Real tennis

Real tennis – one of several games sometimes called "the sport of kings" – is the original racquet sport from which the modern game of tennis (originally called "lawn tennis") is derived. It is also known as court tennis in the United States,[1] formerly royal tennis in England and Australia,[2] and courte-paume in France (to distinguish it from longue-paume, and in reference to the older, racquetless game of jeu de paume, the ancestor of modern handball and racquet games). Many French real tennis courts are at jeu de paume clubs.

The term real was first used by journalists in the early 20th century as a retronym to distinguish the ancient game from modern lawn tennis (even though, at present, the latter sport is seldom contested on lawns outside the few social-club-managed estates such as Wimbledon).

There are more than 50 active real tennis courts in the world, located in the United Kingdom, Australia, the United States and France.[3] Other countries have currently disused courts, such as the two in the Republic of Ireland. The sport is supported and governed by various organizations around the world.

Game description[]

The rules and scoring are similar to those of lawn tennis, which derives from real tennis, but are more complex. In both sports game scoring is by fifteens ("40" being short for the original forty-five). However, in real tennis, six games wins a set, without the need for a two-game margin as in lawn tennis[4] although some tournaments require more games (as many as 10) to win, usually playing one, single set. A match is typically best of three sets, except matches between men in the major open tournaments, which are best of five sets.

Equipment[]

Unlike latex-based technology underlying the modern lawn tennis ball, the game uses a cork-cored ball which is very close in design to the original balls used in the game. The 2+1⁄2-inch (64 mm) diameter balls are handmade and consist of a core made of cork with fabric tape tightly wound around it, compacted by outer windings of string, and covered with a hand-sewn layer of heavy, woven, woollen cloth, traditionally Melton cloth (not felt, which is unwoven and not strong enough to last as a ball covering). The balls were traditionally white, but around the end of the 20th century "optic yellow" was introduced for improved visibility, as had been done years earlier in lawn tennis. The balls are much less bouncy than lawn tennis balls, and weigh about 2+1⁄2 ounces (71 grams) (lawn tennis balls typically weigh 2 ounces (57 g)).

The 27-inch (690 mm) short, asymmetrical racquets are made of wood and use very tight nylon strings to cope with the heavy balls. The racquet oval is shaped to make it easier to strike balls close to the floor or in corners, and to facilitate a fast shot with a low trajectory that is difficult for an opponent to return. There are two companies in the world hand-crafting these racquets: Grays of Cambridge (UK) and Gold Leaf Athletics (US).

Courts[]

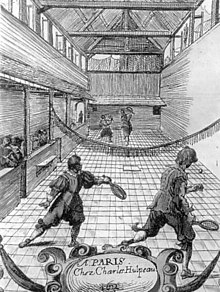

There are two basic designs in existence today: jeu quarré, which is an older design, and jeu à dedans. The court at Falkland Palace is a jeu quarré design which unlike jeu à dedans court lacks a tambour and dedans. Mary, Queen of Scots became especially fond of the game, and it is said that she scandalised the people of Scotland by wearing men's breeches to play. The more common real tennis court (jeu à dedans) is a very substantial building (encompassing an area wider and longer than a lawn tennis court, with high walls and a ceiling lofty enough to contain all but the highest lob shots). It is enclosed by walls on all four sides, three of which have sloping roofs, known as "penthouses", beneath which are various openings ("galleries", from which spectators may view the game and which also play a role in scoring points), and a buttress that intrudes into the playing area (tambour) off which shots may be played. There are no "standard dimensions" for courts. Most are about 110 by 39 feet (34 m × 12 m) above the penthouses, and about 96 by 32 feet (29.3 m × 9.8 m) on the playing floor, varying by a foot or two per court. They are doubly asymmetric: each end of the court differs in shape from the other, and the left and right sides of the court are also different.

Manner of play[]

The service is always made from the same end of the court (the "service" end); a good service must touch the side penthouse (above and to the left of the server) on or over the white service line on the receiver's ("hazard") side before touching the floor in a marked area on that side. There are numerous and widely varying styles of service. These are given descriptive names to distinguish them – examples are "railroad", "bobble", "poop", "piqué", "boomerang", and "giraffe".[5][citation needed]

The game has many other complexities. For instance, when the ball bounces twice on the floor at the service end, the serving player does not generally lose the point. Instead a "chase" is called where the ball made its second bounce and the server gets the chance, later in the game, to "play off" the chase from the receiving end; but to win the point being played off, their shot's second bounce must be further from the net (closer to the back wall) than the shot they originally failed to reach. A chase can also be called at the receiving ("hazard") end, but only on the half of that end nearest the net; this is called a "hazard" chase.

Those areas of the court in which chases can be called are marked with lines running across the floor, parallel to the net, generally about 1 yard (0.91 m) apart – it is these lines by which the chases are measured. Additionally, a player can gain the advantage of serving only through skillful play (viz. "laying" a "chase", which ensures a change of end). This is in stark contrast to lawn tennis, where players alternately serve and receive entire games. In real tennis the service can only change during a game, and it is not uncommon to see a player serve for several consecutive games till a chase be made. Indeed, in theory, an entire match could be played with no change of service, the same player serving every point.

The heavy, solid balls take a great deal of spin, which often causes them to rebound from the walls at unexpected angles. For the sake of a good chase (close to the back wall), it is desirable to use a cutting stroke, which imparts backspin to the ball, causing it to come sharply down after hitting the back wall.

Another twist to the game comes from the various window-like openings ('galleries') below the penthouse roofs that, in some cases, offer the player a chance to win the point instantly when the ball is hit into the opening (in other cases, these windows create a ""). Effectively, these are "goals" to be aimed for. The largest such opening, located behind the server, is called the "" and must often be defended on the volley from hard hit shots, called "forces", coming from the receiving ("hazard") side of the court. The resulting back-court volleys and the possibility of hitting shots off the side walls and the sloping penthouses give many interesting shot choices not available in lawn tennis. Moreover, because of the weight of the balls, the small racquets, and the need to defend the rear of the court, many lawn tennis strategies, such as playing with topspin, and serve-and-volley tactics, are ineffective.

History[]

The term "tennis" is thought to derive from the French word tenez, which means "take heed" – a warning from the server to the receiver. Real tennis evolved, over three centuries, from an earlier ball game played around the 12th century in France. This had some similarities to palla, fives, Spanish pelota or handball, in that it involved hitting a ball with a bare hand and later with a glove. This game may have been played by monks in monastery cloisters, but the construction and appearance of courts more resemble medieval courtyards and streets than religious buildings. By the 16th century, the glove had become a racquet, the game had moved to an enclosed playing area, and the rules had stabilized. Real tennis spread across Europe, with the Papal Legate reporting in 1596 that there were 250 courts in Paris alone, near the peak of its popularity in France.[6]

Royal interest in England began with Henry V (reigned 1413–22) but it was Henry VIII (reigned 1509–47) who made the biggest impact as a young monarch, playing the game with gusto at Hampton Court on a court he had built in 1530 and on several other courts in his palaces. His second wife Anne Boleyn was watching a game of real tennis when she was arrested and it is believed that Henry was playing tennis when news was brought to him of her execution.[7] Queen Elizabeth I was a keen spectator of the game. During the reign of James I (1603–25), there were 14 courts in London.[8]

In France, François I (1515–47) was an enthusiastic player and promoter of real tennis, building courts and encouraging play among both courtiers and commoners. His successor, Henry II (1547–59), was also an excellent player and continued the royal French tradition. The first known book about tennis, Trattato del Giuoco della Palla was written during his reign, in 1555, by an Italian priest, Antonio Scaino da Salo. Two French kings died from tennis-related episodes – Louis X of a severe chill after playing and Charles VIII after striking his head on the lintel of a door leading to the court in the royal Château at Amboise. King Charles IX granted a constitution to the in 1571, creating a career for the 'maître paumiers' and, establishing three levels of professionals – apprentice, associate, and master. The first codification of the rules of real tennis was written by a professional named Forbet and published in 1599.[9]

The game thrived among the 17th-century nobility in France, Spain, Italy, the Netherlands, and the Habsburg Empire, but suffered under English Puritanism, as it was heavily associated with gambling. By the Age of Napoleon, the royal families of Europe were besieged and real tennis, a court game, was largely abandoned.[10] Real tennis played a role in the history of the French Revolution, through the Tennis Court Oath, a pledge signed by French deputies in a real tennis court, which formed a decisive early step in starting the revolution.

An epitaph in St Michael's Church, Coventry, written circa 1705 read, in part:[11]

Here lyes an old toss'd Tennis Ball:

Was racketted, from spring to fall,

With so much heat and so much hast,

Time's arm for shame grew tyred at last.

During the 18th century and early 19th century, as real tennis declined, new racquets sports emerged in England: rackets and squash racquets.

There is documented history of courts existing in the German states from the 17th century, the sport evidently died out there during or after World War II.[citation needed]

In Victorian England, real tennis had a revival, but broad public interest later shifted to the new, much less difficult outdoor game of lawn tennis, which soon became the more popular sport, and was played by both genders (real tennis players were almost exclusively male). Real tennis courts were built in Hobart, Tasmania (1875) and in the United States, starting in 1876 in Boston, and in New York in 1890, and later at athletic clubs in several other cities. Real tennis greatly influenced the game of stické, which was invented in the 19th century and combined aspects of real tennis, lawn tennis and rackets.

Real tennis has the longest line of consecutive world champions of any sport in the world, dating from 1760.

Victorian court master-builder[]

A forgotten master of designing, building and restoring real tennis courts was the British Fulham-based builder, Joseph Bickley (1835–1923).[12] He became a specialist around 1889 and patented a plaster mix to withstand condensation and dampness.[13][14] Examples of his surviving work include: The Queen's Club, Lord's, Hampton Court Palace, Jesmond Dene, Newmarket, Moreton Hall, Warwickshire and Petworth House.[15] There are also examples of his projects in Scotland and in the United States.[16][17]

Locations[]

There are more than 50 real tennis courts in the world, and over half of these are in Britain.

United Kingdom

- Bristol and Bath Tennis Club, Bristol: 1 court in use

- Cambridge University Real Tennis Club, Cambridge, Cambridgeshire: 2 courts in use

- Canford, Dorset: Sir Ivor Guest opened the court at Canford in 1879, although there had been an earlier court built in the grounds of the manor house dating back to 1541. It is still in use in a building that belongs to Canford School and also now houses four squash courts: 1 court in use

- The Fairlawne Estate, Plaxtol, Kent: 1 court (private)

- Falkland Palace, Fife, Scotland: The oldest court in the world for real tennis, opened in 1539, currently home of the Falkland Palace Royal Tennis Club : 1 quarré court in use

- Hardwick House, Whitchurch-on-Thames, Oxfordshire: 1 court in use

- Hatfield House Tennis Club, Hatfield, Hertfordshire: 1 court in use

- Hyde Tennis Club, Bridport, Dorset: 1 court in use

- Jesmond Dene, Newcastle: The court is situated on Matthew Bank near Jesmond Dene park, was built in 1894 for Sir Andrew Noble, the then-owner of Jesmond Dene House as a private court. It is now a listed building.[18]: 1 court in use

- Leamington Spa Tennis Court Club, built in 1846, it is the oldest purpose built real tennis club in the world: 1 court in use

- The Manchester Club: Originated in 1874, the current club on Blackfriars Road was built in 1880: 1 court in use

- Marylebone Cricket Club, St John's Wood, London: 1 court in use

- Merton Street tennis court, Oxford, built 1798, on the site of courts dating back to c.1595: 1 court in use

- Middlesex University Real Tennis Club, Hendon, London: 1 court in use

- Moreton Morrell Tennis Court Club, Moreton Morrell, Warwickshire: 1 court in use

- Newmarket and Suffolk Real Tennis Club, Newmarket, Suffolk: 1 court in use

- The Oratory School, Woodcote. Opened in 1954, a club situated in one of the leading catholic private schools in England. Its many sports facilities include court tennis: 1 court in use

- Petworth House, West Sussex: The first court was built in 1588, and the current one was built in 1872: 1 court in use

- Prested Hall Racket Club, Feering, Essex: 2 courts in use

- The Queen's Club, London: Opened in 1886, is the National headquarters of the governing body of real tennis, the Tennis and Rackets Association (T&RA), and hosts the British Open every year: 2 courts in use

- St. Peter's College, Radley. Opened in 2008, a court situated in one of the four remaining boys-only, boarding-only public schools (independent secondary schools) in the United Kingdom: 1 court in use

- Royal County of Berkshire Real Tennis Club, Holyport, Berkshire: 1 court in use

- Royal Tennis Court, Hampton Court Palace: The oldest surviving real tennis court in England, built on the site of an even older (1528) court in the 1620s, where the game can be watched by the general public during British Summer Time: 1 court in use

- Seacourt Tennis Club, Hayling Island, Hampshire: 1 court in use

- Wellington College, Sandhurst: Opened in 2016, the court is situated on the Wellington College estate: 1 court in use

United States of America:

- The Racquet Club of Philadelphia: Founded in 1889, current location constructed in 1907 by noted architect Horace Trumbauer.

- The Tennis and Racquet Club, Boston, MA: One of the oldest courts in the US, opened in 1902.

- The Racquet and Tennis Club, NY: New York City's famously exclusive tennis club, contains two real tennis courts, as well as a Racquets court, built in 1918.

- Prince's Court, McLean, VA: The newest court in the United States, opened in 1997 and has a glass viewing wall.

- National Tennis Club in Newport, RI: Located in the 'Newport Casino" now known as the International Tennis Hall of Fame.

- The Tuxedo Club in Tuxedo Park, NY: Private member-owned country club. Its many sports facilities include court tennis. The court building was constructed between 1890 and 1900.

- The Aiken Tennis Club: in Aiken, South Carolina, founded in 1898 by William C. Whitney political leader, financier and a key figure in the prominent Whitney family. The court building was constructed in 1902.

- The Racquet Club of Chicago: real tennis court was restored and re-opened in 2012 to complement the Racquets court and squash.

- Georgian Court University in Lakewood Township, New Jersey: built by George Jay Gould in 1899.

- Greentree: on the former Whitney estate on the north shore of Long Island (the town of Manhasset); now a dormant court.

France:

- Palace of Fontainebleau, France: the largest real tennis court in the world, and one of the few publicly owned.

- Paris, France: 74 rue Lauriston, Jeu de Paume. Known as 'Société Sportive du Jeu de Paume & de Racquets', this club was privately built in 1908 after the Jeu de Paume in the Tuileries gardens was transformed into an art gallery/ exhibition hall. [1]

- Bordeaux, France: a new court was built in 2019/2020 and is located in Mérignac. This modern facility replaces the 1st Merignac court which closed in 2013 whose predecessor was the original Bordeaux court which closed in 1978. [2]

Ireland:

- Lambay Island, Ireland: On the privately owned Lambay Island (approx 5 km off the coast near Dublin, Ireland).

Australia:

- Hobart Real Tennis Club, Tasmania: Founded in 1875 and the oldest real tennis club in Australia.

- Royal Melbourne Tennis Club, Australia: Founded in 1882, it is one of only five clubs in the world with more than one court.

- , in Victoria

- Sydney Real Tennis Club, in New South Wales (court closed in 2005). New court planned.

- , in Western Australia

- , Romsey, Victoria

Restored:

- Racquet Club of Chicago, a court built in 1922 was re-opened in In August 2012

New court projects in the USA:

- Washington, D.C : International Tennis Club of Washington (Prince's Court), as part of the Westwood Country Club in McLean, VA: [3]

- Charleston, South Carolina: as part of the Daniel Island Club aiming to be completed in late 2022: [4]

In literature[]

Tennis is mentioned in literature from the 16th century onwards. It is frequently shown in emblem books, such as those of Guillaume de La Perrière from 1539. Erasmus lets two students practice Latin during a game of tennis with a racquet in 1522, although the playing ground is not mentioned.[19] A 1581 translation of Ovid's Metamorphoses by Giovanni Andrea dell'Anguillara, printed in Venice in quarto form transforms the fatal discus game between Apollo and Hyacinth into a fatal game of real tennis, or "racchetta."

William Shakespeare mentions the game in Act I – Scene II of Henry V; the Dauphin, a French Prince, sends King Henry a gift of tennis-balls, out of jest, in response to Henry's claim to the French throne. King Henry replies to the French Ambassadors: "His present and your pains we thank you for: When we have matched our rackets to these balls, we will, in France, by God's grace, play a set [that] shall strike his father's crown into the hazard ... And tell the pleasant Prince this mock of his hath turn'd his balls to gun stones". Michael Drayton makes a similar reference to the event in his The bataille of Agincourt, published in 1627.

The Penguin book of Sick Verse includes a poem by William Lathum comparing life to a tennis-court:

If in my weak conceit, (for selfe disport),

The world I sample to a Tennis-court,

Where fate and fortune daily meet to play,

I doe conceive, I doe not much misse-say.

All manner chance are Rackets, wherewithall

They bandie men, from wall to wall;

Some over Lyne, to honour and great place,

Some under Lyne, to infame and disgrace;

Some with a cutting stroke they nimbly sent

Into the hazard placed at the end; ...

The Scottish gothic novel The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner by James Hogg (1824) describes a tennis match that degenerates into violence.

The detective story Dead Nick takes place in a tennis milieu. The title alludes to a shot that hits "the nick" (where the wall meets the floor), called "dead" because it then bounces very little and is frequently unreturnable.

Hazard Chase (1964), by Jeremy Potter, is a thriller-detective story featuring real tennis on the court at Hampton Court Palace. During the story the game is explained, and the book contains a diagram of a real tennis court. Jeremy Potter wrote historical works (including Tennis and Oxford (1994)), and was himself an accomplished player of the game, winning the World Amateur Over-60s Championship in 1986.

The First Beautiful Game: Stories of Obsession in Real Tennis (2006) by top amateur player Roman Krznaric contains a mixture of real tennis history, memoir and fiction, which focuses on what can be learned from real tennis about the art of living.

The Corpse on the Court (2013) is a mystery by Simon Brett. It features the recurring lead character of Jude learning many details about the sport from aficionados.

In The Chase by Ivor P. Cooper, in Ring of Fire II in the 1632 series, up-timers Heather Mason and Judy Wendell learn the sport from Thomas Hobbes. Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden is depicted as an aficionado of the game.

Sudden Death (2016), a novel by Alvaro Enrigue, is interstitched throughout with descriptions of a real tennis match between the Italian artist Caravaggio and the Spanish poet Quevedo. The details of play are interspersed among historical reflections on the game, descriptions of techniques for making the balls, quotations from contemporary sources, gambling that accompanied the game, the backgrounds of the participants and the strategy discussions between the players and their seconds. It is intentionally unclear which details are real and which are imagined by the author.

In film[]

This section does not cite any sources. (August 2018) |

Real tennis is featured in the film The Seven-Per-Cent Solution, a fictional meeting between Sherlock Holmes and Sigmund Freud. One of the film's plot points turns on Freud playing a grudge match with a Prussian nobleman (in lieu of a duel).

The film The French Lieutenant's Woman includes a sequence featuring a few points being played. Also The Three Musketeers (1973) and Ever After briefly feature the game. Although presented with varying degrees of accuracy, these films provide a chance to see the game played, which otherwise may be difficult to observe personally.

The Showtime series The Tudors (2007) portrays Henry the VIII playing the game. The film The Man Who Knew Infinity features a short sequence of G. H. Hardy (Jeremy Irons) and John Edensor Littlewood (Toby Jones) playing real tennis.

The series Billions, Opportunity Zone episode, very briefly features Damian Lewis and Harry Lennix playing real tennis.

In the movie Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead they play a game of questions in a disused real tennis court.

Televised matches[]

Real tennis has occasionally been televised, but the court (which does not well lend itself to the placement of cameras), the speed at which the ball travels, and the complexity of the rules all militate against the effectiveness and popularity of televised programming.

Web-streaming is proving a helpful innovation, and realtennis.tv broadcast its first tournament, the European Open, from 8–9 March 2011. There were three 'main events' shown; the two men's semi finals and the men's final. The final was between Bryn Sayers and Robert Fahey, with Fahey taking the title in four sets.

Many top national and international tournaments can be seen live or on replay via YouTube channels:

in the USA: United States Court Tennis Association

in the UK: T&RA Media

in France: Real Tennis France

Notable players[]

- Prince Edward, Earl of Wessex who notably played on 50 courts around the world in 2018 to support the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award.

- Joshua Crane: American champion from 1901 to 1905, Crane's career coincided with that of Jay Gould.[20][21]

- Pierre Etchebaster: World Champion, 1928–1953, d. 24 March 1980.[22]

- Claire Vigrass Fahey: Current Women's World Champion[23]

- Robert Fahey: World Champion, 1994–2016, 2018. Fahey successfully defended his world championship title more times (11) than any previous champion. In April 2018 he regained the title defeating Camden Riviere 7 sets to 5.[24]

- Jay Gould II: American champion from 1906 to 1926, one of the longest streaks in the history of sport. From 1907 to 1925, he lost only one singles match, to English champion . During that period, he never lost even a set to an amateur.[25]

- G. H. Hardy

- John Moyer Heathcote

- King Henry VIII of England

- Jeremy Howard, President and Chief Scientist of Kaggle, Co-Founder of Optimal Decision Group and Fastmail.fm

- King John III of Sweden

- Northrup R. Knox, multiple-time American champion. He retired undefeated.

- George Lambert

- King Louis X of France

- Penny Fellows Lumley, multiple singles and doubles champion in British, US, French and Australian Opens. Grand Slam 1996–97. Now Ladies Masters Champion.[23][26]

- Hon. Alfred Lyttelton

- Julian Marshall

- Eustace Miles: The first foreign winner of the American championship in 1900. Unusually for the period, Miles was a vegetarian, and produced a book on dietetics entitled Muscle, Brain and Diet.[27]

- Tom Pettitt

- Camden Riviere: 2016 World Champion

- Chris Ronaldson: World Champion, 1981–1987[28][29][30]

- John Rowan – World Interbank Challenge Champion[citation needed]

- Richard D. Sears: First American amateur champion of court tennis in 1892, and apparent inventor of the overhead "railroad service," currently the most popular serve in the game.[31]

- Fred Tompkins: Head professional of the Philadelphia court. When the New York Racquet and Tennis club opened, Fred Tompkins was invited to be head professional. However, when Fred went to his brother Alfred to borrow money for his passage, Alfred decided to go over in Fred's place; Fred Tompkins later took over the Philadelphia court instead.[32]

- Sarah Vigrass: Two-time World Doubles Champion (with her sister; Claire)[23]

- Pierre Cipriano: US National Team member, 3x consecutive Tuxedo Gold Racquet winner and inventor of the ‘Viper’ serve, an automatic way of winning a point when the server stands at Second Gallery and hits the ball as hard as he can directly at (and hopefully striking) his opponent who is set to receive.

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Schickel, Richard (1975). The World of Tennis. New York: Random House. p. 32. ISBN 0-394-49940-9.

- ^ The Macquarie Dictionary

- ^ https://www.thecourier.com.au/story/5312518/prince-edward-to-play-real-tennis-during-ballarat-visit/

- ^ "An introduction to the rules of Real Tennis". Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ "What is Real Tennis?". Holyport Real Tennis Club. Retrieved 2019-05-17.

- ^ Max Robertson, The Encyclopedia of Tennis, New York, The Viking Press, ISBN 978-0-670-29408-4, p.17

- ^ "Factsheet – Real Tennis and The Royal Tennis Court at Hampton Court Palace" (PDF). www.hrp.org.uk. Historic Royal Palaces. Archived from the original (pdf) on 2015-09-24.

- ^ The Encyclopedia of Tennis, p. 18

- ^ The Encyclopedia of Tennis, p. 17

- ^ The Encyclopedia of Tennis, p. 21

- ^ John Astley (1885), The Monumental Inscriptions in the Parish Church of S. Michael, Coventry, together with drawings of all the arms found therein, p. 21, Wikidata Q98360469

- ^ https://content.historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/played-in-london-directory-sporting-assets-london/DirectoryofHistoricSportingAssetsinLondon.pdf/ Section 4.19 p. 66 [accessed 24 October 2016]

- ^ Millar, William (2016). Plastering: Plain and Decorative. London: Routledge. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-873394-30-4.

- ^ Played in Britain for English Heritage (2014). "Played in London:A directory of historic sporting assets in London, 14.16 Hammersmith and Fulham". p. 66. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- ^ "Heritage Explorer – Result Detail". www.heritage-explorer.co.uk.

- ^ "Court Register". realtennissociety.org. 12 October 2013.

- ^ Dictionary of Scottish Architects http://www.scottisharchitects.org.uk/architect_full.php?id=204796 [accessed 24 October 2016] Note: The death date listed for Joseph Bickley in the dictionary is inaccurate.

- ^ Jesmond Dene Real Tennis Club – History

- ^ de Bondt, C (1993) Heeft yemant lust met bal, of met reket te spelen...? Hilversum: Verloren, ISBN 978-90-6550-379-4.

- ^ "Joshua Crane, sportsman, dies". The New York Times. 8 December 1964. Archived from the original on 11 January 2018.

- ^ Danzig p. 58.

- ^ "Pierre Etchebaster". International Tennis Hall of Fame. Retrieved 2016-07-17.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Current Top Players". www.lrta.org.uk. Retrieved 2018-03-31.

- ^ "Historical Results". www.irtpa.com. Retrieved 2018-03-31.

- ^ Danzig pp. 60–66"

- ^ "Past Champions". www.lrta.org.uk. Retrieved 2018-03-31.

- ^ Danzig. pp. 56–57.

- ^ "Historical Results". www.irtpa.com. Retrieved 2017-09-25.

- ^ magazine, Robert W. Stock; Robert W. Stock is a senior editor on the staff of this (1983-03-06). "THE COURTLIEST TENNIS GAME OF THEM ALL". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-09-25.

- ^ "Real Tennis | Radley College". www.radley.org.uk. Retrieved 2017-09-25.

- ^ Allison Danzig, The Racquet Game (MacMillan 1930) p. 54

- ^ Danzig p. 50.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jeu de paume. |

| Wikiversity has learning resources about Games of gain-ground/Real tennis |

- Article "Tennis" in the 1797 edition of Encyclopedia Britannica

- The Real Tennis Society

- Real tennis in Jesmond, article at BBC Tyne

- Photos of real tennis court in Jesmond, from BBC Tyne

- A History of Tennis

- An interactive map of all 50+ remaining courts worldwide

- "It Takes a $100,000 Court like This to Play Court Tennis," Life, March 1, 1937, pp. 28–31. (Text and pictures of the court at Manhattan's Racquet and Tennis Club)

- Historic Real Tennis Court in the Casino Building on the campus of Georgian Court University, Lakewood, NJ

- Official site of the French Courte Paume Comité (Real tennis in french) (in French)

- Real tennis

- Forms of tennis

- Sport in Hammersmith and Fulham

- Ball games

- Racquet sports