Halcyon (dialogue)

| Part of a series on |

| Platonism |

|---|

|

| The dialogues of Plato |

|

| Allegories and metaphors |

| Related articles |

| Related categories |

|

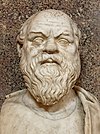

Plato |

|

Halcyon (Greek: Ἀλκυών) is a short dialogue attributed in the manuscripts to both Plato and Lucian, although the work is not by either writer.[1] Favorinus, writing in the early second century, attributes it to a certain Leon.[2] as did Nicias of Nicaea. [3]

Content[]

In the dialogue, Socrates relates to Chaerephon the ancient myth of Halcyon, a woman who was transformed by the gods into a bird in order to be able to search the seas for her husband Ceyx, who was lost at sea. Skeptical of this account, Chaerephon questions the possibility that humans can be transformed into birds. In response, Socrates cautions that there are many amazing things unknown, or at least not fully understood by humans, and advocates epistemological humility for mortals in light of the gods' abilities—or, more generally, in light of that which humans do not now know. For comparison, Socrates refers to a bad storm which recently took place, and which was immediately followed by a sudden calm; such a sudden transformation is all at once amazing, real, and beyond the power of humans to effect. He also points out the vast differences in strength and intelligence between adults and children, with the latter often being incapable of comprehending what adults can do. Both analogies taken together support the possibility that the gods may indeed have the ability to transform humans into birds, which process is simply not understood by humans, as opposed to being impossible. Socrates concludes by resolving to pass the myth down to his children as it was communicated to him, and especially with the hope that it will inspire his wives Xanthippe and Myrto to remain devoted to him. As is stated at its conclusion, the conversation is conducted in the port of Phaleron, also the narrative setting of Plato's Symposium.

The text was included in the first century Platonic canon of Thrasyllus of Mendes, but had been expunged prior to the Stephanus pagination and is thus rarely found in modern collections of Plato, although it appears in Hackett's Complete Works. It is often still included among the spurious works of Lucian.[4]

Texts and translations[]

- Macleod, M. D., Lucian, Vol. VIII (Harvard University Press, 1967). ISBN 978-0-674-99476-8 (Greek and English)

- Stief, Jake E., Halcyon (Stief Books, 2018). ASIN B07DMRR5VJ (English)

Notes[]

- Dialogues of Plato

- Works by Lucian

- Greek mythology stubs