Roman von Ungern-Sternberg

Roman von Ungern-Sternberg | |

|---|---|

Roman Fyodorovich Ungern-Sternberg in Irkutsk under interrogation at the headquarters of the 5th Red Army[a] | |

| Birth name | Nikolai Robert Maximilian Freiherr[b] von Ungern-Sternberg |

| Nickname(s) |

|

| Born | 10 January 1886 Graz, Styria, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | 15 September 1921 (aged 35) Novosibirsk, Russian SFSR |

| Allegiance |

|

| Branch | |

| Years of service | 1906–1921 |

| Rank | Lieutenant general |

| Commands held | Asiatic Cavalry Division |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards |

|

| Spouse(s) | Elena Pavlovna "Ji"

(m. 1919; div. 1920) |

Baron Roman Fyodorovich von Ungern-Sternberg (born Nikolai Robert Maximilian Freiherr[b] von Ungern-Sternberg; Russian: Рома́н Фёдорович фон У́нгерн-Ште́рнберг, romanized: Román Fëdorovič fon Úngern-Štérnberg;[1] 10 January 1886 – 15 September 1921), often referred to as Baron Ungern, was an anticommunist general in the Russian Civil War and then an independent warlord who intervened in Mongolia against China. A part of the Russian Empire's Baltic German minority, Ungern was an ultraconservative monarchist who aspired to restore the Russian monarchy after the 1917 Russian Revolutions and to revive the Mongol Empire under the rule of the Bogd Khan. His attraction to Vajrayana Buddhism and his eccentric, often violent, treatment of enemies and his own men earned him the sobriquet "the Mad Baron" or "the Bloody Baron".

In February 1921, at the head of the Asiatic Cavalry Division, Ungern expelled Chinese troops from Mongolia and restored the monarchic power of the Bogd Khan. During his five-month occupation of Outer Mongolia, Ungern imposed order on the capital city, Ikh Khüree (now Ulaanbaatar), by fear, intimidation and brutal violence against his opponents, particularly the Bolsheviks. In June 1921, he travelled to eastern Siberia to support anti-Bolshevik partisan forces and to head off a joint Red Army-Mongolian rebel invasion. That action ultimately led to his defeat and capture two months later. He was taken prisoner by the Red Army and, a month later, was put on trial for "counter-revolution" in Novonikolaevsk. After a six-hour show trial, he was found guilty and on 15 September 1921 he was executed.

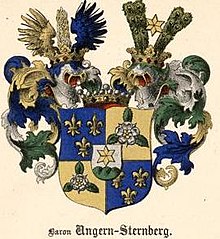

Early life[]

Nikolai Robert Maximilian Freiherr von Ungern-Sternberg was born in Graz, Austria, on 10 January 1886 [O.S. 29 December 1885] to a noble Baltic German family. The Ungern-Sternberg family had settled in present-day Estonia during the Middle Ages.[2] Ungern-Sternberg's first language was German, but he became fluent in French, Russian, English and Estonian.[3] His mother was a German noblewoman, Sophie Charlotte von Wimpffen, later Sophie Charlotte von Ungern-Sternberg, and his father was Theodor Leonhard Rudolph Freiherr von Ungern-Sternberg (1857–1918). He also had Hungarian roots and claimed descent from Batu Khan, Genghis Khan's grandson, which played a role in his dream of reviving the Mongol Empire.[4]

In 1888 his family moved to Reval (Tallinn), the capital of the Governorate of Estonia in the Russian Empire, where his parents divorced in 1891. In 1894 his mother married the Baltic-German nobleman Oskar Anselm Hermann Freiherr von Hoyningen-Huene.[5] Ungern-Sternberg grew up in the Governorate, with his home being the Hoyningen-Huene estate at Jerwakant (modern Järvakandi, Estonia), deep in the forests, about 65 kilometres (40 miles) from Reval.[6] In the summer, Ungern-Sternberg lived on the Baltic island of Dagö (now Hiiumaa), which he liked to boast had belonged to his family for over 200 years.[7]

As a boy, Ungern-Sternberg was noted for being such a ferocious bully that even the other bullies feared him and several parents forbade their children from playing with him as he was a "terror".[7] Ungern was well known for his love of torturing animals, and at the age of 12 he tried to strangle to death his cousin's pet owl for no particularly good reason other than his cruelty towards animals.[7] Ungern-Sternberg had extreme pride in his ancient, aristocratic family and later wrote that his family had over the centuries "never taken orders from the working classes" and it was outrageous that "dirty workers who've never had any servants of their own, but still think they can command" should have any say in the ruling of the vast Russian Empire.[8] Ungern-Sternberg, although proud of his German origin, identified himself very strongly with the Russian Empire. When asked whether his "family had distinguished itself in Russian service", Ungern proudly answered: "Seventy-two killed in wartime!"[9] Ungern-Sternberg believed that return to monarchies in Europe was possible with the aid of "cavalry people" – meaning Russian Cossacks, Buryats, Tatars, Mongols, Kyrgyz, Kalmyks, etc.[10]

In 1893 Ungern-Sternberg surveyed mountain ranges for the Tiflis Geographical Society in Tbilisi. In 1898, his father was briefly imprisoned for fraud and, in 1899, was committed to the local insane asylum.[11] From 1900 to 1902 Ungern attended the Nicholas I Gymnasium in Reval. His school records show that he was an unruly, bad-tempered young man who was constantly in trouble with his teachers because of frequent fights with other cadets and breaking other school rules: smoking in bed, growing long hair, leaving without permission, etc., which finally led to the schoolmaster writing a letter in February 1905 to his stepfather and mother to ask them to withdraw him from the school or he would be expelled.[12] In 1905, he left the school to join the fighting in eastern Russia during the Russo-Japanese War, but it is unclear whether he participated in operations against the Japanese or if all military operations had ceased before his arrival in Manchuria,[13] although he was awarded the Russo-Japanese War Medal in 1913.[14]

In 1905, Russia exploded into revolution and Estonian peasants went on a bloody jacquerie against the Baltic-German nobility, which owned most of the land there. Aristocrats were lynched and their estates burned down,[15] one being the one at Jerwakant where Ungern-Sternberg had grown up. The Revolution of 1905 and the destruction of the Jerwakant estate were huge traumas to Ungern-Sternberg, who saw the jacquerie as confirming his belief that the Estonian peasants who worked on his family's lands were all "rough, untutored, wild and constantly angry, hating everybody and everything without understanding why".[16]

In 1906, Ungern was transferred to service in the Pavlovsk Military School, in St. Petersburg, as a cadet of ordinary rank.[17] As an army cadet, he proved to be a better student than he ever was as a naval cadet, and he actually studied his course material, but in the words of Palmer, he was a "mediocre student" at best.[18] During the same period, Ungern-Sternberg had become obsessed with the occult and was especially interested in Buddhism. His cousin Count Hermann von Keyserling, who later knew him well, wrote that the baron was very curious from his teenage years onward with "Tibetan and Hindu philosophy" and often spoke of the mystical powers possessed by "geometrical symbols". Keyserling called Ungern-Sternberg "one of the most metaphysically and occultly gifted men I have ever met" and believed that the baron was a clairvoyant, who could read the minds of the people around him.[19] Later, in Mongolia, Ungern became a Buddhist but did not leave the Lutheran faith. There is a widespread view that he was viewed by Mongols as the incarnation of the "God of War" (the figure of Jamsaran in Tibetan and Mongol folklore). Although many Mongols may have believed him to be a deity or at the very least a re-incarnation of Genghis Khan, Ungern was never officially proclaimed to be any of those incarnations.[20][page needed]

After graduating, he served as an officer in eastern Siberia in the 1st Argunsky and then in the 1st Amursky Cossack regiments, where he became enthralled with the lifestyle of nomadic peoples, such as the Mongols and Buryats. Ungern had specifically asked to be stationed with a Cossack regiment in Asia, as he wanted to learn more about Asian culture, a request that was granted.[21]

Ungern-Sternberg was notorious for his heavy drinking and exceptionally cantankerous moods. In one such brawl, his face was scarred when the officer that he fought struck him with his sword, leaving him with a distinctive facial scar.[11] It has been claimed that the sword blow that caused the scar also caused brain damage that was the root of his insanity.[22] However, a special study revealed that Ungern-Sternberg was not mentally insane, although the wound affected his irritability.[23]

Those who knew him well described him as very drawn towards "Eastern culture", as he was fascinated by Asian cultures, especially that of the Mongols and the Buryats.[24] At the same time, Ungern was an excellent horseman, who earned the respect of the Mongols and the Buryats because of his skill at riding and fighting from a horse and for being equally adept at using both a gun and his sword.[25]

In 1913, at his request, he transferred to the reserves. Ungern moved to Outer Mongolia to assist the Mongols in their struggle for independence from China, but Russian officials prevented him from fighting on the side of Mongolian troops. He arrived in the town of Khovd, in western Mongolia, and served as an out-of-staff officer in the Cossack guard detachment at the Russian consulate.[26]

First World War[]

On 19 July 1914, Ungern joined frontline forces as part of the second-turn 34th Regiment of Cossack troops stationed on the Austro-Hungarian frontier in Galicia. He took part in the Russian offensive in East Prussia. From 1915 to 1916, he also participated in rear-action raids on German troops by the L.N. Punin Cavalry Special Task Force.[27][page needed] Ungern served in the Nerchinsk Regiment.

Throughout the war on the Eastern Front, he gained a reputation as an extremely brave but somewhat reckless and mentally unstable officer, with no fear of death and seemed most happy leading cavalry charges or being in the thick of combat.[28] He was decorated with several military awards: orders of St. George of the 4th grade, St. Vladimir of the 4th grade, St. Anna of the 3rd and 4th grades and St. Stanislas of the 3rd grade. Despite his many awards, he was eventually discharged from one of his command positions for attacking another officer and a hall porter during a drunken rage in October 1916, which led to his being court-martialed and sentenced to two months in prison.[29] General Pyotr Wrangel mentions Ungern's determination in his memoirs.

After his release from prison in January 1917, Ungern was transferred to the Caucasian Theatre of the conflict, where Russia was fighting against the Ottoman Empire.[30] The February Revolution that ended the rule of the House of Romanov was an extremely bitter blow to the monarchist Ungern-Sternberg, who saw the revolution as the beginning of the end of Russia.[31] In the Caucasus, Ungern-Sternberg first met Cossack Captain Grigory Semyonov, who was later one of most well-known Russian anticommunist warlords in Siberia.

In April 1917, near Urmia, Iran, Ungern, together with Semyonov, started to organise a volunteer military unit of local Assyrian Christians. The Ottoman government had waged the Assyrian genocide in an attempt to exterminate the Assyrian minority, which led to thousands of Assyrians fleeing to the Russian lines.[32] Ungern and Semyonov conceived of a scheme under which the two would organise and lead Assyrian troops to serve as an example for the Russian army, which was being demoralised by the revolutionary mood.[29] Under his command, his Assyrians went on to score some minor victories over the Turks, but their total contribution to Russia's war effort was limited.[33] Afterwards, the Assyrian scheme led Semyonov to the idea of placing Buryat troops in Siberia. The Kerensky government gave its approval to Semyonov's plans, and Ungern-Sternberg soon headed east to join his friend in trying to raise a Buryat regiment.[34]

Russian Civil War[]

After the Bolshevik-led October Revolution in 1917, Semyonov and Ungern declared their allegiance to the Romanovs and vowed to fight the revolutionaries. In late 1917, Ungern, Semyonov and five Cossacks peacefully disarmed a group of about 1,500 pro-Red combatants on a railway station in Manchuria on the Far Eastern Railway (FER) in China, near the Russian border. For a time, the station in Manchuria was a stronghold of Semyonov and Ungern in their preparations for war in Transbaikal. They started to enrol troops in a Special Manchurian Regiment, which became a nucleus for anticommunist forces led by Semyonov.[35]

After the White troops defeated the Reds on a section of the FER line in Russia, Semyonov appointed Ungern commandant of troops stationed in Dauria, a railway station in a strategic position east-southeast of Lake Baikal. Semyonov and Ungern, though fervently anti-Bolshevik, were not typical of the figures to be found in the leadership of the White movement, as their plans differed from those of the main White leaders. Semyonov refused to recognize the authority of Admiral Alexander Kolchak, the nominal leader of the Whites in Siberia. Instead, he acted independently and was supported by the Japanese with arms and money.

For White leaders like Kolchak and Denikin, who believed in a "Russia strong and indivisible", that represented high treason. Ungern was nominally subordinated to Semyonov but also often acted independently.[36] Kolchak was a conservative but not a monarchist, and he promised that after the victory of the Whites he would reconvene the Constituent Assembly, disbanded by the Bolsheviks in January 1918, which would then decide the future of Russia, including the question of whether or not to restore the monarchy.[37] Ungern, to the contrary, believed that monarchs were accountable only to God, and the monarchy was the political system that God had chosen for Russia and so it was self-evident that it should be restored to the way it had existed before the October Manifesto of 1905. For Ungern, the opinions of the people of Russia were irrelevant, as monarchs were not accountable to the people.[citation needed]

Because of his successful military operations in Hailar and Dauria, Ungern received the rank of major-general. Semyonov entrusted him with forming military units to battle Bolshevik forces. They enrolled Buryats and Mongols in their national military units.

In Dauria, Ungern formed the volunteer Asiatic Cavalry Division. Ungern reinforced his military station at Dauria, creating a kind of fortress from which his troops launched attacks on Red forces. Under his rule, Dauria became a well-known "torture centre" filled with the bones of dozens of Ungern's victims, who were executed because of accusations of being Reds or thieves (details in [38]). Ungern's chief executioner had been a Colonel Laurentz, but in Mongolia, Ungern had him executed because he lost Ungern's trust under unclear circumstances.[39]

Like many other White units, Ungern's troops used "requisitions" as a source of their supply. They examined trains passing through Dauria to Manchuria. The confiscations did not significantly diminish the supplies of Kolchak's forces, but private Russian and Chinese merchants lost considerable property.[40]

In 1919, taking advantage of the weakness of Russia's government caused by revolutions and civil war, the Chinese government, established by members of the Anhui military party, sent troops, led by General Xu Shuzheng, to join Outer Mongolia to China and end its autonomy, which violated the terms of a tripartite Russian-Mongolian-Chinese agreement concluded in 1915 that secured the autonomy of Outer Mongolia and did not allow the presence of Chinese troops except for small numbers of consular guards.[41] Although the Anhui party was supported by Japan, indications of Japan-inspired Chinese occupation of Outer Mongolia[42] have not yet been confirmed by documents.[43]

After the fall of Anhui party rule in China, Chinese soldiers in Mongolia found themselves effectively abandoned. They rebelled against their commanders and plundered and killed Mongols and foreigners.[44][page needed] Some of the Chinese troops during the occupation were Tsahar (Chahar) Mongols from Inner Mongolia, who had been a major cause of animosity between Outer Mongols (Khalkhas) and Inner Mongols.[45]

As part of his plans, Ungern travelled to Manchuria and China (February to September 1919), where he established contacts with monarchist circles and also made preparations for Semyonov to meet the Manchurian warlord Marshal Zhang Zuolin, the "Old Marshal". In July 1919, Ungern married the Manchurian princess Ji in an Orthodox ceremony in Harbin. The princess was given the name Elena Pavlovna. She and Ungern communicated in English, their only common language.[46] The marriage had a political aim, as Ji was a princess and a relative of General Zhang Kuiwu, the commander of Chinese troops at the western end of the Chinese-Manchurian Railway and the governor of Hailar.[36]

Restoration of independence of Outer Mongolia[]

After Kolchak's defeat at the hands of the Red Army and the subsequent decision of Japan to withdraw its expeditionary troops from the Transbaikal, Semyonov, unable to withstand the pressure of Bolshevik forces, planned a retreat to Manchuria.

Ungern, however, saw it as an opportunity to implement his monarchist plan. On 7 August 1920, he broke his allegiance to Semyonov and transformed his Asiatic Cavalry Division into a guerrilla detachment.[20][page needed] Ungern's troops started to move towards the border of Outer Mongolia, crossed the northern border of Outer Mongolia on 1 October 1920 and moved southwest.[47][page needed] Having crossed the Mongolian border, Ungern moved westwards to the Mongolian capital of Urga (officially Niislel Khuree, now Ulaanbaatar), where he entered into negotiations with Chinese occupying forces. All of his demands, including the disarmament of the Chinese troops, were rejected.

On 26–27 October and again on 2–4 November 1920, Ungern's troops assaulted Urga but suffered disastrous losses. After the defeat, his forces retreated to the upper currents of the Kherlen River, in Setsen-Khan Aimag, a district ruled by princes with the title Setsen Khan, in eastern Outer Mongolia. He was supported by Mongols who sought independence from Chinese occupation, especially the spiritual and secular leader of Mongols, the Bogd Khan, who secretly sent Ungern his blessing for expelling Chinese from Mongolia.

The Chinese had tightened their control of Outer Mongolia by then by strictly regulating Buddhist services in monasteries and imprisoning Russians and Mongols, whom they considered "separatists". According to the memoirs of M. G. Tornovsky, the Asiatic Division numbered 1,460 men, while the Chinese garrison was 7000 strong. The Chinese had the advantage in artillery and machine guns and had built a network of trenches in and around Urga.[47][page needed] At his camp, Ungern imposed ferocious[neutrality is disputed] discipline on his Russian soldiers to prevent desertion and demoralisation.[citation needed]

Ungern's troops began moving from their camp to Urga on 31 January. On 2 February, they battled for control of Chinese front lines and secured parts of Urga.[47][page needed] His detachment, led by B. P. Rezukhin, captured Chinese front-line fortifications near Small Madachan and Big Madachan settlements in the southeastern vicinities of Urga. During the battle Ungern's special detachment of Tibetans, Mongols, Buryats, and Russians rescued the Bogd Khan from house arrest and transported him through the Bogd Uul to Manjushri Monastery. At the same time, another detachment moved to the mountains east of Urga.[48]

On 3 February, he gave his soldiers a respite. Borrowing a tactic from Genghis Khan, he ordered his troops to light a large number of campfires in the hills surrounding Urga and to use them as reference points for Rezukhin's detachment. That made the town appear to be surrounded by an overwhelming force.[44][page needed]

Early on 4 February, Ungern launched an assault on the Chinese White barracks from the east, captured them and divided his forces into two parts. The first launched a major assault on the remaining Chinese positions in the Chinese trade settlement (Chinese: 買賣城, Maimaicheng). The second moved westwards towards the Consular Settlement. Upon reaching the Maimaicheng, Ungern had his men smash their way in by blasting the gates with explosives and improvised battering rams.[49] After breaking in, a general slaughter set in, as both sides fought with sabres.

After the capture of Maimacheng, Ungern joined his troops attacking Chinese troops at the Consular Settlement. After a Chinese counterattack, Ungern's soldiers retreated a short distance northeast and then launched another attack with the support of another Cossack and Mongolian detachment, which began an attack from the northeast and northwest. Ungern's troops gradually moved westwards in Urga, pursuing retreating Chinese soldiers.

The capital city was finally taken on the evening of 4 February. Chinese civilian administrators and military commanders abandoned their soldiers and fled northwards from Urga in 11 cars in the night of 3–4 February. Chinese troops fled northward on 4 and 5 February. They massacred any Mongolian civilians they encountered along the road from Urga to the Russian border.

Russian settlers who supported the Reds moved from Urga, together with the fleeing Chinese troops. During the capture of Urga, the Chinese lost about 1500 men, and Ungern's forces suffered about 60 casualties.[50]

After the battle, Ungern's troops began plundering Chinese stores and killing Russian Jews who were living in Urga, as the Cossacks had also been set against the Jews. Ungern himself ordered the Jews to be killed except for those who had notes from him sparing their lives. It has been estimated by surviving archival documents and memoirs that 43–50 Jews were killed during Ungern's stay in Mongolia, about 5%–6% of all those executed under his orders. Several days later, the looting by his troops was stopped by Ungern, but his secret police bureau, led by Colonel Leonid Sipailo, continued searching for "Reds".[51] Between 11 and 13 March, Ungern captured a fortified Chinese base at Choir, between the Otsol Uul and Choiryn Bogd Uul Mountains, south of Urga. Ungern had 900 troops and the Chinese defenders about 1500. After capturing Choir, Ungern returned to Urga. His detachments, consisting of Cossacks and Mongols, moved southward to Zamyn-Üüd, a frontier settlement and another Chinese base. The defending Chinese soldiers abandoned Zamyn-Üüd without a fight.[47][page needed][52]

When the remaining Chinese troops, having retreated to northern Mongolia near Kyakhta, attempted to go around Urga to the west to reach China, the Russians and the Mongols feared that they were attempting to recapture Urga. Several hundred Cossack and Mongol troops were dispatched to stop the Chinese forces, which numbered several thousand, in the area of Talyn Ulaankhad Hill near the Urga–Uliastai road in central Mongolia. After a battle that raged from 30 March to 2 April in which more than 1000 Chinese and approximately 100 Mongols, Russians and Buryats were killed, the Chinese were routed and chased to the southern border of the country. Thus Chinese forces left Outer Mongolia.[53][54]

Mongolia and Ungern (February to August 1921)[]

Ungern, Mongolian lamas and princes brought the Bogd Khan from Manjusri Monastery to Urga on 21 February 1921. On 22 February, a solemn ceremony took place to restore the Bogd Khan to the throne.[55][56] As a reward for ousting the Chinese from Urga, the Bogd Khan granted Ungern the high hereditary title darkhan khoshoi chin wang in the degree of khan, and other privileges. Other officers, lamas and princes who had participated in these events also received high titles and awards.[57][58] For seizing Urga, Ungern received from Semyonov the rank of lieutenant-general.[citation needed]

On 22 February 1921, Mongolia was proclaimed an independent monarchy. Supreme power over Mongolia belonged to the Bogd Khan, or the 8th Bogd Gegen Jebtsundamba Khutuktu.[20][page needed] According to some eyewitnesses (such as his engineer and officer Kamil Giżycki, and Polish adventurer and writer Ferdynand Antoni Ossendowski), Ungern was the first to institute order in Urga by imposing street cleaning and sanitation, promoting religious life and tolerance in the capital and attempting to reform the economy.

Ossendowski, one of the most popular Polish writers in his lifetime (at the time of his death in 1945, his overseas sales were the second-highest of all the writers of Poland), had served as an official in Kolchak's government and, after its collapse, fled to Mongolia.[59] He became one of Ungern's very few friends, and in 1922, published a best-selling book in English, Beasts, Men and Gods, about his adventures in Siberia and Mongolia, which remains the book by which the Ungern story is best known in the English-speaking world.[60] Comparison of Ossendowski's diary with his book and documents on Mongolia revealed that his reports on Mongolia at Ungern are largely true, except for a few stories. Ossendowski was the first to describe Ungern's views in terms of Theosophy, but Ungern himself had never been a Theosophist.[61]

Ungern did not interfere in Mongolian affairs and assisted Mongols only in some issues according to orders of the Bogd Khan. Russian colonists, on the other hand, suffered cruelties from Ungern's secret police bureau led by Leonid Sipailo. Many innocent people were tortured and killed by Sipailo and his subordinates. A list of people known to have been killed on Ungern's orders or by others on their pretext, both in Russia and Mongolia, confirms the deaths of 846 people, approximately 100–120 from Urga, which was about 3%–8% of the total foreign colony population.[62]

Some eyewitnesses considered his Asiatic Cavalry Division as a base for a future Mongolian national army. The division consisted of national detachments, such as the Chinese regiment, Japanese unit, various Cossack regiments, Mongol, Buryat, Tatar and other peoples' units. Ungern said that 16 nationalities served in his division.

Dozens of Tibetans also served as part of his troops. They might have been sent by 13th Dalai Lama, with whom Ungern communicated, or the Tibetans may have belonged to the Tibetan colony in Urga.[20][page needed]

The presence of the Japanese unit in the division is often explained as evidence that Japan stood behind Ungern in his actions in Mongolia. Studies of their interrogations from Japanese archives revealed that they were mercenaries serving on their own, like other nationals in the division, and that Ungern was not managed by Japan.[63]

Defeat, capture and execution[]

The Bolsheviks started infiltrating Mongolia shortly after the October Revolution, long before they took control of the Russian Transbaikal. In 1921, various Red Army units belonging to Soviet Russia and to the Far Eastern Republic invaded the newly independent Mongolia to defeat Ungern. The forces included the Red Mongolian leader Damdin Sükhbaatar.

Spies and various smaller diversionary units went ahead to spread terror to weaken Ungern's forces. Ungern organised an expedition to meet these forces in Siberia and to support ongoing anti-Bolshevik rebellions. Believing that he had the unwavering popular support of locals in Siberia and Mongolia, Ungern failed to strengthen his troops properly, although he was vastly outnumbered and outgunned by the Red forces. However, he did not know that the Reds had successfully crushed uprisings in Siberia and that Soviet economic policies had temporarily softened in Lenin's New Economic Policy. Upon Ungern's arrival in Siberia, few local peasants and Cossacks volunteered to join him.[citation needed]

In the spring, the Asiatic Cavalry Division was divided into two brigades: one under the command of Lieutenant General Ungern and the second under Major General Rezukhin. In May, Rezukhin's brigade launched a raid beyond the Russian border, west of the Selenga River. Ungern's brigade left Urga and slowly moved to the Russian town of Troitskosavsk (present-day Kyakhta in Buryatia).

Meanwhile, the Reds moved large numbers of troops towards Mongolia from different directions. They had a tremendous advantage in equipment (armoured cars, aeroplanes, rail, gunboats, ammunition, human reserves etc.) and the number of troops. As a result, Ungern was defeated in battles that took place between 11 and 13 June, and he failed to capture Troitskosavsk. Combined Bolshevik and Red Mongol forces entered Urga on 6 July 1921 after a few small skirmishes with Ungern's guard detachments.[20][page needed]

Although they had captured Urga, the Red forces failed to defeat the main forces of the Asiatic Division (Ungern's and Rezukhin's brigades). Ungern regrouped and attempted to invade Transbaikal, across the Russo-Mongolian border. To rally his soldiers and local people, he quoted an agreement with Semyonov and pointed to a supposed Japanese offensive that was to support their drive, but neither Semyonov nor the Japanese were eager to assist him.

After several days of rest, the Asiatic Division started its raid into Soviet territory on 18 July. The eyewitnesses Kamil Giżycki and Mikhail Tornovsky gave similar estimates of their numbers: about 3000 men in total.[64][page needed] Ungern's troops penetrated deep into Russian territory.

The Soviets declared martial law in areas where the Whites were expected, including Verkhneudinsk (now Ulan-Ude, the capital of Buryatia). Ungern's troops captured many settlements, the northernmost being Novoselenginsk, which they occupied on 1 August. By then, Ungern had understood that his offensive was ill-prepared, and he had heard about the approach of large Red forces. On 2 August 1921, he began his retreat to Mongolia, where he declared his determination to fight communism.

While Ungern's troops wanted to abandon the war effort, head towards Manchuria and join with other Russian émigrés, it soon became clear that Ungern had other ideas. He wanted to retreat to Tuva and then to Tibet. Troops under both Ungern and Rezukhin effectively mutinied and hatched plots to kill their respective commanders.

On 17 August, Rezukhin was murdered. A day later, conspirators attempted to assassinate Ungern. His command then collapsed as his brigade broke apart. On 20 August, Ungern was captured by a Soviet detachment, led by guerrilla commander Petr Efimovich Shchetinkin, who was later a member of the Cheka.[65][page range too broad] After a show trial of 6 hours and 15 minutes on 15 September 1921, prosecuted by Yemelyan Yaroslavsky, Ungern was sentenced to execution by firing squad. The sentence was carried out that night in Novonikolaevsk (now Novosibirsk).[66]

When the news on the Baron's execution reached the Living Buddha [the Bogd Khan], he ordered services to be held in temples throughout Mongolia.[67]

In popular culture[]

- Ungern-Sternberg is the main villain in the video game Iron Storm.[68]

- In 1938, Ungern-Sternberg was the protagonist of a novel published in Germany, Ich befehle! Kampf und Tragödie des Barons Ungern-Sternberg (I Order! The Struggle and Tragedy of Baron Ungern-Sternberg) by , which often glossed over his more brutal tactics in order to paint him in the best light.[69]

- "Ungern-Sternberg" is a song by the French punk rock group , which contains the lyrics "Ungern-Sternberg, chevalier romantique / Tu attends la mort comme un amant sa promise" ("Ungern-Sternberg, romantic knight / You wait for death like a lover [waits] for his fiancée").[70]

- Ungern-Sternberg is often mentioned in the novels of the Spanish thriller writer Arturo Pérez-Reverte.[68]

- Ungern-Sternberg is featured in the graphic novel Corte Sconta detta Arcana by the Italian writer Hugo Pratt.[68]

- The novels of the Russian surrealist writer Victor Pelevin often feature Ungern-Sternberg, most notably his 1996 novel Chapayev and Void.[68]

See also[]

Further reading[]

- Ossendowski, Ferdynand (1922) Beasts, Men and Gods. New York.

- Kamil Giżycki (1929). Przez Urjanchaj i Mongolje. Lwow – Warszawa: wyd. Zakladu Nar. im. Ossolinskich.

- Alioshin, Dmitri. Asian Odyssey. H. Holt and Company, New York (1940), Cassell and Company Ltd, London (1941)

- Keyserling, Graf von, "Reise durch die Zeit-Abenteuer der Seele", vol. II (1948 (reprinted Buenos Aires, 1951)

- Krauthoff, Berndt. "Ich befehle! Kampf und Tragödie des Barons Ungern-Sternberg." (Strife and Glory in English) — Bremen: Carl Schünemann, 1938.

- Pozner, Vladimir (1938) Bloody Baron: the Story of Ungern–Sternberg. New York.

- Maclean, Fitzroy.(1975). To the Back of Beyond: An Illustrated Companion to Central Asia and Mongolia . Little, Brown & Co., Boston.

- Michalowski W. St. (1977). Testament Barona. Warsaw: Ludowa Spoldzielnia Wyd.

- Hopkirk, Peter (1986) Setting the East Ablaze: on Secret Service in Bolshevik Asia. Don Mills, Ont.

- Quenoy, Paul du. “Warlordism à la russe: Baron von Ungern-Sternberg’s Anti-Bolshevik Crusade, 1917–1921,” Revolutionary Russia, 16: 2, December 2003

- Quenoy, Paul du. “Perfecting the Show Trial: The Case of Baron von Ungern-Sternberg,” Revolutionary Russia, 19: 1, June 2006.

- Bodisco, Theophile von. Baron Ungern von Sternberg – der letzte Kriegsgott. Straelen Regin-Verl (2006)

- Palmer, James. (2009) The Bloody White Baron: The Extraordinary Story Of The Russian Nobleman Who Became The Last Khan Of Mongolia

- Yuzefovich, Leonid. Le baron Ungern, khan des steppes 2018, Paris, Horsemen of the Sands, Archipelago, 2018

- Znamenski, Andrei (2011) Red Shambhala: Magic, Prophecy, and Geopolitics in the Heart of Asia. Wheaton, IL: Quest Books. ISBN 978-0-8356-0891-6

- Kuzmin, S. L. 2016. Theocratic Statehood and the Buddhist Church in Mongolia in the Beginning of the 20th Century. Moscow: KMK Sci. Press, ISBN 978-5-9907838-0-5.

- Ribo, N. M. [Ryabukhin, N.M.] n.d. The Story of Baron Ungern Told by His Staff Physician. Hoover Institution, Stanford University, CSUZXX697-A.

Notes[]

- ^ Lieutenant General Baron Roman Fedorovich von Ungern-Sternberg in Irkutsk during interrogation at the headquarters of the 5th Soviet Army. September 1–2, 1921, attention not in Mongolia

- ^ Jump up to: a b Regarding personal names: Freiherr is a former title (translated as Baron). In Germany since 1919, it forms part of family names. The feminine forms are Freifrau and Freiin.

References[]

Citations[]

- ^ Kuzmin 2011, p. [page needed].

- ^ Palmer 2008, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Palmer 2008, p. 18.

- ^ Romein, Jan (1962). The Asian Century: A History of Modern Nationalism in Asia. Translated by Clark, R. T. Allen & Unwin. p. 128. ISBN 978-0049500082.

- ^ Kuzmin 2011, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Palmer 2008, p. 17.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Palmer 2008, p. 19.

- ^ Palmer 2008, p. 24.

- ^ Palmer 2008, p. 16.

- ^ Kuzmin 2011, p. 392.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Smith 1980, p. 591.

- ^ Palmer 2008, p. 20.

- ^ Tornovsky 2004a, p. 190.

- ^ Kuzmin 2013, p. 178.

- ^ Palmer 2008, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Palmer 2008, p. 25.

- ^ Kuzmin 2011, pp. 27–30.

- ^ Palmer 2008, p. 26.

- ^ Palmer 2008, p. 28.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Kuzmin 2011.

- ^ Palmer 2008, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Palmer 2008, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Kuzmin 2011, pp. 368–369.

- ^ Sunderland 2014, p. 57.

- ^ Palmer 2008, p. 37.

- ^ Kuzmin 2011, pp. 61–63.

- ^ Khoroshilova, O. Voiskovye Partizany Velikoi Voiny. St. Petersburg: Evropeiskii Dom Publ.

- ^ Smith 1980, p. 592.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kuzmin 2011, pp. 67–70.

- ^ Palmer 2008, p. 75.

- ^ Palmer 2008, p. 79.

- ^ Palmer 2008, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Ataman Semenov. O sebe. Vospominaniya, Mysli i Vyvody. Moscow: AST Publ., 2002

- ^ Palmer 2008, pp. 78–81.

- ^ Kuzmin 2011, pp. 76–78.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kuzmin 2011, pp. 94–96.

- ^ Palmer 2008, p. 87.

- ^ Kuzmin 2011, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Kuzmin 2011, p. 370.

- ^ Kuzmin 2011, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Kuzmin 2011, pp. 141–143.

- ^ Major, John S. (1990). The land and people of Mongolia. Harper and Row. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-397-32386-9.

- ^ Kuzmin 2011, pp. 120–55.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pershin 1999.

- ^ Bulag, Uradyn Erden (1998). Nationalism and Hybridity in Mongolia (illustrated ed.). Clarendon Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-0198233572. Archived from the original on 21 February 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- ^ Palmer 2008, p. 110.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Tornovsky 2004a.

- ^ Kuzmin 2011, pp. 176–178, 339–341.

- ^ Palmer, James The Bloody White Baron: The Extraordinary Story of the Russian Nobleman Who Became the Last Khan of Mongolia, New York: Basic Books, 2009, p. 154.

- ^ Kuzmin 2011, p. 179.

- ^ Kuzmin 2011, p. 417.

- ^ Kuzmin 2011, p. 187.

- ^ (in Russian) Kuzmin, S. L., Oyuunchimeg, J. and Bayar, B. The battle at Ulaankhad, one of the main events in the fight for independence of Mongolia Archived 21 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Studia Historica Instituti Historiae Academiae Scientiarum Mongoli, 2011–12, vol. 41–42, no 14, pp. 182–217

- ^ (in Russian) Kuzmin, S.L., Oyuunchimeg, J. and Bayar, B. The Ulaan Khad: reconstruction of a forgotten battle for independence of Mongolia Archived 21 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Rossiya i Mongoliya: Novyi Vzglyad na Istoriyu (Diplomatiya, Ekonomika, Kultura), 2015, vol. 4. Irkutsk, pp. 103–14.

- ^ Knyazev, N. N. "The Legendary Baron". In Kuzmin (2004a), pp. 67–69.

- ^ Tornovsky 2004a, pp. 231–233.

- ^ . "Facsimile of the original and translations of the Bogd Khan edict". In Kuzmin (2004b), pp. 90–92.

- ^ Kuzmin 2011, pp. 433–436.

- ^ Palmer 2008, pp. 182–183.

- ^ Palmer 2008, p. 184.

- ^ (in Russian) Kuzmin, S. L. and Rejt, L. J. Notes by F. A. Ossendowski as a source on the history of Mongolia Archived 21 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine in Vostok (Oriens) (Moscow), 2008. no 5, pp. 97–110

- ^ Kuzmin 2011, pp. 406–418.

- ^ (in Russian) Kuzmin S.L., Batsaikhan, O., Nunami, K. and Tachibana, M. 2009. Baron Ungern and Japan Archived 21 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine, in Vostok (Oriens) (Moscow), no 5, pp. 115–133

- ^ Kuzmin 2004b.

- ^ Kuzmin 2011, pp. 228–372.

- ^ Kuzmin 2011, p. 302.

- ^ Alioshin, Dmitri (1941). Asian Odyssey. London: Cassell and Co., Ltd. pp. 268–269.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Palmer 2008, p. 244.

- ^ Palmer 2008, p. 243.

- ^ Stuttaford, Andrew (6 July 2009). "The Heart of Darkness". AndrewStuttaford.com. Archived from the original on 27 September 2016. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

Sources[]

- Kuzmin, Sergei L., ed. (2004a). Legendarnyi Baron: Neizvestnye Stranitsy Grazhdanskoi Voiny (in Russian). Moscow: KMK Sci. Press. ISBN 978-5-87317-175-0.

- Tornovsky, M. G. "Events in Mongolia-Khalkha in 1920–1921". In Kuzmin (2004a).

- Kuzmin, Sergei L., ed. (2004b). Baron Ungern v Dokumentakh i Memuarakh (in Russian). Moscow: KMK Sci. Press. ISBN 978-5-87317-164-4.

- Kuzmin, Sergei L. (2011). The History of Baron Ungern. An Experience of Reconstruction. Moscow: KMK Sci. Press. ISBN 978-5-87317-692-2.

- Kuzmin, Sergei L. (2013). "How bloody was the White Baron?". Inner Asia. 15 (1).

- Palmer, James (2008). The Bloody White Baron: The Extraordinary Story of the Russian Nobleman Who Became the Last Khan of Mongolia. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 9780571230242.

- Pershin, D. P. (1999). Baron Ungern, Urga i Altanbulak (in Russian). Samara: Agni. ISBN 978-5898500030.

- Smith, Canfield F. (1980). "The Ungernovščina – How and Why?". Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas. 28 (4): 590–595. JSTOR 41046201.

- Sunderland, Willard (2014). The Baron's Cloak: A History of the Russian Empire in War and Revolution. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-5270-3.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Roman Ungern. |

- Willard Sunderland, The Baron’s Cloak, A History of the Russian Empire in War and Revolution review by Nikolaus Katzer

- Hughes, Kathryn. Review: The Bloody White Baron by James Palmer, The Guardian, 14 June 2008.

- Goodwin, Jason. Book Review 'The Bloody White Baron,' by James Palmer

- Willard Sunderland on New Books Network (audio here) discussing his book, The Baron's Cloak: A History of the Russian Empire in War and Revolution (Cornell University Press, 2014, ISBN 978-0-8014-5270-3)

- 1886 births

- 1921 deaths

- Military personnel from Graz

- Baltic German people of the Russian Empire

- Nobility of the Russian Empire

- Expatriates of the Russian Empire in Austria-Hungary

- People of the Russian Civil War

- Russian military personnel of World War I

- Anti-communists of the Russian Empire

- Generals of the Russian Empire

- Monarchists of the Russian Empire

- Warlords

- White movement generals

- People executed by the Soviet Union

- People from the Governorate of Estonia

- People executed by Russia by firing squad

- People of the Russian Empire of Hungarian descent

- People of the Russian Empire of Tatar descent

- Lutherans of the Russian Empire