Timaeus (dialogue)

| Part of a series on |

| Platonism |

|---|

|

| The dialogues of Plato |

|

| Allegories and metaphors |

| Related articles |

| Related categories |

|

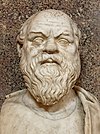

Plato |

|

Timaeus (/taɪˈmiːəs/; Greek: Τίμαιος, translit. Timaios, pronounced [tǐːmai̯os]) is one of Plato's dialogues, mostly in the form of a long monologue given by the title character Timaeus of Locri, written c. 360 BC. The work puts forward speculation on the nature of the physical world and human beings and is followed by the dialogue Critias.

Participants in the dialogue include Socrates, Timaeus, Hermocrates, and Critias. Some scholars believe that it is not the Critias of the Thirty Tyrants who appears in this dialogue, but his grandfather, who is also named Critias.[1][2][3] It has been suggested from some traditions (Diogenes Laertius (VIII 85) from Hermippus (3rd century BC) and Timon (c. 320 – c. 230 BC)) that Timaeus was influenced by a book about Pythagoras, written by Philolaus, although this assertion is generally considered false.[4]

Introduction[]

The dialogue takes place the day after Socrates described his ideal state. In Plato's works such a discussion occurs in the Republic. Socrates feels that his description of the ideal state wasn't sufficient for the purposes of entertainment and that "I would be glad to hear some account of it engaging in transactions with other states" (19b).

Hermocrates wishes to oblige Socrates and mentions that Critias knows just the account (20b) to do so. Critias proceeds to tell the story of Solon's journey to Egypt where he hears the story of Atlantis, and how Athens used to be an ideal state that subsequently waged war against Atlantis (25a). Critias believes that he is getting ahead of himself, and mentions that Timaeus will tell part of the account from the origin of the universe to man.

Critias also cites the Egyptian priest in Sais about long-term factors on the fate of mankind:

"There have been, and will be again, many destructions of mankind arising out of many causes; the greatest have been brought about by the agencies of fire and water, and other lesser ones by innumerable other causes. There is a story that even you [Greeks] have preserved, that once upon a time, Phaethon, the son of Helios, having yoked the steeds in his father's chariot, because he was not able to drive them in the path of his father, burnt up all that was upon the earth, and was himself destroyed by a thunderbolt. Now this has the form of a myth, but really signifies a declination of the bodies moving in the heavens around the earth, and a great conflagration of things upon the earth, which recurs after long intervals."[5]

The history of Atlantis is postponed to Critias. The main content of the dialogue, the exposition by Timaeus, follows.

Synopsis of Timaeus' account[]

Nature of the physical world[]

Timaeus begins with a distinction between the physical world, and the eternal world. The physical one is the world which changes and perishes: therefore it is the object of opinion and unreasoned sensation. The eternal one never changes: therefore it is apprehended by reason (28a).

The speeches about the two worlds are conditioned by the different nature of their objects. Indeed, "a description of what is changeless, fixed and clearly intelligible will be changeless and fixed," (29b), while a description of what changes and is likely, will also change and be just likely. "As being is to becoming, so is truth to belief" (29c). Therefore, in a description of the physical world, one "should not look for anything more than a likely story" (29d).

Timaeus suggests that since nothing "becomes or changes" without cause, then the cause of the universe must be a demiurge or a god, a figure Timaeus refers to as the father and maker of the universe. And since the universe is fair, the demiurge must have looked to the eternal model to make it, and not to the perishable one (29a). Hence, using the eternal and perfect world of "forms" or ideals as a template, he set about creating our world, which formerly only existed in a state of disorder.

Purpose of the universe[]

Timaeus continues with an explanation of the creation of the universe, which he ascribes to the handiwork of a divine craftsman. The demiurge, being good, wanted there to be as much good as was the world. The demiurge is said to bring order out of substance by imitating an unchanging and eternal model (paradigm). The ananke, often translated as 'necessity', was the only other co-existent element or presence in Plato's cosmogony. Later Platonists clarified that the eternal model existed in the mind of the Demiurge.

Properties of the universe[]

Timaeus describes the substance as a lack of homogeneity or balance, in which the four elements (earth, air, fire and water) were shapeless, mixed and in constant motion. Considering that order is favourable over disorder, the essential act of the creator was to bring order and clarity to this substance. Therefore, all the properties of the world are to be explained by the demiurge's choice of what is fair and good; or, the idea of a dichotomy between good and evil.

First of all, the world is a living creature. Since the unintelligent creatures are in their appearance less fair than intelligent creatures, and since intelligence needs to be settled in a soul, the demiurge "put intelligence in soul, and soul in body" in order to make a living and intelligent whole. "Wherefore, using the language of probability, we may say that the world became a living creature truly endowed with soul and intelligence by the providence of God" (30a-b).

Then, since the part is imperfect compared to the whole, the world had to be one and only. Therefore, the demiurge did not create several worlds, but a single unique world (31b). Additionally, because the demiurge wanted his creation to be a perfect imitation of the Eternal "One" (the source of all other emanations), there was no need to create more than one world.

The creator decided also to make the perceptible body of the universe by four elements, in order to render it proportioned. Indeed, in addition to fire and earth, which make bodies visible and solid, a third element was required as a mean: "two things cannot be rightly put together without a third; there must be some bond of union between them". Moreover, since the world is not a surface but a solid, a fourth mean was needed to reach harmony: therefore, the creator placed water and air between fire and earth. "And for these reasons, and out of such elements which are in number four, the body of the world was created, and it was harmonised by proportion" (31-33).

As for the figure, the demiurge created the world in the geometric form of a globe. Indeed, the round figure is the most perfect one, because it comprehends or averages all the other figures and it is the most omnimorphic of all figures: "he [the demiurge] considered that the like is infinitely fairer than the unlike" (33b).

The creator assigned then to the world a rotatory or circular movement, which is the "most appropriate to mind and intelligence" on account of its being the most uniform (34a).

Finally, he created the soul of the world, placed that soul in the center of the world's body and diffused it in every direction. Having thus been created as a perfect, self-sufficient and intelligent being, the world is a god (34b).

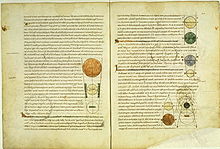

The creation of the world-soul[]

Timaeus then explains how the soul of the world was created (Plato's following discussion is obscure, and almost certainly intended to be read in light of the Sophist). The demiurge combined three elements: two varieties of Sameness (one indivisible and another divisible), two varieties of Difference (again, one indivisible and another divisible), and two types of Being (or Existence, once more, one indivisible and another divisible). From this emerged three compound substances, intermediate (or mixed) Being, intermediate Sameness, and intermediate Difference. From this compound one final substance resulted, the world-soul.[6] He then divided following precise mathematical proportions, cutting the compound lengthways, fixed the resulting two bands in their middle, like in the letter Χ (chi), and connected them at their ends, to have two crossing circles. The demiurge imparted on them a circular movement on their axis: the outer circle was assigned Sameness and turned horizontally to the right, while the inner circle was assigned to Difference and turned diagonally and to the left (34c-36c).

The demiurge gave the primacy to the motion of Sameness and left it undivided; but he divided the motion of Difference in six parts, to have seven unequal circles. He prescribed these circles to move in opposite directions, three of them with equal speeds, the others with unequal speeds, but always in proportion. These circles are the orbits of the heavenly bodies: the three moving at equal speeds are the Sun, Venus and Mercury, while the four moving at unequal speeds are the Moon, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn (36c-d). The complicated pattern of these movements is bound to be repeated again after a period called a 'complete' or 'perfect' year (39d).

Then, the demiurge connected the body and the soul of the universe: he diffused the soul from the center of the body to its extremities in every direction, allowing the invisible soul to envelop the visible body. The soul began to rotate and this was the beginning of its eternal and rational life (36e).

Therefore, having been composed by Sameness, Difference and Existence (their mean), and formed in right proportions, the soul declares the sameness or difference of every object it meets: when it is a sensible object, the inner circle of the Diverse transmit its movement to the soul, where opinions arise, but when it is an intellectual object, the circle of the Same turns perfectly round and true knowledge arises (37a-c).

The elements[]

Timaeus claims that the minute particle of each element had a special geometric shape: tetrahedron (fire), octahedron (air), icosahedron (water), and cube (earth).

|

|

|

|

|

| Tetrahedron (fire) | Octahedron (air) | Icosahedron (water) | Cube (earth) |

Timaeus makes conjectures on the composition of the four elements which some ancient Greeks thought constituted the physical universe: earth, water, air, and fire. Timaeus links each of these elements to a certain Platonic solid: the element of earth would be a cube, of air an octahedron, of water an icosahedron, and of fire a tetrahedron.[7] Each of these perfect polyhedra would be in turn composed of triangular faces the 30-60-90 and the 45-45-90 triangles. The faces of each element could be broken down into its component right-angled triangles, either isosceles or scalene, which could then be put together to form all of physical matter. Particular characteristics of matter, such as water's capacity to extinguish fire, was then related to shape and size of the constituent triangles. The fifth element (i.e. Platonic solid) was the dodecahedron, whose faces are not triangular, and which was taken to represent the shape of the Universe as a whole, possibly because of all the elements it most approximates a sphere, which Timaeus has already noted was the shape into which God had formed the Universe.[8]

The extensive final part of the dialogue addresses the creation of humans, including the soul, anatomy, perception, and transmigration of the soul.

Later influence[]

The Timaeus was translated into Latin first by Marcus Tullius Cicero around 45 BC (sections 27d–47b),[9] and later by Calcidius in the 4th century AD (up to section 53c). Cicero's fragmentary translation was highly influential in late antiquity, especially on Latin-speaking Church Fathers such as Saint Augustine who did not appear to have access to the original Greek dialogue.[10] The manuscript production and preservation of Cicero's Timaeus (among many other Latin philosophical works) is largely due to the works of monastic scholars, especially at Corbie in North-East France during the Carolingian Period.[11]

Calcidius' more extensive translation of the Timaeus had a strong influence on medieval Neoplatonic cosmology and was commented on particularly by 12th century Christian philosophers of the Chartres School, such as Thierry of Chartres and William of Conches, who, interpreting it in the light of the Christian faith, understood the dialogue to refer to a creatio ex nihilo.[12] Calcidius himself never explicitly linked the Platonic creation myth in the Timaeus with the Old Testament creation story in Genesis in his commentary on the dialogue.[13]

The dialogue was also highly influential in Arabic-speaking regions beginning in the 10th century AD The Catalogue (fihrist) of Ibn al-Nadīm provides some evidence for an early translation by Ibn al-Bitriq (Al-Kindī’s circle). It is believed that the Syrian Nestorian Christian (809–873 AD) corrected this translation or translated the entire work himself. However, only the circulation of many exegeses of Timaeus is confirmed.[14] There is also evidence of Galen's commentary on the dialogue being highly influential in the Arabic-speaking world, with Galen's Synopsis being preserved in a medieval Arabic translation.[15]

In his introduction to Plato's Dialogues, 19th-century translator Benjamin Jowett argues that "Of all the writings of Plato, the Timaeus is the most obscure and repulsive to the modern reader."[16]

See also[]

- Sophist

- Statesman

- Philebus

- Proclus

- Marcus Tullius Cicero

- Calcidius

- Augustine

- Johannes Kepler

- Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

- Plotinus

- Esoteric cosmology

- Platonic solids

- Khôra

- Religious cosmology

- Creation myth

- Teleological argument

- Atlantis

Notes[]

- ^ See Burnet, John (1913). Greek Philosophy, Part 1: Thales to Plato. London: Macmillan, p. 328

- ^ Taylor, AE (1928). A commentary on Plato's Timaeus. Oxford: Clarendon, p. 23.

- ^ Nails, Debra (2002). "Critias III," in The People of Plato. Indianapolis: Hackett, pp. 106–7.

- ^ "Philolaus". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- ^ Translation by Benjamin Jowett (1817-1893) reproduced in, for example, John Michael Greer, Atlantis (Llewelyn Worldwide 2007 ISBN 978-0-73870978-9), p. 9

- ^ "The components from which he made the soul and the way in which he made it were as follows: In between the Being that is indivisible and always changeless, and the one that is divisible and comes to be in the corporeal realm, he mixed a third, intermediate form of being, derived from the other two. Similarly, he made a mixture of the Same, and then one of the Different, in between their indivisible and their corporeal, divisible counterparts. And he took the three mixtures and mixed them together to make a uniform mixture, forcing the Different, which was hard to mix, into conformity with the Same. Now when he had mixed these two with Being, and from the three had made a single mixture, he redivided the whole mixture into as many parts as his task required, each part remaining a mixture of the Same, the Different and Being." (35a-b), translation Donald J. Zeyl

- ^ Plato, Timaeus, 53c

- ^ Plato offers an analysis of third kind of reality, between the intelligible and the sensible, namely as Khôra (χώρα). This designates a receptacle (Timaeus 48e), a space, a material substratum, or an interval in which the "forms" were originally held; it "gives space" and has maternal overtones (a womb, matrix). For recent studies on this notion and its impact not only in history of philosophy but on phenomenology see for example: Nader El-Bizri, "‘Qui-êtes vous Khôra?’: Receiving Plato’s Timaeus," Existentia Meletai-Sophias, Vol. XI, Issue 3-4 (2001), pp. 473–490; Nader El-Bizri, "ON KAI KHORA: Situating Heidegger between the Sophist and the Timaeus," Studia Phaenomenologica, Vol. IV, Issue 1-2 (2004), pp. 73–98 [1]; Nader El-Bizri, "Ontopoiēsis and the Interpretation of Plato’s Khôra," Analecta Husserliana: The Yearbook of Phenomenological Research, Vol. LXXXIII (2004), pp. 25–45.

- ^ Cicero's version can be found at http://www.forumromanum.org/literature/cicero_timaeus.html

- ^ Hoenig, Christina (2018). Plato's Timaeus and the Latin Tradition. Cambridge University Press. p. 220.

- ^ Ganz, D. (1990). Corbie in the Carolingian Renaissance. Paris.

- ^ Stiefel, Tina (1985). The Intellectual Revolution in Twelfth Century Europe. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-41892-2.

- ^ Magee, John (2016). On Plato's Timaeus. Calcidius. Harvard University Press. pp. viii–xi.

- ^ "Arabic Translations of Platonic works". Encyclopedia of Plato.

- ^ Das, Aileen R. (September 2013). Galen and the Arabic traditions of Plato's Timaeus (phd). University of Warwick.

- ^ Bauer, Susan Wise (2015). The Story of Science: From the Writings of Aristotle to the Big Bang Theory (1st ed.). New York: W. W. Norton. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-393-24326-0. OCLC 891611100.

References[]

- Broadie, S. (2012). Nature and Divinity in Plato’s Timaeus. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Cornford, Francis Macdonald (1997) [1935]. Plato's Cosmology: The Timaeus of Plato, Translated with a Running Commentary. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-87220-386-0.

- Gregory, A. (2000). Plato’s Philosophy of Science. London: Duckworth.

- Lennox, J. (1985). "Plato’s Unnatural Teleology." In Platonic Investigations. Edited by D. J. O’Meara, 195–218. Studies in Philosophy and the History of Philosophy 13. Washington, DC: Catholic Univ. of America Press.

- Martin, Thomas Henry (1981) [1841]. Études sur le Timée de Platon. Paris: Librairie philosophique J. Vrin.

- Mohr, R. D., and B. M. Sattler, eds. (2010). One Book, the Whole Universe: Plato’s Timaeus Today. Las Vegas, NV: Parmenides.

- Morgan, K. A. (1998). "Designer History: Plato’s Atlantis Story and Fourth-Century Ideology". Journal of Hellenic Studies 118:101–118.

- Morrow, G. R. 1950. "Necessity and Persuasion in Plato’s Timaeus." Philosophical Review 59.2: 147–163.

- Murray, K. Sarah-Jane (2008). From Plato to Lancelot: A Preface to Chretien de Troyes. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-3160-6.

- Osborne, C. (1996). "Space, Time, Shape, and Direction: Creative Discourse in the Timaeus." In Form and Argument in Late Plato. Edited by C. Gill and M. M. McCabe, 179–211. Oxford: Clarendon.

- Pears, Colin David. (2015-2016). "Congruency and Evil in Plato’s Timaeus." The Review of Metaphysics: A Philosophical Quarterly 69.1: 93–113.

- Reydams-Schils, G. J. ed. (2003). Plato’s Timaeus as Cultural Icon. Notre Dame, IN: Univ. of Notre Dame Press.

- Sallis, John (1999). Chorology: On Beginning in Plato's "Timaeus". Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-21308-2.

- Slaveva-Griffin, Svetla. (2005). "'A Feast of Speeches': Form and Content in Plato's Timaeus." Hermes 133.3: 312–327.

- Taylor, Alfred E. (1928). A Commentary on Plato's Timaeus. Oxford: Clarendon.

External links[]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Library resources about Plato's Timaeus |

- Zeyl, Donald. "Plato's Timaeus". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- "Plato: Organicism". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Greek text at Perseus

- Greek text at Greek Wikisource

- Project Gutenberg edition (includes Benjamin Jowett's introduction)

- R. G. Bury translation at Perseus

- York University edition

- Bilingual Edition of Plato's Timaeus in English and Greek side by side

- "Platonic Solids and Plato's Theory of Everything". MathPages.com.

- Digby 23 Project at Baylor University

- Dialogues of Plato

- Books about Atlantis

- Physical cosmology

- Natural philosophy

- Historical physics publications

- Metaphysics literature