Russian colonization of North America

It has been suggested that Russian America be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since May 2021. |

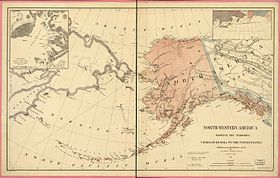

The Russian colonization of North America covers the period from 1732 to 1867, when the Russian Empire laid claim to northern Pacific Coast territories in the Americas. Russian colonial possessions in the Americas are collectively known as Russian America. Russian expansion eastward began in 1552, and in 1639 Russian explorers reached the Pacific Ocean. In 1725, Emperor Peter the Great ordered navigator Vitus Bering to explore the North Pacific for potential colonization. The Russians were primarily interested in the abundance of fur-bearing mammals on Alaska's coast, as stocks had been depleted by over hunting in Siberia. Bering's first voyage was foiled by thick fog and ice, but in 1741 a second voyage by Bering and Aleksei Chirikov made sight of the North American mainland.

Russian promyshlenniki (trappers and hunters) quickly developed the maritime fur trade, which instigated several conflicts between the Aleuts and Russians in the 1760s. The fur trade proved to be a lucrative enterprise, capturing the attention of other European nations. In response to potential competitors, the Russians extended their claims eastward from the Commander Islands to the shores of Alaska. In 1784, with encouragement from Empress Catherine the Great, explorer Grigory Shelekhov founded Russia's first permanent settlement in Alaska at Three Saints Bay. Ten years later, the first group of Orthodox Christian missionaries began to arrive, evangelizing thousands of Native Americans, many of whose descendants continue to maintain the religion.[1] By the late 1780s, trade relations had opened with the Tlingits, and in 1799 the Russian-American Company (RAC) was formed in order to monopolize the fur trade, also serving as an imperialist vehicle for the Russification of Alaska Natives.

Angered by encroachment on their land and other grievances, the indigenous peoples' relations with the Russians deteriorated. In 1802, Tlingit warriors destroyed several Russian settlements, most notably Redoubt Saint Michael (Old Sitka), leaving New Russia as the only remaining outpost on mainland Alaska. This failed to expel the Russians, who reestablished their presence two years later following the Battle of Sitka. (Peace negotiations between the Russians and Native Americans would later establish a modus vivendi, a situation that, with few interruptions, lasted for the duration of Russian presence in Alaska.) In 1808, Redoubt Saint Michael was rebuilt as New Archangel and became the capital of Russian America after the previous colonial headquarters were moved from Kodiak. A year later, the RAC began expanding its operations to more abundant sea otter grounds in Northern California, where Fort Ross was built in 1812.

By the middle of the 19th century, profits from Russia's American colonies were in steep decline. Competition with the British Hudson's Bay Company had brought the sea otter to near extinction, while the population of bears, wolves, and foxes on land was also nearing depletion. Faced with the reality of periodic Native American revolts, the political ramifications of the Crimean War, and unable to fully colonize the Americas to their satisfaction, the Russians concluded that their American colonies were too expensive to retain. Eager to release themselves of the burden, the Russians sold Fort Ross in 1842, and in 1867, after less than a month of negotiations, the United States accepted Emperor Alexander II's offer to sell Alaska. The purchase of Alaska for $7.2 million ended Imperial Russia's colonial presence in the Americas.

Exploration[]

The earliest written accounts indicate that Russians were the first Europeans to reach Alaska. There is an unofficial assumption that Slavonic navigators reached the coast of Alaska long before the 18th century.

In 1648 Semyon Dezhnev sailed from the mouth of the Kolyma River through the Arctic Ocean and around the eastern tip of Asia to the Anadyr River. One legend holds that some of his boats were carried off course and reached Alaska. However, no evidence of settlement survives. Dezhnev's discovery was never forwarded to the central government, leaving open the question of whether or not Siberia was connected to North America.

Europeans first sighted the Alaskan coastline in 1732; this sighting was made by the Russian maritime explorer and navigator Ivan Fedorov from sea near present-day Cape Prince of Wales on the eastern boundary of the Bering Strait opposite Russian Cape Dezhnev. He did not land.

The first European landfall happened in southern Alaska in 1741 during the Russian exploration by Vitus Bering and Aleksei Chirikov. In 1725, Tsar Peter the Great called for another expedition. As a part of the 1733–1743 Second Kamchatka expedition, the Sv. Petr under the Dane Vitus Bering and the Sv. Pavel under the Russian Alexei Chirikov set sail from the Kamchatkan port of Petropavlovsk in June 1741. They were soon separated, but each continued sailing east. On 15 July, Chirikov sighted land, probably the west side of Prince of Wales Island in southeast Alaska. He sent a group of men ashore in a longboat, making them the first Europeans to land on the northwestern coast of North America.On roughly 16 July, Bering and the crew of Sv. Petr sighted Mount Saint Elias on the Alaskan mainland; they turned westward toward Russia soon afterward. Meanwhile, Chirikov and the Sv. Pavel headed back to Russia in October with news of the land they had found.

Due to the distance from central authority in St. Petersburg, and combined with the difficult geography and lack of adequate resources, the next state-sponsored expedition would wait more than two decades until 1766, when captains Pyotr Krenitsyn and Mikhail Levashov embarked for the Aleutian Islands, eventually reaching their destination after initially been wrecked on Bering Island. There Bering fell ill and died, and high winds dashed the Sv. Petr to pieces. After the stranded crew wintered on the island, the survivors built a boat from the wreckage and set sail for Russia in August 1742. Bering's crew reached the shore of Kamchatka in 1742, carrying word of the expedition. The high quality of the sea-otter pelts they brought sparked Russian settlement in Alaska.

[2] Between 1774 and 1800 Spain also led several expeditions to Alaska in order to assert its claim over the Pacific Northwest. These claims were later abandoned at the turn of the 19th century following the aftermath of the Nootka Crisis. Count Nikolay Rumyantsev funded Russia's first naval circumnavigation under the joint command of Adam Johann von Krusenstern and Nikolai Rezanov in 1803–1806, and was instrumental in the outfitting of the voyage of the Riurik's circumnavigation of 1814–1816, which provided substantial scientific information on Alaska's and California's flora and fauna, and important ethnographic information on Alaskan and Californian (among other) natives.

Trading company[]

Imperial Russia was unique among European empires for having no state sponsorship of foreign expeditions or territorial (conquest) settlement. The first state-protected trading company for sponsoring such activities in the Americas was the Shelikhov-Golikov Company of Grigory Shelikhov and . A number of other companies were operating in Russian America during the 1780s. Shelikhov petitioned the government for exclusive control, but in 1788 Catherine II decided to grant his company a monopoly only over the area it had already occupied. Other traders were free to compete elsewhere. Catherine's decision was issued as the imperial ukase (proclamation) of September 28, 1788.[3]

The Shelikhov-Golikov Company formed the basis for the Russian-American Company (RAC). Its charter was laid out in a 1799, by the new Tsar Paul I, which granted the company monopolistic control over trade in the Aleutian Islands and the North America mainland, south to 55° north latitude.[4] The RAC was Russia's first joint stock company, and came under the direct authority of the Ministry of Commerce of Imperial Russia. Siberian merchants based in Irkutsk were initial major stockholders, but soon replaced by Russia's nobility and aristocracy based in Saint Petersburg. The company constructed settlements in what is today Alaska, Hawaii, and California.

Colonies[]

| Part of a series on |

| European colonization of the Americas |

|---|

|

|

|

|

The first Russian colony in Alaska was founded in 1784 by Grigory Shelikhov.[4] Subsequently, Russian explorers and settlers continued to establish trading posts in mainland Alaska, on the Aleutian Islands, Hawaii, and Northern California.

Alaska[]

The Russian-American Company was formed in 1799 with the influence of Nikolay Rezanov for the purpose of hunting sea otters for their fur.[5] The peak population of the Russian colonies was about 4,000 although almost all of these were Aleuts, Tlingits and other Native Alaskans. The number of Russians rarely exceeded 500 at any one time.[6]

California[]

The Russians established their outpost of Fort Ross in 1812 near Bodega Bay in Northern California,[7] north of San Francisco Bay. The Fort Ross colony included a sealing station on the Farallon Islands off San Francisco.[8] By 1818 Fort Ross had a population of 128, consisting of 26 Russians and of 102 Native Americans.[7] The Russians maintained it until 1841, when they left the region.[9] As of 2015 Fort Ross is a Federal National Historical Landmark on the National Register of Historic Places. It is preserved—restored in California's Fort Ross State Historic Park 50 miles north of San Francisco.[10]

Spanish concern about Russian colonial intrusion prompted the authorities in New Spain to initiate the upper Las Californias Province settlement, with presidios (forts), pueblos (towns), and the California missions. After declaring their independence in 1821 the Mexicans also asserted themselves in opposition to the Russians: the Mission San Francisco de Solano (Sonoma Mission-1823) specifically responded to the presence of the Russians at Fort Ross; and Mexico established the El Presidio Real de Sonoma or Sonoma Barracks in 1836, with General Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo as the 'Commandant of the Northern Frontier' of the Alta California Province. The fort was the northernmost Mexican outpost to halt any further Russian settlement southward. The restored Presidio and mission are in the present day city of Sonoma, California.

In 1920 a one-hundred pound bronze church bell was unearthed[by whom?] in an orange grove near Mission San Fernando Rey de España in the San Fernando Valley of Southern California. It has an inscription in the Russian language (translated here): "In the Year 1796, in the month of January, this bell was cast on the Island of Kodiak by the blessing of Juvenaly of Alaska, during the sojourn of Alexander Andreyevich Baranov." How this Russian Orthodox Kodiak church artifact from Kodiak Island in Alaska arrived at a Roman Catholic Mission Church in Southern California remains unknown.

Missionary activity[]

At Three Saints Bay, Shelekov built a school to teach the natives to read and write Russian, and introduced the first resident missionaries and clergymen who spread the Russian Orthodox faith. This faith (with its liturgies and texts, translated into Aleut at a very early stage) had been informally introduced, in the 1740s–1780s. Some fur traders founded local families or symbolically adopted Aleut trade partners as godchildren to gain their loyalty through this special personal bond. The missionaries soon opposed the exploitation of the indigenous populations, and their reports provide evidence of the violence exercised to establish colonial rule in this period.

The RAC's monopoly was continued by Emperor Alexander I in 1821, on the condition that the company would financially support missionary efforts.[11] Company board ordered chief manager Etholén to build a residency in New Archangel for bishop Veniaminov[11] When a Lutheran church was planned for the Finnish population of New Archangel, Veniamiov prohibited any Lutheran priests from proselytizing to neighboring Tlingits.[11] Veniamiov faced difficulties in exercising influence over the Tlingit people outside New Archangel, due to their political independence from the RAC leaving them less receptive to Russian cultural influences than Aleuts.[11][12] A smallpox epidemic spread throughout Alaska in 1835-1837 and the medical aid given by Veniamiov created converts to Orthodoxy.[12]

Inspired by the same pastoral theology as Bartolomé de las Casas or St. Francis Xavier, the origins of which come from early Christianity's need to adapt to the cultures of Antiquity, missionaries in Russian America applied a strategy that placed value on local cultures and encouraged indigenous leadership in parish life and missionary activity. When compared to later Protestant missionaries, the Orthodox policies "in retrospect proved to be relatively sensitive to indigenous Alaskan cultures."[11] This cultural policy was originally intended to gain the loyalty of the indigenous populations by establishing the authority of Church and State as protectors of over 10,000 inhabitants of Russian America. (The number of ethnic Russian settlers had always been less than the record 812, almost all concentrated in Sitka and Kodiak).

Difficulties arose in training Russian priests to attain fluency in any of the various Alaskan Indigenous languages. To redress this, Veniaminov opened a seminary for mixed race and native candidates for the Church in 1845.[11] Promising students were sent to additional schools in either Saint Petersburg or Irkutsk, the later city becoming the original seminary's new location in 1858.[11] The Holy Synod instructed for the opening of four missionary schools in 1841, to be located in Amlia, Chiniak, Kenai, Nushagak.[11] Veniamiov established the curriculum, which included Russian history, literacy, mathematics and religious studies.[11]

A side effect of the missionary strategy was the development of a new and autonomous form of indigenous identity. Many native traditions survived within local "Russian" Orthodox tradition and in the religious life of the villages. Part of this modern indigenous identity is an alphabet and the basis for written literature in nearly all of the ethnic-linguistic groups in the Southern half of Alaska. Father Ivan Veniaminov (later St. Innocent of Alaska), famous throughout Russian America, developed an Aleut dictionary for hundreds of language and dialect words based on the Russian alphabet.

The most visible trace of the Russian colonial period in contemporary Alaska is the nearly 90 Russian Orthodox parishes with a membership of over 20,000 men, women, and children, almost exclusively indigenous people. These include several Athabascan groups of the interior, very large Yup'ik communities, and quite nearly all of the Aleut and Alutiiq populations. Among the few Tlingit Orthodox parishes, the large group in Juneau adopted Orthodox Christianity only after the Russian colonial period, in an area where there had been no Russian settlers nor missionaries. The widespread and continuing local Russian Orthodox practices are likely the result of the syncretism of local beliefs with Christianity.

In contrast, the Spanish Roman Catholic colonial intentions, methods, and consequences in California and the Southwest were the product of the Laws of Burgos and the Indian Reductions of conversions and relocations to missions; while more force and coercion was used, the indigenous peoples likewise created a kind of Christianity that reflected many of their traditions.

Observers noted that while their religious ties were tenuous, before the sale of Alaska there were 400 native converts to Orthodoxy in New Archangel.[12] Tlingit practitioners declined in number after the lapse of Russian rule, until there were only 117 practitioners in 1882 residing in the place, by then renamed as Sitka.[12]

Russian settlements in North America[]

- Unalaska, Alaska – 1774

- Three Saints Bay, Alaska – 1784

- Fort St. George in Kasilof, Alaska – 1786

- St. Paul, Alaska – 1788

- Fort St. Nicholas in Kenai, Alaska – 1791

- Pavlovskaya, Alaska (now Kodiak) – 1791

- Fort Saints Constantine and Helen on Nuchek Island, Alaska – 1793

- Fort on Hinchinbrook Island, Alaska – 1793

- New Russia near present-day Yakutat, Alaska – 1796

- Redoubt St. Archangel Michael, Alaska near Sitka – 1799

- Novo-Arkhangelsk, Alaska (now Sitka) – 1804

- Fort Ross, California – 1812

- Fort Elizabeth near Waimea, Kaua'i, Hawai'i – 1817

- Fort Alexander near Hanalei, Kaua'i, Hawai'i – 1817

- Fort Barclay-de-Tolly near Hanalei, Kaua'i, Hawai'i – 1817

- Fort (New) Alexandrovsk at Bristol Bay, Alaska – 1819

- Redoubt St. Michael, Alaska – 1833

- Nulato, Alaska – 1834

- Redoubt St. Dionysius in present-day Wrangell, Alaska (now Fort Stikine) – 1834

- Pokrovskaya Mission, Alaska – 1837

- Kolmakov Redoubt, Alaska – 1844

Purchase of Alaska[]

By the 1860s, the Russian government was ready to abandon its Russian America colony. Zealous over-hunting had severely reduced the fur-bearing animal population, and competition from the British and Americans exacerbated the situation. This, combined with the difficulties of supplying and protecting such a distant colony, reduced interest in the territory. In addition, Russia was in a difficult financial position and feared losing Russian Alaska without compensation in some future conflict, especially to the British. The Russians believed that in a dispute with Britain, their hard-to-defend region might become a prime target for British aggression from British Columbia, and would be easily captured. So following the Union victory in the American Civil War, Tsar Alexander II instructed the Russian minister to the United States, Eduard de Stoeckl, to enter into negotiations with the United States Secretary of State William H. Seward in the beginning of March 1867. At the instigation of Seward the United States Senate approved the purchase, known as the Alaska Purchase, from the Russian Empire. The cost was set at 2 cents an acre, which came to a total of $7,200,000 on 9 April 1867. The canceled check is in the present day United States National Archives.

After Russian America was sold to the U.S. in 1867, for $7.2 million (2 cents per acre, equivalent to about $127 million in 2021 terms), all the holdings of the Russian–American Company were liquidated.

Following the transfer, many elders of the local Tlingit tribe maintained that "Castle Hill" comprised the only land that Russia was entitled to sell. Other indigenous groups also argued that they had never given up their land; the Americans encroached on it and took it over. Native land claims were not fully addressed until the latter half of the 20th century, with the signing by Congress and leaders of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act.

At the height of Russian America, the Russian population had reached 700, compared to 40,000 Aleuts. They and the Creoles, who had been guaranteed the privileges of citizens in the United States, were given the opportunity of becoming citizens within a three-year period, but few decided to exercise that option. General Jefferson C. Davis ordered the Russians out of their homes in Sitka, maintaining that the dwellings were needed for the Americans. The Russians complained of rowdiness of the American troops and assaults. Many Russians returned to Russia, while others migrated to the Pacific Northwest and California.

Legacy[]

The Soviet Union (USSR) released a series of commemorative coins in 1990 and 1991 to commemorate the 250th anniversary of the first sighting of and claiming domain over Alaska–Russian America. The commemoration consisted of a silver coin, a platinum coin and two palladium coins in both years.

At the beginning of the 21st century, a resurgence of Russian ultra nationalism has spurred regret and recrimination over the sale of Alaska to the United States.[13][14][15] There are periodic mass media stories in the Russian Federation that Alaska was not sold to the United States in the 1867 Alaska Purchase, but only leased for 99 years (= to 1966), or 150 years (= to 2017)—and will be returned to Russia.[16] However, the Alaska Purchase Treaty is absolutely clear that the agreement was for a complete Russian cession of the territory.[17]

See also[]

- Native Americans

- Juana Maria

- Peter the Aleut

- Jacob Netsvetov

- Russians

- List of Russian explorers

- Mikhail Tebenkov

- Johan Hampus Furuhjelm

- Nikolai Rezanov

- Vitus Bering

- History

- Russian Colonialism

- Territorial evolution of Russia

- Great Northern Expedition

- California Fur Rush

- Awa'uq Massacre

- Russo-American Treaty of 1824

- History of the west coast of North America

References[]

- Footnotes

- ^ Sergei., Kan (July 2014). Memory eternal : Tlingit culture and Russian Orthodox Christianity through two centuries (First paperback ed.). Seattle, Wash. ISBN 9780295805344. OCLC 901270092.

- ^ Fisher, Robin; Johnston, Hugh (1993). From Maps to Metaphors : The Pacific World of George Vancouver. British Columbia: UBC press. pp. 91–93. ISBN 9780774804707.

- ^ Pethick, Derek (1976). First Approaches to the Northwest Coast. Vancouver: J.J. Douglas. pp. 26–33. ISBN 0-88894-056-4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Black 2004, p. 102

- ^ Black 2004, p. 40

- ^ Black 2004, p. xiii

- ^ Jump up to: a b Black 2004, p. 181

- ^ Schoenherr, Allan A.; Feldmeth, C. Robert (1999). Natural History of the Islands of California. California natural history guides. 61. University of California Press. p. 375. ISBN 9780520211971. Retrieved 2015-04-27.

- ^ [1]

- ^ "Fort Ross SHP".

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Nordlander, David (1995). "Innokentii Veniaminov and the Expansion of Orthodoxy in Russian America". Pacific Historical Review. 64 (1): 19–35. doi:10.2307/3640333. JSTOR 3640333.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Kan, Sergei (1985). "Russian Orthodox Brotherhoods among the Tlingit: Missionary Goals and Native Response". Ethnohistory. 32 (3): 196–222. doi:10.2307/481921. JSTOR 481921.

- ^ Nelson, Soraya Sarhaddi (1 April 2014). "Not An April Fools' Joke: Russians Petition To Get Alaska Back". NPR. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ Tetrault-Farber, Gabrielle (31 March 2014). "After Crimea, Russians Say They Want Alaska Back". The Moscow Times. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ Gershkovich, Evan (30 March 2017). "150 Years After Sale of Alaska, Some Russians Have Second Thoughts". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ Haycox, Steve (18 May 2017). "Russian extremists want Alaska back". Anchorage Daily News. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ "Transcription of the English text of the Alaska Treaty of Cession". Our Documents. The United States National Archives. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

Further reading[]

- Black, Lydia T. (2004). Russians in Alaska, 1732–1867. Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska Press. ISBN 978-1-889963-05-1.

- Black, Lydia T.; Dauenhauer, Nora; Dauenhauer, Richard (2008). Anóoshi Lingít Aaní Ká/Russians in Tlingit America: The Battles of Sitka, 1802 and 1804. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-98601-2.

- Frost, Orcutt (2003). Bering: The Russian Discovery of America. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10059-4.

- Grinev, Andrei Valterovich (2008). The Tlingit Indians in Russian America, 1741–1867. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-2071-3.

- Miller, Gwenn A. (2010). Kodiak Kreol: Communities of Empire in Early Russian America. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4642-9.

- Oleksa, Michael J. (1992). Orthodox Alaska: A Theology of Mission. Yonkers, NY: St Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 978-0-88141-092-1.

- Oleksa, Michael J., ed. (2010). Alaskan Missionary Spirituality (2nd ed.). Yonkers, NY: St Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 978-0-88141-340-3.

- Starr, S. Frederick, ed. (1987). Russia's American Colony. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-0688-7.

- Vinkovetsky, Ilya (2011). Russian America: An Overseas Colony of a Continental Empire, 1804–1867. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539128-2.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Russian America. |

- Russian America

- Colonial United States (Russian)

- Colonization history of the United States

- European colonization of the Americas

- Subdivisions of the Russian Empire

- Fur trade

- Pre-Confederation British Columbia

- History of Yukon

- Pre-statehood history of Alaska

- Pre-statehood history of California

- History of European colonialism

- Overseas empires

- Russian exploration in the Age of Discovery

- Territorial evolution of Russia