The Clouds

| The Clouds | |

|---|---|

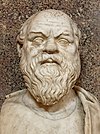

Strepsiades, his son, and Socrates (from a 16th-century engraving) | |

| Written by | Aristophanes |

| Chorus | Clouds (goddesses) |

| Characters |

Silent roles

|

| Setting | 1. House of Strepsiades 2. The Thinkery (Socrates' school) |

The Clouds (Ancient Greek: Νεφέλαι Nephelai) is a Greek comedy play written by the playwright Aristophanes. A lampooning of intellectual fashions in classical Athens, it was originally produced at the City Dionysia in 423 BC and was not as well received as the author had hoped, coming last of the three plays competing at the festival that year. It was revised between 420 and 417 BC and was thereafter circulated in manuscript form.[3]

No copy of the original production survives, and scholarly analysis indicates that the revised version is an incomplete form of Old Comedy. This incompleteness, however, is not obvious in translations and modern performances.[4]

Retrospectively, The Clouds can be considered the world's first extant "comedy of ideas"[5] and is considered by literary critics to be among the finest examples of the genre.[6] The play also, however, remains notorious for its caricature of Socrates and is mentioned in Plato's Apology as a contributor to the philosopher's trial and execution.[7][8]

Characters[]

- Socrates, the philosopher who runs The Thinkery

- Strepsiades, student who joins The Thinkery

- Pheidippides, his son

- Chaerephon, disciple of Socrates

- The Clouds

Plot[]

The play begins with Strepsiades suddenly sitting up in bed while his son, Pheidippides, remains blissfully asleep in the bed next to him. Strepsiades complains to the audience that he is too worried about household debts to get any sleep – his wife (the pampered product of an aristocratic clan) has encouraged their son's expensive interest in betting on horse races. Strepsiades, having thought up a plan to get out of debt, wakes the youth gently and pleads with him to do something for him. Pheidippides at first agrees to do as he's asked then changes his mind when he learns that his father wants to enroll him in The Thinkery, a school for wastrels and bums that no self-respecting, athletic young man dares to be associated with. Strepsiades explains that students of The Thinkery learn how to turn inferior arguments into winning arguments and this is the only way he can beat their aggrieved creditors in court. Pheidippides however will not be persuaded and Strepsiades decides to enroll himself in The Thinkery in spite of his advanced age.

There he meets a student who tells him about some of the recent discoveries made by Socrates, the head of The Thinkery, including a new unit of measurement for ascertaining the distance jumped by a flea (a flea's foot, created from a minuscule imprint in wax), the exact cause of the buzzing noise made by a gnat (its rear end resembles a trumpet) and a new use for a large pair of compasses (as a kind of fishing-hook for stealing cloaks from pegs over the gymnasium wall). Impressed, Strepsiades begs to be introduced to the man behind these discoveries. The wish is soon granted: Socrates appears overhead, wafted in a basket at the end of a rope, the better to observe the Sun and other meteorological phenomena. The philosopher descends and quickly begins the induction ceremony for the new elderly student, the highlight of which is a parade of the Clouds, the patron goddesses of thinkers and other layabouts. The Clouds arrive singing majestically of the regions whence they arose and of the land they have now come to visit, loveliest in all being Greece. Introduced to them as a new devotee, Strepsiades begs them to make him the best orator in Greece by a hundred miles. They reply with the promise of a brilliant future. Socrates leads him into the dingy Thinkery for his first lesson and The Clouds step forward to address the audience.

Putting aside their cloud-like costumes, The Chorus declares that this is the author's cleverest play and that it cost him the greatest effort. It reproaches the audience for the play's failure at the festival, where it was beaten by the works of inferior authors, and it praises the author for originality and for his courage in lampooning influential politicians such as Cleon. The Chorus then resumes its appearance as clouds, promising divine favours if the audience punishes Cleon for corruption and rebuking Athenians for messing about with the calendar, since this has put Athens out of step with the moon.

Socrates returns to the stage in a huff, protesting against the ineptitude of his new elderly student. He summons Strepsiades outside and attempts further lessons, including a form of meditative incubation in which the old man lies under a blanket while thoughts are supposed to arise in his mind naturally. The incubation results in Strepsiades masturbating under the blanket and finally Socrates refuses to have anything more to do with him. The Clouds advise Strepsiades to find someone younger to do the learning for him. His son, Pheidippides, subsequently yields to threats by Strepsiades and reluctantly returns with him to the Thinkery, where they encounter the personified arguments Superior (Right) and Inferior (Wrong), associates of Socrates. Superior Argument and Inferior Argument debate with each other over which of them can offer the best education. Superior Argument sides with Justice and the gods, offering to prepare Pheidippides for an earnest life of discipline, typical of men who respect the old ways; Inferior Argument, denying the existence of Justice, offers to prepare him for a life of ease and pleasure, typical of men who know how to talk their way out of trouble. At the end of the debate, a quick survey of the audience reveals that buggers – people schooled by Inferior Arguments – have got into the most powerful positions in Athens. Superior Argument accepts his inevitable defeat, Inferior Argument leads Pheidippides into the Thinkery for a life-changing education and Strepsiades goes home happy. The Clouds step forward to address the audience a second time, demanding to be awarded first place in the festival competition, in return for which they promise good rains – otherwise they'll destroy crops, smash roofs and spoil weddings.

The story resumes with Strepsiades returning to The Thinkery to fetch his son. A new Pheidippides emerges, startlingly transformed into the pale nerd and intellectual man that he had once feared to become. Rejoicing in the prospect of talking their way out of financial trouble, Strepsiades leads the youth home for celebrations, just moments before the first of their aggrieved creditors arrives with a witness to summon him to court. Strepsiades comes back on stage, confronts the creditor and dismisses him contemptuously. A second creditor arrives and receives the same treatment before Strepsiades returns indoors to continue the celebrations. The Clouds sing ominously of a looming debacle and Strepsiades again comes back on stage, now in distress, complaining of a beating that his new son has just given him in a dispute over the celebrations. Pheidippides emerges coolly and insolently debates with his father a father's right to beat his son and a son's right to beat his father. He ends by threatening to beat his mother also, whereupon Strepsiades flies into a rage against The Thinkery, blaming Socrates for his latest troubles. He leads his slaves, armed with torches and mattocks, in a frenzied attack on the disreputable school. The alarmed students are pursued offstage and the Chorus, with nothing to celebrate, quietly departs.

Historical background[]

The Clouds represents a departure from the main themes of Aristophanes' early plays – Athenian politics, the Peloponnesian War and the need for peace with Sparta. The Spartans had recently stopped their annual invasions of Attica after the Athenians had taken Spartan hostages in the Battle of Sphacteria in 425 and this, coupled with a defeat suffered by the Athenians at the Battle of Delium in 424, had provided the right conditions for a truce. Thus the original production of The Clouds in 423 BC came at a time when Athens was looking forward to a period of peace. Cleon, the populist leader of the pro-war faction in Athens, was a target in all Aristophanes' early plays and his attempts to prosecute Aristophanes for slander in 426 had merely added fuel to the fire. Aristophanes however had singled Cleon out for special treatment in his previous play The Knights in 424 and there are relatively few references to him in The Clouds.

Freed from political and war-time issues, Aristophanes focuses in The Clouds on a broader issue that underlies many conflicts depicted in his plays – the issue of Old versus New, or the battle of ideas.[9] The scientific speculations of Ionian thinkers such as Thales in the sixth century were becoming commonplace knowledge in Aristophanes' time and this had led, for instance, to a growing belief that civilized society was not a gift from the gods but rather had developed gradually from primitive man's animal-like existence.[10] Around the time that The Clouds was produced, Democritus at Abdera was developing an atomistic theory of the cosmos and Hippocrates at Cos was establishing an empirical and science-like approach to medicine. Anaxagoras, whose works were studied by Socrates, was living in Athens when Aristophanes was a youth. Anaxagoras enjoyed the patronage of influential figures such as Pericles, but oligarchic elements also had political advocates and Anaxagoras was charged with impiety and expelled from Athens around 437 BC.

The battle of ideas had led to some unlikely friendships that cut across personal and class differences, such as between the socially alert Pericles and the unworldly Anaxagoras, and between the handsome aristocrat, Alcibiades, and the ugly plebeian, Socrates. Socrates moreover had distinguished himself from the crowd by his heroism in the retreat from the Battle of Delium and this might have further singled him out for ridicule among his comrades.[11] He was forty-five years old and in good physical shape when The Clouds was produced[12] yet he had a face that lent itself easily to caricature by mask-makers, possibly a contributing reason for the frequent characterization of him by comic poets.[13] In fact one of the plays that defeated The Clouds in 423 was called Connus, written by Ameipsias, and it too lampooned Socrates.[14] There is a famous story, as reported for example by Aelian, according to which Socrates cheerfully rose from his seat during the performance of The Clouds and stood in silent answer to the whispers among foreigners in the festival audience: "Who is Socrates?"[15]

Portrayal of Socrates[]

Plato appears to have considered The Clouds a contributing factor in Socrates' trial and execution in 399 BC. There is some support for his opinion even in the modern age.[16] Aristophanes' plays however were generally unsuccessful in shaping public attitudes on important questions, as evidenced by their ineffectual opposition to the Peloponnesian War, demonstrated in the play Lysistrata, and to populists such as Cleon. Moreover, the trial of Socrates followed Athens' traumatic defeat by Sparta, many years after the performance of the play, when suspicions about the philosopher were fuelled by public animosity towards his disgraced associates such as Alcibiades.[17]

Socrates is presented in The Clouds as a petty thief, a fraud and a sophist with a specious interest in physical speculations. However, it is still possible to recognize in him the distinctive individual defined in Plato's dialogues.[18] The practice of asceticism (as for example idealized by the Chorus in lines 412–19), disciplined, introverted thinking (as described by the Chorus in lines 700–6) and conversational dialectic (as described by Socrates in lines 489–90) appear to be caricatures of Socratic behaviours later described more sympathetically by Plato. The Aristophanic Socrates is much more interested in physical speculations than is Plato's Socrates, yet it is possible that the real Socrates did take a strong interest in such speculations during his development as a philosopher[19] and there is some support for this in Plato's dialogues Phaedo 96A and Timaeus.

It has been argued that Aristophanes caricatured a 'pre-Socratic' Socrates and that the philosopher depicted by Plato was a more mature thinker who had been influenced by such criticism.[18] Conversely, it is possible that Aristophanes' caricature of the philosopher merely reflects his own ignorance of philosophy.[20] According to yet another view, The Clouds can best be understood in relation to Plato's works, as evidence of a historic rivalry between poetic and philosophical modes of thought.[21]

The Clouds and Old Comedy[]

During the parabasis proper (lines 518–62), the Chorus reveals that the original play was badly received when it was produced. References in the same parabasis to a play by Eupolis called Maricas produced in 421 BC and criticism of the populist politician Hyperbolus who was ostracized in 416 indicate that the second version of The Clouds was probably composed somewhere between 421–16 BC. The parabasis also includes an appeal to the audience to prosecute Cleon for corruption. Since Cleon died in 422 it can be assumed that this appeal was retained from the original production in 423 and thus the extant play must be a partial revision of the original play.[22]

The revised play is an incomplete form of Old Comedy. Old Comedy conventionally limits the number of actors to three or four, yet there are already three actors on stage when Superior and Inferior enter the action and there is no song at that point that would allow for a change of costume. The play is unusually serious for an Old Comedy and possibly this was the reason why the original play failed at the City Dionysia.[16] As a result of this seriousness, there is no celebratory song in the exodus, and this also is an uncharacteristic omission. A typical Aristophanic Chorus, even if it starts out as hostile to the protagonist, is the protagonist's cheer squad by the end of the play. In The Clouds however, the Chorus appears sympathetic at first but emerges as a virtual antagonist by the end of the play.

The play adapts the following elements of Old Comedy in a variety of novel ways.

- Parodos: The arrival of the Chorus in this play is unusual in that the singing begins offstage some time before the Chorus appears. It is possible that the concealed Chorus was not fully audible to the audience and this might have been a factor in the original play's failure.[23] Moreover, the majestic opening song is more typical of tragedy than comedy.[24]

- Parabasis: The parabasis proper (lines 518–62) is composed in eupolidean tetrameter rather than the conventional anapestic tetrameter. Aristophanes does not use eupolideans in any other of his extant plays.[25] The first parabasis (510–626) is otherwise conventional. However the second parabasis (1113–30) is in a shortened form, comprising an epirrhema in trochaic tetrameter but without the songs and the antepirrhema needed for a conventional, symmetrical scene.

- Agon: The play has two agons. The first is between Superior and Inferior (949–1104). Superior's arguments are in conventional anapestic tetrameter but Inferior presents his case in iambic tetrameters, a variation that Aristophanes reserves for arguments that are not to be taken seriously.[26] A similar distinction between anapestic and iambic arguments is made in the agons in The Knights[27] and The Frogs.[28] The second agon in The Clouds is between Strepsiades and his son (1345–1451) and it is in iambic tetrameter for both speakers.

- Episodes: Informal dialogue between characters is conventionally in iambic trimeter. However the scene introducing Superior and Inferior is conducted in short lines of anapestic rhythm (889–948). Later, in the agon between Strepsiades and his son, a line of dialogue in iambic trimeter (1415) – adapted from Euripides' Alcestis – is inserted into a speech in iambic tetrameter, a transition that seems uncharacteristically clumsy.[29]

English translations[]

- Benjamin Dann Walsh, The Comedies of Aristophanes, vol. 1, 1837. 3 vols. English metre.

- , 1853 – prose: full text

- Benjamin B. Rogers, 1924 – verse: full text

- Arthur S. Way, 1934 – verse

- F. L. Lucas, 1954 – verse

- , 1960 – verse

- William Arrowsmith, 1962 – prose and verse

- Alan H. Sommerstein, 1973 – prose and verse: available for digital loan

- Thomas G. West and Grace Starry West, 1984 – prose

- Peter Meineck, 1998 – prose

- (prose), John Curtis Franklin (metrical translation of choral lyrics), 2000 [1][2]

- Edward Tomlinson, Simon R. B. Andrews and Alexandra Outhwaite, 2007 – prose and verse (for Kaloi k'Agathoi)

- George Theodoridis, 2007 – prose: full text

- Ian C. Johnston, 2008 – verse: full text

- Michael A. Tueller, 2011 – prose

- Moses Hadas: available for digital loan

- The Atticist, 2021 – prose and verse with commentary: full text

Earlier translations into other languages exist, including:

- Italian: Bartolomio & Pietro Rositini de Prat'Alboino. 'Le Nebule', in Le Commedie del Facetissimo Aristofane. Venice ("Vinegia"), 1545.[30]

- German: Isaac Fröreisen. Nubes. Ein Schön und Kunstreich Spiel, darin klärlich zusehen, was betrug und hinderlist offtmahlen für ein End nimmet. Strasbourg ("Straßburg"), 1613.

- Latin: Stephanus Berglerus and Carl Andreas Duker. "Nubes". In Aristophanis comoediis undecim, Graece et Latine. nl|Samuelem et Ioannem Luchtmans, predecessor of Brill Publishers. Leiden ("Lugduni Batavorum"), 1760.

Adaptations[]

- Andrew David Irvine, 2007 – prose, Socrates on Trial: A Play Based on Aristophane's Clouds and Plato's Apology, Crito, and Phaedo Adapted for Modern Performance

Performances[]

- The Oxford University Dramatic Society staged it in the original Greek in 1905, with C.W.Mercer as Strepsiades and Compton Mackenzie as Pheidippides.[31]

- Nottingham New Theatre staged an adaptation of the play from 17–20 March 2009. It was directed by Michael Moore; with Alexander MacGillivray as Strepsiades, Lucy Preston as Pheidippides and Topher Collins as Socrates.

Citations[]

- ^ Aristophanes:Lysistrata, The Acharnians, The Clouds Alan Sommerstein, Penguin Classics 1973, page 37

- ^ ibidem

- ^ Clouds (1970), page XXIX

- ^ Aristophanes: Lysistrata, The Acharnians, The Clouds A. Somerstein, Penguin Classics 1973, page 107

- ^ Rhetoric, Comedy and the Violence of Language in Aristophanes' Clouds Daphne O'Regan, Oxford University Press US 1992, page 6

- ^ Aristophanes:Old-and-new Comedy – Six essays in perspective Kenneth.J.Reckford, UNC Press 1987, page 393

- ^ The Apology translated by Benjamin Jowett, section4

- ^ Apology, Greek text, edited J Burnet, section 19c

- ^ Aristophanes:Lysistrata, The Acharnians, The Clouds A. Sommerstein, Penguin Classics 1973, pages 16–17

- ^ Early Greek Philosophy Martin West, in 'Oxford History of the Classical World', J.Boardman, J.Griffin and O.Murray (eds), Oxford University Press 1986, page 121

- ^ Aristophanes:Lysistrata, The Acharnians, The Clouds A. Sommerstein, Penguin Classics 1973, pages 108

- ^ Clouds (1970), page XVIII

- ^ Aristophanes: Lysistrata, The Acharnians, Clouds A. Sommerstein, Penguin Classics 1975, page 31

- ^ Aristophanes: Lysistrata, The Acharnians, Clouds A. Sommerstein, Penguin Classics 1975, page 16

- ^ Clouds (1970), page XIX

- ^ Jump up to: a b Aristophanes:Lysistrata, The Acharnians, The Clouds A.Sommerstein, Penguin Classics 1973, page 109

- ^ Clouds (1970), pages XIV–XV

- ^ Jump up to: a b Postmodern Platos Catherine H. Zuckert, University of Chicago Press 1996, page 135

- ^ The Socratic Movement Paul Vander Waerdt, Cornell University Press 1994, page 74

- ^ Clouds (1970), pages XXII

- ^ Postmodern Platos Catherine H.Zuckert, University of Chicago Press 1996, page 133, commenting on Socrates and Aristophanes by Leo Strauss, University of Chicago Press 1994

- ^ Clouds (1970), pages XXVIII–XXIX

- ^ Clouds (1970), page 99 note 275–90

- ^ Clouds (1970), page XXVIII

- ^ Clouds (1970), page 119 note 518–62

- ^ Aristophanes:Wasps D.MacDowell (ed.), Oxford University Press 1971, page 207 note 546–630

- ^ Knights 756–940

- ^ Frogs 895–1098

- ^ Aristophanes:Wasps D.MacDowell (ed.), Oxford University Press 1971, page 187 note 1415

- ^ studio bibliografico pera s.a.s. (Lucca, Italy). "Aristofane. Le Commedie del Facetissimo Aristofane". . Retrieved 2020-12-07.

- ^ Times review March 2nd 1905

References[]

- Dover, K. J. (1970). Aristophanes: Clouds. Oxford University Press.

Further reading[]

- Aristophanes. Hickie, William James (ed.). Clouds – via Perseus Digital Library.

- Brulé, Pierre (September 2007). "Les Nuées et le problème de l'incroyance au Ve siècle". La norme en matière religieuse en Grèce ancienne. Actes du XIIe colloque international du CIERGA. Kernos Suppléments (№ 21) (in French). Rennes. pp. 49–67.

- Irvine, Andrew David (2008). Socrates on Trial: A Play Based on Aristophane's Clouds and Plato's Apology, Crito, and Phaedo Adapted for Modern Performance. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-9783-5.

External links[]

Works related to The Clouds at Wikisource

Works related to The Clouds at Wikisource- The Clouds translated by William James Hickie' at Project Gutenberg

- The Clouds translated by Ian Johnston

- The Clouds: A Study Guide

- John Curtis Franklin – Aristophanes Clouds Essay

- On Satire in Aristophanes's The Clouds has a very good analysis of The Clouds and on satire in general.(Includes full version of the text with commentaries)

The Clouds public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Clouds public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- Plays by Aristophanes

- Plays set in the 5th century BC

- Cultural depictions of Socrates

- Parodies

- Plays set in ancient Greece

- Athens in fiction