STS-61-C

Satcom K1 is deployed from Columbia's payload bay | |

| Mission type | Satellite deployment Microgravity research |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA |

| COSPAR ID | 1986-003A |

| SATCAT no. | 16481 |

| Mission duration | 6 days, 2 hours, 3 minutes, 51 seconds |

| Distance travelled | 4,069,481 kilometers (2,528,658 mi) |

| Orbits completed | 98 |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Space Shuttle Columbia |

| Launch mass | 116,121 kilograms (256,003 lb) |

| Landing mass | 95,325 kilograms (210,156 lb) |

| Payload mass | 14,724 kilograms (32,461 lb) |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 7 |

| Members |

|

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 12 January 1986, 11:55:00 UTC |

| Launch site | Kennedy LC-39A |

| End of mission | |

| Landing date | 18 January 1986, 13:58:51 UTC |

| Landing site | Edwards |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Low Earth |

| Perigee altitude | 331 kilometres (206 mi) |

| Apogee altitude | 338 kilometres (210 mi) |

| Inclination | 28.5 degrees |

| Period | 91.2 min |

Back row L–R: Bill Nelson, Hawley, George Nelson, Front row L–R: Cenker, Bolden, Gibson, Chang-Diaz | |

STS-61-C (formerly STS-32) was the 24th mission of NASA's Space Shuttle program, and the seventh mission of Space Shuttle Columbia. It was the first time that Columbia, the first space-rated Space Shuttle orbiter to be constructed, had flown since STS-9. The mission launched from Florida's Kennedy Space Center on 12 January 1986, and landed six days later on 18 January. STS-61-C's seven-person crew included 2 future NASA Administrators: the second African-American shuttle pilot, Charles Bolden, the second sitting politician to fly in space, Representative Bill Nelson (D-FL), and the first Costa Rican-born astronaut, Franklin Chang-Diaz. It was the last shuttle mission before the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster, which occurred just ten days after STS-61-C's landing.

The STS-61-C flight has the distinction of having two members of its crew who later became NASA Administrator. (Pilot Charles Bolden served as NASA Administrator from July 17, 2009 to January 20, 2017 and Bill Nelson is the currently serving NASA Administrator.)

Crew[]

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Robert L. Gibson Second spaceflight | |

| Pilot | Charles F. Bolden First spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 1 | George D. Nelson Second spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 2 | Steven A. Hawley Second spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 3 | Franklin R. Chang-Diaz First spaceflight | |

| Payload Specialist 1 | C. William "Bill" Nelson Only spaceflight | |

| Payload Specialist 2 | Robert J. Cenker Only spaceflight | |

Backup crew[]

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Payload Specialist 2 | Gerard E. Magilton | |

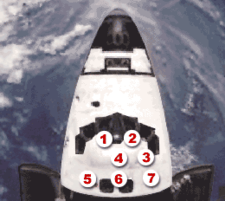

Crew seating arrangements[]

| Seat[1] | Launch | Landing |  Seats 1–4 are on the Flight Deck. Seats 5–7 are on the Middeck. |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Gibson | Gibson | |

| S2 | Bolden | Bolden | |

| S3 | G. Nelson | Chang-Diaz | |

| S4 | Hawley | Hawley | |

| S5 | Chang-Diaz | G. Nelson | |

| S6 | B. Nelson | B. Nelson | |

| S7 | Cenker | Cenker |

Mission background[]

STS-61-C saw Columbia return to flight for the first time since the STS-9 mission in November 1983, after having undergone major modifications over the course of 18 months by Rockwell International in California. Most notable of these modifications was the addition of the SILTS (Shuttle Infrared Leeside Temperature Sensing) pod atop Columbia's vertical stabilizer, which used an infrared camera to observe reentry heating on the shuttle's left wing and part of its fuselage. The camera was only used for a few more missions after STS-61-C, but the pod remained on Columbia for the remainder of its operational life. Smaller and more discreet modifications were also added at various points throughout the shuttle. The bulky ejection seats, which had been disabled after STS-4, were replaced with conventional seats and head-up displays for the commander and pilot were installed.[2]

The launch was originally scheduled for 18 December 1985, but the closeout of an aft orbiter compartment was delayed, and the mission was rescheduled for the following day. However, on 19 December, the countdown was stopped at T-14 seconds due to an out-of-tolerance turbine reading on the right SRB's hydraulic system.

Another launch attempt, on 6 January 1986, was terminated at T-31 seconds because of a problem in a valve in the liquid oxygen system. The countdown was recycled to T-20 minutes for a second launch attempt on the same day, but was held at T-9 minutes, and then scrubbed as the launch window expired.[3] Another attempt was made on 7 January, but was scrubbed because of bad weather at contingency landing sites at Dakar, Senegal, and Morón, Spain; yet another attempt, on 9 January, was delayed because of a problem with a main engine prevalve, and on 10 January, heavy rainfall in the launch area led to another scrub.

Mission summary[]

After four unsuccessful launch attempts,[4] Columbia launched successfully from Kennedy Space Center at 6:55 am EST on 12 January 1986. There were no significant anomalies reported during the launch.

The primary objective of the mission was to deploy the Satcom K1 communications satellite, second in a planned series of geosynchronous satellites owned and operated by RCA Americom; the deployment was successful. Columbia also carried a large number of small scientific experiments, including 13 Getaway Special (GAS) canisters devoted to investigations involving the effect of microgravity on materials processing, seed germination, chemical reactions, egg hatching, astronomy, atmospheric physics, and an experiment designed by Ellery Kurtz and Howard Wishnow of Vertical Horizons to determine the effects of the space environment on fine arts materials and original oil paintings, flying four of Kurtz's paintings into space. It also carried the Materials Science Laboratory-2 structure for experiments involving liquid bubble suspension by sound waves, melting and resolidification of metallic samples and container-less melting and solidification of electrically conductive specimens. Another small experiment carrier located in the payload bay was the Hitchiker G-1 (HHG-1), which carried three experiments to study film particles in the orbiter environment, test a new heat transfer system and determine the effects of contamination and atomic oxygen on ultraviolet optics materials, respectively. There were also four in-cabin experiments, three of them part of the Shuttle Student Involvement Program. The shuttle carried an experiment called the Comet Halley Active Monitoring Program (CHAMP), consisting of a 35 mm camera intended to photograph Halley's Comet through the aft flight deck overhead window. This experiment proved unsuccessful because of battery problems.

According to Bolden, in addition to deploying the RCA satellite, Cenker operated a classified experiment for the United States Air Force during the mission. Bolden was only told that it was a prototype for an infrared imaging camera.[4]

STS-61-C was originally scheduled to last seven days, but NASA decided to end it after four because its delays had delayed the next flight, STS-51-L.[4] It was rescheduled to land on 17 January, but this was brought forward by one day. However, the landing attempt on 16 January was cancelled because of unfavorable weather at Edwards Air Force Base. Continued bad weather forced another wave-off the following day. The flight was extended one more day to provide for a landing opportunity at Kennedy Space Center on 18 January – this was in order to avoid time lost in an Edwards AFB landing and turnaround. However, bad weather at the KSC landing site resulted in yet another wave-off.

Columbia finally landed at Edwards AFB on its fifth landing attempt[4] at 5:59 am PST, on 18 January. The mission lasted a total of 6 days, 2 hours, 3 minutes, and 51 seconds. STS-61-C was the last successful Space Shuttle flight before the Challenger disaster, which occurred on 28 January 1986, only 10 days after Columbia's return. Accordingly, commander Gibson later called the STS-61-C mission "The End of Innocence" for the Shuttle Program.[5]

Nelson, the Florida congressman, had hoped to receive a Florida orange after landing in the state. The personnel at Edwards greeted the crew with what Bolden described as "a peck basket of California oranges and grapefruits".[4]

Wake-up calls[]

NASA began a tradition of playing music to astronauts during the Gemini program, and first used music to wake up a flight crew during Apollo 15. Each track is specially chosen, often by the astronauts' families, and usually has a special meaning to an individual member of the crew, or is applicable to their daily activities.[6]

| Flight Day | Song | Artist/Composer |

|---|---|---|

| Day 2 | "Liberty Bell March" | John Philip Sousa |

| Day 3 | "Heart of Gold" | Neil Young |

| Day 4 | "Stars and Stripes Forever" | John Philip Sousa |

Gag photo[]

During the same session as the official crew photo, the NASA photographer took a gag photo of the STS-61-C crew with their heads and faces obscured by their helmets and visors.

See also[]

References[]

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

- ^ "STS-61C". Spacefacts. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ^ "STS-61C Press Kit" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ^ Some Trust in Chariots: The Space Shuttle Challenger Experience

- ^ a b c d e Bolden, Charles F. (6 January 2004). "Charles F. Bolden". NASA Johnson Space Center Oral History Project (Interview). Interviewed by Johnson, Sandra; Wright, Rebecca; Ross-Nazzal, Jennifer. Houston, Texas. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ^ Evans, Ben (11 January 2014). "Mission 61C: The Original 'Mission Impossible' (Part 1)". Americaspace.com. Americaspace.com. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ^ Fries, Colin (25 June 2007). "Chronology of Wakeup Calls" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 13 August 2007.

External links[]

- Space Shuttle missions

- Edwards Air Force Base

- 1986 in California

- 1986 in Florida

- Spacecraft launched in 1986

- January 1986 events

- Spacecraft which reentered in 1986