Sterling Price

Sterling Price | |

|---|---|

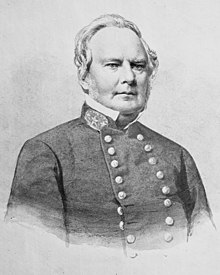

Price in uniform, c. 1862 | |

| Nickname(s) | "Old Pap" |

| Born | September 14, 1809 Prince Edward County, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | September 29, 1867 (aged 58) St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. |

| Buried | Bellefontaine Cemetery, 38°41′29″N 90°13′49″W / 38.69139°N 90.23028°WSt. Louis, Missouri, U.S. |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1846–1848 (USV) 1861 (MSG) 1861–1865 (CSA) |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | Missouri Mormon War

American Civil War

|

| Spouse(s) | Martha Head (m. 1833) |

| Children |

|

| Relations |

|

| Other work | Commission merchant |

| 11th Governor of Missouri | |

| In office January 3, 1853 – January 5, 1857 | |

| Preceded by | Austin A. King |

| Succeeded by | Trusten Polk |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Missouri's 3rd district | |

| In office March 4, 1845 – August 12, 1846 | |

| Preceded by | John Jameson |

| Succeeded by | William McDaniel |

Major-General Sterling Price (September 14, 1809 – September 29, 1867) was a senior officer of the Confederate States Army who fought in both the Western and Trans-Mississippi theaters of the American Civil War. He rose to prominence during the Mexican–American War and served as governor of Missouri from 1853 to 1857. He is remembered today for his service in Arkansas (1862–1865) and for his defeat at the Battle of Westport on October 23, 1864.

Early life and education[]

Sterling Price was born near Farmville, in Prince Edward County, Virginia on September 14, 1809,[1] into a family of Welsh origin. His father was Pugh Price, whose ancestor John Price[2] was born in Brecknock, Wales, in 1584 and settled in the Virginia Colony in the early 1600s. His mother was Elizabeth Williamson. Price attended Hampden–Sydney College in 1826 and 1827,[3] studying law and working at the courthouse near his home. He was admitted to the Virginia bar and opened a law practice.

In the fall of 1831, Price moved with his family to Fayette, Missouri. A year later, they moved to Keytesville, Missouri, where he ran a hotel and mercantile business. On May 14, 1833, he married Martha Head of Randolph County, Missouri. They had seven children, five surviving to adulthood:[4] Edwin Williamson, Herber, Celsus, Martha Sterling, and Quintus.

Price was elected to the Missouri State House of Representatives, serving one term from 1836 to 1838, and again for two terms from 1840 to 1844. During the latter terms, he was chosen as its speaker. He was elected as a Democrat to the 29th United States Congress, serving from March 4, 1845, to August 12, 1846, when he resigned from the House to serve in the Mexican–American War.[3]

Missouri Mormon War[]

During the Missouri Mormon War, Price served as a member of a delegation sent from Chariton County to investigate reported disturbances between the Latter Day Saints and anti-Mormon mobs. His report was favorable to the Mormons, stating they were not guilty of any offenses and that in his opinion the charges had been brought by their enemies.[5] Following the Mormon capitulation in November 1838, Missouri governor Lilburn Boggs ordered Price to lead a company of men to protect the Mormons from further depredations.[6]

Mexican–American War[]

Price raised the Second Regiment, Missouri Mounted Volunteer Cavalry and was appointed as its colonel on August 12, 1846.[7] He marched his regiment under Alexander Doniphan to Santa Fe, where he assumed command of the Territory of New Mexico after Gen. Stephen W. Kearny, departed for California. Price served as military governor of New Mexico, and put down the Taos Revolt in January 1847, an uprising of Native Americans and Mexicans.

President James K. Polk promoted Price to brigadier general of volunteers on July 20, 1847.[7] He was named military governor of Chihuahua that same month. He led 300 men from his Army of the West at the Battle of Santa Cruz de Rosales on March 16, 1848, defeating a Mexican force three times his size.[3] This was the last battle of the war, taking place days after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo had been ratified by the United States Congress on March 10. Although reprimanded by Secretary of War William L. Marcy and ordered to return with his army to New Mexico, Price was not punished. He was honorably discharged on November 25, 1848, and returned to Missouri as a hero.[8]

Governor of Missouri[]

Price became a slave owner and planter, cultivating tobacco on the Bowling Green prairie. Popular because of his war service, he was easily elected Governor of Missouri in 1852, serving from 1853 to 1857. During his tenure, Washington University in St. Louis was established, the state's public school system was restructured, the Missouri State Teachers Association was created, the state's railroad network was expanded, and a state geological survey was created.[9] Although the state legislature passed an act to increase the governor's salary, Price refused to accept anything more than the salary for which he had been elected.[10] Price was appointed as the state's Bank Commissioner, serving from 1857 to 1861. He also secured a rail line through his home county, which became part of the Norfolk and Western Railway.

American Civil War[]

Struggle for Missouri[]

Price was initially a strong supporter of the Union. He backed Stephen A. Douglas for president in 1860.[11] When the states of the Deep South seceded and formed the Confederate States of America, Price opposed secession by Missouri. He was elected presiding officer of the Missouri State Convention on February 28, 1861, which voted against the state leaving the Union. The situation changed markedly, however, when pro-Union Francis Preston Blair, Jr. and Capt. Nathaniel Lyon seized the state militia's Camp Jackson at St. Louis. Outraged by this virtual declaration of war against the state, Price gave his support to the secessionists.

Pro-Confederate Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson appointed him to command the newly reformed Missouri State Guard in May 1861, and Price led his recruits (who nicknamed him "Old Pap") in a campaign to expel Lyon's troops. By then Lyon had seized the state capital and pushed through a bill to remove Governor Jackson from office and replace him with an unelected Union governor. The climax of the conflict was the Battle of Wilson's Creek, fought on August 10, where Price's Missouri State Guard, supported by Confederate troops led by Brigadier General Benjamin McCulloch, soundly defeated Lyon's Army of the West; the Union general was killed during the battle.[12] Price's troops launched an offensive into northern Missouri, defeating the Federal forces of Colonel James Mulligan at the First Battle of Lexington. However, the Union Army soon sent reinforcements to Missouri, and forced Price's men and Governor Jackson to fall back to the Arkansas border. The Union retained control of most of Missouri for the remainder of the war, although there were frequent guerrilla raids in the western sections.

Still operating as a Missouri militia general (rather than as a commissioned Confederate officer), Price was unable to agree with his Wilson's Creek colleague, Brigadier General Benjamin McCulloch, as to how to proceed following the battle. This resulted in the splitting of what might otherwise have become a sizable Confederate force in the West. Price and McCulloch became such bitter rivals that the Confederacy appointed Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn as overall commander of the Trans-Mississippi district. Van Dorn reunited Price's and McCulloch's formations into a force he named the Army of the West, and set out to engage Unionist troops in Missouri under the command of Brig. Gen. Samuel R. Curtis. Now under Van Dorn's command, Price was commissioned in the Confederate States Army as a major general on March 6, 1862.[7]

Outnumbering Curtis's forces, Van Dorn attacked the Northern army at Pea Ridge on March 7–8. Although wounded in the fray, Price pushed Curtis's force back at Elkhorn Tavern on March 7, but the battle was lost on the following day after a furious Federal counterattack.

Western Theater[]

Price, now serving under Van Dorn, crossed the Mississippi River to reinforce Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard's army in northern Mississippi following Beauregard's loss at the Battle of Shiloh. Van Dorn's army was positioned on the Confederate right flank during the Siege of Corinth. During Braxton Bragg's Confederate Heartland Offensive, Van Dorn was sent to western Mississippi, while Price given command of the District of Tennessee. As Bragg marched his army into Kentucky, Bragg urged Price to make some move to assist him. Not waiting to re-unite with Van Dorn's returning forces, Price seized the Union supply depot at nearby Iuka, but was driven back by Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans at the Battle of Iuka on September 19, 1862. A few weeks later, on October 3–4, Price (under Van Dorn's command once more) was defeated with Van Dorn at the Second Battle of Corinth.

Van Dorn was replaced by Maj. Gen. John C. Pemberton, and Price, who had become thoroughly disgusted with Van Dorn and was eager to return to Missouri, obtained a leave to visit Richmond, the Confederate capital. There, he obtained an audience with Confederate President Jefferson Davis to discuss his grievances, only to find his own loyalty to the South sternly questioned by the Confederate leader. Price did secure Davis's permission to return to Missouri—minus his troops. Unimpressed with the Missourian, Davis pronounced him "the vainest man I ever met."[8]

Trans-Mississippi Theater[]

Price was not finished as a Confederate commander, however. He contested Union control over Arkansas in the summer of 1863, and while he won some of his engagements, he was not able to dislodge Northern forces from the state, abandoning Little Rock for southern Arkansas.

Camden Expedition[]

In early 1864, Confederate General Edmund Kirby-Smith, in command of the Western Louisiana campaign, ordered General Price in Arkansas to send all of his infantry to Shreveport. Confederate forces in the Indian Territory were to join Price in the endeavor. General John B. Magruder in Texas was instructed to send infantry toward Marshall, Texas, west of Shreveport. General St. John R. Liddell was instructed to proceed from the Ouachita River west toward Natchitoches. With a force of five thousand, Price reached Shreveport on March 24. However, Kirby-Smith detained the division and divided it into two smaller ones. He hesitated to send the men south to fight Union General Nathaniel P. Banks, who he believed outnumbered the Confederate forces. This decision was opposed by General Richard Taylor. Price marched back into Arkansas to oppose General Frederick Steele's Camden Expedition but was defeated at the Battle of Prairie D'Ane and the Battle of Jenkin's Ferry. By this time, the western campaign was nearing its conclusion.[13]

Missouri Expedition[]

Despite his disappointments in Arkansas and Louisiana, Price convinced his superiors to permit him to invade Missouri in the fall of 1864, hoping yet to seize that state for the Confederacy or at the very least imperil Abraham Lincoln's chances for reelection that year. Confederate General Kirby Smith agreed, though he was forced to detach the infantry brigades originally detailed to Price's force and send them elsewhere, thus changing Price's proposed campaign from a full-scale invasion of Missouri to a large cavalry raid. Price amassed 12,000 horsemen for his army, and fourteen pieces of artillery.[14]

The first major engagement in Price's Raid occurred at Pilot Knob, where he successfully captured the Union-held Fort Davidson but needlessly subjected his men to high fatalities in the process, for a gain that turned out to be of no real value. From Pilot Knob, Price swung west, away from St. Louis (his primary objective) and toward Kansas City, Missouri and nearby Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Forced to bypass his secondary target at heavily fortified Jefferson City, Price cut a swath of destruction across his home state, even as his army steadily dwindled due to battlefield losses, disease, and desertion.

Although he defeated inferior Federal forces at Boonville, Glasgow, Lexington, the Little Blue River and Independence, Price was ultimately boxed in by two Northern armies at Westport, located in today's Kansas City, where he had to fight against overwhelming odds. This unequal contest, known afterward as "The Gettysburg of the West", did not go his way, and he was forced to retreat into hostile Kansas. A new series of defeats followed, as Price's battered and broken army was pushed steadily southward toward Arkansas, and then further south into Texas. Price's Raid was his last significant military operation, and the last significant Confederate campaign west of the Mississippi.

Notable battles[]

Some of Price's notable battles during the American Civil War are listed here in order of occurrence, and indicating whether he was in overall command and whether the battle or engagement was won or lost:

| Battle | Command | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Carthage, Missouri | not in command | won |

| Wilson's Creek, Missouri | not in command | won |

| Lexington, Missouri | in command | won |

| Pea Ridge, Arkansas | not in command | lost |

| Iuka, Mississippi | in command | lost |

| Corinth, Mississippi | not in command | lost |

| Helena, Arkansas | not in command | lost |

| Bayou Fourche, Arkansas | in overall command, though not commanding on the battlefield | lost |

| Prairie D'Ane, Arkansas | in command | lost |

| Jenkins' Ferry, Arkansas | not in command | lost: Confederates took the field, but the Union force escaped |

| Pilot Knob, Missouri | in command | lost: Price took the fort, but the Union force escaped |

| Glasgow, Missouri | in overall command, though not commanding on the battlefield | won |

| Little Blue River, Missouri | in command | won |

| Independence, Missouri | in command | won |

| Westport, Missouri | in command | lost |

| Mine Creek, Kansas | in command | lost |

Immigration to Mexico[]

Rather than surrender, Price emigrated to Mexico, where he and several of his former compatriots attempted to start a colony of Southerners. He settled in a Confederate exile colony in Carlota, Veracruz. There Price unsuccessfully sought service with the Emperor Maximilian. When the colony failed, he returned to Missouri.

Death and legacy[]

While in Mexico, Price started having severe intestinal problems, which grew worse in August 1866 when he contracted typhoid fever. Impoverished and in poor health, Price died of cholera (or "cholera-like symptoms") in St. Louis, Missouri. The death certificate listed the cause of death as "chronic diarrhea".[15] Price's funeral was held on October 3, 1867, in St. Louis, at the First Methodist Episcopal Church (on the corner of Eighth and Washington). His body was carried by a black hearse drawn by six matching black horses, and his funeral procession was the largest to take place in St. Louis up to that point. He was buried in Bellefontaine Cemetery.[16]

In his paper "Assessing Compound Warfare During Price's Raid", written as a thesis for the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, Major Dale E. Davis postulates that Price's Missouri Raid failed primarily due to his inability to properly employ the principles of "compound warfare". This requires an inferior power to effectively use regular and irregular forces in concert to defeat a superior army. He also blamed Price's slow rate of movement during his campaign, and the close proximity of Confederate irregulars to his regular force, for the defeat.

Davis observes that by wasting valuable time, ammunition and men in his relatively meaningless assaults on Fort Davidson, Glasgow, Sedalia and Boonville, Price offered Union General Rosecrans time he might not otherwise have had to organize an effective response. Furthermore, he says, Price's insistence on guarding an ever-expanding wagon train of looted military supplies and other items ultimately became "an albatross to [his] withdrawal".[17] Price, said Davis, ought to have used Confederate bushwhackers to harass Federal formations, forcing the Unionists to disperse significant numbers of troops to pursue them over wide ranges of territory—which in turn would have reduced the number of effectives available to fight against Price's main force. Instead, Price kept many guerrillas close to his army, even incorporating some into his ranks, largely negating the value represented by their mobility and small, independent formations. This in turn allowed Union generals to concentrate a force large enough to trap and defeat Price at Westport, effectively ending his campaign.

While the scope of Davis' research is limited to Price's Missouri expedition, it provides some insight into Price's tactical and strategic mindset, together with a sense of some of his strengths and weaknesses as a general. While devoted to the Southern cause, Price's goals in his Confederate military operations were directed to liberating his home state of Missouri. Although he achieved victories during all phases of the war, his strategically most important battles (other than Wilson's Creek) all ended in defeat.

Honors[]

- During the American Civil War, a wooden river steamer built at Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1856 as the Laurent Millaudon was taken into Confederate service and renamed the CSS General Sterling Price. Participating in actions near Fort Pillow, Tennessee on May 10, 1862, she damaged two Federal gunboats before being temporarily put out of action. The General Price was sunk during the Battle of Memphis, raised, repaired, and served in the Union Navy under the name USS General Price although she was still referred to as the "General Sterling Price" in Federal dispatches. As a Union ship, she served in the Vicksburg and Red River campaigns. The General Price was sold for private use after the war.[18]

- Camp No. 31 (organized October 13, 1889) of the United Confederate Veterans (UCV) in the city of Dallas, Texas, was named after him.[19]

- A monument to Price stands in the Springfield National Cemetery (Springfield, Missouri). Dedicated August 10, 1901, the bronze figure honors all Missouri soldiers and General Price. It was commissioned by the United Confederate Veterans of Missouri.

- A statue of Price stands in Price Park, Keytesville, Missouri, which is also the location of the Sterling Price Museum in his honor.

- The United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) commissioned Jorgen Dreyer in 1939 to create a bust of Price.[20] It is in the Visitor Center of the Battle of Lexington Missouri Historic Site.

- Camps No. 145 (St. Louis) and Camp No. 676 (Littleton, Colorado) of the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV) are named after him.

In popular culture[]

- The actor Willis Bouchey was cast as General Price in the 1957 episode, "Decision at Wilson's Creek," on the CBS western anthology series, Dick Powell's Zane Grey Theatre. John Forsythe played a Confederate lieutenant who suddenly quits the Army and returns to his wife, only to find that he is scorned by townspeople.[21]

- An orange tabby cat was named for him in the John Wayne movies, True Grit and Rooster Cogburn, as Cogburn's alcoholic cat.[22]

- Price is depicted as the villain of "Old Pap", an episode of The Pinkertons.[23]

See also[]

- List of American Civil War generals (Confederate)

- List of governors of Missouri

References[]

- ^ "Sterling Price", The National Cyclopedia of American Biography

- ^ Familysearch.org Archived December 12, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Dupuy, p. 612.

- ^ Dictionary of Missouri Biography (Univ. of Missouri Press, 1999).

- ^ LeSueur, Stephen C. The 1838 Mormon War in Missouri. University of Missouri Press, 1987. pp. 84–85.

- ^ LeSueur, p. 233.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Eicher, p. 440.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sterling Price. Retrieved on November 22, 2009.

- ^ Governor's Information: Sterling Price. Retrieved on November 22, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Pictorial and Genealogical Record of Greene County, Missouri, entry: "General Sterling Price"; The Library, Springfield, Missouri. Retrieved on November 24, 2009.

- ^ Pollard 1867, p. 155.

- ^ "The Battle of Wilson's Creek", Civil War Trust. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- ^ Winters, John D. (1963). The Civil War in Louisiana. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. pp. 328–329, 336, 361, 382. ISBN 0-8071-0834-0.

- ^ "Sterling Price (1809–1867)", The Latin Library. Retrieved on November 26, 2009.

- ^ Welsh, Jack D. (1995). Medical Histories of Confederate Generals. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. pp. 177. ISBN 0-87338-505-5.

- ^ Shalhope, Robert E. (1971). Sterling Price: Portrait of a Southerner. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. pp. xi, 290. ISBN 978-0-8262-0103-4.

- ^ Davis, Dale E. Assessing Compound Warfare During Price's Raid. Ft. Leavenworth: U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, 2004, p. 55.

- ^ History of the ship, CSS General Sterling Price

- ^ Charter, constitution and by-laws, officers and members of Sterling Price Camp, United Confederate Veterans, Camp No. 31: organized, October 13, 1889, in the city of Dallas, Texas. published 1893, hosted by the Portal to Texas History.

- ^ Sedalia (MO) Democrat, p. 10, September 17, 1939.

- ^ ""Decision at Wilson's Creek" on Dick Powell's Zane Grey Theatre". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ General Sterling Price at IMDb

- ^ ""The Pinkertons" Old Pap (TV Episode 2015) - IMDb".

Sources[]

- Davis, Dale E. Assessing Compound Warfare During Price's Raid. Ft. Leavenworth, KS: U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, 2004. OCLC 70153559.

- Dupuy, Trevor N., Curt Johnson, and David L. Bongard. Harper Encyclopedia of Military Biography. New York: HarperCollins, 1992. ISBN 978-0-06-270015-5.

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher, Civil War High Commands. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1.

- Gifford, Douglas L. The Battle of Pilot Knob: Staff Ride and Battlefield Tour Guide. Winfield, MO: D.L. Gifford, 2003. ISBN 978-1-59196-478-0.

- LeSueur, Stephen C. The 1838 Mormon War in Missouri. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1987. ISBN 978-0-8262-6103-8.

- Lexington Historical Society. The Battle of Lexington, .... Lexington, MO: Lexington Historical Society, 1903. OCLC 631462805.

- Pollard, Edward A. (1867) [1866]. The Lost Cause: A New Southern History of the War of the Confederates: Comprising a Full and Authentic Account of the Rise and Progress of the Late Southern Confederacy--the Campaigns, Battles, Incidents, and Adventures of the Most Gigantic Struggle of the World's History. New York, NY: E.B. Treat & Co., Publishers. ISBN 9780517101315.

- Rea, Ralph R. Sterling Price, the Lee of the West. Little Rock, AR: Pioneer Press, 1959. OCLC 2626512.

- Sifakis, Stewart. Who Was Who in the Civil War. New York: Facts On File, 1988. ISBN 978-0-8160-1055-4.

- Twitchell, Ralph Emerson. The History of the Military Occupation of the Territory of New Mexico from 1846 to 1851. Denver, CO: Smith-Brooks Company Publishers, 1909. OCLC 2693546.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. ISBN 978-0-8071-0823-9.

Further reading[]

- Castel, Albert. General Sterling Price and the Civil War in the West. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press, 1968. ISBN 0-8071-1854-0.

- Forsyth, Michael J. The Great Missouri Raid: Sterling Price and the Last Major Confederate Campaign in Northern Territory (McFarland, 2015) viii, 282 pp.

- Geiger, Mark W. (2010). Financial Fraud and Guerrilla Violence in Missouri's Civil War, 1861–1865. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-15151-0.

- Shalhope, Robert E. Sterling Price, Portrait of a Southerner. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press, 1971.

- Sinisi, Kyle S. The Last Hurrah: Sterling Price's Missouri Expedition of 1864 (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015.) xviii, 432 pp.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sterling Price. |

- Sterling Price at Find a Grave

- Sterling Price at The Historical Marker Database (HMdb.org)

- Sterling Price at the National Governors Association

- Sterling Price at The Political Graveyard

- Sterling Price Camp No. 145 of the Sons of Confederate Veterans

- United States Congress. "Sterling Price (id: P000531)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Works by or about Sterling Price at Internet Archive

- Works by or about Sterling Price in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- 1809 births

- 1867 deaths

- 19th-century American politicians

- American military personnel of the Mexican–American War

- American expatriates in Mexico

- American people of Welsh descent

- American refugees

- Arkansas in the American Civil War

- Burials at Bellefontaine Cemetery

- Confederate expatriates

- Confederate States Army major generals

- Deaths from cholera

- Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives

- Democratic Party state governors of the United States

- Governors of Missouri

- Hampden–Sydney College alumni

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from Missouri

- Missouri State Guard

- People from Bowling Green, Missouri

- People from Keytesville, Missouri

- People from Prince Edward County, Virginia

- People of Missouri in the American Civil War

- Refugees in Mexico

- Speakers of the Missouri House of Representatives

- People of the Taos Revolt

- American slave owners