STS-80

The Wake Shield Facility takes flight for a third time, after being deployed by Columbia's Canadarm | |

| Mission type | Research |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA |

| COSPAR ID | 1996-065A |

| SATCAT no. | 24660 |

| Mission duration | 17 days, 15 hours, 53 minutes, 18 seconds |

| Distance travelled | 11,000,000 kilometres (6,800,000 mi) |

| Orbits completed | 279 |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Space Shuttle Columbia |

| Payload mass | 13,006 kilograms (28,673 lb) |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 5 |

| Members |

|

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 19 November 1996, 19:55:47 UTC |

| Launch site | Kennedy LC-39B |

| End of mission | |

| Landing date | 7 December 1996, 11:49:05 UTC |

| Landing site | Kennedy SLF (Rwy 33) |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Low Earth |

| Perigee altitude | 318 kilometres (198 mi) |

| Apogee altitude | 375 kilometres (233 mi) |

| Inclination | 28.45 degrees |

| Period | 91.5 min |

Left to right - Seated: Rominger, Cockrell; Standing: Jernigan, Musgrave, Jones | |

STS-80 was a Space Shuttle mission flown by Space Shuttle Columbia. The launch was originally scheduled for 31 October 1996, but was delayed to 19 November for several reasons.[1] Likewise, the landing, which was originally scheduled for 5 December, was pushed back to 7 December after bad weather prevented landing for two days.[2]

It was the longest Shuttle mission ever flown at 17 days, 15 hours, and 53 minutes.[2]

Although two spacewalks were planned for the mission, they were both canceled after problems with the airlock hatch prevented astronauts Tom Jones and Tammy Jernigan from exiting the orbiter.

Crew[]

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Kenneth D. Cockrell Third spaceflight | |

| Pilot | Kent V. Rominger Second spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 1 | F. Story Musgrave Sixth and last spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 2 | Thomas D. Jones Third spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 3 | Tamara E. Jernigan Fourth spaceflight | |

Crew seating arrangements[]

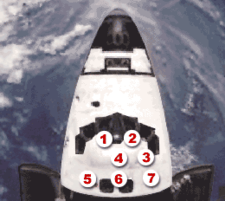

| Seat[3] | Launch | Landing |  Seats 1–4 are on the Flight Deck. Seats 5–7 are on the Middeck. |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Cockrell | Cockrell | |

| S2 | Rominger | Rominger | |

| S3 | Musgrave | Jernigan | |

| S4 | Jones | Jones | |

| S5 | Jernigan | Musgrave* |

- During landing, Musgrave remained on the flight deck in order to film the spacecraft's reentry through the overhead windows.

Mission highlights[]

- The mission deployed two satellites and successfully recovered them after they had performed their tasks.[1]

- Orbiting and Retrievable Far and Extreme Ultraviolet Spectrometer-Shuttle Pallet Satellite II (ORFEUS-SPAS II) was deployed on flight day one.[4] It was captured on flight day sixteen.[5]

- The Wake Shield Facility-3 was deployed on flight day 4, and was recaptured three days later.[1]

- The mission was the longest mission in Space Shuttle history.[6]

- On this mission, Story Musgrave became the only person to fly on all five Space Shuttles – Challenger, Atlantis, Discovery, Endeavour, and Columbia.[7]

- Musgrave also tied a record for spaceflights, and set a record for being the oldest man in space.[1] Both records have since been surpassed.[8][9]

Mission payload[]

Columbia brought with it two free floating satellites, both of which were on repeat visits to space. Also, a variety of equipment to be tested on two planned spacewalks was part of the payload. These would have been used to prepare for construction of the International Space Station. Included in the Shuttle's payload were[10]

- Orbiting and Retrievable Far and Extreme Ultraviolet Spectrometer-Shuttle Pallet Satellite II (ORFEUS-SPAS II)

- Far Ultraviolet (FUV) Spectrograph

- Extreme Ultraviolet (EUV) Spectrograph

- Interstellar Medium Absorption Profile Spectrograph (IMAPS)

- Surface Effects Sample Monitor (SESAM)

- ATV Rendezvous Pre-Development Project (ARP)

- Student Experiment on ASTRO-SPAS (SEAS)

- Wake Shield Facility (WSF-3)

- NIH-R4

- Space Experiment Module (SEM)

- EVA Development Flight Tests (EDTF-5)

- Crane

- Battery Orbital Replacement Unit

- Cable Caddy

- Portable Work Platform

- Portable Foot Restraint Work Station (PFRWS)

- Temporary Equipment Restraint Aid (TERA)

- Articulating Portable Foot Restraint

- Body Restraint Tether (BRT)

- Multi-Use Tether (MUT)

- Visualization in an Experimental Water Capillary pumped Loop (VIEW-CPL)

- Biological Research In Canister (BRIC)

- Commercial Materials Dispersion Apparatus Instrumentation Technology Associates Experiment (CCM-A) (formerly STL/NIH-C-6)

- Commercial MDA ITA Experiment (CMIX-5)

Scientific projects[]

Columbia carried into orbit two satellites that were released and recaptured after some time alone. The first was the Orbiting and Retrievable Far and Extreme Ultraviolet Spectrometer-Shuttle Pallet Satellite II (ORFEUS-SPAS II). The main component of the satellite, the ORFEUS telescope, had two spectrographs, for far and extreme ultraviolet.

Another spectrograph, the Interstellar Medium Absorption Profile Spectrograph, was also on board the satellite. Several payloads not relevant to astronomy rounded out the satellite. It performed without problems for its flight, taking 422 observations of almost 150 astronomical bodies, ranging from the moon to extra-galactic stars and a quasar. Being the second flight of ORFEUS-SPAS II allowed for more sensitive equipment, causing it to provide more than twice the data of its initial run.[1]

Also deployed from Columbia was the Wake-Shield Facility (WSF), a satellite that created an ultra-vacuum behind it, allowing for the creation of semiconductor thin films for use in advanced electronics. WSF created seven films before being recaptured by Columbia's robotic arm after three days of flight.[1] The 12-foot-diameter (3.7 m) craft was on its third mission, including STS-60, when hardware problems prevented it from deploying off the robotic arm. Wake Shield was designed and built by the Space Vacuum Epitaxy Center at the University of Houston in conjunction with its industrial partner, Space Industries, Inc.[11]

Another inclusion was a Space Experiment Module (SEM).[11] The SEM included student research projects selected to fly into space.[12] This was the first flight of the program.[13] Among the experiments conducted were analysis of bacteria growth on food in orbit, crystal growth in space, and microgravity's effect on a pendulum.[14]

NIH.R4 was an experiment conducted for the National Institute of Health and Oregon Health Sciences University.[11] It was designed to test the effects of spaceflight on circulation and vascular constriction.[15] Biological Research in Canister (BRIC) explored gravity's effects on tobacco and tomato seedlings. Visualization in an Experimental Water Capillary Pumped Loop (VIEW-CPL) was conducted to test a new idea in thermal spacecraft management.[16] The Commercial MDA ITA Experiment were a variety of experiments submitted by high school and middle school students sponsored by Information Technology Associates.[17]

Mission background[]

Astronauts were selected for the mission on 17 January 1996.[18] Stacking of the Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) began 9 September 1996.[19] On 18 September, the launch date was bumped back from no earlier than (NET) 31 October to 8 November.[20] Payload doors were closed on 25 September.[21] The following day, the External fuel tank was mated to the SRBs inside the Vehicle Assembly Building.[22]

Further progress was delayed while two windows on the orbiter were replaced; NASA feared that they might be susceptible to breakage after seven and eight flights.[23] Columbia was rolled over to the VAB on 9 October to begin final assembly preparations.[24]

On 11 October, Columbia was mated with the external fuel tank, and the payload was delivered and transferred.[25] Rollout to Pad 39B occurred on 16 October, which was followed by flight readiness checks of the main propulsion system.[26]

After a Flight Readiness Review on 28 October, an additional FRR was requested to further analyze the Redesigned Solid Rocket Motor (RSRM) due to nozzle erosion that occurred on STS-79; on the 29th, a fuel pump failed, delaying the fueling process of Columbia.[27] The erosion problem led to a week long delay instituted on 4 November.[28] A launch date of 15 November was set, contingent on a successful Atlas launch two days prior.[29] The forecast of bad weather pushed the launch back even further, to a date of 19 November.[30]

Wake-up calls[]

NASA began a tradition of playing music to astronauts during the Gemini program, which was first used to wake up a flight crew during Apollo 15.[31] Each track is specially chosen, often by their families, and usually has a special meaning to an individual member of the crew, or is applicable to their daily activities.[31][32]

| Flight Day | Song | Artist/Composer |

|---|---|---|

| Day 2 | "I Can See For Miles" | The Who |

| Day 3 | "Theme From Fireball XL5" | Barry Gray |

| Day 4 | "Roll With the Changes" | REO Speedwagon |

| Day 5 | "Reelin' and Rockin'" | Chuck Berry |

| Day 6 | "Roll with It" | Steve Winwood |

| Day 7 | "Good Times Roll" | The Cars |

| Day 8 | "Red Rubber Ball" | Cyrkle |

| Day 9 | "Alice's Restaurant" | Arlo Guthrie |

| Day 10 | "Some Guys Have All the Luck" | Robert Palmer |

| Day 11 | "Changes" | David Bowie |

| Day 12 | "Break on Through (To the Other Side)" | The Doors |

| Day 13 | "Shooting Star" | Bad Company |

| Day 14 | "Stay" | Jackson Browne |

| Day 15 | "Return to Sender" | Elvis Presley |

| Day 16 | "Should I Stay or Should I Go" | The Clash |

| Day 17 | "Nobody Does It Better" | Carly Simon |

| Day 18 | "Please Come Home for Christmas" | Sawyer Brown |

See also[]

- List of human spaceflights

- List of Space Shuttle missions

- Outline of space science

- STS-78 (16 day 21 hour Shuttle mission)

- STS-67 (16 days 15 hour Shuttle mission)

- STS-73 (15 days 21 hours Shuttle mission)

References[]

This article includes a list of general references, but it remains largely unverified because it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (May 2008) |

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "NASA – STS-80". NASA. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "STS-80 Day 19 Highlights". NASA. 7 December 1996. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ "STS-80". Spacefacts. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ^ "STS-80 Day 2 Highlights". NASA. 20 November 1996. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ "STS-80 Day 16 Highlights". NASA. 4 December 1996. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ "CNN Student News One-Sheet: Space Shuttle Facts". CNN. 11 March 2008. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ "Story Musgrave 6-time Space Shuttle Astronaut simulates Space Flight | Hubble Space Telescope | Space Exploration". Space Story. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ "STS-124 Shuttle Report | Current Space Demographic Data". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ [1]

- ^ http://science.ksc.nasa.gov/shuttle/missions/sts-80/sts-80-press-kit.txt

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "STS-80". NASA. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ "NASA – Space Experiment Module (SEM)". NASA. 8 November 2011. Archived from the original on 26 April 2010. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ Goddard News – Top Feature Archived 3 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "SEM 1 on STS-80". Musc.edu. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ "NIH.R4/STS-80". NASA. Archived from the original on 16 October 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ "KSC Fact Sheet "STS-80/Columbia – ORFEUS-SPAS-2/Wake Shield Facility-3"". NASA. Archived from the original on 17 October 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ "ITA student program". Itaspace.com. Archived from the original on 4 October 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ Jones, Thomas (2006). Sky Walking. New York, NY: HarperCollins. p. 159. ISBN 0-06-085152-X.

- ^ "10 September 1996 Shuttle Status Report". NASA. Archived from the original on 16 October 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ "18 September 1996 Shuttle Status Report". NASA. Archived from the original on 16 October 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ "25 September 1996 Shuttle Status Report". NASA. Archived from the original on 15 October 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ "26 September 1996 Shuttle Status Report". NASA. Archived from the original on 16 October 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ "4 October 1996 Shuttle Status Report". NASA. Archived from the original on 15 October 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ "10 October 1996 Shuttle Status Report". NASA. Archived from the original on 16 October 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ "11 October 1996 Shuttle Status Report". NASA. Archived from the original on 16 October 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ "16 October 1996 Shuttle Status Report". NASA. Archived from the original on 16 October 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ "29 October 1996 Shuttle Status Report". NASA. Archived from the original on 15 October 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ "4 November 1996 Shuttle Status Report". NASA. Archived from the original on 15 October 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ "12 November 1996 Shuttle Status Report". NASA. Archived from the original on 16 October 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ "14 November 1996 Shuttle Status Report". NASA. 14 November 1996. Archived from the original on 15 October 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fries, Colin (25 June 2007). "Chronology of Wakeup Calls" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 13 August 2007.

- ^

NASA (11 May 2009). "STS-80 Wakeup Calls". NASA. Missing or empty

|url=(help)

External links[]

- Space Shuttle missions

- Spacecraft launched in 1996