South Asian river dolphin

| South Asian river dolphin | |

|---|---|

| |

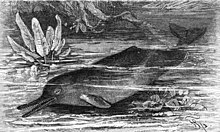

| P. gangetica leaping out of the water | |

| |

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Platanistidae |

| Genus: | Platanista Wagler, 1830 |

| Species | |

|

Platanista gangetica | |

| |

| Ranges of the Ganges river dolphin and of the Indus river dolphin | |

The South Asian river dolphins are two species of toothed whales in the genus Platanista, both of which are found in freshwater habitats in northern South Asia.[2] Both species in the genus are endangered.

Until 1998, they were regarded as two separate species; in 1998, the classification was changed from two separate species to subspecies. More recent studies have recovered them as distinct species, and they have thus been reclassified as such.[3]

Taxonomy and evolution[]

Until the 1970s, the South Asian river dolphin was regarded as a single species. The two subspecies are geographically separate and have not interbred for many hundreds if not thousands of years. Based on differences in skull structure, vertebrae, and lipid composition scientists declared the two populations as separate species in the early 1970s.[4]

In 1998, the results of these studies were questioned and the classification reverted to the pre-1970 consensus of a single species containing two subspecies until the taxonomy could be resolved using modern techniques such as molecular sequencing. The latest analyses of mitochondrial DNA of the two populations did not display the variances needed to support their classification as separate species.[5][6] However, a 2021 study re-analyzed the two populations and found significant genetic divergence and major differences in the structure of their skulls; this, when combined with the fact that the Ganges and Indus basins had not been contiguous for over 40 million years (indicating that the event that split the two species was likely a chance event with no gene flow between the split populations afterwards) led to the conclusion that both were indeed distinct species.[3]

- Synonyms

- blind river dolphin, side-swimming dolphin

An assessment of divergence rates in mitochondrial DNA of the two species indicates that they diverged from a common ancestor around 550,000 years ago, likely in a case of stream capture that briefly connected the Indus and Ganges basins, allowing dolphins to travel through both, up until the rivers reverted to their previous state and isolated the dolphins in new habitats.[3] The ancestor of the genus Platanista is thought to have been a marine platanistid inhabiting the epi-continental seas in South Asia during the sea level rises in the middle Miocene.[5] The earliest fossil identified as belonging to the genus only 12,000 years old.[1]

Description[]

The South Asian river dolphins have the long, pointed nose characteristic of all river dolphins. Their teeth are visible in both the upper and lower jaws even when the mouth is closed. The teeth of young animals are almost an inch long, thin and curved; as animals age, the teeth undergo considerable changes and in mature adults become square, bony, flat disks. The snout thickens towards its end. Navigation and hunting are carried out using echolocation.[7] They are unique among cetaceans in that they swim on their sides.[8] The body is a brownish color and stocky at the middle. The species has only a small, triangular lump in the place of a dorsal fin. The flippers and tail are thin and large in relation to the body size, which is about 2-2.2 meters in males and 2.4–2.6 m in females. Mature females are larger than males. Sexual dimorphism is expressed after females reach about 150 cm (59 in); the female rostrum continues to grow after the male rostrum stops growing, eventually reaching approximately 20 cm (7.9 in) longer.

Biology[]

Life cycle[]

Births may take place year round, but appear to be concentrated between December to January and March to May.[9] Females gestate on average once every two years; gestation is thought to be approximately 9–10 months. After around one year, juveniles are weaned and they reach sexual maturity at about 10 years of age.[10] During the monsoon, South Asian river dolphins tend to migrate to tributaries of the main river systems.[9] Occasionally, individuals swim along with their beaks emerging from the water,[11] and they may "breach"; jumping partly or completely clear of the water and landing on their sides.[11]

Diet[]

South Asian river dolphins rely on echolocation to find prey due to their poor eyesight. Their extended rostrum is advantageous in detecting hidden or hard-to-find prey items. The prey is held in their jaws and swallowed. Their teeth are used as a clamp rather than a chewing mechanism.[12]

The genus feeds on a variety of shrimp and fish, including carp and catfish. They are usually encountered on their own or in loose aggregations; the dolphins do not form tight interacting groups.[13][12]

Vision[]

The genus lacks a crystalline eye lens and has evolved a flat cornea. The combination of these traits makes the eye incapable of forming clear images on the retina and renders the dolphin effectively blind, but the eye may still serve as a light receptor. The retina contains a densely packed receptor layer, a very thin bipolar and ganglion cell layer, and a tiny optic nerve (with only a few hundred optic fibers) that are sufficient for the retina to act as a light-gathering component.[14] Although its eye lacks a lens (this species is also referred to as the "blind dolphin"), the dolphin still uses its eye to locate itself. The species has a slit similar to a blowhole on the top of the head, which acts as a nostril.[15]

The dense pigmentation in the skin overlying the eye prevents light from reaching the retina from any entrance except for a pinhole sphincter-like structure. This structure is controlled by a cone-shaped muscle layer that extends from the posterior eye orbit to the overlying eye skin layer. The sphincter-like structure is capable of sensing light and may be able to sense the direction from where the light was emitted. The muddy waters and low light conditions that Platanista inhabits negate the use of the little vision that remains.[14]

Distribution and habitat[]

The South Asian river dolphin is native to freshwater river systems in Nepal, India, Bangladesh and Pakistan.[2] They are found the Indus River and connected channels, in the Beas River, in the Ganges and Brahmaputra rivers and their tributaries in Pakistan, India, Bangladesh and Nepal. They live in water with high abundance of prey and reduced flow.[7] It migrates seasonally downstream in colder conditions with lower water levels and upstream in warmer conditions with higher water levels.[16]

Conservation[]

Two assessments in 2014 and 2015 estimated less than 5,000 individuals for the genus as a whole, of which about 3,500 belong to the Ganges river dolphin and about 1,500 to the Indus river dolphin.[17][18]

International trade is prohibited by the listing of the South Asian river dolphins on Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species.[2] It is protected under the Indian Wildlife Act, although these legislations require stricter enforcement.[9] It is listed as Endangered on the Red List of Threatened Species.[2] The Indus river dolphin is listed as endangered by the US government National Marine Fisheries Service under the Endangered Species Act.

The genus is listed on Appendix I[19] and Appendix II[19] of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals.

See also[]

References[]

This article incorporates text from the ARKive fact-file ""Ganges river dolphin"" under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License and the GFDL.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Platanista Wagler 1830 (toothed whale)". Fossilworks.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Braulik, G.T. & Smith, B.D. (2019). "Platanista gangetica (amended version of 2017 assessment)". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T41758A151913336.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Braulik, G. T.; Archer, F. I.; Khan, U.; Imran, M.; Sinha, R. K.; Jefferson, T. A.; Donovan, C.; Graves, J. A. (2021). "Taxonomic revision of the South Asian River dolphins (Platanista): Indus and Ganges River dolphins are separate species". Marine Mammal Science. 37 (3): 1022–1059. doi:10.1111/mms.12801.

- ^ Pilleri, G.; Marcuzzi, G. & Pilleri, O. (1982). "Speciation in the Platanistoidea, systematic, zoogeographical and ecological observations on recent species". Investigations on Cetacea. 14: 15–46.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Braulik, G. T.; Barnett, R.; Odon, V.; Islas-Villanueva, V.; Hoelzel, A. R.; Graves, J. A. (2014). "One Species or Two? Vicariance, lineage divergence and low mtDNA diversity in geographically isolated populations of South Asian River Dolphin". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 22 (1): 111–120. doi:10.1007/s10914-014-9265-6. S2CID 14113756.

- ^ Rice, D.W. (1998). Marine mammals of the world: Systematics and distribution. Society for Marine Mammalogy. ISBN 978-1-891276-03-3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "South Asian river dolphin (Platanista gangetica)". EDGE. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- ^ Herald, E. S.; Brownell Jr, R. L.; Frye, F. L.; Morris, E. J.; Evans, W. E.; Scott, A. B. (12 December 1969). "Blind River Dolphin: First Side-Swimming Cetacean". Science. New Series. 166 (3911): 1408–1410. Bibcode:1969Sci...166.1408H. doi:10.1126/science.166.3911.1408. PMID 5350341. S2CID 5670792.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Boris Culik. "Platanista gangetica (Roxburgh, 1801)". CMS Report. Archived from the original on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- ^ Swinton, J.; W. Gomez & P. Myer. "Platanista gangetica". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society". Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Ganges River Dolphin (Platanista gangetica gangetica)". Dolphins-World. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- ^ "Indus River Dolphin (Platanista gangetica minor)". Dolphins-World. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Herald, Earl S.; Brownell, Robert L.; Frye, Fredric L.; Morris, Elkan J.; Evans, William E.; Scott, Alan B. (1969). "Blind River Dolphin: First Side-Swimming Cetacean". Science. 166 (3911): 1408–1410. Bibcode:1969Sci...166.1408H. doi:10.1126/science.166.3911.1408. JSTOR 1727285. PMID 5350341. S2CID 5670792.

- ^ "Ganges River dolphin". WWF. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ Sinha, R. K.; Kannan, K. (2014). "Ganges River Dolphin: An Overview of Biology, Ecology, and Conservation Status in India". Ambio. 43 (8): 1029–1046. doi:10.1007/s13280-014-0534-7. PMC 4235892. PMID 24924188.

- ^ Sinha, Ravindra K.; Kannan, Kurunthachalam (1 December 2014). "Ganges River Dolphin: An Overview of Biology, Ecology, and Conservation Status in India". AMBIO. 43 (8): 1029–1046. doi:10.1007/s13280-014-0534-7. ISSN 1654-7209. PMC 4235892. PMID 24924188.

- ^ "Review of status, threats, and conservation management options for the endangered Indus River blind dolphin". Biological Conservation. 192: 30–41. 1 December 2015. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2015.09.008. ISSN 0006-3207.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Appendix I and Appendix II Archived 11 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine" of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals as amended by the Conference of the Parties in 1985, 1988, 1991, 1994, 1997, 1999, 2002, 2005, and 2008, effective: 5 March 2009.

Further reading[]

- Randall R. Reeves; Brent S. Stewart; Phillip J. Clapham; James A. Powell (2002). National Audubon Society Guide to Marine Mammals of the World. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. ISBN 0375411410.

- Blind dolphins need space to breath – The Nation (Pakistan)

External links[]

| Wikispecies has information related to Platanista gangetica. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Platanista gangetica. |

- Mueenuddin, N. (2020). Indus River Dolphins From the Sky (Motion picture). Nyal Mueenuddin Wildlife Films.

- Goddess Ganga and the Gangetic Dolphin at Biodiversity of India'

- Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society, South Asian river dolphin: Platanista gangetica

- US National Marine Fisheries Service Indus River Dolphin web page

- ganges river dolphin media from ARKive

- Convention on Migratory Species page on the Ganges River Dolphin

- Walker's Mammals of the World Online – Ganges River Dolphin

- World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) – species profile for the Ganges River dolphin

- River dolphins

- Cetacean genera

- Mammals of South Asia

- Taxa named by Johann Georg Wagler