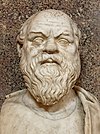

Socrate

Socrate is a work for voice and piano (or small orchestra) by Erik Satie. First published in 1919 for voice and piano, in 1920 a different publisher reissued the piece "revised and corrected".[1] A third version of the work exists, for small orchestra and voice, for which the manuscript has disappeared and which is available now only in print. The text is composed of excerpts of Victor Cousin's translation of Plato's dialogues, all of the chosen texts referring to Socrates.

Commission – composition[]

The work was commissioned by Princess Edmond de Polignac in October 1916. The Princess had specified that female voices should be used: originally the idea had been that Satie would write incidental music to a performance where the Princess and/or some of her (female) friends would read aloud texts of the ancient Greek philosophers. As Satie, after all, was not so much in favour of melodrama-like settings, that idea was abandoned, and the text would be sung — be it in a more or less reciting way. However, the specification remained that only female voices could be used (for texts of dialogues that were supposed to have taken place between men).

Satie composed Socrate between January 1917 and the spring of 1918, with a revision of the orchestral score in October of that same year. During the first months he was working on the composition, he called it Vie de Socrate. In 1917 Satie was hampered by a lawsuit over an insulting postcard he had sent, which nearly resulted in prison time. The Princess diverted this danger by her financial intercession in the first months of 1918, after which Satie could work free of fear.

The musical form[]

Satie presents Socrate as a "symphonic drama in three parts". "Symphonic drama" appears to allude to Romeo et Juliette, a "dramatic symphony" that Hector Berlioz had written nearly eighty years earlier: and as usual, when Satie makes such allusions, the result is about the complete reversal of the former example. Where Berlioz's symphony is more than an hour and a half of expressionistic, heavily orchestrated drama, an opera forced into the form of a symphony, Satie's thirty-minute composition reveals little drama in the music: the drama is entirely concentrated in the text, which is presented in the form of recitativo-style singing to a background of sparsely orchestrated, nearly repetitive music, picturing some aspects of Socrates' life, including his final moments.

As Satie apparently did not foresee an enacted or scenic representation, and also while he disconnected the male roles (according to the text) from the female voice(s) delivering these texts, keeping in mind a good understandability of the story exclusively by the words of the text, the form of the composition could rather be considered as (secular) oratorio, than opera, or (melo)drama (or symphony).

It is possible to think that Satie took formally similar secular cantatas for one or two voices and a moderate accompaniment as his examples for the musical form of Socrate: nearly all Italian and German Baroque composers had written such small-scale cantatas, generally on an Italian text: Vivaldi (RV 649–686), Handel (HWV 77–177), Bach (BWV 203, 209), etc. This link is however unlikely: these older compositions all alternated recitatives with arias, further there is very little evidence Satie ever based his work directly on the examples of foreign baroque composers, and most of all, as far as the baroque composers were known in early 20th century Paris, these small secular Italian cantatas would be the least remembered works of any of these composers.

The three parts of the composition are:

- Portrait de Socrate ("Portrait of Socrates"), text taken from Plato's Symposium

- Les bords de l'Ilissus ("The banks of the Ilissus"), text taken from Plato's Phaedrus

- Mort de Socrate ("Death of Socrates"), text taken from Plato's Phaedo

The music[]

The piece is written for voice and orchestra, but also exists in a version for voice and piano. This reduction had been produced by Satie, concurrently with the orchestral version.

Each speaker in the various sections is meant to be represented by a different singer (Alcibiades, Socrates, Phaedrus, Phaedo), according to Satie's indication two of these voices soprano, the two other mezzo-sopranos.

Nonetheless all parts are more or less in the same range, and the work can easily be sung by a single voice, and has often been performed and recorded by a single vocalist, female as well as male. Such single vocalist performances diminish however the effect of dialogue (at least in the two first parts of the symphonic drama – in the third part there is only Phaedo telling the story of Socrates' death).

The music is characterised by simple repetitive rhythms, parallel cadences, and long ostinati.

The text[]

Although more recent translations were available, Satie preferred Victor Cousin's then antiquated French translation of Plato's texts: he found in them more clarity, simplicity and beauty.

The translation of the libretto of Socrate that follows is taken from Benjamin Jowett's translations of Plato's dialogues that can be found on the Gutenberg Project website. The original French text can be found here.

Part I – Portrait of Socrates[]

[From Symposium, 215a-e, 222e]

- Alcibiades

- And now, my boys, I shall praise Socrates in a figure which will appear to him to be a caricature, and yet I speak, not to make fun of him, but only for the truth's sake. I say, that he is exactly like the busts of Silenus, which are set up in the statuaries' shops, holding pipes and flutes in their mouths; and they are made to open in the middle, and have images of gods inside them. I say also that he is like Marsyas the satyr. [...] And are you not a flute-player? That you are, and a performer far more wonderful than Marsyas. He indeed with instruments used to charm the souls of men by the power of his breath, and the players of his music do so still: for the melodies of Olympus are derived from Marsyas who taught them [...] But you produce the same effect with your words only, and do not require the flute: that is the difference between you and him. [...] And if I were not afraid that you would think me hopelessly drunk, I would have sworn as well as spoken to the influence which they have always had and still have over me. For my heart leaps within me more than that of any Corybantian reveller, and my eyes rain tears when I hear them. And I observe that many others are affected in the same manner. [...] And this is what I and many others have suffered from the flute-playing of this satyr.

- Socrates

- [...] you praised me, and I in turn ought to praise my neighbour on the right [...]

Part II – On the banks of the Ilissus[]

[From Phaedrus, 229a-230c]

- Socrates

- Let us turn aside and go by the Ilissus; we will sit down at some quiet spot.

- Phaedrus

- I am fortunate in not having my sandals, and as you never have any, I think that we may go along the brook and cool our feet in the water; this will be the easiest way, and at midday and in the summer is far from being unpleasant.

- Socrates

- Lead on, and look out for a place in which we can sit down.

- Phaedrus

- Do you see the tallest plane-tree in the distance?

- Socrates

- Yes.

- Phaedrus

- There are shade and gentle breezes, and grass on which we may either sit or lie down.

- Socrates

- Move forward.

- Phaedrus

- I should like to know, Socrates, whether the place is not somewhere here at which Boreas is said to have carried off Orithyia from the banks of the Ilissus?

- Socrates

- Such is the tradition.

- Phaedrus

- And is this the exact spot? The little stream is delightfully clear and bright; I can fancy that there might be maidens playing near.

- Socrates

- I believe that the spot is not exactly here, but about a quarter of a mile lower down, where you cross to the temple of Artemis, and there is, I think, some sort of an altar of Boreas at the place.

- Phaedrus

- I have never noticed it; but I beseech you to tell me, Socrates, do you believe this tale?

- Socrates

- The wise are doubtful, and I should not be singular if, like them, I too doubted. I might have a rational explanation that Orithyia was playing with Pharmacia, when a northern gust carried her over the neighbouring rocks; and this being the manner of her death, she was said to have been carried away by Boreas. [...] according to another version of the story she was taken from Areopagus, and not from this place. [...] But let me ask you, friend: have we not reached the plane-tree to which you were conducting us?

- Phaedrus

- Yes, this is the tree.

- Socrates

- By Here, a fair resting-place, full of summer sounds and scents. Here is this lofty and spreading plane-tree, and the agnus castus high and clustering, in the fullest blossom and the greatest fragrance; and the stream which flows beneath the plane-tree is deliciously cold to the feet. Judging from the ornaments and images, this must be a spot sacred to Achelous and the Nymphs. How delightful is the breeze:--so very sweet; and there is a sound in the air shrill and summerlike which makes answer to the chorus of the cicadae. But the greatest charm of all is the grass, like a pillow gently sloping to the head. My dear Phaedrus, you have been an admirable guide.

Part III – Death of Socrates[]

[From Phaedo, 3–33–35–38–65–66-67]

- Phaedo

- As [...] Socrates lay in prison [...] we had been in the habit of assembling early in the morning at the court in which the trial took place, and which is not far from the prison. There we used to wait talking with one another until the opening of the doors (for they were not opened very early); then we went in and generally passed the day with Socrates. [...] On our arrival the jailer who answered the door, instead of admitting us, came out and told us to stay until he called us. [...] He soon returned and said that we might come in. On entering we found Socrates just released from chains, and Xanthippe, whom you know, sitting by him, and holding his child in her arms. [...] Socrates, sitting up on the couch, bent and rubbed his leg, saying, as he was rubbing: "How singular is the thing called pleasure, and how curiously related to pain, which might be thought to be the opposite of it; [...] Why, because each pleasure and pain is a sort of nail which nails and rivets the soul to the body [...] I am not very likely to persuade other men that I do not regard my present situation as a misfortune, if I cannot even persuade you that I am no worse off now than at any other time in my life. Will you not allow that I have as much of the spirit of prophecy in me as the swans? For they, when they perceive that they must die, having sung all their life long, do then sing more lustily than ever, rejoicing in the thought that they are about to go away to the god whose ministers they are." [...]

- Often, [...] I have wondered at Socrates, but never more than on that occasion. [...] I was close to him on his right hand, seated on a sort of stool, and he on a couch which was a good deal higher. He stroked my head, and pressed the hair upon my neck—he had a way of playing with my hair; and then he said: "To-morrow, Phaedo, I suppose that these fair locks of yours will be severed." [...] When he had spoken these words, he arose and went into a chamber to bathe; Crito followed him and told us to wait. [...] When he came out, he sat down with us again after his bath, but not much was said. Soon the jailer, who was the servant of the Eleven, entered and stood by him, saying: "To you, Socrates, whom I know to be the noblest and gentlest and best of all who ever came to this place, I will not impute the angry feelings of other men, who rage and swear at me, when, in obedience to the authorities, I bid them drink the poison—indeed, I am sure that you will not be angry with me; for others, as you are aware, and not I, are to blame. And so fare you well, and try to bear lightly what must needs be—you know my errand." Then bursting into tears he turned away and went out. Socrates looked at him and said: "I return your good wishes, and will do as you bid." Then turning to us, he said: "How charming the man is: since I have been in prison he has always been coming to see me, and at times he would talk to me, and was as good to me as could be, and now see how generously he sorrows on my account. We must do as he says, Crito; and therefore let the cup be brought, if the poison is prepared: if not, let the attendant prepare some." [...]

- Crito made a sign to the servant, who was standing by; and he went out, and having been absent for some time, returned with the jailer carrying the cup of poison. Socrates said: "You, my good friend, who are experienced in these matters, shall give me directions how I am to proceed." The man answered: "You have only to walk about until your legs are heavy, and then to lie down, and the poison will act." At the same time he handed the cup to Socrates [...] Then raising the cup to his lips, quite readily and cheerfully he drank off the poison. And hitherto most of us had been able to control our sorrow; but now when we saw him drinking, and saw too that he had finished the draught, we could no longer forbear, and in spite of myself my own tears were flowing fast; so that I covered my face and wept, not for him, but at the thought of my own calamity in having to part from such a friend. [...] and he walked about until, as he said, his legs began to fail, and then he lay on his back, according to the directions, and the man who gave him the poison now and then looked at his feet and legs; and after a while he pressed his foot hard, and asked him if he could feel; and he said: "No"; and then his leg, and so upwards and upwards, and showed us that he was cold and stiff. And he felt them himself, and said: "When the poison reaches the heart, that will be the end." He was beginning to grow cold about the groin, when he uncovered his face, for he had covered himself up, and said—they were his last words—he said: "Crito, I owe a cock to Asclepius; will you remember to pay the debt?" [...] in a minute or two a movement was heard, and the attendants uncovered him; his eyes were set, and Crito closed his eyes and mouth. Such was the end, Echecrates, of our friend; concerning whom I may truly say, that of all the men of his time whom I have known, he was the wisest and justest and best.

Whiteness[]

Satie described he meant Socrate to be white, and mentions to his friends that for achieving that whiteness, he gets himself into the right mood by eating nothing other than "white" foods. He wants Socrate to be transparent, lucid, and unimpassioned – not so surprising as counter-reaction to the turmoil that came over him for writing an offensive postcard. He also appreciated the fragile humanity of the ancient Greek philosophers to which he was devoting his music.[2]

Reception history[]

Some critics characterized the work as dull or featureless – others find in it an almost superhuman tranquility and delicate beauty.[citation needed]

First performances[]

The first (private) performance of parts of the work had taken place in April 1918 with the composer at the piano and Jane Bathori singing (all the parts), in the salons of the Princess de Polignac.

Several more performances of the piano version were held, public as well as private, amongst others André Gide, James Joyce and Paul Valéry attending.

The vocal score (this is the piano version) was available in print from the end of 1919 on. It is said Gertrude Stein became an admirer of Satie hearing Virgil Thomson perform the Socrate music on his piano.

In June 1920 the first public performance of the orchestral version was presented. The public thought it was hearing a new musical joke by Satie, and laughed – Satie felt misunderstood by that behavior.

The orchestral version was not printed until several decades after Satie's death.

Reception in music, theatre and art history[]

In 1936 Virgil Thomson asked Alexander Calder to create a stage set for Socrate. New York Times critic Robert Shattuck described the 1977 National Tribute to Alexander Calder performance, “I have always gone away with the feeling that Socrate creates a large space that it does not itself completely fill… Here, of course, is where Calder comes in: He was commissioned to do sets for Socrate in 1936.”[3] In 1936 the American premiere of Socrate, with a mobile set by Alexander Calder was held at the Wadsworth Atheneum.[4] The work then traveled to the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center for the opening week of the FAC.[5]

John Cage transcribed the music of Socrate for two pianos in 1944 for Merce Cunningham's dance, titled . A later dance, Second Hand, was also based on Satie's Socrate. When in 1969 Éditions Max Eschig refused performing rights, Cage made Cheap Imitation, based on an identical rhythmic structure. In 2015, ninety years after Satie's death, Cage's 1944 setting was performed by Alexander Lubimov and Slava Poprugin[6] for the CD Paris joyeux & triste.

The Belgian painter Jan Cox (1919–1980) made two paintings on the theme of the death of Socrates (1952 and 1979, a year before his suicide), both paintings referring to Satie's Socrate: pieces of the printed score of Satie's Socrate were glued on one of these paintings; the other has quotes of Cousin's translation of Plato on the frame.

Mark Morris created a dance in 1983 to the third section of Socrate, The Death of Socrates with a set design by Robert Bordo. Morris later choreographed the entire work, which premiered in 2010 (costume design by Martin Pakledinaz, lighting design and decor by Michael Chybowski).

Recordings[]

- This (abandoned) webpage gives an overview of recordings of Socrate up to the early 21st century: https://web.archive.org/web/20050406001920/http://hem.passagen.se/satie/db/socrate.htm

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Wolfgang Rathert and Andreas Traub, "Zu einer bislang unbekannten Ausgabe des 'Socrate' von Erik Satie", in Die Musikforschung, Jg. 38 (1985), booklet 2, p. 118–121.

- ^ Volta 1989.

- ^ https://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9E07E5D61F31E135A25755C0A9679D946690D6CF

- ^ http://thewadsworth.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/wama_firsts_november2014.pdf

- ^ http://www.csfineartscenter.org/about/history/birth-of-the-colorado-springs-fine-arts-center/

- ^ Slava Poprugin on Royal Conservatoire The Hague

- Dorf, Samuel. "Étrange n’est-ce pas? The Princesse Edmond de Polignac, Erik Satie’s Socrate, and a Lesbian Aesthetic of Music?” French Literature Series 34 (2007): 87–99.

- Alan M. Gillmor, Erik Satie. Twayne Pub., 1988, reissued 1992 – ISBN 0-393-30810-3, 387pp.

- Ornella Volta, translated by Todd Niquette, Give a dog a bone: Some investigations into Erik Satie (Original title: Le rideau se leve sur un os – Revue International de la Musique Francaise, Vol. 8, No. 23, 1987)

- Volta, Ornella (1989). "Socrate". Satie Seen Through His Letters. Translated by Bullock, Michael. Marion Boyars. ISBN 071452980X.

- Compositions by Erik Satie

- Oratorios

- 1919 compositions

- Cultural depictions of Socrates