Rouran Khaganate

Rouran Khaganate | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 330 AD–555 AD | |||||||||||||

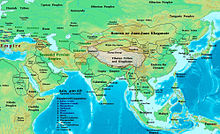

Rouran Khaganate in Central Asia | |||||||||||||

| Status | Khaganate | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Ting northwest of Gansu[1] Mumocheng[1] | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Rouran Mongolian Old Turkic Chinese | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Tengrism Shamanism Buddhism | ||||||||||||

| Khagan | |||||||||||||

• 330 AD | Yujiulü Mugulü | ||||||||||||

• 555 AD | Yujiulü Dengshuzi | ||||||||||||

| Legislature | Kurultai | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

• Established | 330 AD | ||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 555 AD | ||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

| 405[2][3] | 2,800,000 km2 (1,100,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | China Kazakhstan Mongolia Russia | ||||||||||||

| Rouran | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 柔然 | ||

| |||

| Ruru or Ruanruan | |||

| Chinese | 蠕蠕 | ||

| |||

| Ruru | |||

| Chinese | 茹茹 | ||

| |||

| Ruirui | |||

| Chinese | 芮芮 | ||

| |||

| Rouru or Rouruan | |||

| Chinese | 蝚蠕 | ||

| |||

| Tantan | |||

| Chinese | 檀檀 | ||

| |||

| History of Mongolia |

|---|

The Rouran Khaganate, also Juan-Juan Khaganate (Chinese: 柔然; pinyin: Róurán),[4][5] was a tribal confederation and later state founded by a people of Proto-Mongolic Donghu origin.[6] The Rouran supreme rulers are noted for being the first to use the title of "khagan", having borrowed this popular title from the Xianbei.[7] The Rouran Khaganate lasted from the late 4th century until the middle 6th century, when they were defeated by a Göktürk rebellion which subsequently led to the rise of the Turks in world history.

Their Khaganate overthrown, some Rouran remnants possibly became Tatars[8][9] while others possibly migrated west and became the Pannonian Avars (known by such names as Varchonites or Pseudo Avars), who settled in Pannonia (centred on modern Hungary) during the 6th century.[10] However, this Rouran-Avars link remains a controversial theory. The Avars were pursued into the Byzantine Empire by the Göktürks, who referred to the Avars as a slave or vassal people, and requested that the Byzantines expel them. Other theories instead link the origins of the Pannonian Avars to peoples such as the Uar.

Considered an imperial confederation, the Rouran Khaganate was based on the "distant exploitation of agrarian societies," although many researchers claim that the Rouran had a feudal system, or "nomadic feudalism." The Rouran controlled trade routes, and raided and subjugated oases and outposts such as Gaochang. Their society is said to show the signs of "both an early state and a chiefdom." The Rouran have been credited as "a band of steppe robbers," because they adopted a strategy of raids and extortion of Northern China. The Khaganate was an aggressive militarized society, a "military-hierarchical polity established to solve the exclusively foreign-policy problems of requisitioning surplus products from neighbouring nations and states."[1]

Name[]

Nomenclature[]

Róurán 柔然 is a Classical Chinese transcription of the endonym of the confederacy;[11] 蠕蠕 Ruǎnruǎn ~ Rúrú (Weishu), however, was used in Tuoba-Xianbei sources such as orders given by Emperor Taiwu of Northern Wei.[12] It meant something akin to "wriggling worm" and was used in a derogatory sense.[13] Other transcriptions are 蝚蠕 Róurú ~ Róuruǎn (Jinshu); 茹茹 Rúrú (Beiqishu, Zhoushu, Suishu); 芮芮 Ruìruì (Nanqishu, Liangshu, Songshu), 大檀 Dàtán and 檀檀 Tántán (Songshu).

Mongolian Sinologist Sühe Baatar suggests Nirun Нирун as the modern Mongolian term for the Rouran, as Нирун superficially resembles reconstructed Chinese forms beginning with *ń- or *ŋ-. Rashid-al-Din Hamadani recorded Niru'un and Dürlükin as two divisions of the Mongols.[14]

Etymology[]

Klyastorny reconstructed the ethnonym behind the Chinese transcription 柔然 Róurán (LHC: *ńu-ńan; EMC: *ɲuw-ɲian > LMC: *riw-rian) as *nönör and compares it to Mongolic нөкүр nökür "friend, comrade, companion" (Khalkha нөхөр nöhör). According to Klyashtorny, *nönör denotes "stepnaja vol'nica" "a free, roving band in the steppe, the 'companions' of the early Rouran leaders." In early Mongol society, a nökür was someone who had left his clan or tribe to pledge loyalty to and serve a charismatic warlord; if this derivation were correct, Róurán 柔然 was originally not an ethnonym, but a social term referring the dynastic founder's origins or the core circle of companions who helped him build his state.[15]

However, Golden identifies philological problems: the ethnonym should have been *nöŋör to be cognate to nökür, & possible assimilation of -/k/- to -/n/- in Chinese transcription needs further linguistic proofs. Even if 柔然 somehow transmitted nökür, it more likely denoted the Rouran's status as the subjects of the Tuoba. Before being used as an ethnonym, Rouran had originally been the byname of chief Cheluhui (车鹿会), possibly denoting his status "as a Wei servitor".[16]

History[]

Origin[]

Primary Chinese-language sources Songshu and Liangshu connected Rouran to the earlier Xiongnu (of unknown ethnolinguistic affiliation) while Weishu traced the Rouran's origins back to the Donghu,[17] generally agreed to be Proto-Mongols.[18] Xu proposed that "the main body of the Rouran were of Xiongnu origin" and Rourans' descendants, namely Da Shiwei (aka Tatars), contained Turkic elements, besides Mongolic Xianbei.[8] Even so, the Xiongnu's language is still unknown[19] and Chinese historians routinely ascribed Xiongnu origins to various nomadic groups, yet such ascriptions do not necessarily indicate the subjects' exact origins: for examples, Xiongnu ancestry was ascribed to Turkic-speaking Göktürks and Tiele as well as Para-Mongolic-speaking Kumo Xi and Khitans.[20]

Kwok Kin Poon additionally proposes that the Rouran were descended specifically from Donghu's Xianbei lineage,[21] i.e. from Xianbei who remained in the eastern Eurasian Steppe after most Xianbei had migrated south and settled in Northern China.[22] Genetic testings on Rourans' remains suggested Donghu-Xianbei paternal genetic contribution to Rourans.[23]

Khaganate[]

The founder of the Rouran Khaganate, Yujiulu Shelun, was said to be descended from the mythological founder Mugulü, who, according to Chinese-language chronicles (Weishu, Beishi), was captured and enslaved by Xianbei raiders.[1] The anecdote of the founder of the Rouran being a slave is a "typical insertion by the Chinese historians intended to show the low birth and barbarian nature of the northern nomads."[1] The endonym Rouran itself was distorted by the Sinicized Tuoba Xianbei into exonyms Ruru or Ruanruan, meaning something akin to "wriggling worms". After the Xianbei migrated south and settled in Chinese lands during the late 3rd century AD, the Rouran made a name for themselves as fierce warriors. However they remained politically fragmented until 402 AD when Shelun gained support of all the Rouran chieftains and united the Rouran under one banner. Immediately after uniting, the Rouran entered a perpetual conflict with Northern Wei, beginning with a Wei offensive that drove the Rouran from the Ordos region. The Rouran expanded westward and defeated the neighboring Tiele people and expanded their territory over the Silk Roads, even vassalizing the Hephthalites which remained so until the beginning of the 5th century.[24][25] The Hepthalites migrated southeast due to pressure from the Rouran and displaced the Yuezhi in Bactria, forcing them to migrate further south. Despite the conflict between the Hephthalites and Rouran, the Hephthalites borrowed much from their eastern overlords, in particular the title of "Khan" which was first used by the Rouran as a title for their rulers.[25]

The Rouran were considered vassals (chen) by Tuoba Wei. By 506 they were considered a vassal state (fanli). They were considered equal partners by the Chinese empire. Following the growth of Rouran and the turning of Wei into a classical Chinese state, they were considered partners of equal rights by Wei (lindi gangli).[25]

In 424, the Rouran invaded Northern Wei but were repulsed.[26]

In 429, Northern Wei launched a major offensive against the Rouran and killed a large number of people.[24]

The Chinese are foot soldiers and we are horsemen. What can a herd of colts and heifers do against tigers or a pack of wolves? As for the Rouran, they graze in the north during the summer; in autumn, they come south and in winter raid our frontiers. We have only to attack them in summer in their pasture lands. At that time their horses are useless: the stallions are busy with the fillies, and the mares with their foals. If we but come upon them there and cut them off from their grazing and their water, within a few days they will be either taken or destroyed.[24]

— Emperor Daowu of Northern Wei

In 434, the Rouran entered a marriage alliance with Northern Wei.[27]

In 443, Northern Wei attacked the Rouran.[24]

In 449, the Rouran were defeated in battle by Northern Wei.[28]

In 456, Northern Wei attacked the Rouran.[24]

In 458, Northern Wei attacked the Rouran.[24]

In 460, the Rouran subjugated the Ashina tribe residing around modern Turpan and resettled them in the Altai Mountains.[29] The Rouran also ousted the previous dynasty of Gaochang and installed Kan Bozhou as its king.[24]

In 492, Emperor Tuoba Hong sent 70 thousand horsemen against Rouran. Because Chinese sources are silent about the outcome of the expedition, it is probable that it was unsuccessful.[1] However, possibly strained after the battle with Wei, the Rourans were not able to prevent the Uighur chief Abuzhiluo from heading "a 100 thousand tents" west, in a series of events that led to the overthrowing and killing of Doulun Khan.[1] Two armies were sent in pursuit of the rebels, one led by Doulun, the other by Nagai, his uncle. The Rouran emerged victorious. In the war against the Uighurs, Doulan fought well, but his uncle Nagai won all the battles against the Uighurs. Thus, the soldiers thought that Heaven didn't favor Doulan anymore, and that he should be deposed in favor of Nagai. The latter, who was faithful to traditions, declined. Nonetheless, the subjects killed Doulan and murdered his next of kin, installing Nagai on the throne.[1]

In 518, Nagai marries the sorceress Diwan, conferring her the title of khagatun for her outstanding service.[1]

Between 525 and 527, Rouran was employed by Northern Wei in the suppression of rebellions in their territory, with the Rourans then plundering the local population.[1]

The Rouran Khaganate arranged for one of their princesses, Khagan Yujiulü Anagui's daughter Princess Ruru, to be married to the Han Chinese ruler Gao Huan of the Eastern Wei.[30]

Heqin[]

The Rourans were involved many times in Royal intermarriage (also known as Heqin in China), with the Northern Yan and especially with the Northern Wei dynasty and its successors Eastern and Western Wei, which were fighting each other, and each seeking the support of Rouran to defeat the other. These royal intermarriages meant instances of Chinese dynasties' princesses marrying Rouran princes or khagans (e.g. Princess Lelang, Princess Lanling) and Rouran princesses marrying Chinese dynasties' rulers and princes (e.g. Princess Ruru, Empress Gong). Both parties, in turn, took the initiative of proposing such marriages to forge important alliances or solidify relations, with the warring Western Wei and Eastern Wei oftener seeking the Rourans in the latter period. The so-called "diplomatic princesses" were well treated and honored on both sides. In the 1970s, the Tomb of Princess Linhe was unearthed in Ci County, Hebei. It contained artistically invaluable murals, a mostly pillaged but still consistent treasure, Byzantine coins and about a thousand vessels and clay figurines. Among the latter was the figurine of a Shaman, standing in a dancing posture and holding a saw-like instrument. The Rouran would often visit their now allies and now rivals of Eastern Wei, and this figurine is thought to reflect the young princess' Rouran/nomadic roots.[31]

On one occasion, in 540, the Rourans attacked Western Wei reportedly with a million warriors because a Rouran princess reported being dissatisfied with being second to Emperor Wendi's principal wife.[31]

The first khagan Shelun is said to have concluded a “treaty of peace based on kinship” (huoqin) with the rulers of Jin.[1] The royal house of Rouran is also said to have intermarried with the royal house of the Haital (Hephthalites) in the 6th century.[32]

Society[]

Since the time of Shelun Khan, the khans were bestowed with additional titles at their enthronement. Since 464, starting with Yucheng Khan they started to use epoch names, like the Chinese. The Rouran dignitaries of the ruling elite also adopted nicknames, referring to their deeds, similarly to the titles the Chinese gave posthumously. This practice is analogous with that of later Mongolian chiefs. There was a wide circle composing the nomadic aristocracy, including elders, chieftains, military commanders. The grandees could be high or low ranking. The khagan could confer titles in reward of services rendered and outstanding deeds, such as in 518, when Nagai entitled the sorceress Diwai khagatun, taking her as his wife, and gave a compensation, a post and a title to Fushengmou, her then former husband.[1] The Rouran titles included mofu, mohetu (cf. Mongolian batur, baghatur), mohe rufei (cf. Mongolian baga köbegün), hexi, sili and sili-mohe, totoufa, totouteng, sijin (cf. Turkic irkin), xielifa (cf. Turkic eltäbär).

Sources indicate that slave ownership existed among the Rouran. In 521, Khagan Anagui was given two female slaves as a gift from the Chinese; included among the penalties and rewards introduced with the reorganization of the military and the state carried out by Shelun, there was the regulation that soldiers who fought outstandingly would receive captives. There is also evidence that the Rouran resettled people in the steppe.[1]

Initially the Rouran chiefs, according to Chinese sources, having no letters to make records, "counted approximately the number of warriors by using sheep's droppings." Later, they made records using notches on wood. They adopted the Chinese written language, using it to make records and write diplomatic letters, and, with Anagui, started using it to write internal records. There is also evidence of a large number of literate people among the Rouran.[1] This high level of literacy reportedly didn't affect only the elites, but also common people such as cattle-breeders, who were able to use ideograms.[1] In the Book of Song there is the story of an educated Rouran "whose knowledge shamed a wise Chinese functionary."[1] Further, it is not excluded that they had their own runic script.[1]

There is no record of monuments erected by the Rouran, though there is evidence of the latter requesting doctors, weavers and other artisans to be sent from China.[1]

Imitating the Chinese, Anagui Khan introduced the use of officials at court, adopted a staff of bodyguards, or chamberlains, and "surrounded himself with advisers trained in the tradition of Chinese bibliophily." His chief advisor was the Chinese Shunyu Tan, whose role is comparable to that of Yelü Chucai with the Mongols and Zhonghang Yue with the Xiongnu (or Huns).[1]

Capital[]

The capital of the Rouran likely changed over time. The headquarters of the Rouran Khan (ting) was initially northwest of Gansu. Later the capital of the Rouran became Mumocheng, "encircled with two walls constructed by Liang shu."[1] The existence of this city would be proof of early urbanization among the Rouran.[1] However, its location is disputed, and no trace of it has been found so far.[1]

Decline[]

In 461, Lü Pi, Duke of Hedong, a Northern Wei general and Grand chancellor of Rouran descent, dies in Northern Wei.

The Rouran and the Hephthalites had a falling out and problems within their confederation were encouraged by Chinese agents.

In 508, the Tiele defeated the Rouran in battle.

In 516, the Rouran defeated the Tiele.

In 551, Bumin of the Ashina Göktürks quelled a Tiele revolt for the Rouran and asked for a Rouran princess for his service. The Rouran refused and in response Bumin declared independence.[34] Bumin entered a marriage alliance with Western Wei, a successor state of Northern Wei, and attacked the Rouran in 552. The Rouran, now at the peak of their might, were defeated by the Turks. After a defeat at Huaihuang (in present-day Zhangjiakou, Hebei) the last great khan Anagui, realizing he had been defeated, took his own life. Bumin declared himself Illig Khagan of the Turkic Khaganate after conquering Otuken; Bumin died soon after and his son Issik Qaghan succeeded him. Issik continued attacking the Rouran, their khaganate now fallen into decay, but died a year later in 553.

In 555, Turks invaded and occupied the Rouran and Yujiulü Dengshuzi led 3000 soldiers in retreat to Western Wei.[35] He was later delivered to Turks by Emperor Gong with his soldiers under pressure from Muqan Qaghan.[36] In the same year, Muqan is said to have annihilated the Rouran.[34][37] All the Rouran handed over to the Turks, reportedly with the exception of children less than sixteen,[1] were brutally killed.[1]

On 29 November 586 Yujiulü Furen (郁久闾伏仁), an official of Sui and a descendant of the ruling clan, dies in Hebei, leaving an epitaph reporting his royal descent from the Yujiulü clan.[38]

Possible descendants[]

Tatars[]

According to Xu (2005), some Rouran remnants fled to the northwest of the Greater Khingan mountain range, and renamed themselves 大檀 Dàtán (MC: *daH-dan) or 檀檀 Tántán (MC: *dan-dan) after Tantan, personal name of a historical Rouran Khagan. Tantan were gradually incorporated into the Shiwei tribal complex and later emerged as Great-Da Shiwei (大室韋) in Suishu.[8] Klyashtorny, apud Golden (2013), reconstructed 大檀 / 檀檀 as *tatar / dadar, "the people who, [Klyashtorny] concludes, assisted Datan in the 420s in his internal struggles and who later are noted as the Otuz Tatar ("Thirty Tatars") who were among the mourners at the funeral of Bumın Qağan (see the inscriptions of Kül Tegin, E4 and Bilge Qağan, E5)".[39]

Avars[]

Some scholars claim that the Rouran then fled west across the steppes and became the Avars, though many other scholars contest this claim.[40] However, it's unlikely that Rouran would have migrated to Europe in any sufficient strength to establish themselves there, due to the desperate resistances, military disasters, and massacres.[36] The remainder of the Rouran fled into China, were absorbed into the border guards, and disappeared forever as an entity. The last khagan fled to the court of the Western Wei, but at the demand of the Göktürks, Western Wei executed him and the nobles who accompanied him.[citation needed]

Genetics[]

Li et al. 2018 examined the remains of a Rouran male buried at the Khermen Tal site in Mongolia. He was found to be a carrier of the paternal haplogroup C2b1a1b and the maternal haplogroup D4b1a2a1. Haplogroup C2b1a1b has also been detected among the Xianbei.[41]

Several genetic studies have shown that early Pannonian Avar elites carried a large amount of East Asian ancestry, and some have suggested this as evidence for a connection between the Pannonian Avars and the Rouran.[42] However, Savelyev & Jeong 2020 notes that there is still little genetic data on the Rouran themselves, and that their genetic relationship with the Pannonian Avars therefore still remains inconclusive.[43]

Language[]

The received view is that the relationships of the language remain a puzzle and that it may be an isolate.[44] Alexander Vovin (2004, 2010)[45][46] considers the Ruan-ruan language to be an extinct non-Altaic language that is not related to any modern-day language (i.e., a language isolate) and is hence unrelated to Mongolic. Vovin (2004) notes that Old Turkic had borrowed some words from an unknown non-Altaic language that may have been Ruan-ruan. In 2018 Vovin changed his opinion after new evidence was found through the analysis of the Brāhmī Bugut and Khüis Tolgoi inscriptions and suggests that the Ruanruan language was in fact a Mongolic language, close but not identical to Middle Mongolian.[47]

Rulers of the Rouran[]

The Rourans were the first people who used the titles Khagan and Khan for their emperors, replacing the Chanyu of the Xiongnu. The etymology of the title Chanyu is controversial: there are Mongolic,[48] Turkic,[49] Yeniseian versions.[50][51]

Tribal chiefs[]

- Yujiulü Mugulü, 4th century

- Yujiulü Cheluhui, 4th century

- , 4th century

- , 4th century

- , 4th century

- , 4th century

- , 4th century

- , 4th century

Khagans[]

| Personal name | Regnal name | Reign | Era names |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yujiulü Shelun | Qiudoufa Khagan (丘豆伐可汗) | 402–410 | |

| Yujiulü Hulü | Aikugai Khagan (藹苦蓋可汗) | 410–414 | |

| Yujiulü Buluzhen | 414 | ||

| Yujiulü Datan | Mouhanheshenggai Khagan (牟汗紇升蓋可汗) | 414–429 | |

| Yujiulü Wuti | Chilian Khagan (敕連可汗) | 429–444 | |

| Yujiulü Tuhezhen | Chu Khagan (處可汗) | 444–464 | |

| Yujiulü Yucheng | Shouluobuzhen Khagan (受羅部真可汗) | 464–485 | Yongkang (永康) |

| Yujiulü Doulun | Fumingdun Khagan (伏名敦可汗) | 485–492 | Taiping (太平) |

| Yujiulü Nagai | Houqifudaikezhe Khagan (侯其伏代庫者可汗) | 492–506 | Taian (太安) |

| Yujiulü Futu | Tuohan Khagan (佗汗可汗) | 506–508 | Shiping (始平) |

| Yujiulü Chounu | Douluofubadoufa Khagan (豆羅伏跋豆伐可汗) | 508–520 | Jianchang (建昌) |

| Yujiulü Anagui | Chiliantoubingdoufa Khagan (敕連頭兵豆伐可汗) | 520–521 | |

| Yujiulü Poluomen | Mioukesheju Khagan (彌偶可社句可汗) | 521–524 | |

| Yujiulü Anagui | Chiliantoubingdoufa Khagan (敕連頭兵豆伐可汗) | 522–552 |

Khagans of West[]

- Yujiulü Dengshuzi, 555

Khagans of East[]

- Yujiulü Tiefa, 552–553

- Yujiulü Dengzhu, 553

- Yujiulü Kangti, 553

- Yujiulü Anluochen, 553–554

Rulers family tree[]

| showThe family tree of the Khaghans of the Rouran |

|---|

See also

References[]

Citations[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Kradin NN (2005). "FROM Tribal Confederation to Empire: The Evolution of the Rouran Society". Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. Volume 58 (2), 149–169 (2005): 1-21 (149-169).

|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Taagepera, Rein (1979). "Size and Duration of Empires: Growth-Decline Curves, 600 B.C. to 600 A.D.". Social Science History. 3 (3/4): 129. doi:10.2307/1170959. JSTOR 170959.

- ^ Turchin, Peter; Adams, Jonathan M.; Hall, Thomas D (December 2006). "East-West Orientation of Historical Empires". Journal of World-Systems Research. 12 (2): 222. ISSN 1076-156X. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^ Zhang, Min. "On the Defensive System of Great Wall Military Town of Northern Wei Dynasty" China's Borderland History and Geography Studies, Jun. 2003 Vol. 13 No. 2. Page 15.

- ^ Kradin, Nikolay N. (2016). Rouran (Juan Juan) Khaganate in "The Encyclopedia of Empire". John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. 1–2.

- ^ Wei Shou. Book of Wei. vol. 103 "蠕蠕,東胡之苗裔也,姓郁久閭氏" tr. "Rúrú, offsprings of Dōnghú, surnamed Yùjiŭlǘ"

- ^ Vovin, Alexander (2007). "Once again on the etymology of the title qaγan". Studia Etymologica Cracoviensia, vol. 12 (online resource)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Xu Elina-Qian, Historical Development of the Pre-Dynastic Khitan, University of Helsinki, 2005. pp. 179–180

- ^ Golden, Peter B. "Some Notes on the Avars and Rouran", in The Steppe Lands and the World beyond Them. Ed. Curta, Maleon. Iași (2013). pp. 54–56.

- ^ Findley (2005), p. 35.

- ^ Weishu Vol. 103 "木骨閭死,子車鹿會雄健,始有部眾,自號柔然" "Mugulü died; [his] son Cheluhui, fierce and vigorous, began to gather the tribal multitude, [his/their] self-appellation Rouran"

- ^ Weishu Vol. 103 "而役屬於國。後世祖以其無知,狀類於蟲,故改其號為蠕蠕。" tr. "yet [Cheluhui/Rouran] [was/were] vassal(s) of (our) state. Later, (Emperor) Shizu took him/them as ignorant and [his/their] appearance worm-like, so [the Emperor] changed his/their appellation to Ruanruan ~ Ruru"

- ^ Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 60–61. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- ^ Golden, Peter B. "Some Notes on the Avars and Rouran", in The Steppe Lands and the World beyond Them. Ed. Curta, Maleon. Iași (2013). p. 54.

- ^ Golden, Peter B. (2016) "Turks and Iranians: Aspects of Türk and Khazaro-Iranian Interaction" in Turcologica 105. p. 5

- ^ Golden, Peter B. "Some Notes on the Avars and Rouran", in The Steppe Lands and the World beyond Them. Ed. Curta, Maleon. Iași (2013). p. 58.

- ^ Golden, Peter B. "Some Notes on the Avars and Rouran", in The Steppe Lands and the World beyond Them. Ed. Curta, Maleon. Iași (2013). pp. 54–55.

- ^ *Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (2000). "Ji 姬 and Jiang 姜: The Role of Exogamic Clans in the Organization of the Zhou Polity", Early China. p. 20

- ^ Lee, Joo-Yup (2016). "The Historical Meaning of the Term Turk and the Nature of the Turkic Identity of the Chinggisid and Timurid Elites in Post-Mongol Central Asia". Central Asiatic Journal. 59 (1–2): 116.

It is not known which language the Xiongnu spoke.

- ^ Lee, Joo-Yup (2016). "The Historical Meaning of the Term Turk and the Nature of the Turkic Identity of the Chinggisid and Timurid Elites in Post-Mongol Central Asia". Central Asiatic Journal. 59 (1–2): 105.

- ^ "The Northern Wei state and the Juan-juan nomadic tribe". The University of Hong Kong Scholar hub. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- ^ Hyacinth (Bichurin), Collection of information on peoples lived in Central Asia in ancient times, 1950. p. 209

- ^ Li, Jiawei; et al. (August 2018). "The genome of an ancient Rouran individual reveals an important paternal lineage in the Donghu population". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. American Association of Physical Anthropologists. 166 (4): 895–905. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23491. PMID 29681138.

We conclude that F3889 downstream of F3830 is an important paternal lineage of the ancient Donghu nomads. The Donghu‐Xianbei branch is expected to have made an important paternal genetic contribution to Rouran. This component of gene flow ultimately entered the gene pool of modern Mongolic‐ and Manchu‐speaking populations.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Grousset (1970), p. 67.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Kurbanov, A. The Hephthalites: Archaeological and historical analysis. PhD dissertation, Free University, Berlin, 2010

- ^ Grousset 1970, p. 61.

- ^ Xiong 2009, p. xcix.

- ^ Xiong 2009, p. c.

- ^ Bregel 2003, p. 14.

- ^ Lee, Lily Xiao Hong; Stefanowska, A. D. (2007). Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: Antiquity Through Sui, 1600 B.C.E.-618 C.E. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-4182-3. p. 316.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cheng, Bonnie (2007). "Fashioning a Political Body: The Tomb of a Rouran Princess". Archives of Asian Art. Duke University Press (via JSTOR). Vol. 57: 23–49. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ David Sneath, University Assistant Lecturer in the Department of Social Anthropology and Assistant Director of the Mongolia and Inner Asia Studies Unit David Sneath, David (Director Sneath, Mongolia and Inner Asia Studies Unit University of Cambridge) (2007). The Headless State Aristocratic Orders, Kinship Society, & Misrepresentations of Nomadic Inner Asia. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231140546.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- ^ Abe, Stanley Kenji (1989). Mogao Cave 254 A Case Study in Early Chinese Buddhist Art. University of California, Berkeley. p. 147.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Barfield 1989, p. 132.

- ^ Kuwayama, S. (2002). Across the Hindukush of the First Millennium: a collection of the papers. Institute for Research in Humanities, Kyoto University. p. 123.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pohl, Walter (15 December 2018). The Avars: A Steppe Empire in Central Europe, 567–822. Cornell University Press. p. 36. ISBN 9781501729409.

- ^ Xiong 2009, p. 103.

- ^ "隋代《郁久闾伏仁墓志》考释-中国文物网-文博收藏艺术专业门户网站" [An Interpretation of the Epitaph of Yujiulü Furen]. www.wenwuchina.com. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ Golden, Peter B. "Some Notes on the Avars and Rouran", in The Steppe Lands and the World beyond Them. Ed. Curta, Maleon. Iași (2013). p. 54-56.

- ^ "Avars". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ Li et al. 2018, pp. 1, 8–9.

- ^ Neparáczki et al. 2019, pp. 5–6, 9. "The Avar group carried predominantly East Eurasian lineages in accordance with their known Inner Asian origin inferred from archaeological and anthropological parallels as well as historical sources. However, the unanticipated prevalence of their Siberian N1a Hg-s, sheds new light on their prehistory. Accepting their presumed Rouran origin would implicate a ruling class with Siberian ancestry in Inner Asia before Turkic take-over. The surprisingly high frequency of N1a1a1a1a3 Hg reveals that ancestors of contemporary eastern Siberians and Buryats could give a considerable part the Rouran and Avar elite..."; Csáky et al. 2020, pp. 1, 9. "A recent manuscript described 23 mitogenomes from the 7th–8th century Avar elite group5 and found that 64% of the lineages belong to East Asian haplogroups (C, D, F, M, R, Y and Z) with affinities to ancient and modern Inner Asian populations corroborating their Rouran origin."

- ^ Savelyev & Jeong 2020, p. 17. "Population genetics in the current state of research is neutral as regards the question of continuity between the Rourans and the Avars. What it is supported is that at least some European Avar individuals were of Eastern Asian ancestry, be it Rouran-related or not."

- ^ Crossley, Pamela Kyle (2019). Hammer and Anvil: Nomad Rulers at the Forge of the Modern World. p. 49.

- ^ Vovin, Alexander 2004. 'Some Thoughts on the Origins of the Old Turkic 12-Year Animal Cycle.' Central Asiatic Journal 48/1: 118–32.

- ^ Vovin, Alexander. 2010. Once Again on the Ruan-ruan Language. Ötüken’den İstanbul’a Türkçenin 1290 Yılı (720–2010) Sempozyumu From Ötüken to Istanbul, 1290 Years of Turkish (720–2010). 3–5 Aralık 2010, İstanbul / 3–5 December 2010, İstanbul: 1–10.

- ^ Vovin, Alexander (2019). "A Sketch of the Earliest Mongolic Language: the Brāhmī Bugut and Khüis Tolgoi Inscriptions". International Journal of Eurasian Linguistics. 1 (1): 162–197. doi:10.1163/25898833-12340008. ISSN 2589-8825.

- ^ Таскин В. С. (1984). Материалы по истории древних кочевых народов группы дунху. Москва: Наука. Н. Ц. Мункуев. pp. 305–306.

- ^ Grousset (1970), pp. 61, 585, n. 91.

- ^ Vovin A. "Once again on the Etymology of the title qaɣan", in Studia Etyologica Crocoviensia, (2007) vol. 12, p. 177-185.

- ^ Vovin A. "Did the Xiongnu speak a Yeniseian language? Part 2: Vocabulary", in Altaica Budapestinensia MMII, Proceedings of the 45th Permanent International Altaistic Conference, Budapest, June 23–28, pp. 389–394.

- ^ "隋代《郁久闾伏仁墓志》考释-中国文物网-文博收藏艺术专业门户网站" [An Interpretation of the Epitaph of Yujiulü Furen]. www.wenwuchina.com. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

Sources[]

- Barfield, Thomas (1989), The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China, Basil Blackwell

- Bregel, Yuri (2003), An Historical Atlas of Central Asia, Brill

- Csáky, Veronika; et al. (22 January 2020). "Genetic insights into the social organisation of the Avar period elite in the 7th century AD Carpathian Basin". Scientific Reports. Nature Research. 10 (948): 948. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10..948C. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-57378-8. PMC 6976699. PMID 31969576.

- Findley, Carter Vaughn. (2005). The Turks in World History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-516770-8 (cloth); ISBN 0-19-517726-6 (pbk).

- Golden, Peter B.. "Some Notes on the Avars and Rouran", in The Steppe Lands and the World beyond Them. Ed. Curta, Maleon. Iași (2013). pp. 43–66.

- Grousset, René. (1970). The Empire of the Steppes: a History of Central Asia. Translated by Naomi Walford. Rutgers University Press. New Brunswick, New Jersey, U.S.A.Third Paperback printing, 1991. ISBN 0-8135-0627-1 (casebound); ISBN 0-8135-1304-9 (pbk).

- Li, Jiawei; et al. (August 2018). "The genome of an ancient Rouran individual reveals an important paternal lineage in the Donghu population". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. American Association of Physical Anthropologists. 166 (4): 895–905. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23491. PMID 29681138.

- Neparáczki, Endre; et al. (12 November 2019). "Y-chromosome haplogroups from Hun, Avar and conquering Hungarian period nomadic people of the Carpathian Basin". Scientific Reports. Nature Research. 9 (16569): 16569. Bibcode:2019NatSR...916569N. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-53105-5. PMC 6851379. PMID 31719606.

- Map of their empire

- Definition Archived 17 September 2003 at the Wayback Machine

- information about the Rouran Archived 18 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Kradin, Nikolay. "From Tribal Confederation to Empire: the Evolution of the Rouran Society". Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, Vol. 58, No 2 (2005): 149–169.

- Savelyev, Alexander; et al. (7 May 2020). "Early nomads of the Eastern Steppe and their tentative connections in the West". Evolutionary Human Sciences. Cambridge University Press. 2 (e20). doi:10.1017/ehs.2020.18.

- Xiong, Victor Cunrui (2000), Sui-Tang Chang'an: A Study in the Urban History of Late Medieval China (Michigan Monographs in Chinese Studies), University of Michigan Center for Chinese Studies, ISBN 0892641371

- Xiong, Victor Cunrui (2009), Historical Dictionary of Medieval China, United States of America: Scarecrow Press, Inc., ISBN 978-0810860537

External links[]

Media related to Rouran Khaganate at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Rouran Khaganate at Wikimedia Commons

- Rouran

- Khanates

- History of Mongolia

- Nomadic groups in Eurasia

- Ancient peoples of China

- Former countries in Chinese history

- Inner Asia

- States and territories established in the 4th century

- 555 disestablishments

- States and territories disestablished in the 6th century

- 330 establishments

- Donghu people