Soviet famine of 1932–1933

| Part of Famines in the Soviet Union | |

A starving man lying on the ground in Ukraine | |

| Native name | Советский голод 1932-1933 годов (Russian), Радянський голод 1933-1932 років (Ukrainian), 1933 - 1932 жылдардағы кеңестік аштық (Kazakh) |

|---|---|

| Location | Russian SSR, Ukrainian SSR, Kazakh SSR |

| Type | Famine |

| Cause | Disputed; some say low harvest due to demand spiking in Industrialisation in the Soviet Union |

| Motive | Disputed, some say intentionally set up by Stalin due to racial discrimination |

| Target | Ukrainian people and Kazakh people (disputed if intentionally targeted) |

| First reporter | Gareth Jones |

| Filmed by | Alexander Wienerberger |

| Deaths | ~6.4 million – ~12.5 million |

| Suspects | Joseph Stalin |

| Publication bans | Proof of the famine was suppressed by Goskomstat |

| Awards | Pulitzer Prize for Correspondence to Walter Duranty |

The Soviet famine of 1932–1933 killed millions of people in the major grain-producing areas of the Soviet Union, including Ukraine, Northern Caucasus, Volga Region and Kazakhstan,[2] the South Urals, and West Siberia.[3][4] It has been estimated that between 3.3[5] and 3.9 million died in Ukraine,[6] between 2 and 3 million died in Russia,[7] and 1.5–2 million (1.3 million of whom were ethnic Kazakhs) died in Kazakhstan.[8][9][10][11] Gareth Jones was the first Western journalist to report the devastation.[12][13][a]

The exact number of deaths is hard to determine due to a lack of records,[6][14] but the number increases significantly when the deaths in the heavily Ukrainian-populated Kuban region are included.[15] Older estimates are still often cited in political commentary.[16] In 1987, Robert Conquest had cited a number of Kazakhstan losses of one million; a large number of nomadic Kazakhs had roamed abroad, mostly to China and Mongolia. In 2007, David R. Marples estimated that 7.5 million people died as a result of the famine in Soviet Ukraine, of which 4 million were ethnic Ukrainians.[17] According to the findings of the Court of Appeal of Kyiv in 2010, the demographic losses due to the famine amounted to 10 million, with 3.9 million direct famine deaths, and a further 6.1 million birth deficit.[6] Later in 2010, Timothy Snyder estimated that around 3.3 million people died in total in Ukraine.[18] In 2013, it was said that total excess deaths in Ukraine could not have exceeded 2.9 million.[19]

Stalin and other party members had ordered that kulaks were "to be liquidated as a class",[20] and became a target for the state. The richer, land-owning peasants were labeled "kulaks" and were portrayed by the Bolsheviks as class enemies, which culminated in a Soviet campaign of political repressions, including arrests, deportations, and executions of large numbers of the better-off peasants and their families in 1929–1932.[21] Major contributing factors to the famine include the forced collectivization of agriculture as a part of the Soviet first five-year plan, forced grain procurement, combined with rapid industrialisation, a decreasing agricultural workforce, and several bad droughts. Some scholars have classified the famine in Ukraine and famine in Kazakhstan as genocide committed by Joseph Stalin's government,[22][23] targeting ethnic Ukrainians and Kazakhs, while others dispute the relevance of any ethnic motivation, as is frequently implied by that term, and focus instead on the class dynamics between land-owning peasants (kulaks) with strong political interest in private property, and the ruling Soviet Communist Party's fundamental tenets which were diametrically opposed to those interests.[24] In addition to the Kazakh famine of 1919–1922, these events saw Kazakhstan lose more than half of its population within 15 years. The famine made Kazakhs a minority in their own republic. Before the famine, around 60% of the republic's population were Kazakhs; after the famine, only around 38% of the population were Kazakhs.[25][26]

Causes[]

| Mass repression in the Soviet Union |

|---|

| Economic repression |

| Political repression |

| Ideological repression |

| Ethnic repression |

|

Unlike the Russian famine of 1921–1922, Russia's intermittent drought was not severe in the affected areas at this time.[27]

Historian Mark B. Tauger of West Virginia University suggests that the famine was caused by a combination of factors, specifically low harvest due to natural disasters combined with increased demand for food caused by the industrialization and urbanization, and grain exports by the Soviet Union at the same time.[28] The industrialization became a starting mechanism of the famine. Stalin's First Five-Year Plan, adopted by the party in 1928, called for rapid industrialization of the economy. With the greatest share of investment put into heavy industry, widespread shortages of consumer goods occurred while the urban labor force was also increasing. Collectivization employed at the same time was expected to improve agricultural productivity and produce grain reserves sufficiently large to feed the growing urban labor force. The anticipated surplus was to pay for industrialization. Kulaks who were the wealthier peasants encountered particular hostility from the Stalin regime. About one million kulak households (1,803,392 people according to Soviet archival data [29]) were liquidated by the Soviet Union. The kulaks had their property confiscated and were executed, imprisoned in Gulags, or deported to penal labor colonies in neighboring lands in a process called Dekulakization. Forced collectivization of the remaining peasants was often fiercely resisted resulting in a disastrous disruption of agricultural productivity. Forced collectivization helped achieve Stalin's goal of rapid industrialization but it also contributed to a catastrophic famine in 1932–33.[30]

A similar view was presented by Stephen Wheatcroft, who has given more weight to the "ill-conceived policies" of Soviet government and highlighted that while the policy was not targeted at Ukraine specifically, it was Ukraine who suffered most for "demographic reasons".[31] According to Wheatcroft the grain yield for the Soviet Union preceding the famine was a low harvest of between 55 and 60 million tons,[32]: xix–xxi yet official statistics mistakenly reported a yield of 68.9 million tons.[33]

Lewis H. Siegelbaum, Professor of History at Michigan State University, states that Ukraine was hit particularly hard by grain quotas which were set at levels which most farms could not produce. The 1933 harvest was poor, coupled with the extremely high quota level, which led to starvation conditions. The shortages were blamed on kulak sabotage, and authorities distributed what supplies were available only in the urban areas. The loss of life in the Ukrainian countryside is estimated at approximately 5 million people.[34]

Law of Spikelets[]

The "Decree About the Protection of Socialist Property", nicknamed by the farmers the Law of Spikelets, was enacted on August 7, 1932. The purpose of the law was to protect the property of the kolkhoz collective farms. It was nicknamed the Law of Spikelets because it allowed people to be prosecuted for gleaning leftover grain from the fields. There were more than 200,000 people sentenced under this law.[35]

Passports[]

There was a wave of migration due to starvation and authorities responded by introducing a requirement that passports be used to go between republics and banning travel by rail.[citation needed]

Soviet internal passports (identity cards) were introduced on 27 December 1932 to deal with the exodus of peasants from the countryside. Individuals not having such a document could not leave their homes on pain of administrative penalties, such as internment in Gulag labor camps. The rural population had no right to freely keep passports and thus could not leave their villages without approval. The power to issue passports rested with the head of the kolkhoz, and identity documents were kept by the administration of the collective farms. This measure stayed in place until 1974.[citation needed]

The lack of passports could not completely stop peasants' leaving the countryside, but only a small percentage of those who illegally infiltrated into cities could improve their lot. Unable to find work or possibly buy or beg a little bread, farmers died in the streets of Kharkiv, Kyiv, Dnipropetrovsk, Poltava, Vinnytsia, and other major cities of Ukraine.[citation needed]

Reactions[]

The famine of 1932–1933 was officially denied, so any discourse on this issue was classified as criminal "anti-Soviet propaganda" until Perestroika. The results of the 1937 census were kept secret as they revealed the demographic losses attributable to the Great Famine.

Some well-known journalists, most notably Walter Duranty of The New York Times, downplayed the famine and its death toll.[36] In 1932, he received the Pulitzer Prize for Correspondence for his coverage of the Soviet Union's first five-year plan and thus, he was considered the most expert Western journalist to cover the famine.[36] In the article "Russians Hungry, But Not Starving", he responded to an account of starvation in Ukraine and, while acknowledging that there was widespread malnutrition in certain areas of the USSR (including parts of the North Caucasus and Lower Volga), generally disagreed with the scale of the starvation and claimed that there was no famine.[37] Duranty's coverage led directly to Franklin Roosevelt officially recognizing the Soviet Union in 1933 and thus revoked the United States' official recognition of an independent Ukraine.[38] A similar position was taken by the French Prime Minister Edouard Herriot, who toured the territory of Ukraine during his stay in the Soviet Union. Other Western journalists reported on the famine at the time, including Malcolm Muggeridge and Gareth Jones, who both severely criticised Duranty's account and were later banned from returning to the Soviet Union.[39]

As a child, Mikhail Gorbachev experienced the Soviet famine in Stavropol Krai, Russia. He recalled in a memoir that "In that terrible year [in 1933] nearly half the population of my native village, Privolnoye, starved to death, including two sisters and one brother of my father."[40] It has been claimed[by whom?] that George Orwell's Animal Farm was inspired by Gareth Jones's articles about the Great Famine of 1932–1933[41] but this is disputed.[42]

Members of the international community have denounced the USSR government for the events of the years 1932–1933. However, the classification of the Ukrainian famine as a genocide is a subject of debate. A comprehensive criticism is presented by Michael Ellman in the article "Stalin and the Soviet Famine of 1932–33 Revisited" published in the journal Europe-Asia Studies.[43] The author refers to the UN Convention which specifies that genocide is the destruction 'in whole or in part' of a national group, "any acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group".[44] The reasons for the famine are claimed to have been rooted in the industrialization and widespread collectivization of farms that involved escalating taxes, grain-delivery quotas, and dispossession of all property. The latter was met with resistance that was answered by “imposition of ever higher delivery quotas and confiscation of foodstuffs.”[45] As people were left with insufficient amount of food after the procurement, the famine occurred. Therefore, the famine occurred largely due to the policies that favored the goals of collectivization and industrialization rather than the deliberate attempt to destroy the Kazakhs or Ukrainians as a people.[43]

In Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine, Pulitzer Prize winner Anne Applebaum says that the UN definition of genocide is overly narrow, due to the USSR's influence on the Genocide Convention. Instead of a broad definition that would have included the Soviet crimes against kulaks and Ukrainians, Applebaum writes that genocide "came to mean the physical elimination of an entire ethnic group, in a manner similar to the Holocaust. The Holodomor does not meet that criterion ... This is hardly surprising, given that the Soviet Union itself helped shape the language precisely in order to prevent Soviet crimes, including the Holodomor, from being classified as 'genocide.'" Applebaum further states: "The accumulation of evidence means that it matters less, nowadays, whether the 1932–3 famine is called a genocide, a crime against humanity, or simply an act of mass terror. Whatever the definition, it was a horrific assault, carried out by a government against its own people ... That the famine happened, that it was deliberate, and that it was part of a political plan to undermine Ukrainian identity is becoming more widely accepted, in Ukraine as well as in the West, whether or not an international court confirms it."[46]

In her in-depth study Remember the Peasantry: A Study of Genocide, Famine, and the Stalinist Holodomor in Soviet Ukraine, 1932–33, Lesa Melnyczuk Morgan states that the "Holodomor was clearly an act of genocide against the Ukrainian people by Stalin's Soviet regime."[47] Several scholars have disputed that the famine was a genocidal act by the Soviet government, including J. Arch Getty,[48] Stephen G. Wheatcroft,[49] R. W. Davies,[50] and Mark Tauger.[51]

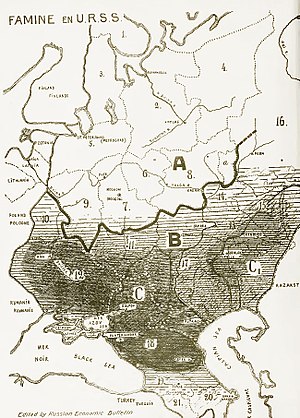

Errors and possible falsifications[]

There are publications whose accuracy is disputed. One example is the Ukraine mortality map published in USA in 1988.[52] The map shows the southwestern districts of the Odessa region as part of the Ukrainian SSR, while in reality they were part of Romania in the 1930s. At the same time, the map fails to show the Moldavian ASSR, which was part of the Ukrainian SSR at that time.[citation needed]

A big notoriety was gained by a story that took place in 2006 under President Viktor Yushchenko. In the Sevastopol Holodomor Museum, there were exhibited photographs, which allegedly showed the victims of the famine in Ukraine, but later it turned out that the pictures were taken during the famine in the Russian Volga region in the early 1920s and in the United States during the Great Depression. These photos also appeared on the website of the President of Ukraine. After the outbreak of the scandal, the exhibition was closed, and the press structure of the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU), from whose archives the pictures were allegedly removed, recognized the incident as "an isolated incident and an annoying misunderstanding.[53]

The publication of these photographs continues up to this day, among them "The Origins of Evil. The Secret of Communism" and IPV News USA.[54] The original source of this photo is from the Album of Illustrations La famine en Russie, which was published in Geneva in 1922 in French and Russian.[55]

Estimation of the loss of life[]

- The 2004 book The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture, 1931–33 by R. W. Davies and Stephen G. Wheatcroft gives an estimate of 5.5 to 6.5 million deaths.[56]

- The Encyclopædia Britannica estimates that 6 to 8 million people died from hunger in the Soviet Union during this period, of whom 4 to 5 million were Ukrainians.[57] According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, "Some 4 to 5 million died in Ukraine, and another 2 to 3 million in the North Caucasus and the Lower Volga area."[58]

- Robert Conquest estimated at least 7 million peasants' deaths from hunger in the European part of the Soviet Union in 1932–33 (5 million in Ukraine, 1 million in the North Caucasus, and 1 million elsewhere), and an additional 1 million deaths from hunger as a result of collectivization in Kazakh ASSR.[59]

- Another study by Michael Ellman using data given by Davies and Wheatcroft estimates "'about eight and a half million' victims of famine and repression" combined in the period 1930–1933.[35]

- In his 2010 book Stalin's Genocides, Norman Naimark estimates that 3 to 5 million Ukrainians died in the famine.[21]

- In 2008, the Russian State Duma issued a statement about the famine, stating that within territories of Povolzhe, Central Black Earth Region, Northern Caucasus, Ural, Crimea, Western Siberia, Kazakhstan, Ukraine, and Belarus the estimated death toll is about 7 million people.[60]

See also[]

- Droughts and famines in Russia and the Soviet Union

- Holodomor genocide question

- Mass killings under communist regimes

Notes[]

References[]

- ^ Markoff, Alexandr Pavlovich (1933). "Famine in the USSR" (pdf). Bulletin Économique Russe (in French). Russian Commercial Institute. 9. Retrieved April 18, 2016.

- ^ Engerman, David (2009). Modernization from the Other Shore. ISBN 978-0674036529 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Famine on the South Siberia". Human Science. RU. 2 (98): 15.

- ^ "Demographic aftermath of the famine in Kazakhstan". Weekly. RU. Jan 1, 2003.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Наливайченко назвал количество жертв голодомора в Украине [Nalyvaichenko called the number of victims of Holodomor in Ukraine] (in Russian). LB.ua. 14 January 2010. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ^ "The U.S.S.R. from the death of Lenin to the death of Stalin – The Party versus the peasants". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Niccolò Pianciola (2001). "The Collectivization Famine in Kazakhstan, 1931–1933". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 25 (3–4): 237–251. JSTOR 41036834. PMID 20034146.

- ^ Volkava, Elena (2012-03-26). "The Kazakh Famine of 1930–33 and the Politics of History in the Post-Soviet Space". Wilson Center. Retrieved 2015-07-09.

- ^ Татимов М. Б. Социальная обусловленность демографических процессов. Алма-Ата, 1989. С.124

- ^ "Famine of 1932 | Soviet history". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-02-04.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Welsh journalist who exposed a Soviet tragedy". walesonline.com. November 13, 2009. Retrieved April 7, 2016.

- ^ Brown, Mark (November 12, 2009). "1930s journalist Gareth Jones to have story retold: Correspondent who exposed Soviet Ukraine's manmade famine to be focus of new documentary". The Guardian. London. Retrieved April 7, 2016.

- ^ "Yulia Tymoshenko: our duty is to protect the memory of the Holodomor victims". Tymoshenko's official website. 27 November 2010. Archived from the original on 2010-11-29. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ^ Naimark 2010, p. 70.

- ^ "Harper accused of exaggerating Ukrainian genocide death toll". MontrealGazette.com. 30 October 2010. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ^ David R. Marples. Heroes and Villains: Creating National History in Contemporary Ukraine. p. 50

- ^ Graziosi, A, Hajda, Lubomyr, editor of compilation & Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute, host institution 2013, After the Holodomor: The Enduring Impact of the Great Famine on Ukraine.

- ^ Conquest, Robert (1986). The Harvest Sorrow. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0195051803.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Naimark, Norman M (2010), Stalin's Genocides (Human Rights and Crimes against Humanity), Princeton University Press, p. 131, ISBN 978-0-691-14784-0.

- ^ "International Recognition of the Holodomor". Holodomor Education. Archived from the original on 31 December 2015. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ^ Sabol, Steven (2017). "The Touch of Civilization": Comparing American and Russian Internal Colonization. University Press of Colorado. p. 47. ISBN 978-1607325505.

- ^ Marples, David R. (May 2009). "Ethnic Issues in the Famine of 1932–1933 in Ukraine". Europe-Asia Studies. 61 (3): 505–518 [507]. doi:10.1080/09668130902753325. S2CID 67783643.

Geoffrey A. Hosking concluded that: Conquest’s research establishes beyond doubt, however, that the famine was deliberately inflicted there [in Ukraine] for ethnic reasons...Craig Whitney, however, disagreed with the theory of genocide

- ^ http://world.lib.ru/p/professor_l_k/070102_koval_drujba.shtml – "Запомнил и долю казахов в пределах своей республики – 28%. А за тридцать лет до того они составляли у себя дома уверенное большинство"

- ^ Pianciola, Niccolò (1 January 2001). "The Collectivization Famine in Kazakhstan, 1931–1933". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 25 (3/4): 237–251. JSTOR 41036834. PMID 20034146.

- ^ , Голод 1932–1933 годов. Трагедия российской деревни, Moscow, Росспэн, 2008, ISBN 978-5-8243-0987-4., Chapter 6. "Голод 1932–1933 годов в контексте мировых голодных бедствий и голодных лет в истории России – СССР", p. 331.

- ^ Mark B. Tauger. "Natural Disaster and Human Actions in the Soviet Famine of 1931–1933" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-08-24. Retrieved 2013-01-27. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Orlando Figes. The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin's Russia, Metropolitan Books, 2007, p. 240. ISBN 0805074619

- ^ "Internal Workings of the Soviet Union – Revelations from the Russian Archives". Library of Congress. 15 June 1992. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "The Soviet Famine of 1931–33: Politically Motivated or Ecological Disaster?". www.international.ucla.edu. Retrieved 2015-05-07.

- ^ Davies, Robert; Wheatcroft, Stephen (2009). The years of hunger: Soviet agriculture, 1931–1933. 5. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780333311073.

- ^ Marples, David (July 14, 2002). "Analysis: Debating the undebatable? Ukraine Famine of 1932-1933". The Ukrainian Weekly. LXX (28).

- ^ Siegelbaum, Lewis H. (17 June 2015). "Collectivization". Seventeen Moments in Soviet History. Michigan State University. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ellman, Michael (September 2005). "The Role of Leadership Perceptions and of Intent in the Soviet Famine of 1931–1934" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 57 (6): 823–41. doi:10.1080/09668130500199392. S2CID 13880089. Retrieved 2008-07-04.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lyons, Eugene (1938). Assignment in Utopia. Transaction Publishers. p. 573. ISBN 978-1-4128-1760-8.

- ^ Walter Duranty (31 March 1933). "RUSSIANS HUNGRY, BUT NOT STARVING; Deaths From Diseases Due to Malnutrition High, Yet the Soviet Is Entrenched". The New York Times: 13. Archived from the original on 2003-03-30.

- ^ Taylor, Sally J. (1990). Stalin's Apologist. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-505700-3.

- ^ Shipton, Martin (June 20, 2013). "Welsh journalist hailed one of greatest 'eyewitnesses of truth' for exposing '30s Soviet famine". Wales Online.

- ^ Mikhail Sergeevich Gorbachev (2006). Manifesto for the Earth: Action Now for Peace, Global Justice and a Sustainable Future. Clairview Books. p. 10. ISBN 1-905570-02-3

- ^ Obenson, Tambay A. (July 23, 2015). "140 New Projects Selected for the IFP's 2015 Project Forum Slate". indiewire.com. Retrieved April 7, 2016.

- ^ Colley, Philip. "The True Story behind the 'True Story' of Mr Jones". www.garethjones.org. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ellman, Michael (2007). "Stalin and the Soviet famine of 1932–33 Revisited". Europe-Asia Studies. 59 (4): 663–693. doi:10.1080/09668130701291899. S2CID 53655536.

- ^ http://www.un.org/ar/preventgenocide/adviser/pdf/osapg_analysis_framework.pdf

- ^ "Ukraine - World War I and the struggle for independence".

- ^ Applebaum, Anne (2017). Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine. Penguin. ISBN 978-0141978284.

- ^ Morgan, Lesa. "'Remember the peasantry': A study of genocide, famine, and the Stalinist Holodomor in Soviet Ukraine, 1932–33, as it was remembered by post-war immigrants in Western Australia who experienced it".

- ^ Getty, J. Arch (2000). "The Future Did Not Work". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

Similarly, the overwhelming weight of opinion among scholars working in the new archives (including Courtois's co-editor Werth) is that the terrible famine of the 1930s was the result of Stalinist bungling and rigidity rather than some genocidal plan.

- ^ Wheatcroft, Stephen (2018). "The Turn Away from Economic Explanations for Soviet Famines". Contemporary European History. 27 (3): 465–469. doi:10.1017/S0960777318000358.

- ^ Davies, Robert; Wheatcroft, Stephen (2009). The Industrialisation of Soviet Russia Volume 5: The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture 1931–1933. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. xiv. ISBN 978-0-230-27397-9.

- ^ Tauger, Mark (July 1, 2018). "Review of Anne Applebaum's 'Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine'". History News Network. Retrieved October 22, 2019.

- ^ The Foreign Office and the Famine: British Documents on Ukraine and the Great Famine of 1932—1933 / edited by Marco Carynnyk, Lubomyr Y. Luciuk and Bohdan S. Kordan; with a foreword by Michael R. Marrus. Kingston, Ont.; Vestal, N.Y. : Limestone Press, 1988. lxi, 493 p.; 24 cm. ISBN 0-919642-31-4

- ^ The head of the SBU admitted that photographs from the United States were used at the exhibition about the Holodomor // Regnum

- ^ With a camera around the GULAG Archived 2007-09-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ La famine en Russie Album Illustre, Livraison No. 1, Geneva, Comite Russe de Secours aux Affames en Russie, 1922.

- ^ Davies & Wheatcroft 2004, p. 401.

- ^ "Ukraine – The famine of 1932–33". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ^ "The Party versus the peasants". www.britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- ^ Conquest, Robert (1986), The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine, Oxford University Press, p. 306, ISBN 978-0-19-505180-3.

- ^

Works related to Soviet famine of 1930s at Wikisource

Works related to Soviet famine of 1930s at Wikisource

Sources[]

- Davies, RW; Wheatcroft, SG (2004), The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture, 1931–33; Harrison, Davies, Wheatcroft 2004 (PDF) (review), UK: Warwick.

- Ellman, Michael (June 2007), "Stalin and the Soviet Famine of 1932–33 Revisited" (PDF), Europe-Asia Studies, 59 (4): 663–93, doi:10.1080/09668130701291899, S2CID 53655536.

- Finn, Peter (April 27, 2008), "Aftermath of a Soviet Famine", The Washington Post.

- Kuromiya, Hiroaki (June 2008), "The Soviet Famine of 1932–1933 Reconsidered", Europe-Asia Studies, 60 (4): 663–75, doi:10.1080/09668130801999912, S2CID 143876370.

- Kindler, Robert, Stalin's Nomads. Power and Famine in Kazakhstan, Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh University Press, 2018.

- Luciuk, Lubomyr Y, ed, Holodomor: Reflections on the Great Famine in Soviet Ukraine, Kingston, Kashtan Press, 2008

- Markoff, A (1933), Famine in USSR.

- Snyder, Timothy (2010). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. London: The Bodley Head. ISBN 978-0-224-08141-2.

- Thorson, Carla (May 5, 2003), The Soviet Famine of 1931–33: Politically Motivated or Ecological Disaster?, UCLA International Institute.

- Wheatcroft, SG (April 1990), "More light on the scale of repression and excess mortality in the Soviet Union in the 1930s" (PDF), Soviet Studies, 42 (2): 355–367, doi:10.1080/09668139008411872.

- Kondrashin, Viktor, ed. (2009), Famine in the Soviet Union 1929–1934 (PDF) (slide stack), Katz, Nikita B transl. docs.; Dolgova, Alexandra transl. note from compilers; Glizchinskaya, Natalia design, RU: Russian Archives, archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-19.

External links[]

- Sokolova, S. (2019). "Technology of Soviet Myth Creation about Famine as a Result of Crop Failure in Ukraine of the 1932–1933s". Journal of Modern Science. 42 (3): 37-56. doi:10.13166/jms/113374.

- 1930s in Belarus

- 1932 in Europe

- 1933 in Europe

- 1932 in the Soviet Union

- 1933 in the Soviet Union

- 20th-century famines

- Famines in Russia

- Famines in the Soviet Union

- Joseph Stalin