Royal New Zealand Navy

This article includes a list of general references, but it remains largely unverified because it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (March 2012) |

| Royal New Zealand Navy | |

|---|---|

| Māori: Te Taua Moana o Aotearoa | |

| |

| Founded | 1 October 1941 |

| Country | New Zealand |

| Type | Navy |

| Role | Naval warfare |

| Size | Personnel:

Ships:

|

| Part of | New Zealand Defence Force |

| Garrison/HQ | Devonport Naval Base |

| March | Quick: "Heart of Oak"; slow: "E Pari Ra" |

| Mascot(s) | Anchor |

| Anniversaries | 1 October 1941 (founded) |

| Engagements | World War II Korean War Malayan Emergency Cross border attacks in Sabah Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation Iran–Iraq War Gulf War Solomon Islands East Timor Operation Enduring Freedom |

| Website | navy |

| Commanders | |

| Governor-General and Commander-in-Chief | Dame Patsy Reddy |

| Chief of Defence Force | Air Marshal Kevin Short |

| Chief of Navy | Rear Admiral David Proctor |

| Commodore Melissa Ross | |

| Insignia | |

| Crest |  |

| Logo |  |

| Naval ensign |  |

| Naval jack |  |

| Queen's Colour |  |

The Royal New Zealand Navy (RNZN; Māori: Te Taua Moana o Aotearoa, literally: Sea Warriors of New Zealand) is the maritime arm of the New Zealand Defence Force. The fleet currently consists of nine ships.

History[]

Pre–World War I[]

The first recorded maritime combat activity in New Zealand occurred when Māori in war waka attacked Dutch explorer Abel Tasman off the northern tip of the South Island in December 1642.

The New Zealand Navy did not exist as a separate military force until 1941.[1] The association of the Royal Navy with New Zealand began with the arrival of Lieutenant (later Captain) James Cook in 1769, who completed two subsequent journeys to New Zealand in 1773 and 1777. Occasional visits by Royal Navy ships were made from the late 18th century until the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840. William Hobson, a crucial player in the drafting of the treaty, was in New Zealand as a captain in the Royal Navy. The signing of the Treaty of Waitangi made New Zealand a colony in the British Empire, so the defence of the coastline became the responsibility of the Royal Navy. That role was fulfilled until World War I, and the Royal Navy also played a part in the New Zealand Wars: for example, a gunboat shelled fortified Māori pā from the Waikato River in order to defeat the Māori King Movement.

World War I and the Inter-War period[]

In 1909, the New Zealand government decided to fund the purchase of the battlecruiser HMS New Zealand for the Royal Navy, which saw action throughout World War I in Europe. The passing of the created the New Zealand Naval Forces, still as a part of the Royal Navy. The first purchase by the New Zealand government for the New Zealand Naval Forces was the cruiser HMS Philomel, which escorted New Zealand land forces to occupy the German colony of Samoa in 1914. Philomel saw further action under the command of the Royal Navy in the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, and the Persian Gulf. By 1917, she was worn out and dispatched back to New Zealand where she served as a depot ship in Wellington Harbour for minesweepers. In 1921 she was transferred to Auckland for use as a training ship. [2]

The New Zealand Naval Forces passed to the control of Commander-in-Chief, China, after the Royal Navy forces in Australia came under Canberra's control in 1911. From 1921 to 1941 the force was known as the New Zealand Division of the Royal Navy.[3] The cruiser Chatham along with the sloop Veronica arrived in 1920, Philomel was transferred to the Division in 1921, as was the sloop Torch, HMS Laburnum arrived in 1922 and then HMS Dunedin in 1924. HMS Diomede and the minesweeper HMS Wakakura arrived in 1926. Between World War I and World War II, the New Zealand Division operated a total of 14 ships, including the cruisers HMS Achilles (joined 31 March 1937) and HMS Leander, which replaced Diomede and Dunedin (replaced by Leander in 1937).

World War II[]

When Britain went to war against Germany in 1939, New Zealand officially declared war at the same time, backdated to 9.30 pm on 3 September local time. But the gathering in Parliament in Carl Berendsen's room (including Peter Fraser) could not follow Chamberlain's words because of static on the shortwave and waited until the Admiralty notified the fleet that war had broken out before Cabinet approved the declaration of war (the official telegram from Britain was delayed and arrived just before midnight).[4]

HMS Achilles participated in the first major naval battle of World War II, the Battle of the River Plate off the River Plate estuary between Argentina and Uruguay, in December 1939.[5] Achilles and two other cruisers, HMS Ajax and HMS Exeter, severely damaged the German pocket battleship Admiral Graf Spee. The German Captain Hans Langsdorff then scuttled Graf Spee rather than face the loss of many more German seamen's lives. This decision apparently infuriated Hitler.

Achilles moved to the Pacific, and was working with the United States Navy (USN) when damaged by a Japanese bomb off New Georgia. Following repair, she served alongside the British Pacific Fleet until the war's end.

The New Zealand Division of the Royal Navy became the Royal New Zealand Navy (RNZN) from 1 October 1941, in recognition of the fact that the naval force was now largely self-sufficient and independent of the Royal Navy. The Prime Minister Peter Fraser reluctantly agreed, though saying "now was not the time to break away from the old country".[6] Ships thereafter were prefixed HMNZS (His/Her Majesty's New Zealand Ship).

HMNZS Leander escorted the New Zealand Expeditionary Force to the Middle East in 1940 and was then deployed in the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, and the Indian Ocean. Leander was subjected to air and naval attack from Axis forces, conducted bombardments, and escorted convoys. In February 1941, Leander sank the Italian auxiliary cruiser Ramb I in the Indian Ocean. In 1943, after serving further time in the Mediterranean, Leander returned to the Pacific Ocean. She assisted in the destruction of the Japanese cruiser Jintsu and being seriously damaged by torpedoes during the Battle of Kolombangara. The extent of the damage to Leander saw her docked for repairs until the end of the war.

As the war progressed, the size of the RNZN greatly increased, and by the end of the war, there were over 60 ships in commission. These ships participated as part of the British and Commonwealth effort against the Axis in Europe, and against the Japanese in the Pacific. They also played an important role in the defence of New Zealand, from German raiders, especially when the threat of invasion from Japan appeared imminent in 1942. Many merchant ships were requisitioned and armed for help in defence. One of these was HMNZS Monowai, which saw action against the Japanese submarine I-20 off Fiji in 1942. In 1941–1942, it was decided in an agreement between the New Zealand and United States governments that the best role for the RNZN in the Pacific was as part of the United States Navy, so operational control of the RNZN was transferred to the South West Pacific Area command, and its ships joined United States 7th Fleet taskforces.

In 1943, the light cruiser HMS Gambia was transferred to the RNZN as HMNZS Gambia. In November 1944, the British Pacific Fleet, a joint British Commonwealth military formation, was formed, based in Sydney, Australia. Most RNZN ships were transferred to the BPF, including Gambia and Achilles. They took part in the Battle of Okinawa and operations in the Sakishima Islands, near Japan. In August 1945, HMNZS Gambia was New Zealand's representative at the surrender of Japan. [7]

Post-World War II[]

During April 1947 a series of non-violent mutinies occurred amongst the sailors and non-commissioned officers of four RNZN ships and two shore bases. Overall, up to 20% of the sailors in the RNZN were involved in the mutinies. The resulting manpower shortage forced the RNZN to remove the light cruiser Black Prince, one of their most powerful warships, from service and set the navy's development and expansion back by a decade. Despite this impact, the size and scope of the events have been downplayed over time.[8]

RNZN ships participated in the Korean War. On 29 June, just four days after 135,000 North Korean troops crossed the 38th parallel in Korea, the New Zealand government ordered two Loch-class frigates – Tutira and Pukaki to prepare to make for Korean waters, and for the whole of the war, at least two NZ vessels would be on station in the theater.[9]

On 3 July, these two first ships left Devonport Naval Base, Auckland and joined other Commonwealth forces at Sasebo, Japan, on 2 August. These vessels served under the command of a British flag officer (seemingly Flag Officer Second in Command Far East Fleet)[10] and formed part of the US Navy screening force during the Battle of Inchon, performing shore raids and inland bombardment. Further RNZN Loch-class frigates joined these later – Rotoiti, Hawea, Taupo and Kaniere, as well as a number of smaller craft. Only one RNZN sailor was killed during the conflict – during the Inchon bombardments.

The Navy later participated in the Malayan Emergency. In 1954 a New Zealand frigate, HMNZS Pukaki, carried out a bombardment of a suspected guerilla camp, while operating with the Royal Navy's Far East Fleet – the first of a number of bombardments by RNZN ships over the next five years. , later to become Chief of Naval Staff decades later, wrote that in 1959, the RNZN "was still very much part of the Royal Navy supported by New Zealand tax-payers. The officer corps and senior specialist ratings were very dependent on loan and exchange RN personnel, while our own [New Zealand] officers and senior ratings were almost exclusively trained in the UK. We simply borrowed the RN's administrative regulations and amended them to local conditions. The Empire was alive and well. Operationally we were still very strongly tied to the UK."[11]

Later the Navy return to Malayan waters during the Indonesia-Malaysia confrontation. These operations were the RNZN's last large-scale operation with the Royal Navy. In a security crisis and threat to Malaysia and Sarawak and Brunei, two-thirds of the Royal Navy's operational warships were deployed from 1963 to the end of 1966 with Royalist, Taranaki, and Otago, heavily involved in boarding ships, shore patrols, presence, maintaining the use of seaways and support of the RN's amphibious carriers. The commitment, wrote Welch, "involved the whole fleet, as ships rotated though Pearl Harbour for workup with the USN before deploying on to the Far East to relieve ships on station."[12]

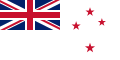

Until the 1960s, the RNZN had, in common with other Dominion navies, flown the White Ensign as a common ensign. After 1945, the foreign policies of the now-independent states had become more distinctive. There was a growing wish and a need for separate identities, particularly if one Dominion was engaged in hostilities where another was not. Thus, in 1968, the RNZN adopted its own ensign, which retained the Union Flag in a top quarter but replaces the St George's Cross with the Southern Cross constellation that is displayed on the national flag.

Since 1946, the Navy has policed New Zealand's territorial waters and exclusive economic zone for fisheries protection. It also aids New Zealand's scientific activities in Antarctica, at Scott Base.

One of the best-known roles that the RNZN played on the world stage was when the frigates Canterbury and Otago were sent by the Labour Government of Norman Kirk to Moruroa Atoll in 1973 to protest against French nuclear testing there. The frigates were sent into the potential blast zone of the weapons, where both ships witnessed one airburst test each which forced France to then change to underground testing.

In May 1982 Prime Minister Rob Muldoon seconded the frigate Canterbury to the Royal Navy for the duration of the Falklands War. Canterbury was deployed to the Armilla Patrol in the Persian Gulf, to relieve a British frigate for duty in the South Atlantic. Canterbury was herself relieved by Waikato in August.[13]

Post-Cold War[]

At the close of the Cold War the RNZN operated a surface combatant force of four frigates (HMNZS Waikato (F55), HMNZS Wellington (F69), HMNZS Canterbury (F421), and HMNZS Southland). Due to the post-Cold War restructuring of the RNZN the frigate fleet was downsized to two frigates, although there was considerable political debate at times during the mid-1990s about whether a third and fourth Anzac-class frigate should be procured.[14]

In the past three decades, the RNZN has operated in the Middle East a number of times. RNZN ships played a role in the Iran–Iraq War, aiding the Royal Navy in protecting neutral shipping in the Indian Ocean. Frigates were also sent to participate in the first Gulf War, and more recently Operation Enduring Freedom.[15] The RNZN has played an important part in conflicts in the Pacific as well. Naval forces were utilised in the Bougainville, Solomon Islands and East Timor conflicts of the 1990s. The RNZN often participates in United Nations peacekeeping operations.

The hydrographic survey ship of the RNZN until 2012 was HMNZS Resolution, succeeding the long-serving HMNZS Monowai. Resolution was used to survey and chart the sea around New Zealand and the Pacific Islands. A small motor boat, SMB Adventure, was operated from Resolution. Resolution carried some of the most advanced survey technology available.[16] HMNZS Resolution was decommissioned at Devonport Naval Base on 27 April 2012.[17]

White Ensign 1945–1968

White Ensign 1968–present

Queen's Colour of the Royal New Zealand Navy

Ships and aircraft[]

Current[]

The RNZN is currently in a transitional period where its role is being broadened into one that is more versatile than in the recent past. Formerly combat-oriented and based on the frigate, a number of new ships have been incorporated into the fleet that have given the RNZN a much broader platform from which to work.

Combat Force[]

The Combat Force consists of two Anzac-class frigates: HMNZS Te Kaha and HMNZS Te Mana.[18] Both ships are based at the Devonport Naval Base on Auckland's North Shore. Te Kaha was commissioned on 26 July 1997 and Te Mana on 10 December 1999. The specifications and armaments of the two ships are identical.[19][20]

Patrol Force[]

The Patrol Force consists of two offshore and two inshore patrol vessels.[18][21] The Patrol Force is responsible for policing New Zealand's Exclusive Economic Zone, one of the largest in the world. In addition, the Patrol Force provides assistance to a range of civilian government agencies, including the Department of Conservation, New Zealand Customs and Police, Ministry of Fisheries and others. The Patrol Force consists of:

- 2 Protector-class offshore patrol vessels (HMNZS Otago and HMNZS Wellington)

- 2 Lake-class inshore patrol vessels (HMNZS Hawea and HMNZS Taupo)

Support Force[]

- HMNZS Canterbury is a multi-role vessel that entered service in June 2007.[22]

- HMNZS Manawanui is a dive and hydrographic vessel commissioned in 2019.

- HMNZS Aotearoa is a replenishment oiler commissioned in 2020.

Hydrographics and diving[]

HMNZS Matataua (MAT) is a stone frigate with two operational groups for military hydrographics and clearance diving, and one logistics support group.[18][23] It combines the former teams for mine counter measures, maritime survey and operational diving and operates four REMUS 100 Autonomous underwater vehicles.[23] MAT is responsible for ensuring access to and the use of harbours, inshore waters and associated coastal zones.[18] The clearance diving group responsibilities include the disposal of explosive ordnance, beach reconnaissance in support of amphibious operations, underwater engineering and underwater search and recovery in support of the NZ Police.[24][25][26]

Aviation[]

The Royal New Zealand Air Force operates eight Kaman SH-2G Super Seasprite helicopters for use on the two frigates, the multi-role vessel and two offshore patrol craft.[27] These eight aircraft are part of No. 6 Squadron. The squadron is based at Whenuapai in Auckland, and helicopters are assigned to the ships as they are sent on deployments across the globe. The roles of the helicopters include:[27]

- surface warfare missions and surveillance operations

- underwater warfare

- helicopter delivery services/logistics

- search and rescue

- medical evacuation

- training

- assistance to other Government agencies

Future[]

Role[]

Defence[]

In its Statement of Intent, the NZDF states its primary mission as:

- "to secure New Zealand from external threat, to protect our sovereign interests, including in the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and to be able to take action to meet likely contingencies in our strategic area of interest."[28]

The intermediate outcomes of the NZDF are listed as:

- Secure New Zealand, including its people, land, territorial waters, exclusive economic zone, natural resources and critical infrastructure.

- Reduced risks to New Zealand from regional and global insecurity.

- New Zealand values and interests advanced through participation in regional and international security systems.

- New Zealand is able to meet future national security challenges.[29]

The role of the navy is to fulfil the maritime elements of the missions of the NZDF.

International participation[]

The RNZN has a role to help prevent any unrest occurring in New Zealand. This can be done by having a presence in overseas waters and assisting redevelopment in troubled countries. For example, any unrest in the Pacific Islands has the potential to affect New Zealand because of the large Pacific Island population. The stability of the South Pacific is considered in the interest of New Zealand. The navy has participated in peace-keeping and peace-making in East Timor, Bougainville and the Solomon Islands, supporting land based operations.

Civilian roles[]

The 2002 Maritime Forces Review identified a number of roles that other government agencies required the RNZN to undertake. Approximately 1,400 days at sea are required to fulfil these roles annually.

Roles include patrolling the exclusive economic zone, transport to offshore islands, and support for the New Zealand Customs Service.

The RNZN formerly produced hydrographic information for Land Information New Zealand under a commercial contract arrangement, however with the decommissioning of the dedicated Hydrographic survey ship HMNZS Resolution this has lapsed and the Navy now focuses on military hydrography.

Current deployments[]

Since 2001, both Anzac-class frigates have participated in the United States' Operation Enduring Freedom in the Persian Gulf and have conducted maritime patrol operations in support of American and allied efforts in Afghanistan.

On 21 June 2006 Te Mana was in South East Asia, and Te Kaha was in New Zealand waters, to be deployed to South East Asia in the second half of 2006.

Personnel[]

On 30 June 2014 the RNZN consisted of 2,050 Regular Force personnel, 392 Naval Reserve personnel.[30]

Reserves[]

Fleet Reserve[]

All regular force personnel on discharge from the RNZN are liable for service in the Royal New Zealand Navy Fleet Reserve. The Fleet reserve has an active and inactive list. RNZNVR personnel can choose to serve four years in the fleet reserve on discharge.

The RNZN has not published Fleet Reserve numbers since the early 1990s.

Volunteer Reserve[]

The primary reserve component of the RNZN is the Royal New Zealand Naval Volunteer Reserve (RNZNVR), which is organised into four units based in Auckland (with a satellite unit at Tauranga), Wellington, Christchurch, and Dunedin:

- HMNZS Ngapona: Naval Reserve, Auckland[31]

- HMNZS Olphert: Naval Reserve, Wellington[32]

- HMNZS Pegasus: Naval Reserve, Christchurch[33]

- HMNZS Toroa: Naval Reserve, Dunedin[34]

At present civilians can join the RNZNVR in one of three branches: Administration, Sea Service (for service on inshore patrol vessels), and Maritime Trade Organisation (formerly Naval Control of Shipping). In addition ex regular force personnel can now join the RNZNVR in their former branch, and depending on time out of the service, rank. The requirement to attend compulsory training one night a week has recently been removed.

Training[]

Naval Ratings begin an 18-week basic training course (Basic Common Training) prior to commencing their branch training (Basic Branch Training) which focuses on their chosen trade.

Naval Officers complete 22 weeks of training in three phases before commencing specialist training.

Finance[]

Routine funding

The RNZN is funded through a "vote" of the Parliament of New Zealand. The New Zealand Defence Force funds personnel, operating and finance costs. Funding is then allocated to specific "Output Classes", which are aligned to policy objectives.

Funding allocation in each Output Class includes consumables, personnel, depreciation and a 'Capital Charge'. The Capital Charge is a budgetary mechanism to reflect the cost of Crown capital and was set at 7.5% for the 2009/2010 year.[35]

Large projects

The Ministry of Defence is responsible for the acquisition of significant items of military equipment needed to meet New Zealand Defence Force capability requirements. Funding for the Ministry of Defence is appropriated separately.

Onshore establishments[]

[]

The Navy Museum of the Royal New Zealand Navy is located at 64 King Edward Parade, Devonport, Auckland, New Zealand [36][37] and contains important collections of naval artefacts, and extensive records.

[]

HMNZS Irirangi was a Naval Communication Station at Waiouru from 1943 to 1993.

Uniforms and insignia[]

Uniforms of the RNZN are very similar to those of the British Royal Navy and other Commonwealth of Nations navies. However, RNZN personnel wear the nationality marker "NEW ZEALAND" on a curved shoulder flash on the service uniform and embroidered on shoulder slip-ons. Also, the RNZN uses the rank of Ensign as its lowest commissioned rank.

Rank structure and insignia[]

| Rank group | General/flag officers | Field/senior officers | Junior officers | Officer cadet | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Admiral of the fleet | Vice admiral | Rear admiral | Commodore | Captain | Commander | Lieutenant commander | Lieutenant | Sub lieutenant | Ensign | Midshipman | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rank group | Senior NCOs | Junior NCOs | Enlisted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Warrant officer | Chief petty officer | Petty officer | Leading hand | Able rate | Ordinary rate | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also[]

- Military history of New Zealand

- New Zealand Sea Cadet Corps

- New Zealand military ranks

- New Zealand Defence College

- Logistics ships of the Royal New Zealand Navy

- List of individual weapons of the New Zealand armed forces

- List of ships of the Royal New Zealand Navy

References[]

- ^ Much of this discussion is taken from "RNZN History" Archived 2 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. RNZN Official Website. Accessed 15 April 2006.

- ^ https://nzhistory.govt.nz/war/royal-new-zealand-navy

- ^ McGibbon, Ian (2000). The Oxford Companion to New Zealand Military History. Auckland: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-558376-0, pp.45–46

- ^ Hensley 2009, p. 20.

- ^ The Royal New Zealand Navy, Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War, "Chapter 2: Outbreak of War: Cruise of HMS Achilles" Archived 5 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Historical Publications Branch, Wellington, 1956.

- ^ McGibbon 1981, p. 374.

- ^ https://nzhistory.govt.nz/war/royal-new-zealand-navy/second-world-war

- ^ Frame, Tom; Baker, Kevin (2000). Mutiny! Naval Insurrections in Australia and New Zealand. St. Leonards, NSW: Allen & Unwin. p. 185. ISBN 1-86508-351-8. OCLC 46882022.

- ^ Korean Scholarships – Navy Today, Defence Public Relations Unit, Issue 133, 8 June, Page 14-15

- ^ "Coalition Air Warfare in the Korean War, 1950–1953": Proceedings, Air Force Historical Foundation Symposium, Andrews AFB, Maryland, 7–8 May 2002, 142 onwards

- ^ Rear Admiral J.E.N. Welch, former Chief of Naval Staff, "The Critical Size of Our Combat Fleet," Centre for Strategic Studies New Zealand, “Papers on the Interim Report of the Defence Beyond 2000 Inquiry of the Parliamentary Select Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade: From the Seminar of New Zealand’s Defence” (Wellington: Centre for Strategic Studies, April 15, 1999).

- ^ Welch, "The Critical Size of Our Combat Fleet."

- ^ Ex RNZN Navy Club – HMNZS Canterbury 1981/82 Commission Archived 4 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Greener, Timing is everything, p. 86

- ^ Defence Force Mission In Afghanistan Archived 14 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine Updated: 24 April 2013.

- ^ "RNZN – HMNZS Resolution". RNZN Official Website.[dead link]

- ^ "New Zealand Defence Force – "Bon Voyage Wellington" – Last Visit from HMNZS Resolution". Archived from the original on 15 January 2015. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Meet The Fleet". Royal New Zealand Navy. Archived from the original on 26 August 2013. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ "RNZN – Te Kaha" Archived 19 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine. RNZN Official Website. Accessed 15 June 2014.

- ^ "RNZN – Te Mana" Archived 19 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine. RNZN Official Website. Accessed 15 June 2014.

- ^ https://navaltoday.com/2019/10/17/new-zealand-navy-retires-two-inshore-patrol-vessels/

- ^ "RNZN – Endeavour" Archived 19 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine. RNZN Official Website. Accessed 15 June 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Littoral Warfare Force". Royal New Zealand Navy. Archived from the original on 6 March 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ "Littoral Warfare Support Force". Royal New Zealand Navy. Archived from the original on 27 March 2016.

- ^ Leslie, LT CDR Trevor (March 2015). "Dive Team Bomb Disposal – doctrine explained and new equipment described" (PDF). Navy Today – official magazine of the Royal New Zealand Navy. No. 187. p. 26. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 April 2017. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- ^ "Diver". Defence Careers. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Naval Aviation Archived 21 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine. RNZAF Official Website. Accessed 15 June 2014.

- ^ "NZDF Statement of Intent" Archived 8 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine. NZDF Official Website. Accessed 28 April 2006.

- ^ "NZDF Outcomes and Objectives" Archived 11 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine. NZDF Official Website. Accessed 28 April 2006.

- ^ [1] Archived 13 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine. NZDF. Retrieved on 24 November 2015.

- ^ HMNZS Ngapona Archived 5 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine. navy.mil.nz

- ^ HMNZS Olphert Archived 5 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine. navy.mil.nz

- ^ HMNZS Pegasus Archived 5 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine. navy.mil.nz

- ^ HMNZS Toroa Archived 5 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine. navy.mil.nz

- ^ Capital Charge – Treasury Guidance — The Treasury – New Zealand Archived 2 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Treasury.govt.nz (16 December 2009). Retrieved on 2011-11-22.

- ^ "Navy Museum". Visit Us. Royal New Zealand Navy. Archived from the original on 19 December 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2012.

- ^ "Map: Naval Museum at Torpedo Bay". Google Maps. Retrieved 19 January 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Badges of Rank". nzdf.mil.nz. New Zealand Defence Force. Archived from the original on 3 July 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

Further reading[]

- Commodore J O'C Ross, The White Ensign in New Zealand

- McGibbon, Ian C. (1981). Blue-water Rationale: The naval defence of New Zealand, 1914–1942. Wellington: Government Printer. ISBN 0-477-01072-5.

- Rear-Admiral Jack Welch, "New Zealand's navy seeks 'credible minimum'", International Defence Review 9/1995, Vol. 28, No. 9, pages 75–77.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Royal New Zealand Navy. |

- Royal New Zealand Navy

- 1941 establishments in New Zealand

- Organizations established in 1941

- New Zealand Defence Force