, Ekaterina); Пузырев, Денис (Puzyrev, Denis) (11 May 2016). "Напротив "дворца Путина" под Геленджиком начнут разводить устриц: ООО "Южная цитадель" получило для выращивания устриц и мидий 1 тыс. га акватории у мыса Идокопас под Геленджиком, у так называемого дворца Путина. Владелец "Южной цитадели" ранее работал в компании, управлявшей дворцом" [Oyster farming will begin in front of the "Putin's palace" near Gelendzhik: LLC “Yuzhnaya citadel” received 1,000 hectares of water area for growing oysters and mussels near Cape Idokopas near Gelendzhik, near the so-called Putin's palace. The owner of South Citadel previously worked for the company that operated the palace.]. «РБК» (RBC) (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2 February 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Бурлакова, Екатерина (Burlakova, Ekaterina) (9 March 2017). "У устрично-мидиевой фермы в Геленджике тот же хозяин, что и у "дворца Путина": Хозяйство Александра Пономаренко уже приступило к производству моллюсков" [The oyster-mussel farm in Gelendzhik has the same owner as the "Putin's palace": The farm of Alexander Ponomarenko has already started the production of shellfish]. Vedomosti (in Russian). Archived from the original on 8 February 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Reuters Investigates [1] Archived 12 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 16 October 2014

- ^ Feifer, Gregory (21 January 2011). "'Putin Palace' Pics: It's Good To Be The PM". Transmission Blog. Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ "Хреков не комментирует публикации о дворце, строящемся на Черном море". Ria Novosti. 14 February 2011. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ Ignatius, David (23 December 2010). "Sergey Kolesnikov's tale of palatial corruption, Russian style". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 20 January 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Сергей Колесников: Почему я рассказал про Дворец Путина. "Мы перешли границу между добром и злом в 2009 году" [Sergey Kolesnikov: Why I told her about Putin's Palace. "We crossed the border between good and evil in 2009"]. Snob.ru (in Russian). 23 June 2011. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- ^ Harding, Luke (1 December 2010). "WikiLeaks cables: Roman Abramovich denies links with Vladimir Putin". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 20 September 2013. Retrieved 23 July 2011.

- ^ Kolesnikov, Sergei. "Scheme of interaction between companies and cash flows (English, picture)" (PDF). Kolesnikov Palace Documents. hosted by Havighurst Center for Russian and Post-Soviet Studies. Oxford. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 May 2015. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- ^ АКТИВИСТЫ ЭКОЛОГИЧЕСКОЙ ВАХТЫ И ЖУРНАЛИСТ ЗАБЛОКИРОВАНЫ СОТРУДНИКАМИ ФСО, ПОГРАНСЛУЖБЫ И МИЛИЦИИ ВОЗЛЕ ПРЕДПОЛАГАЕМОЙ ДАЧИ ПУТИНА НА МЫСЕ ИДОКОПАС [Environmental activists and Watch staff reporter detained by FSO, and border policemen nearby imply Putin's dacha at Cape Idokopas]. Environmental Watch on North Caucasus (in Russian). 11 February 2011. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- ^ Активисты ЭкоВахты посетили дворец Путина на мысе Идокопас [EcoWatch Activists visited Putin's palace at Cape Idokopas]. Environmental Watch on North Caucasus (in Russian). 11 February 2011. Archived from the original on 10 August 2011. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- ^ "Environmentalists crash 'Putin's seaside palace'". France 24. 7 May 2011. Archived from the original on 9 July 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2011.

- ^ "Navalny Targets 'Billion-Dollar Putin Palace' in New Investigation". The Moscow Times. 19 January 2021. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ^ "ФБК опубликовал огромное расследование о "дворце Путина" в Геленджике. Вот главное из двухчасового фильма о строительстве ценой в 100 м��ллиардов". Meduza.io. 19 January 2021. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ^ "ФБК опубликовал расследование о "дворце Путина" размером с 39 княжеств Монако". tvrain.ru. 19 January 2021. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ^ "Vladimir Putin: Palace in Navalny report 'doesn't belong to me' | DW | 25.01.2021". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 19 February 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ "Putin denies Navalny allegation he owns Black Sea palace". France24. 25 January 2021. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ "'Putin's palace': Builders' story of luxury, mould and fake walls". BBC News. 12 February 2021. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ Yapparova, Lilia; Dmitriev, Denis; Kovalev, Alexey; Maglov, Mikhail. Igumenov, Valery (ed.). "Если человек — президент, ему все можно" [If a person is a president, he can do anything]. Meduza (in Russian). Edited by Alexey Kovalev. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ Khurshudyan, Isabelle; Dixon, Robyn (31 January 2021). "Russia cracks down on Navalny protests, locking down city centers and arresting thousands". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "Kremlin-Aligned Media Confirms 'Putin Palace' Still Under Construction". The Moscow Times. 29 January 2021. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

External links[]

Media related to Residence at Cape Idokopas at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Residence at Cape Idokopas at Wikimedia Commons- "Putin's palace. History of world's largest bribe". 19 January 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021 – via YouTube.

- 2005 establishments in Russia

- Buildings and structures in Krasnodar Krai

- Corruption in Russia

- Hotels in Russia

- Italianate architecture

- Palaces in Russia

- Vladimir Putin