Hanson Formation

| Hanson Formation Stratigraphic range: Pliensbachian ~[1] | |

|---|---|

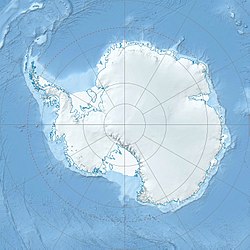

The Hanson Formation is located in the Transantarctic Mountains | |

| Type | Geological formation |

| Unit of | |

| Sub-units | Three informal members |

| Underlies | Prebble Formation |

| Overlies | Falla Formation |

| Thickness | 237.5 m (779 ft) |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Sandstone, tuffite |

| Other | Climbing-ripple lamination, horizontal lamination, and accumulations of clay-gall rip-up clasts |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 84°18′S 166°30′E / 84.3°S 166.5°ECoordinates: 84°18′S 166°30′E / 84.3°S 166.5°E |

| Approximate paleocoordinates | 57°30′S 35°30′E / 57.5°S 35.5°E |

| Region | Mount Kirkpatrick, Beardmore Glacier |

| Country | |

| Type section | |

| Named for | The Hanson Spur |

| Named by | David Elliot |

Hanson Formation (Antarctica) | |

The Hanson Formation (also known as the Shafer Peak Formation) is a geologic formation on Mount Kirkpatrick and north Victoria Land, Antarctica. It is one of the two major dinosaur-bearing rock groups found on Antarctica to date; the other is the Snow Hill Island Formation and related formations from the Late Cretaceous of the Antarctic Peninsula. The formation has yielded some Mesozoic specimens, but most of it is as yet unexcavated. Part of the of the Transantarctic Mountains, it lies below the Prebble Formation and above the Falla Formation.[2] The formation includes material from volcanic activity linked to the Karoo-Ferar eruptions of the Lower Jurassic.[3][4] The climate of the zone was similar to that of modern southern Chile, humid, with a temperature interval of 17–18 degrees.[5] The Hanson Formation is correlated with the of the Eisenhower Range and Deep Freeze Range, as well as volcanic deposits on the Convoy Range and Ricker Hills of southern Victoria Land.[2]

History[]

The Victoria Group (also called Beacon Supergroup) from the Central Transantarctic Mountains was defined by Ferrar in 1907, when he described the "Beacon Sandstone" of the sedimentary rocks in the valleys of the Victoria Land.[6] Following this initial work, the term "Beacon System" was introduced for a series of similar sandstones and associated deposits that were recovered locally.[7] Later the "Beacon Sandstone Group" was assigned to those units in Victoria Land, with Harrington in 1965 proposing the name for different units that appear in the Beacon rocks of south Victoria Land, the beds below the Maya erosion surface, the Taylor Group and the Gondwana sequence, including the Victoria Group.[8] This work left out several older units, such as the Permian coal measures and glacial deposits.[8] It was not until 1963 that there was an establishment of the Gondwana sequence: the term Falla Formation was chosen to delimit a 2300 ft (700 m) series of lower quartz sandstone, a middle mica-carbon sandstone and an upper sandstone-shale unit.[9] The formation lying above the Falla Formation and below the Prebble Formation was then termed the Upper Falla Formation, with considerable uncertainty about its age (it was calculated from the presence of Glossopteris-bearing beds (Early Permian) and the assumed possibility that the rocks were older than Dicroidium-bearing beds, thought to be Late Triassic, in the Dominion Range).[10] Later works tried to set it between the Late Triassic (Carnian) and the Lower-Middle Jurassic (Toarcian–Aalenian).[11] The local Jurassic sandstones were included in the Victoria Group, with the Beacon unit defined as a supergroup in 1972, comprising beds overlying the pre-Devonian Kukri erosion surface to the Prebble Formation in the central Transantarctic Mountains and the Mawson Formation (and its unit, then separated, the Carapace Sandstone) in southern Victoria Land.[12] The Mawson Formation, identified at the beginning as indeterminate tillite, was later placed in the Ferrar Group.[13]

Extensive fieldwork later demonstrated the need for revisions to the post-Permian stratigraphy.[14] It was found that only 282 m of the upper 500 m of the Falla Formation as delimited in 1963 correspond to the sandstone/shale sequence, with the other 200 m comprising a volcaniclastic sequence.[14] New units were then described from this location: the Fremouw Formation and Prebble Formation, the latter term being introduced for a laharic unit, not seen in 1963, that occurs between the Falla Formation and the .[14][15] A complete record was recovered at Mount Falla, revealing the sequence of events in the Transantarctic Mountains spanning the interval between the Upper Triassic Dicroidium-bearing beds and the Middle Jurassic tholeiitic lavas.[14] The upper part of the Falla Formation contains recognizable primary pyroclastic deposits, exemplified by resistant, laterally continuous silicic tuff beds, that led this to be considered a different formation, especially as it shows erosion associated with tectonic activity that preceded or accompanied the silicic volcanism and marked the onset of the development of a volcano-tectonic rift system.[2]

The Shafer Peak Formation was named from genetically identical deposits from north Victoria Land (exposed on Mt. Carson) in 2007 and correlated with the Hanson Formation, defined as tuffaceous deposits with silicic glass shards along with quartz and feldspar.[16] Later works, however, have equated it to a continuation of the Hanson Formation.[17]

The name "Hanson Formation" was proposed for the volcaniclastic sequence that was described in Barrett's 1969 Falla Formation essay.[14] The name was taken from the Hanson Spur, which lies immediately to the west of Mount Falla and is developed on the resistant tuff unit described below.[2]

Paleoenvironment[]

The Hanson Formation accumulated in a rift environment, being dominated by two types of facies: coarse- to medium-grained sandstone and tuffaceous rocks & minerals on the fluvial strata, which suggest the deposits where influenced by a large period of silicic volcanism, maybe more than 10 million years based on the thickness.[18] When looking at the composition of this tuffs, fine grain sizes, along others aspects such as bubble-wall and tricuspate shard form or crystal-poor nature trends to suggest this volcanic events developed as distal Plinian Eruptions (extremely explosive eruptions), with some concrete layers with mineral grains of bigger size showing that some sectors where more more proximal to volcanic sources.[18] The distribution of some tuffs with accretionary lapilli, found scattered geographically and stratigraphically suggest transport by ephemeral river streams, as seen in the of New Zealand.[18] The sandstones where likely derived of low-sinuosity sandybraided stream deposits, having interbeds with multistory cross-bedded sandstone bodies, indicators of either side channels or crude splay deposits and concrete well-stratified sections representing overbank deposits and/or ash recycled by ephemeral streams or aeolian processes.[18] Towards the upper layers of the formation the influence of the Tuff in the sandstones get more notorious, evidenced by bigger proportions of volcanistic minerals and ash-related materials embedded in between this layers. Overall, the unit deposition bear similarities to the several-hundredmetres-thick High Plains Cenozoic sequence of eastern Wyoming, Nebraska and South Dakota, with the fine-grained ash derived from distal volcanoes.[18]

Tectonically, based on the changues seen in the sandstone composition and the apperance of volcanic strata indicates the end of the so called foreland depositional section in the Transantarctic Mountains, while appearance of arkoses with angular detritus and common Garnet points to local Paleozoic basement uplift.[11] The Rift Valley deposition is recovered in several coeval and underliying points, with it´s thickness as indicator of palaeotopographical confinament of palaeoflows coming generally to the NW quadrant, creating a setting that received both sediment derived from the surrounding rift shoulders and ash from distal eruptions.[19] The Main fault inditacor of this rift has been alocated around the Marsh Glacier, with the so called Marsh Fault that breaks apart Precambrian rocks and the Miller Range, with other faults including a W-facing monocline that lies parallel and east of the Marsh Fault, a NW–SE-striking small graben in thec southern Marshall Mountains, the fault at the Moore Mountains, the undescribed monocline facing east in the Dominion Range and an uplifted isolated fault in the west of Coalsack Bluff.[11] Marsh Fault was likely active during the early Jurassic, leading to a development of an extensive rift valley system several thousand kilometres long along which basaltic magmatism was focused later towards the Pliensbachian, when the Hanson Formation deposited, somehow similar to East African Rift Valleys and specially Waimangu Volcanic Rift Valley, with segmentation in the rift and possible latter reverse faulting.[18]

.

Paleofauna[]

The first dinosaur to be discovered from the Hanson Formation was the predator Cryolophosaurus, in 1991; it was formally described in 1994. Alongside these dinosaur remains were fossilized trees, suggesting that plant matter had once grown on Antarctica's surface before it drifted southward. Other finds from the formation include tritylodonts, herbivorous mammal-like reptiles and crow-sized pterosaurs. Surprising was the discovery of prosauropod remains, which were found commonly on other continents only until the Early Jurassic. However, the bone fragments found in the Hanson Formation were dated to the Middle Jurassic, millions of years later. In 2004, paleontologists discovered partial remains of a large sauropod dinosaur that has not yet been formally described.

Synapsida[]

| Taxon | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indeterminate | Mt. Kirkpatrick |

An isolated upper postcanine tooth, FMNH PR1824 |

A cynodont, incertade sedis within Tritylodontidae. It is believed to be related to the Asian genus Bienotheroides.[21] Probably the largest member of the family, and among the largest post-Triassic synapsids, over 1.6 m long, it was probably as robust as a modern wolverine.[21] |

Tritylodon, example of Tritylodontidae cynodont |

Pterosauria[]

| Taxon | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indeterminate | Mt. Kirkpatrick |

Humerus |

A pterosaur. Nearly the same size as YPM Dimorphodon. Its morphotype is common for basal pterosaurs, such as those in Preondactylus or Arcticodactylus. |

Dimorphodon, an example of a dimorphodontid pterosaur |

Ornithischia[]

| Taxon | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indeterminate | Mt. Kirkpatrick |

|

A dinosaur, described as a "four or five-foot ornithischian or bird-hipped dinosaur, is on its way back to the United States in about 5,000 pounds of rock."[25] |

Eocursor, example of basal Ornithischian |

Sauropodomorpha[]

| Taxon | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glacialisaurus hammeri | Mt. Kirkpatrick |

|

A Sauropodomorph, member of the family Massospondylidae. Related to Lufengosaurus of China. |

Glacialisaurus reconstruction | |

| Indeterminate | Mt. Kirkpatrick |

|

On exhibit at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. More derived than the anchisaurian below; probably near but not in the Sauropoda.[29][30] |

||

| Indeterminate | Mt. Kirkpatrick |

|

Possible member of Anchisauria within Massopoda. On exhibit at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.[29][30] |

Inaccurate (quadrupedal) reconstruction of this species (left), along with Glacialisaurus (center) | |

| Indeterminate | Mt. Kirkpatrick |

|

A possible Pulanesaura-grade sauropod, less derived than Kotasaurus. The presence of Glacialisaurus in the Hanson Formation with advanced true sauropods shows that both basal and derived members of this lineage existed side by side in the early Jurassic.[27][31][28] |

Theropoda[]

| Taxon | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indeterminate | Mt. Kirkpatrick |

|

A theropod; previously considered Glacialisaurus remains but may instead be in a genus near Coelophysis.[33] |

FMNH PR1822, assigned to Glacialiasaurus | |

| Indeterminate | Mt. Kirkpatrick |

|

Described as "halticosaurid teeth" |

Coelophysis, an example of a coelophysid | |

| Indeterminate | Mt. Kirkpatrick |

|

Described as "dromeosaurid? teeth", it is probably either a Tachiraptor-grade averostra, a Coelophysis-like form, or possibly even a basal tetanuran |

||

| Cryolophosaurus ellioti | Mt. Kirkpatrick |

Incertade sedis within Neotheropoda, probably related to the Averostra. Initially described as a possible basal tetanuran; subsequent studies have pointed out relationships with Dilophosaurus from North America. It is the best characterized dinosaur found in the formation, and was probably the largest predator on the ecosystem.[20] |

Mounted skeleton of Cryolophosaurus |

Arthropoda[]

At southwest Gair Mesa the basal layers represent a lake shore and are characterised by the noteworthy preservation of some arthropod remains.[40]

| Taxon | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Scoyenia isp. |

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Burrows |

Burrow fossils in lacustrine environment, probably made by arthropods |

||

|

Diplichnites isp. |

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Trace fossils |

Trace fossils in lacustrine environment, probably made by arthropods (arachnids or myriapods) |

| |

|

|

Lower and Middle Hanson Formation |

Isolated valves |

A clam shrimp (“conchostracan”), member of the family . |

||

|

|

Lower and Middle Hanson Formation |

Isolated valves |

A clam shrimp (“conchostracan”), member of the family . |

||

|

|

Lower and Middle Hanson Formation |

Isolated valves |

A clam shrimp (“conchostracan”), member of the family Limnadiidae. |

||

|

Conchostraca[40] |

Indeterminate (various) |

|

Lower and Middle Hanson Formation |

Isolated valves |

Numerous conchostracan remains, found associated with lagoonar deposits and major indicators of water bodies locally along Scoyenia burrows |

|

|

Ostracoda[40] |

Indeterminate (various) |

|

Middle Hanson Formation |

Isolated valves |

Numerous ostracodan remains, found associated with lagoonar deposits and indicators of water bodies locally along Scoyenia burrows and conchostracans |

|

|

Coleoptera[40] |

Indeterminate (various) |

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Isolated elytron |

Indeterminate beetle remains |

|

|

Indeterminate |

|

Middle Hanson Formation |

Complete specimen |

Akin to the genus Periplaneta |

Flora[]

Fossilized wood is also present in the Hanson Formation, near the stratigraphic level of the tritylodont locality. It has affinities with the Araucariaceae and similar kinds of conifers.[42] In the north Victoria Land region, plant remains occur at the base of the lacustrine beds directly underlying the initial pillow lavas at the top of the sedimentary profile. Some of the layers of Shafer Peak include remains of an in situ stand gymnosperm trees:

- At Mount Carson, at least four large tree trunks were found on a exposed bedding plane. The wood is coalified and only partially silicified, with the largest stem reaching a diameter of nearly 50 cm.[40]

- In Suture Bench, silicified tree trunks are found buried in situ along lava flows. Some specimens have several holes or tunnels less than 1 cm wide that may represent arthropod borings.[40]

Palynology[]

Likely that (at least parts of) the palynomorph contents of these samples may derive from accessory clasts of underlying host strata that were incorporated and reworked during hydrovolcanic activity[43]

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Spores |

Affinities with Bryophyta. Younger index taxa (e.g., N. vallatus) are mostly absent and the proportion of Classopollis is still very high.[44] | |

|

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Spores |

Affinities with the Sphagnaceae. Sphagnum-type swamp mosses. Aquatic in temperate freshwater swamps. | |

|

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Spores |

Affinities with the Sphagnaceae. | |

|

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Spores |

Affinities with the Sphagnaceae. | |

|

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Spores |

Affinities with the family Notothyladaceae. Hornwort spores. | |

|

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Spores |

Affinities with Pleuromeiales. The Plueromeiales were tall lycophytes (2 to 6 m) common in the Triassic. These spores probably reflect a relict genus. | |

|

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Pollen |

Affinities with the family Lycopodiaceae. Absent in some samples.[44] | |

|

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Spores |

Affinities with the Calamitaceae. Horsetails, herbaceous flora characteristic of humid environments and tolerant of flooding. | |

|

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Spores |

Affinities with the Lycopodiaceae. | |

|

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Spores |

Affinities with the Selaginellaceae. | |

|

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Spores |

Affinities with the Selaginellaceae. | |

|

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Spores |

Uncertain peridophyte affinities | |

|

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Spores |

Uncertain peridophyte affinities | |

|

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Spores |

Uncertain peridophyte affinities | |

|

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Spores |

Uncertain peridophyte affinities | |

|

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Spores |

Uncertain peridophyte affinities | |

|

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Spores |

Affinities with the family Osmundaceae. Near fluvial current ferns, related to the modern Osmunda regalis. | |

|

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Spores |

Affinities with the family Osmundaceae. | |

|

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Spores |

Affinities with the family Cibotiaceae. | |

|

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Spores |

Affinities with the family Cyatheaceae or Adiantaceae. | |

|

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Spores |

Affinities with the family Schizaeaceae, Dicksoniaceae or Matoniaceae. | |

|

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Pollen |

Affinities with the Gymnospermopsida. Occasional bryophyte and lycophyte spores are found along with consistent occurrences of Podosporites variabilis.[44] | |

|

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Pollen |

Affinities with the families Caytoniaceae, Corystospermaceae, Peltaspermaceae, Umkomasiaceae and | |

|

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Pollen |

Affinities with the families Caytoniaceae, Corystospermaceae, Podocarpaceae and . | |

|

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Pollen |

Affinities with the family Caytoniaceae. | |

|

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Pollen |

Affinities with the family Araucariaceae. By the Pliensbachian, Cheirolepidiaceae reduce their abundance, with coeval proliferation of the Araucariaceae-type pollen | |

|

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Pollen |

Affinities with the family Cheirolepidiaceae. The dominance of Corollina species is the defining feature of the Corollina torosa abundance zone. | |

|

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Pollen |

Affinities with the family Cheirolepidiaceae. Most samples yield well-preserved pollen and spore assemblages strongly dominated (82% and 85%, respectively, for the two species) by Classopollis grains.[44] | |

|

|

Lower Hanson Formation |

Pollen |

Affinities with the family Cupressaceae. |

Macroflora[]

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Marchantites mawsonii |

Carapace Nunantak (reworked) |

Middle Hanson Formation |

Thalli |

A liverwort of the family Marchantiales. Reworked from the Hanson Formation to the Mawson Formation, this liverwort is related to modern humid-environment genera. |

||

|

Isoetites abundans |

Mount Carson |

Lower and Middle Hanson Formation |

Stems |

A lycophyte of the family Isoetaceae. Specimens resemble Australian ones of similar age. |

||

|

Equisetites[48] |

Indeterminate |

Mount Carson |

Lower and Middle Hanson Formation |

Fragments of rhizomes, unbranched aerial shoots, isolated leaf sheaths and nodal diaphragms |

A sphenophyte of the family Equisetaceae. Sphenophytes are common elements of Jurassic floras of southern Gondwana. |

Example of Equisetites specimen |

|

Cladophlebis oblonga |

Carapace Nunantak (reworked) Shafer Peak |

Middle Hanson Formation |

Leaves and stems |

A Polypodiopsidan of the family Osmundaceae. Reworked from the Hanson Formation to the Mawson Formation; represents fern leaves common in humid environments. |

Example of Cladophlebis specimen | |

|

Clathropteris meniscoides |

Shafer Peak Mount Carson |

Lower and Middle Hanson Formation |

Leaf segments |

A Polypodiopsidan of the family Dipteridaceae. It was the first record of the genus and species from the Antarctica. Specimens from Shafer Peak occur in a tuffitic mass-flow deposit and are associated with abundant charred wood indicating wildfires.[49] |

Example of specimen | |

|

Polyphacelus stormensis |

Mount Carson |

Lower and Middle Hanson Formation |

Leaf segments |

A Polypodiopsidan of the family Dipteridaceae. Closely related to Clathropteris meniscoides. |

||

|

cf. Matonidium goeppertii |

Mount Carson |

Lower and Middle Hanson Formation |

Pinna portions |

A Polypodiopsidan of the family Matoniaceae. |

Example of specimen | |

| Coniopteris murrayana

Coniopteris hymenophylloides |

Mount Carson |

Lower and Middle Hanson Formation |

Pinna fragments |

A Polypodiopsidan of the family Dicksoniaceae. |

Example of Coniopteris specimen | |

|

Dicroidium sp. |

Shafer Peak |

Lower and Middle Hanson Formation |

One cuticle fragment on slide |

A Pteridosperm/Seed Fern of the family Corystospermaceae. Dicroidium plants only gradually began to disappear and lingered on in Jurassic floras as minor relictual elements in more modern vegetation communities dominated by conifers, Bennettitales, and various ferns.[1] |

Example of Dicroidium specimen | |

| Otozamites linearis

Otozamites sanctae-crucis |

SW Gair Mesa

Mount Carson Shafer Peak |

Lower and Middle Hanson Formation |

Pinnately compound leaves |

A cycadophyte of the family Bennettitales. |

Example of Otozamites specimen | |

| Indeterminate | Mount Carson |

Lower and Middle Hanson Formation |

Fragment of a large, pinnately compound leaf |

A cycadophyte in the Bennettitales. |

Example of Zamites specimen | |

| Indeterminate |

Mount Carson |

Lower and Middle Hanson Formation |

Trapeziform fragment of a scale leaf |

A cycadophyte in the Bennettitales. | ||

| Indeterminate |

Mount Carson |

Lower and Middle Hanson Formation |

Cone scales |

A member of the Pinales in the Voltziales. |

||

| Indeterminate |

Mount Carson |

Lower and Middle Hanson Formation |

Cuticles |

A member of the Pinales of the family Cupressaceae. |

||

| Indeterminate |

Mount Carson |

Lower and Middle Hanson Formation |

Cuticles |

A member of the Pinales of the family Cupressaceae. |

Example of Elatocladus specimen | |

|

Indeterminate |

Carapace Nunantak (reworked)

Mount Carson |

Middle Hanson Formation |

Leaves

Cuticles |

A member of the Pinales of the family Araucariaceae. Reworked from the Hanson Formation to the Mawson Formation, representative of the presence of arboreal to arbustive flora. |

Example of Pagiophyllum specimen | |

|

Nothodacrium warrenii |

Carapace Nunantak (reworked) |

Middle Hanson Formation |

Leaves |

A member of the Pinales of the family Podocarpaceae. Reworked from the Hanson Formation to the Mawson Formation, representative of the presence of arboreal to arbustive flora. |

See also[]

- List of dinosaur-bearing rock formations

- List of fossiliferous stratigraphic units in Antarctica

- Mawson Formation

- Shafer Peak Formation

References[]

- ^ a b c Bomfleur, B.; Blomenkemper, P.; Kerp, H.; McLoughlin, S. (2018). "Polar regions of the Mesozoic–Paleogene greenhouse world as refugia for relict plant groups" (PDF). Transformative Paleobotany. 15 (1): 593–611. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d Elliot ', D.H. (1996). "The Hanson Formation: a new stratigraphical unit in the Transantarctic Mountains, Antarctica". Antarctic Science. 8 (4): 389–394. Bibcode:1996AntSc...8..389E. doi:10.1017/S0954102096000569. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ Ross, P.S.; White, J.D.L. (2006). "Debris jets in continental phreatomagmatic volcanoes: a field study of their subterranean deposits in the Coombs Hills vent complex, Antarctica". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 149 (1): 62–84. Bibcode:2006JVGR..149...62R. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2005.06.007.

- ^ Elliot, D. H.; Larsen, D. (1993). "Mesozoic volcanism in the Transantarctic Mountains: depositional environment and tectonic setting". Gondwana 8—Assembly, Evolution, and Dispersal. 1 (1): 379–410.

- ^ Chandler, M. A.; Rind, D.; Ruedy, R. (1992). "Pangaean climate during the Early Jurassic: GCM simulations and the sedimentary record of paleoclimate". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 104 (1): 543–559. Bibcode:1992GSAB..104..543C. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1992)104<0543:PCDTEJ>2.3.CO;2.

- ^ Ferrar, H.T. (1907). "Report on the field geology of the region explored during the 'Discovery' Antarctic Expedition 1901-1904". National Antarctic Expedition, Natural History. 1 (1): 1–100.

- ^ Harrington, H.J. (1958). "Nomenclature of rock units in the Ross Sea region, Antarctica". Nature. 182 (1): 290. Bibcode:1958Natur.182..290H. doi:10.1038/182290a0. S2CID 4249714. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ a b Harrington, H.J. (1965). "Geology and morphology of Antarctica". Ivan Oye, P. & van Mieohem, J, Eds. Biogeography and Ecology of Antarctica. Monographiae Biologicae. 15 (1): 1–71.

- ^ Grindley, G.W. (1963). "The geology of the Queen Alexandra Range, Beardmore Glacier, Ross Dependency, Antarctica; with notes on the correlation of Gondwana sequences". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 6 (1–2): 307–347. doi:10.1080/00288306.1963.10422067.

- ^ Barret, P.J. (1969). "Stratigraphy and petrology of the mainly fluviatile Permian and Triassic Beacon rocks, Beardmore Glacier area, Antarctica". Institute of Polar Studies, Ohio State University. 34 (2–3): 132.

- ^ a b c Collinston, J.W.; Isbell, J.L.; Elliot, D.H.; Miller, M.F.; Miller, J.W.G. (1994). "Permian-TriassicTransantarctic basin". Memoir of the Geological Society of America. 184 (1): 173–222. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ Barret, P.J.; Elliot, D.H. (1972). "The early Mesozoic volcaniclastic Prebble Formation, Beardmore Glacier area". In ADIE, R.J., Ed.Antarctic Geology and Geophysics: 403–409.

- ^ Ballance, P.F.; Watters, W.A. (1971). "The Mawson Diamictite and the Carapace Sandstone, formations of the Ferrar Group at Allan Hills and Carapace Nunatak, Victoria Land, Antarctica". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 14 (1): 512–527. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Barret, P.J.; Elliot, D.H.; Lindsay, J.F. (1986). "The Beacon Supergroup (Devonian-Triassic) and Ferrar Group (Jurassic) in the Beardmore Glacier area, Antarctica". Antarctic Research Series. 36 (1): 339–428. doi:10.1029/AR036p0339.

- ^ Barret, P.J.; Elliot, D.H. (1973). "Reconnaissance Geologic Map of the Buckley Island Quadrangle, Transantarctic Mountains, Antarctica". US Geological Survey, Antarctica. 1 (1): 1–42. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ Schöner, R.; Viereck-Goette, L.; Schneider, J.; Bomfleur, B. (2007). "Triassic-Jurassic sediments and multiple volcanic events in North Victoria Land, Antarctica: A revised stratigraphic model". In Antarctica: A Keystone in a Changing World–Online Proceedings of the 10th ISAES, Edited by AK Cooper and CR Raymond et Al., USGS Open-File Report. Open-File Report. 1047 (1): 1–5. doi:10.3133/ofr20071047SRP102.

- ^ Bomfleur, B.; Mörs, T.; Unverfärth, J.; Liu, F.; Läufer, A.; Castillo, P.; Crispini, L. (2021). "Uncharted Permian to Jurassic continental deposits in the far north of Victoria Land, East Antarctica". Journal of the Geological Society. 178 (1). doi:10.1144/jgs2020-062. S2CID 226380284. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Elliot, D. H.; Larsen, D.; Fanning, C. M.; Fleming, T. H.; Vervoort, J. D. (2017). "The Lower Jurassic Hanson Formation of the Transantarctic Mountains: implications for the Antarctic sector of the Gondwana plate margin" (PDF). Geological Magazine. 154 (4): 777–803. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ Elliot, D. H. (2000). "Stratigraphy of Jurassic pyroclastic rocks in the Transantarctic Mountains". Journal of African Earth Sciences. 31 (1): 77–89. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Weishampel, David B; et al. (2004). "Dinosaur distribution (Early Jurassic, Asia)." In: Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. p.537. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- ^ a b c Hammer, W.R.; Smith, N.D. (2008). "A tritylodont postcanine from the Hanson Formation of Antarctica". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28 (1): 269–273. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2008)28[269:ATPFTH]2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Stilwell, Jeffrey; Long, John (2011). Frozen in Time –prehistoric life of Antarctica (1 ed.). Melbourne, Australia: CSIRO Publishing. pp. 1–200. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ a b Hammer, W. R.; Hickerson, W. J. (1996). "Implications of an Early Jurassic vertebrate fauna from Antarctica". The Continental Jurassic. Museum of Northern Arizona Bulletin. 60 (1): 215–218.

- ^ Niiler, E. "Primitive Dinosaur Found in Antarctic Mountains". nbcnews. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ a b c College, Augustana. "Hammer adds another new dinosaur to his collection". Augustana College. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d Museum, Field (June 2011). "Surprising Discoveries - Antarctica Video Report #12". Vimeo. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Smith, Nathan D.; Pol, Diego (2007). "Anatomy of a basal sauropodomorph dinosaur from the Early Jurassic Hanson Formation of Antarctica" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 52 (4): 657–674.

- ^ a b Smith, N.D., Makovicky, P.J., Pol, D., Hammer, W.R., and Currie, P.J. (2007). "The Dinosaurs of the Early Jurassic Hanson Formation of the Central Transantarctic Mountains: Phylogenetic Review and Synthesis" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey and the National Academies. 2007 (1047srp003): 5 pp. doi:10.3133/of2007-1047.srp003.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Smith, Nathan D. (2013). "New Dinosaurs from the Early Jurassic Hanson Formation of Antarctica, and Patters of Diversity and Biogeography in Early Jurassic Sauropodomorphs". Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. 45 (7): 897.

- ^ a b c NHM. "Antarctic Dinosaurs, Discover new species of dinosaurs as you follow in the steps of Antarctic adventurer-scientists". Natural History Museum of Los Angeles. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ a b Pickrell, John (2004). "Two New Dinosaurs Discovered in Antarctica". National Geographic. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ Joyce, C. "Digging for dinosaurs in Antarctica: Giant bones suggest icy continent had warmer past". NPR.org. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ a b Carrano, M. T. (2020). Taxonomic opinions on the Dinosauria.

- ^ a b Ford, T. "Small theropods". Dinosaur Mailing List. Cleveland Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ a b Vega, G. C.; Olalla-Tárraga, M. Á. (2020). "Past changes on fauna and flora distribution. In Past Antarctica". Academic Press. 245: 165–179.

- ^ Hammersue, William R.; Hickerson, William J. (1994). "A Crested Theropod Dinosaur from Antarctica". Science. 264 (5160): 828–830. Bibcode:1994Sci...264..828H. doi:10.1126/science.264.5160.828. PMID 17794724. S2CID 38933265. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ "Table 4.1," in Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 74.

- ^ "New Information on the Theropod Dinosaur Cryolophosaurus Ellioti from the Early Jurassic Hanson Formation Of The Central Transantarctic Mountains". SVP Conference Abstracts 2017: 196. 2017.

- ^ Smith, N.D; Makovicky, P.J.; Hammer, W.R.; Currie, P.J. (2007). "Osteology of Cryolophosaurus ellioti (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Early Jurassic of Antarctica and implications for early theropod evolution". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 151 (2): 377–421. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2007.00325.x.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Bomfleur, B.; Schneider, J. W.; Schöner, R.; Viereck-Götte, L.; Kerp, H. (2011). "Fossil sites in the continental Victoria and Ferrar groups (Triassic-Jurassic) of north Victoria Land, Antarctica". Polarforschung. 80 (2): 88–99. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Tasch, P. (1984). "Biostratigraphy and palaeontology of some conchostracan-bearing beds in southern Africa". Palaeontologia Africana. 25 (1): 61–85. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ Gair, H. S.; Norris, G.; Ricker, J. (1965). "Early mesozoic microfloras from Antarctica". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 8 (2): 231–235. doi:10.1080/00288306.1965.10428109.

- ^ Bomfleur, B.; Schöner, R.; Schneider, J. W.; Viereck, L.; Kerp, H.; McKellar, J. L. (2014). "From the Transantarctic Basin to the Ferrar Large Igneous Province—new palynostratigraphic age constraints for Triassic–Jurassic sedimentation and magmatism in East Antarctica". Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 207 (1): 18–37. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Unverfärth, J.; Mörs, T.; Bomfleur, B. (2020). "Palynological evidence supporting widespread synchronicity of Early Jurassic silicic volcanism throughout the Transantarctic Basin". Antarctic Science. 32 (5): 396–397. Bibcode:2020AntSc..32..396U. doi:10.1017/S0954102020000346. S2CID 224858807. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Musumeci, G.; Pertusati, P. C.; Ribecai, C.; Meccheri, M. (2006). "Early Jurassic fossiliferous black shales in the Exposure Hill Formation, Ferrar Group of northern Victoria Land, Antarctica". Terra Antartica Reports. 12 (1): 91–98. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d Cantrill, D. J.; Hunter, M. A. (2005). "Macrofossil floras of the Latady Basin, Antarctic Peninsula". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 48 (3): 537–553. doi:10.1080/00288306.2005.9515132. S2CID 129854482. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d Cantrill, D. J.; Poole, I. (2012). "The vegetation of Antarctica through geological time". Cambridge University Press. 1 (1): 1–340. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139024990. ISBN 9781139024990. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

{{cite journal}}: External link in|ref= - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Bomfleur, B.; Pott, C.; Kerp, H. (2011). "Plant assemblages from the Shafer Peak Formation (Lower Jurassic), north Victoria Land, Transantarctic Mountains". Antarctic Science. 23 (2): 188–208. Bibcode:2011AntSc..23..188B. doi:10.1017/S0954102010000866. S2CID 130084588.

- ^ a b c Bomfleur, B.; Kerp, H. (2010). "The first record of the dipterid fern leaf Clathropteris Brongniart from Antarctica and its relation to Polyphacelus stormensis Yao, Taylor et Taylor nov. emend". Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 160 (3–4): 143–153. doi:10.1016/j.revpalbo.2010.02.003. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- Geologic formations of Antarctica

- Jurassic System of Antarctica

- Hettangian Stage

- Pliensbachian Stage

- Sinemurian Stage

- Sandstone formations

- Tuff formations

- Fluvial deposits

- Paleontology in Antarctica

- Landforms of the Ross Dependency