Reichsgau Wallonien

| Reichsgau Wallonien Gau Du Reich Wallonie | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reichsgau of Nazi Germany | |||||||||||

| 1944–1945 | |||||||||||

Flag

Coat of arms

| |||||||||||

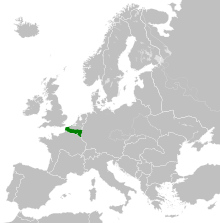

The de jure borders of Reichsgau Wallonien within Nazi Germany in 1945 | |||||||||||

| Capital | Liège (claimed as capital) | ||||||||||

| Government | |||||||||||

| Gauleiter | |||||||||||

• 1944–1945 | Léon Degrelle | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Established | 15 December 1944 | ||||||||||

• German surrender | January 1945 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

The Reichsgau Wallonia (German: Reichsgau Wallonien; French: Gau du Reich Wallonie) was a short-lived Reichsgau of Nazi Germany established in 1944. It encompassed present-day Wallonia in its old provincial borders, excluding Comines-Warneton but including Voeren. Eupen-Malmedy and Moresnet were also omitted, both of which had already been incorporated into Germany after its victory in the Battle of France in 1940.

When Nazi Germany annexed the Reichskommissariat of Belgium and Northern France on 15 December 1944, no part of the planned Reichsgau Wallonia was under German control. During the Battle of the Bulge, all territory east of the Western Front within Belgium (excluding Bastogne) became part of the Reichsgau Wallonia. The most populous municipality held by the Germans within the Reichsgau Wallonia was Rochefort.

History[]

After its invasion by Germany in June 1940, Belgium was initially placed under a "temporary" military government, in spite of more radical factions within the German government such as the SS urging for the installation of another Nazi civil government as had been done in Norway and the Netherlands.[1] It was joined together with the two French départements of Nord and Pas-de-Calais (included on the grounds that part of this territory belonged to Germanic Flanders, as well as the fact that the entire region formed an integral economic unit[2]) as the Military Administration in Belgium and North France (Militärverwaltung in Belgien und Nordfrankreich).

In spite of this uncompromising attitude at the time, it was decided that the entire area should someday be assimilated into the Third Reich[3] and divided into three new Reichsgaue of the Greater Germanic Reich: Flandern and Brabant for the Flemish territories, and Wallonien for the Walloon parts.[4] On 12 July 1944, a Reichskommissariat Belgien-Nordfrankreich was established to accomplish precisely this goal, derived from the previous military administration.[5] This step was curiously only taken at the very end of World War II, when Germany's armies were already in full retreat. The new government was already ousted by the Allied advances in Western Europe in September 1944, and the authority of the Belgian government-in-exile was restored. The actual incorporation into the Nazi state of these new provinces therefore only occurred de jure and with its leaders already in exile in Germany. The only place where any notable gain was made in re-establishing Reich authority occurred in parts of southern Wallonia during the Ardennes Campaign. The collaborators merely achieved a Pyrrhic victory since when the Allied tanks had rolled into Belgium several months before, this already signalled the end of their personal domains in the Reich. Many of their supporters fled to Germany where they were conscripted into the Waffen-SS to participate in the final military campaigns of the Third Reich.

In December 1944, Belgium (theoretically including the two French departments) was split up into a Reichsgau Wallonien, a Reichsgau Flandern, and a Distrikt Brüssel, all of which were nominally annexed by the Greater German Reich (therefore excluding the proposed Brabant province).[6] In Wallonia, the Rexist Party under the leadership of Léon Degrelle became the sole political party, in Flanders, it was the DeVlag party under the leadership of Jef van de Wiele. Degrelle was appointed as "Leader of the Walloon people" (Chef-du-People Wallon, Volksführer der Wallonen in German), in addition to the usual titles of Gauleiter und Reichsstatthalter bestowed upon Nazi German regional administrators.

The Walloons, in spite of their French national and linguistic identity, were regarded as Romanized Germanics by the Nazis, and therefore as a racial kindred-people of the Germans.[7] After initially refusing entry to French and Walloon volunteers in the Waffen-SS for their perceived racial inferiority, Heinrich Himmler later changed his position, stating that he regarded the Walloon SS "as the renaissance movement of a fundamentally Germanic people (als die Erneuerungsbewegung eines in Kern germanischen Volkes)." Racial planners therefore proposed the Germanization and Batavianization of the Walloons and the integrated parts of northern France.

Even before the actual incorporation of all of Wallonia, the Germans also seriously considered annexing, in addition to Luxembourg, the small German-speaking (Lëtzebuergesh) area centered on Arlon to a "bordering region of the Reich", presumably under the civil administrator of Gau Koblenz-Trier (from 1942 Moselland).[8][9] In May and June 1940, the German occupiers also discussed annexing, "according to the principle of national traditions", the Low Dietsch-speaking region west of Eupen (so called Platdietse streek) centered on the town of Limbourg, which was the historic core of the Duchy of Limburg.[9]

See also[]

- Administrative divisions of Nazi Germany

- Areas annexed by Nazi Germany

- Greater Germanic Reich

Notes[]

- ^ Rich, Norman: Hitler's War Aims: The Establishment of the New Order, page 173. W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1974.

- ^ Rich, Norman, page 172.

- ^ Rich, Norman, pp. 171, 196.

- ^ , Rolf-Dieter Müller, (2003). Germany and the Second World War: Volume V/II. Oxford University Press, p. 26 [1]

- ^ Rich, Norman, p. 195.

- ^ Lipgens, Walter: Documents on the History of European integration: Volume 1 - Continental Plans for European Integration 1939-1945, page 45. Walter de Gruyter & Co., 1974.

- ^ Williams, John Frank (2005). Corporal Hitler and the Great War 1914-1918: the List Regiment. Frank Cass, p. 209 [2]

- ^ Gildea, Robert; Wieviorka, Olivier; Warring, Anette: Surviving Hitler and Mussolini: daily life in occupied Europe, page 130. Berg, 2006. [3]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Werner Hamacher,Neil Hertz,Thomas Keenan: Responses: on Paul de Man's Wartime journalism. U of Nebraska Press, 1989, p. 444 [4]

- States and territories established in 1944

- States and territories disestablished in 1945

- German occupation of Belgium during World War II

- 1944 establishments in Belgium

- 1945 disestablishments in Belgium