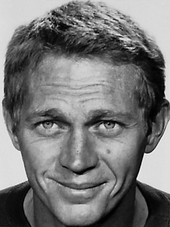

Steve McQueen

Steve McQueen | |

|---|---|

McQueen in The Thomas Crown Affair (1968) | |

| Born | March 24, 1930 Beech Grove, Indiana, U.S. |

| Died | November 7, 1980 (aged 50) Ciudad Juárez, Mexico |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1952–1980 |

| Spouse(s) | Ali MacGraw

(m. 1973; div. 1978) |

| Children | 2, including Chad McQueen[3] |

| Relatives | Steven R. McQueen (grandson) |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1946 (Merchant Marine) 1947–1950 (USMC) |

| Rank | |

Terrence Stephen McQueen (March 24, 1930 – November 7, 1980),[4] nicknamed the "King of Cool", was an American actor. His antihero persona, emphasized during the height of the counterculture of the 1960s, made him a top box-office draw during the 1960s and 1970s.

McQueen received an Academy Award nomination for his role in The Sand Pebbles (1966). His other popular films include Love With the Proper Stranger (1963), The Cincinnati Kid (1965), Nevada Smith (1966), The Thomas Crown Affair (1968), Bullitt (1968), Le Mans (1971), The Getaway (1972) and Papillon (1973), as well as the all-star ensemble films The Magnificent Seven (1960), The Great Escape (1963) and The Towering Inferno (1974).

In 1974, McQueen became the highest-paid movie star in the world, although he did not act in film for another four years. He was combative with directors and producers, but his popularity placed him in high demand and enabled him to command the largest salaries.[5]

Early life[]

Terrence Stephen McQueen was born on March 24, 1930, at St. Francis Hospital in Beech Grove, Indiana, a suburb of Indianapolis.[6][7][8] McQueen, of Scottish descent, was raised a Roman Catholic.[9][10] His father, William McQueen, a stunt pilot for a barnstorming flying circus, left McQueen's mother, Julia Ann (a.k.a. Julian; née Crawford),[6][11]:9 six months after meeting her.[7][12] Several biographers have stated that Julia Ann was an alcoholic.[11]:72[13][14]:7–8[15] Unable to cope with caring for a small child, she left him with her parents (Victor and Lillian) in Slater, Missouri, in 1933. As the Great Depression set in shortly thereafter, McQueen and his grandparents moved in with Lillian's brother Claude at his farm in Slater.[7] McQueen expressed having good memories of living on the farm, noting that his great-uncle Claude "was a very good man, very strong, very fair. I learned a lot from him."[7]

Claude gave McQueen a red tricycle on his fourth birthday, a gift that McQueen subsequently credited with sparking his early interest in racing.[7] At the age of eight, he was taken to Indianapolis by his mother, who lived there with her new husband. McQueen's departure from his great-uncle's home was marked by a very special memento given to him on that occasion. "The day I left the farm", he recalled, "Uncle Claude gave me a personal going-away present—a gold pocket watch, with an inscription inside the case." The inscription read "To Steve – who has been a son to me."[14]

Dyslexic and partially deaf due to a childhood ear infection,[7] McQueen did not adjust well to his new life. His new stepfather beat him to such an extent that at the age of nine he left home to live on the streets.[13] He later recalled "When a kid doesn't have any love when he's small, he begins to wonder if he's good enough. My mother didn't love me, and I didn't have a father. I thought, 'Well, I must not be very good.'"[16] Soon he was running with a street gang and committing acts of petty crime.[7] Unable to control his behavior, his mother sent him back to Slater. When he was 12, Julia wrote to Claude, asking that her son be returned to her again to live in her new home in Los Angeles, California. Julia's second marriage had ended in divorce, and she had married a third time.[citation needed]

By McQueen's own account, he and his new stepfather "locked horns immediately".[7] McQueen recalls him being "a prime son of a bitch" who was not averse to using his fists on McQueen and his mother.[7] As McQueen began to rebel again, he was sent back to live with Claude for a final time.[7] At age 14, he left Claude's farm without saying goodbye and joined a circus for a short time,[7] then drifted back to his mother and stepfather in Los Angeles—resuming his life as a gang member and petty criminal.[17] McQueen was caught stealing hubcaps by the police and handed over to his stepfather, who beat him severely, ending the fight by throwing McQueen down a flight of stairs. McQueen looked up at his stepfather and said, "You lay your stinking hands on me again and I swear, I'll kill you."[7]

After the incident, McQueen's stepfather persuaded his mother to sign a court order stating that McQueen was incorrigible, remanding him to the California Junior Boys Republic in Chino.[7] Here, McQueen began to change and mature. He was not popular with the other boys at first: "Say the boys had a chance once a month to load into a bus and go into town to see a movie. And they lost out because one guy in the bungalow didn't get his work done right. Well, you can pretty well guess they're gonna have something to say about that. I paid my dues with the other fellows quite a few times. I got my lumps, no doubt about it. The other guys in the bungalow had ways of paying you back for interfering with their well-being."[18] Ultimately McQueen became a role model and was elected to the Boys Council, a group who set the rules and regulations governing the boys' lives.[7] He eventually left the Boys Republic at age 16. When he later became famous, he regularly returned to talk to the boys and retained a lifelong association.[19]

At age 16, McQueen left Chino Hills and returned to his mother, now living in Greenwich Village, New York. He then met two sailors from the Merchant Marine and volunteered to serve on a ship bound for the Dominican Republic.[7] Once there, he abandoned his new post, eventually being employed in a brothel;[13] afterwards, McQueen made his way to Texas and drifted from job to job including selling pens at a traveling carnival, working as a lumberjack in Canada, and a 30-day assignment on a chain gang in the Deep South for vagrancy.[20]

Military service[]

In 1947, after receiving permission from his mother since he was not yet 18 years old, McQueen enlisted in the Marines and was sent to Parris Island for boot camp.[2]:106[21][22] He was promoted to private first class and assigned to an armored unit.[7] He initially reverted to his prior rebelliousness and was demoted to private seven times. He took an unauthorized absence by failing to return after a weekend pass expired, staying with a girlfriend for two weeks until the shore patrol caught him. He resisted arrest and spent 41 days in the brig.[7] After this, he resolved to focus his energies on self-improvement and embraced the Marines' discipline. He saved the lives of five other Marines during an Arctic exercise, pulling them from a tank before it broke through ice into the sea.[7][23] He was assigned to the honor guard responsible for guarding the presidential yacht of US President Harry Truman.[7] McQueen served until 1950, when he was honorably discharged.[2]:106[21][22] He later said he had enjoyed his time in the Marines.[24] He remembered the Marines as a formative time in his life, saying, "The Marines made a man out of me. I learned how to get along with others, and I had a platform to jump off of."[25]

Acting[]

The 1950s[]

In 1952, with financial assistance provided by the G.I. Bill, McQueen began studying acting in New York at Sanford Meisner's Neighborhood Playhouse and at HB Studio[26] under Uta Hagen.[7] Reportedly, he delivered his first dialogue on a theatre stage in a 1952 play produced by Yiddish theatre star Molly Picon. McQueen's character spoke one brief line: "Alts iz farloyrn." ("All is lost.").[27] During this time, he also studied acting with Stella Adler, in whose class he met Gia Scala.[28]

McQueen began to earn money by competing in weekend motorcycle races at Long Island City Raceway and purchased the first two of many motorcycles, a Harley-Davidson and a Triumph.[12] He soon became an excellent racer and went home each weekend with about $100 in winnings (equivalent to $1,000 in 2020).[7][29] He appeared as a musical judge in an episode of ABC's Jukebox Jury that aired in the 1953–1954 season.[30]

McQueen had minor roles in productions, including Peg o' My Heart, The Member of the Wedding, and Two Fingers of Pride. He made his Broadway debut in 1955 in the play A Hatful of Rain, starring Ben Gazzara.[7]

In late 1955 at the age of 25, McQueen left New York and headed for California, where he moved into a house on Vestal Avenue in the Echo Park area, seeking acting jobs in Hollywood.[31] When McQueen appeared in a two-part Westinghouse Studio One television presentation entitled The Defenders, Hollywood manager Hilly Elkins (who managed McQueen's first wife, Neile) took note of him[32] and decided that B-movies would be a good place for the young actor to make his mark. He landed his first film role in a bit part in Somebody Up There Likes Me, directed by Robert Wise and starring Paul Newman. McQueen was subsequently hired for the films Never Love a Stranger; The Blob (his first leading role), which depicts a flesh-eating amoeba-like space creature; and The Great St. Louis Bank Robbery.

McQueen's first breakout role came on television. He appeared on Dale Robertson's NBC western series Tales of Wells Fargo as Bill Longley. Elkins, then McQueen's manager, successfully lobbied Vincent M. Fennelly, producer of the western series Trackdown, to have McQueen read for the part of bounty hunter Josh Randall, first appearing in Season 1 Episode 21 of Trackdown in 1958. He appeared as Randall in that episode, cast opposite series lead and old New York motorcycle racing buddy Robert Culp. McQueen appeared again on Trackdown in Episode 31 of the first season, but not as Josh Randall. In that episode, he played twin brothers, one of whom was an outlaw sought by Culp's character, Hoby Gilman. McQueen then filmed a pilot episode for what became the series titled Wanted: Dead or Alive, which aired on CBS in September 1958.

The 1960s[]

In the interviews in the DVD release of Wanted, Trackdown star Robert Culp claims credit for bringing McQueen to Hollywood and landing him the part of Randall. He said he taught McQueen the "art of the fast-draw," adding that, on the second day of filming, McQueen beat him. McQueen became a household name as a result of this series.[7] Randall's special holster held a sawed-off .44–40 Winchester rifle nicknamed the "Mare's Leg" instead of the six-gun carried by the typical Western character, although the cartridges in the gunbelt were dummy .45–70, chosen because they "looked tougher." Coupled with the generally negative image of the bounty hunter (noted in the three-part DVD special on the background of the series), this added to the antihero image infused with mystery and detachment that made this show stand out from the typical TV Western. The 94 episodes that ran from 1958 until early 1961 kept McQueen steadily employed, and he became a fixture at the renowned Iverson Movie Ranch in Chatsworth, where much of the outdoor action for Wanted: Dead or Alive was shot.

At 29, McQueen got a significant break when Frank Sinatra removed Sammy Davis Jr. from the film Never So Few after Davis supposedly made some mildly negative remarks about Sinatra in a radio interview, and Davis's role went to McQueen. Sinatra saw something special in McQueen and ensured that the young actor got plenty of closeups in a role that earned McQueen favorable reviews. McQueen's character, Bill Ringa, was never more comfortable than when driving at high speed—in this case in a jeep—or handling a switchblade or a tommy gun.

After Never So Few, the film's director John Sturges cast McQueen in his next movie, promising to "give him the camera". The Magnificent Seven (1960), in which he played Vin Tanner and co-starred with Yul Brynner, Eli Wallach, Robert Vaughn, Charles Bronson, Horst Buchholz and James Coburn, became McQueen's first major hit and led to his withdrawal from Wanted: Dead or Alive. McQueen's focused portrayal of the taciturn second lead catapulted his career. His added touches in many of the shots, such as shaking a shotgun round before loading it, repeatedly checking his gun while in the background of a shot, and wiping his hat rim, annoyed costar Brynner, who protested that McQueen was trying to steal scenes.[7] (In his autobiography,[33] Eli Wallach reports struggling to conceal his amusement while watching the filming of the funeral-procession scene where Brynner's and McQueen's characters first meet: Brynner was furious at McQueen's shotgun-round-shake, which effectively diverted the viewer's attention to McQueen.) Brynner refused to draw his gun in the same scene with McQueen, not wanting his character outdrawn.[7]

McQueen played the top-billed lead role in the next big Sturges film, 1963's The Great Escape, Hollywood's fictional depiction of the true story of a historic mass escape from a World War II POW camp, Stalag Luft III. Insurance concerns prevented McQueen from performing the film's notable motorcycle leap, which was done by his friend and fellow cycle enthusiast Bud Ekins, who resembled McQueen from a distance.[34] When Johnny Carson later tried to congratulate McQueen for the jump during a broadcast of The Tonight Show, McQueen said, "It wasn't me. That was Bud Ekins." This film established McQueen's box-office clout and secured his status as a superstar.[35]

Also in 1963, McQueen starred in Love with the Proper Stranger with Natalie Wood. He later appeared as the titular Nevada Smith, a character from Harold Robbins's novel The Carpetbaggers portrayed by Alan Ladd two years earlier in a movie version of that novel. Nevada Smith was an enormously successful Western action adventure prequel that also featured Karl Malden and Suzanne Pleshette. After starring in 1965's The Cincinnati Kid as a poker player, McQueen earned his only Academy Award nomination in 1966 for his role as an engine-room sailor in The Sand Pebbles, in which he starred opposite Candice Bergen and Richard Attenborough, whom he had previously worked with in The Great Escape).[14]

He followed his Oscar nomination with 1968's Bullitt, one of his best-known films, and his personal favorite, which co-starred Jacqueline Bisset, Robert Vaughn and Don Gordon. It featured an unprecedented (and endlessly imitated) car chase through San Francisco. Although McQueen did do the driving that appeared in closeup, this was about 10% of what is seen in the film's car chase. The rest of the driving by McQueen's character was done by stunt drivers Bud Ekins and Loren Janes.[36] The antagonist's black Dodge Charger was driven by veteran stunt driver Bill Hickman; McQueen, his stunt drivers and Hickman spent several days before the scene was shot practicing high-speed, close-quarters driving.[37] Bullitt went so far over budget that Warner Brothers cancelled the contract on the rest of his films, seven in all.

When Bullitt became a huge box-office success, Warner Brothers tried to woo him back, but he refused, and his next film was made with an independent studio and released by United Artists. For this film, McQueen went for a change of image, playing a debonair role as a wealthy executive in The Thomas Crown Affair with Faye Dunaway in 1968. The following year, he made the southern period piece The Reivers.

The 1970s[]

In 1971, McQueen starred in the poorly received auto-racing drama Le Mans, followed by Junior Bonner in 1972, a story of an aging rodeo rider. He worked for director Sam Peckinpah again with the leading role in The Getaway, where he met future wife Ali MacGraw. He followed this with a physically demanding role as a Devil's Island prisoner in 1973's Papillon, featuring Dustin Hoffman as his character's tragic sidekick.

In 1973, The Rolling Stones referred to McQueen in the song "Star Star" from the album Goats Head Soup for which an amused McQueen reportedly gave personal permission.[38] The lines were "Star f***er, star f***er, star f***er, star f***er star / Yes you are, yes you are, yes you are / Yeah, Ali MacGraw got mad with you / For givin' head to Steve McQueen".

By the time of The Getaway, McQueen was the world's highest-paid actor,[39] but after 1974's The Towering Inferno, co-starring with his long-time professional rival Paul Newman and reuniting him with Dunaway, became a tremendous box-office success, McQueen all but disappeared from the public eye, to focus on motorcycle racing and traveling around the country in a motor home and on his vintage Indian motorcycles. He did not return to acting until 1978 with An Enemy of the People, playing against type as a bearded, bespectacled 19th-century doctor in this adaptation of a Henrik Ibsen play. The film was never properly released theatrically, but has appeared occasionally on PBS.

His last two films were loosely based on true stories: Tom Horn, a Western adventure about a former Army scout-turned professional gunman who worked for the big cattle ranchers hunting down rustlers, and later hanged for murder in the shooting death of a sheepherder, and The Hunter, an urban action movie about a modern-day bounty hunter, both released in 1980.

Missed roles[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2017) |

McQueen was offered the lead male role in Breakfast at Tiffany's, but was unable to accept due to his Wanted: Dead or Alive contract (the role went to George Peppard).[7][40] He turned down parts in Ocean's 11,[41] Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (his attorneys and agents could not agree with Paul Newman's attorneys and agents on top billing),[7][40] The Driver,[42][43] Apocalypse Now,[14]:172 California Split,[44] Dirty Harry, A Bridge Too Far, The French Connection (he did not want to do another cop film),[7][40] and Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

According to director John Frankenheimer and actor James Garner in bonus interviews for the DVD of the film Grand Prix, McQueen was Frankenheimer's first choice for the lead role of American Formula One race car driver Pete Aron. Frankenheimer was unable to meet with McQueen to offer him the role, so he sent Edward Lewis, his business partner and the producer of Grand Prix. McQueen and Lewis instantly clashed, the meeting was a disaster, and the role went to Garner.

Director Steven Spielberg said McQueen was his first choice for the character of Roy Neary in Close Encounters of the Third Kind. According to Spielberg, in a documentary on the Close Encounters DVD, Spielberg met him at a bar, where McQueen drank beer after beer. Before leaving, McQueen told Spielberg that he could not accept the role because he was unable to cry on cue.[45][46] Spielberg offered to take the crying scene out of the story, but McQueen demurred, saying that it was the best scene in the script. The role eventually went to Richard Dreyfuss.

William Friedkin wanted to cast McQueen as the lead in the action/thriller film Sorcerer (1977). Sorcerer was to be filmed primarily on location in the Dominican Republic, but McQueen did not want to be separated from Ali MacGraw for the duration of the shoot. McQueen then asked Friedkin to let MacGraw act as a producer, so she could be present during principal photography. Friedkin would not agree to this condition, and cast Roy Scheider instead of McQueen. Friedkin later remarked that not casting McQueen hurt the film's performance at the box office.

Spy novelist Jeremy Duns revealed that McQueen was considered for the lead role in a film adaptation of The Diamond Smugglers, written by James Bond creator Ian Fleming; McQueen would play John Blaize, a secret agent gone undercover to infiltrate a diamond-smuggling ring in South Africa. There were complications with the project which was eventually shelved, although a 1964 screenplay does exist.[47]

McQueen and Barbra Streisand were tentatively cast in The Gauntlet, but the two could not get along, and both withdrew from the project. The lead roles were filled by Clint Eastwood and Sondra Locke.

McQueen expressed interest in the Rambo character in First Blood when David Morrell's novel appeared in 1972, but the producers rejected him because of his age.[48][49] He was offered the title role in The Bodyguard (to star Diana Ross) when it was proposed in 1976, but the film did not reach production until years after McQueen's death (which eventually starred Kevin Costner and Whitney Houston in 1992).[50] Quigley Down Under was in development as early as 1974, with McQueen in consideration for the lead, but by the time production began in 1980, McQueen was ill and the project was scrapped until a decade later, when Tom Selleck starred.[51] McQueen was offered the lead in Raise the Titanic, but felt that the script was flat. He was under contract to Irwin Allen after appearing in The Towering Inferno and offered a part in a sequel in 1980, which he turned down. The film was scrapped and Newman was brought in by Allen to make When Time Ran Out, which was a box office bomb. McQueen died shortly after passing on The Towering Inferno 2.[citation needed]

Stunts, motor racing and flying[]

McQueen was an avid motorcycle and race car enthusiast. When he had the opportunity to drive in a movie, he performed many of his own stunts, including some of the car chases in Bullitt and the motorcycle chase in The Great Escape.[52] Although the jump over the fence in The Great Escape was done by Bud Ekins for insurance purposes, McQueen did have considerable screen time riding his 650 cc Triumph TR6 Trophy motorcycle. It was difficult to find riders as skilled as McQueen.[53] At one point, using editing, McQueen is seen in a German uniform chasing himself on another bike. Around half of the driving in Bullitt was performed by Loren Janes.[36]

McQueen and John Sturges planned to make Day of the Champion,[54] a movie about Formula One racing, but McQueen was busy with the delayed The Sand Pebbles. They had a contract with the German Nürburgring, and after John Frankenheimer shot scenes there for Grand Prix, the reels were turned over to Sturges. Frankenheimer was ahead in schedule, and the McQueen-Sturges project was called off.

McQueen considered being a professional race car driver. He had a one-off outing in the British Touring Car Championship in 1961, driving a BMC Mini at Brands Hatch, finishing third.[55] In the 1970 12 Hours of Sebring race, Peter Revson and McQueen (driving with a cast on his left foot from a motorcycle accident two weeks earlier) won with a Porsche 908/02 in the three-litre class and missed winning overall by 21.1 seconds to Mario Andretti/Ignazio Giunti/Nino Vaccarella in a five-litre Ferrari 512S.[56] This same Porsche 908 was entered by his production company Solar Productions as a camera car for Le Mans in the 1970 24 Hours of Le Mans later that year. McQueen wanted to drive a Porsche 917 with Jackie Stewart in that race,[57] but the film backers threatened to pull their support if he did. Faced with the choice of driving for 24 hours in the race or driving for the entire summer making the film, McQueen opted for the latter.[failed verification][58]

McQueen competed in off-road motorcycle racing, frequently running a BSA Hornet.[14] He was also set to co-drive in a Triumph 2500 PI for the British Leyland team in the 1970 London-Mexico rally, but had to turn it down due to movie commitments.[14] His first off-road motorcycle was a Triumph 500 cc, purchased from Ekins. McQueen raced in many top off-road races on the West Coast, including the Baja 1000, the Mint 400, and the Elsinore Grand Prix.

In 1964, McQueen and Ekins were part of a four-rider (plus one reserve) first-ever official US team-entry into the Silver Vase category of the International Six Days Trial,[59] an Enduro-type off-road motorcycling event held that year in Erfurt, East Germany.[60] The "A" team arrived in England in late August to collect their mix of 649 cc and 490 cc twins from the Triumph factory before modifying them for off-road use.[59] Initially let down with transport arrangements by a long-established English motorcycle dealer, Triumph dealer H&L Motors stepped-in to provide a suitable vehicle.[61] On arrival in Germany, the team, with their English temporary manager, were surprised to find a Vase "B" team, comprising expat Americans living in Europe, had entered themselves privately to ride European-sourced machinery.[62]

McQueen's ISDT competition number was 278, which was based on the trials starting order.[63] Both teams crashed repeatedly.[62][64] McQueen retired due to irreparable crash damage,[65] and Ekins withdrew with a broken leg, both on day three (Wednesday). Only one member of the "B" team finished the six-day event.[64] UK monthly magazine Motorcycle Sport commented: "Riding Triumph twins...[the team] rode everywhere with great dash, if not in admirable style, falling off frequently and obviously out for six days' sport without too many worries about who was going to win (they knew it would not be them)".[65]

He was inducted in the Off-road Motorsports Hall of Fame in 1978. In 1971, McQueen's Solar Productions funded the classic motorcycle documentary On Any Sunday, in which McQueen is featured, along with racing legends Mert Lawwill and Malcolm Smith. The same year, he also appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated magazine riding a Husqvarna dirt bike.

McQueen designed a motorsports bucket seat, for which a patent was issued in 1971.[58]:93[66]

In a segment filmed for The Ed Sullivan Show, McQueen drove Sullivan around a desert area in a dune buggy at high speed. Afterward, Sullivan said, "That was a 'helluva' ride!"

McQueen owned a number of classic motorcycles, as well as several exotics and vintage cars, including:

- Porsche 917, Porsche 908, and Ferrari 512 race cars from the Le Mans film

- Porsche 911S (used in the opening sequence of the Le Mans film)

- 1963 Ferrari 250 GT Berlinetta Lusso[67]

- 1967 Ferrari 275GTB/4[68]

- 1956 Jaguar XKSS (right-hand drive) (now on exhibit at the Petersen Automotive Museum in Los Angeles, California)

- 1958 Porsche 356 Speedster 1600 Super (black exterior, interior and top) (McQueen drove the car in numerous SCCA racing events)[69][70]

- 1968 Ford GT40 (Gulf liveried) (used in the Le Mans film)[71]

- 1953 Siata 208s (McQueen replaced the Siata badges with Ferrari badges and called it his "little Ferrari")[72]

- 1967 Mini Cooper-S (McQueen had the car customized by Lee Brown with changes including a single foglight, a wood dash, a recessed antenna and a custom brown paint job)[73]

- 1951 Chevrolet Styline De Lux Convertible (used in The Hunter, McQueen bought the car in 1979 after filming ended)[74]

- 1952 Chevrolet 3800 pickup camper conversion (McQueen used the truck for cross-country camping trips. It was the last car he rode in before his death)[75]

- 1950 Hudson Commodore convertible

- 1952 Hudson Wasp 2-door sedan[76]

- 1953 Hudson Hornet 4-door Sedan[77]

- 1956 GMC Suburban

- 1958 GMC Pickup Truck (Reportedly one of McQueen's favorite cars, it is powered by a 336 Ci V8 which has been modified. The tag "MQ3188" is a reference to the ID number assigned to him when he was in reform school)[78]

- 1931 Lincoln Club Sedan

- 1935 Chrysler Airflow Imperial Sedan[79]

- 1969 Chevrolet Baja Hickey race truck (originally debuted at the 1968 Mexican 1000 Rally and was driven by Cliff Coleman, Johnny Diaz, Mickey Thompson and others during its racing career; said to be the first truck specifically constructed by GM for use in the Mexican 1000; McQueen bought it from General Motors in 1970)[80]

In spite of numerous attempts, McQueen was never able to purchase the Ford Mustang GT 390 he drove in Bullitt, which featured a modified drivetrain that suited McQueen's driving style. One of the two Mustangs used in the film was badly damaged, judged beyond repair, and believed to have been scrapped until it surfaced in Mexico in 2017,[81] while the other one, which McQueen attempted to purchase in 1977,[82] is hidden from the public eye. At the 2018 North American International Auto Show the GT 390 was displayed, in its current non-restored condition, with the 2019 Ford Mustang "Bullitt".[83]

McQueen also flew and owned, among other aircraft, a 1945 Stearman, tail number N3188, (his student number in reform school), a 1946 Piper J-3 Cub, and an award-winning 1931 Pitcairn PA-8 bip, flown in the US Mail Service by famed World War I flying ace Eddie Rickenbacker. They were hangared at Santa Paula Airport an hour northwest of Hollywood, where he lived his final days.[14]

Personal life[]

Relationships and friendships[]

While still attending Stella Adler's school in New York, McQueen dated Gia Scala.[28]

On November 2, 1956, he married Filipino actress and dancer Neile Adams,[84] with whom he had a daughter, Terry Leslie (June 5, 1959 – March 19, 1998[85][86]) and a son, Chad (born December 28, 1960).[87] McQueen and Adams divorced in 1972.[85] In her autobiography, My Husband, My Friend, Adams stated that she had an abortion in 1971, when their marriage was on the rocks.[32] One of McQueen's four grandchildren is actor Steven R. McQueen (who is best known for playing Jeremy Gilbert in The Vampire Diaries and Jimmy Borelli in Chicago Fire).[88]

Mamie Van Doren claimed to have had an affair with McQueen and tried hallucinogens with him around 1959.[89] Actress-model Lauren Hutton also said that she had an affair with McQueen in the early 1960s.[90][91] In 1971–1972, while separated from Adams, McQueen had a relationship with Junior Bonner co-star Barbara Leigh,[85][92] which included her pregnancy and an abortion.[93]

On August 31, 1973, McQueen married actress Ali MacGraw, his co-star in The Getaway, but this marriage ended in a divorce in 1978.[94] MacGraw suffered a miscarriage during their marriage.[95] Some friends later claimed that MacGraw was the one true love of McQueen's life: "He was madly in love with her until the day he died."

On January 16, 1980, less than a year before his death, McQueen married model Barbara Minty.[96] Barbara Minty, in her book Steve McQueen: The Last Mile, wrote of McQueen becoming an Evangelical Christian toward the end of his life.[97] This was due in part to the influences of his flying instructor, Sammy Mason, Mason's son Pete, and Barbara herself.[98] McQueen attended his local church, Ventura Missionary Church, and was visited by evangelist Billy Graham shortly before his death.[98][99]

In 1973 McQueen was one of the pallbearers at the funeral of Bruce Lee along with James Coburn, Bruce's brother Robert Lee, Peter Chin, Dan Inosanto, and Taky Kimura.[100]

After discovering a mutual interest in racing, McQueen and Great Escape co-star James Garner became good friends and lived near each other. McQueen recalled:

I could see that Jim was neat around his place. Flowers trimmed, no papers in the yard... grass always cut. So to piss him off, I'd start lobbing empty beer cans down the hill into his driveway. He'd have his drive all spic 'n' span when he left the house, then get home to find all these empty cans. Took him a long time to figure out it was me.[14]

Lifestyle[]

McQueen followed a daily two-hour exercise regimen, involving weightlifting and, at one point, running 5 miles (8 km), seven days a week.[101] McQueen learned the martial art Tang Soo Do from ninth-degree black belt Pat E. Johnson.[7]

According to photographer William Claxton, McQueen smoked marijuana almost every day; biographer Marc Eliot stated that McQueen used a large amount of cocaine in the early 1970s. He was also a heavy cigarette smoker. McQueen sometimes drank to excess; he was arrested for driving while intoxicated in Anchorage, Alaska, in 1972.[102]

Manson connection[]

Two months after Charles Manson incited the murder of five people, including McQueen's friends Sharon Tate and Jay Sebring, the media reported police had found a hit list with McQueen's name on it. According to his first wife, McQueen began carrying a handgun at all times in public, including at Sebring's funeral.[103]

Charitable causes[]

McQueen had an unusual reputation for demanding free items in bulk from studios when agreeing to do a film, such as electric razors, jeans, and other items. It was later discovered McQueen donated these things to the Boys Republic reformatory school,[104] where he had spent time in his teen years. McQueen made occasional visits to the school to spend time with the students, often to play pool and speak about his experiences.[citation needed]

Illness and death[]

McQueen developed a persistent cough in 1978. He gave up cigarettes and underwent antibiotic treatments without improvement. His shortness of breath grew more pronounced, and on December 22, 1979, after filming The Hunter, a biopsy revealed pleural mesothelioma,[105] a cancer associated with asbestos exposure for which there is no known cure.

A few months later, McQueen gave a medical interview in which he blamed his condition on asbestos exposure.[106] McQueen believed that asbestos used in movie sound stage insulation and race-drivers' protective suits and helmets could have been involved, but he thought it more likely that his illness was a direct result of massive exposure while removing asbestos lagging (insulation) from pipes aboard a troop ship while he was in the Marines.[107][108]

By February 1980, evidence of widespread metastasis was found. He tried to keep the condition a secret, but on March 11, 1980, the National Enquirer disclosed that he had "terminal cancer".[109][110] In July 1980, McQueen traveled to Rosarito Beach, Mexico, for unconventional treatment after U.S. doctors told him they could do nothing to prolong his life.[111] Controversy arose over the trip because McQueen sought treatment from William Donald Kelley, who was promoting a variation of the Gerson therapy that used coffee enemas, frequent washing with shampoos, daily injections of fluid containing live cells from cattle and sheep, massages, and laetrile, a reputed anti-cancer drug available in Mexico, but long known to be both toxic and ineffective at treating cancer.[112][113][114] McQueen paid for Kelley's treatments by himself in cash payments which were said to have been upwards of $40,000 per month ($126,000 today) during his three-month stay in Mexico. Kelley's only medical license (until revoked in 1976) had been for orthodontics.[115] Kelley's methods caused a sensation in the traditional and tabloid press when it became known that McQueen was a patient.[116][117]

McQueen returned to the U.S. in early October. Despite metastasis of the cancer throughout McQueen's body, Kelley publicly announced that McQueen would be completely cured and return to normal life. McQueen's condition soon worsened and huge tumors developed in his abdomen.[115]

In late October 1980, McQueen flew to Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, Mexico, to have an abdominal tumor on his liver (weighing around five pounds (2.3 kg)) removed, despite warnings from his U.S. doctors that the tumor was inoperable and his heart could not withstand the surgery.[14]:212–13[115] Using the name "Samuel Sheppard", McQueen checked into a small Juárez clinic where the doctors and staff were unaware of his actual identity.[118]

On November 7, 1980, McQueen died of a heart attack at 3:45 a.m. at a Juárez hospital, 12 hours after surgery to remove or reduce numerous metastatic tumors in his neck and abdomen.[14] He was 50 years old.[119] According to the El Paso Times, McQueen died in his sleep.[120]

Leonard DeWitt of the Ventura Missionary Church presided over McQueen's memorial service.[97][98] McQueen was cremated and his ashes were spread in the Pacific Ocean.

Legacy[]

In 2007, Forbes said McQueen remained a popular star and still the "king of cool", even 27 years after his death, and was one of the highest-earning dead celebrities. A rights-management agency head credited Branded Entertainment Network (called Corbis at the time) with maximizing the profitability of his estate by limiting the licensing of McQueen's image, avoiding the commercial saturation of other dead celebrities' estates. As of 2007, McQueen's estate entered the top 10 of highest-earning dead celebrities.[121]

McQueen was inducted into the Hall of Great Western Performers in April 2007 in a ceremony at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.[122]

In November 1999, McQueen was inducted into the Motorcycle Hall of Fame. He was credited with contributions including financing the film On Any Sunday, supporting a team of off-road riders, and enhancing the public image of motorcycling overall.[123]

A film based on unfinished storyboards and notes developed by McQueen before his death was slated for production by McG's production company Wonderland Sound and Vision. Yucatán is described as an "epic adventure heist" film, scheduled for release in 2013 but still unreleased in February 2016.[124] Team Downey, the production company of Robert Downey, Jr. and his wife Susan Downey, expressed an interest in developing Yucatán for the screen.[125]

The Beech Grove, Indiana, Public Library formally dedicated the Steve McQueen Birthplace Collection on March 16, 2010, to commemorate the 80th anniversary of McQueen's birth on March 24, 1930.[126]

In 2012, McQueen was posthumously honored with the Warren Zevon Tribute Award by the Asbestos Disease Awareness Organization (ADAO).

Steve McQueen: The Man & Le Mans, a 2015 documentary, examines the actor's quest to create and star in the 1971 auto-racing film Le Mans. His son Chad McQueen and former wife Neile Adams are among those interviewed.

On September 28, 2017, there was a selected showing in some theaters of his life story and spiritual quest, Steve McQueen – American Icon.[127] There was an encore presentation on October 10, 2017.[128] The film received mostly positive reviews.[129] Kenneth R. Morefield of Christianity Today said it "offers a timeless reminder that even those among us living the most celebrated lives often long for the peace and sense of purpose that only God can provide".[130] Michael Foust of Wordslingers called it "one of the most powerful and inspiring documentaries I've ever seen."[131]

In the 2019 Quentin Tarantino film Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, McQueen is portrayed by Damian Lewis.

Archive[]

The Academy Film Archive houses the Steve McQueen-Neile Adams Collection, which consists of personal prints and home movies.[132] The archive has preserved several of McQueen's home movies.[133]

Ford commercials[]

In 1998, director Paul Street created a commercial for the Ford Puma. Footage was shot in modern-day San Francisco, set to the theme music from Bullitt. Archive footage of McQueen was used to digitally superimpose him driving and exiting the car in settings reminiscent of the film. The Puma shares the same number plate of the classic fastback Mustang used in Bullitt, and as he parks in the garage (next to the Mustang), he pauses and looks meaningfully at a motorcycle tucked in the corner, similar to that used in The Great Escape.[134]

In 2005, Ford used his likeness again, in a commercial for the 2005 Mustang. In the commercial, a farmer builds a winding racetrack, which he circles in the 2005 Mustang. Out of the cornfield comes McQueen. The farmer tosses his keys to McQueen, who drives off in the new Mustang. McQueen's likeness was created using a body double (Dan Holsten) and digital editing. Ford secured the rights to McQueen's likeness from the actor's estate licensing agent for an undisclosed sum.[citation needed]

At the Detroit Auto Show in January 2018, Ford unveiled the new 2019 Mustang Bullitt. The company called on McQueen's granddaughter, actress Molly McQueen, to make the announcement. After a brief rundown of the tribute car's particulars, a short film was shown in which Molly was introduced to the actual Bullitt Mustang, a 1968 Mustang Fastback with a 390 cubic-inch engine and a four-speed manual gearbox. That car has been in possession of the same family since 1974 and hidden away from the public until now, when it was driven out from under the press stand and up the center aisle of Ford's booth to much fanfare.[135]

Memorabilia[]

The blue-tinted sunglasses (Persol 714) worn by McQueen in the 1968 movie The Thomas Crown Affair sold at a Bonhams & Butterfields auction in Los Angeles for $70,200 in 2006.[136] One of his motorcycles, a 1937 Crocker, sold for a world-record price of $276,500 at the same auction. McQueen's 1963 metallic-brown Ferrari 250 GT Lusso Berlinetta sold for US$2.31 million at auction on August 16, 2007.[67] Except for three motorcycles sold with other memorabilia in 2006,[137] most of McQueen's collection of 130 motorcycles was sold four years after his death.[138][139] The 1970 Porsche 911S purchased while making the film Le Mans and appearing in the opening sequence was sold at auction in August 2011 for $1.375 million. From 1995 to 2011, McQueen's red 1957 fuel-injected Chevrolet convertible was displayed at the Petersen Automotive Museum in Los Angeles in a special Cars of Steve McQueen exhibit. It is now in the collection of actress Ruth Buzzi and her husband Kent Perkins. McQueen's British racing green 1956 Jaguar XKSS is also located in the Petersen Automotive Museum and is in drivable condition, having been driven by Jay Leno in an episode of Jay Leno's Garage. In August 2019, Mecum Auctions announced it would auction the Bullitt Mustang Hero Car at its Kissimmee auction, held January 2–12, 2020.[140] The car sold without reserve for $3.4 million ($3.74 million after commissions and fees).

Watch collection[]

The Rolex Explorer II, Reference 1655, known as Rolex Steve McQueen in the horology collectors' world, the Rolex Submariner, Reference 5512, which McQueen was often photographed wearing in private moments, sold for $234,000 at auction on June 11, 2009, a world-record price for the type.[141] McQueen was left-handed and wore the watch on his right wrist.[142][143]

McQueen was a sponsored ambassador for Heuer watches. In the 1970 film Le Mans, he famously wore a blue-faced Monaco Ref. 1133, which led to its cult status among watch collectors, purchasing six watches of the same model for the shoot of the film. On December 12, 2020, one of the last six models sold and one of two held in private hands was sold for a record US$2.208 million at a Phillips auction in New York, becoming the most expensive Heuer watch sold at auction.[144] Tag Heuer continues to promote its Monaco range with McQueen's image.[145]

In June 2018, Phillips announced McQueen's Rolex Submariner[146][147] to hit the auction block in September that year. However, there was controversy whether or not the watch was his personal watch worn by McQueen himself or if the watch was bought, engraved, then gifted.[148] Phillips later removed the watch from the auction block.

Filmography[]

Awards and honors[]

- Academy Awards

- (1967) Nominated – Best Actor in a Leading Role in The Sand Pebbles

- (1964) Nominated – Best Actor – Motion Picture Drama in Love with the Proper Stranger

- (1967) Nominated – Best Actor – Motion Picture Drama in The Sand Pebbles

- (1970) Nominated – Best Actor – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy in The Reivers

- (1974) Nominated – Best Actor – Motion Picture Drama in Papillon

- (1963) – Won – Best Actor in The Great Escape[149]

References[]

- ^ Aaker, Everett (2017). Television Western Players, 1960–1975: A Biographical Dictionary. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-6250-3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Laurie, Greg (2019). Steve McQueen: The Salvation of an American Icon. Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-35620-2.

- ^ "Terry Leslie McQueen dies at 38". Variety. March 23, 1998. Archived from the original on January 27, 2018. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- ^ Arnold, Gary (November 8, 1980). "Movie Hero Steve McQueen Dies of Heart Attack at Age of 50". Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 9, 2018. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- ^ Lehman, Craig (January 27, 2015). "Steve McQueen becomes highest paid actor in the world". Buffalo Reflex. Archived from the original on March 22, 2019. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Indiana State Board of Health Certificate of Birth". cineartistes.com. Archived from the original on September 5, 2017. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Terrill, Marshall (1993). Steve McQueen: Portrait of an American Rebel. Plexus Press. ISBN 978-1-556-11380-2.

- ^ "Obituary". Variety. November 12, 1980.

- ^ Mackay, Kathy (October 20, 1980). "Steve McQueen, Stricken with Cancer, Seeks a Cure at a Controversial Mexican Clinic". People. Archived from the original on April 30, 2010. Retrieved August 7, 2010.

Raised as a Catholic, he now feels he has, according to one friend, 'made his peace with God.'

- ^ Leith, William (November 26, 2001). "Easy rider". New Statesman. Archived from the original on June 8, 2011. Retrieved August 7, 2010.

Steve knew what it was like to be dyslexic, deaf, illegitimate, backward, beaten, abused, deserted and raised Catholic in a Protestant heartland.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Spiegel, Penina (1987). McQueen: The Untold Story of a Bad Boy in Hollywood. Berkley Books. ISBN 978-0-425-10486-6. Retrieved January 15, 2012 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Terrill, Marshall (2020). Steve McQueen: In His Own Words. Deerfield, IL: Dalton Watson. p. 158. ISBN 978-1-85443-271-1. Archived from the original on April 16, 2021. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Eliot, Marc (2011). Steve McQueen: A Biography. Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-45323-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j Nolan, William (1984). McQueen. Congdon & Weed Inc. ISBN 978-0-312-92526-0.

- ^ McQueen Toffel, Neile (1986). My Husband, My Friend. Penguin Group. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-451-14735-6.

- ^ Terrill, Marshall (2020). Steve McQueen: In His Own Words. Deerfield, IL: Dalton Watson. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-85443-271-1. Archived from the original on April 16, 2021. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ Steve McQueen. Archived from the original on April 16, 2021. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ McCoy, Malachy (1975). Steve McQueen, The Unauthorized Biography. Signet Books. ISBN 978-0-352-39811-6.

- ^ Gehring, Wes D. (April 20, 2013). Steve McQueen: The Great Escape. Indiana Historical Society. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-0-87195-309-4.

- ^ Terrill, Marshall (2020). Steve McQueen: In His Own Words. Deerfield, IL: Dalton Watson. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-85443-271-1. Archived from the original on April 16, 2021. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fried, Ellen (Spring 2006), "VIPs in Uniform; A look at the military files of the famous and the famous-to-be", Prologue: The Journal of the National Archives, National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration, 38 (1), archived from the original on April 24, 2021, retrieved January 10, 2020

- ^ Jump up to: a b Zimmerman, Dwight Jon (2017), The Life Steve McQueen, Motorbooks, p. 17, ISBN 978-0-7603-5811-5, archived from the original on August 19, 2020, retrieved January 10, 2020

- ^ Enk, Bryan (July 26, 2013). "Real Life Tough Guys". Yahoo.com. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ^ Gehring, Wes D. (April 20, 2013). Steve McQueen:The Great Escape. Indiana Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-87195-333-9. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved January 10, 2020.

- ^ Terrill, Marshall (2020). Steve McQueen: In His Own Words. Deerfield, IL: Dalton Watson. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-85443-271-1. Archived from the original on April 16, 2021. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ "HB Studio – Notable Alumni". HB Studio. Archived from the original on December 2, 2017. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ^ Karlen, Neal, "The Story of Yiddish: How a Mish-Mosh of Languages Saved the Jews," William Morrow, 2008, ISBN 0-06-083711-X

- ^ Jump up to: a b Saint James, Sterling (December 10, 2014). Gia Scala: The First Gia. Parhelion House. ISBN 978-0-9893695-1-0.

- ^ "CPI Inflation Calculator". U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. August 17, 2011. Archived from the original on February 12, 2013. Retrieved January 15, 2012.

- ^ Jukebox Jury: Research Video: Music Footing Licensing Agency and Vintage Television Footage Archive

- ^ "Our Lady of Loretto Elementary School: Local History Timeline". OLL Alumni. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved June 23, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b McQueen Toffel, Neile (2006). My Husband, My Friend. Signet Books. ISBN 978-1-4259-1818-7.

- ^ Wallach, Eli (2005). The Good, the Bad and Me: my anecdotage. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-15-101189-6.

- ^ Rubin, Steve. – Documentary: Return to 'The Great Escape. – MGM Home Entertainment. – 1993.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard (1999). Leonard Maltin's Family Film Guide. New York: Signet. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-451-19714-6.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Myers, Marc (January 26, 2011). "Chasing the Ghosts of 'Bullitt'". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on August 21, 2017. Retrieved January 26, 2011.

- ^ Renfroe, Jeff (2014), "I Am Steve McQueen", Documentary DVD, Network Entertainment

- ^ Carr, Tony (1976). The Rolling Stones: an illustrated record. Harmony Books. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-517-52641-5.

- ^ Barger, Ralph; Zimmerman, Keith; Zimmerman, Kent (2003). Ridin' High, Livin' Free: Hell-Raising Motorcycle Stories. Harper Paperbacks. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-06-000603-7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Jones Meg. – "McQueen biography is portrait of a rebel". – Milwaukee Sentinel. – March 19, 1994.

- ^ Rahner, Mark (June 12, 2005). "New DVD collections remind us why McQueen was the King of Cool". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ^ Burger, Mark. – "Walter Hill Crime Story from 1978 Led the Way in its Genre". – Winston-Salem Journal. – June 9, 2005.

- ^ French, Philip. – Review: "DVD club: No 44 The Driver". – The Observer – November 5, 2006.

- ^ Shields, Mel. – "Elliott Gould has had quite a career to joke about". – The Sacramento Bee. – October 27, 2002.

- ^ , Clarke, Roger. – "The Independent: Close Encounters of the Third Kind 9 pm Film4". – The Independent. – April 21, 2007.

- ^ Tucker, Reed, Isaac Guzman, and John Anderson. – "Cinema Paradiso: The True Story of an Incredible Year in Film". – New York Post. – August 5, 2007.

- ^ "From Johannesburg With Love", in The Sunday Times, March 7, 2010.

- ^ Toppman, Lawrence. – "Will He or Won't He?". – The Charlotte Observer. – May 22, 1988.

- ^ Morrell, David, Jay MacDonald. – "Writers find fame with franchises". The News-Press. – March 2, 2003.

- ^ Beck, Marilyn, Stacy Jenel Smith. – "Costner Sings to Houston's Debut". – Los Angeles Daily News. – October 7, 1991.

- ^ Persico Newhouse, Joyce J. – "'Perfect Hero' Selleck Takes Aim at Action". – Times Union. – October 18, 1990.

- ^ Terrill, Marshall (2020). Steve McQueen: In His Own Words. Deerfield, IL: Dalton Watson. p. 151. ISBN 978-1-85443-271-1. Archived from the original on April 16, 2021. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ According to the commentary track on The Great Escape DVD.

- ^ McQueen Toffel, Neile, (1986). – Excerpt: My Husband, My Friend Archived May 15, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. – (c/o The Sand Pebbles). – New York, New York: Atheneum. – ISBN 0-689-11637-3

- ^ "From Didcot to McQueen and Mulholland Drive – Sir John Whitmore". Race Driver Blog. September 22, 2013. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- ^ "1970 SEBRING 12 HOURS". Motorsport Magazine. March 21, 1970. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- ^ "Did he lose the plot?". Motorsport Magazine. Archived from the original on August 11, 2020. Retrieved August 1, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stone, Matthew L, (2007). – Excerpt: "Steve McQueen's Automotive Legacy Archived April 19, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. – Mcqueen's Machines: The Cars And Bikes Of A Hollywood Icon. – (c/o Mustang & Fords). – St. Paul, Minnesota: Motorbooks. – ISBN 0-7603-2866-8

- ^ Jump up to: a b Motor Cycle, August 27, 1964. p.451. On the Rough by Peter Fraser. "All of them have been riding regularly in US Enduros and scrambles, but Bud is the only one with previous ISDT experience. He won golds last year and in 1962". Accessed December 7, 2015

- ^ "ISDT Sort-out". Motor Cycle. 113 (3196): 538.

- ^ Motor Cycle, September 3, 1964. pp.492–494. ISDT Opening by Peter Fraser. Accessed December 7, 2015

- ^ Jump up to: a b Motor Cycle, September 10, 1964. pp.508–510. ISDT First report by Peter Fraser. Accessed December 7, 2015

- ^ Stone, Matt (November 7, 2010). McQueen's Machines: The Cars and Bikes of a Hollywood Icon. MBI Publishing Company. pp. 154–158. ISBN 978-1-61060-111-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Motor Cycle, September 24, 1964. pp.578-580. ISDT Round up by Peter Fraser. Accessed December 7, 2015

- ^ Jump up to: a b Motorcycle Sport, November 1964, pp.411–418 "Steve McQueen, last man on the course after a long stop to repair a broken chain, was speeding along to catch up when he collided with a motorcyclist; the Triumph was sadly mangled, the front fork doubled under the frame". Accessed December 7, 2015.

- ^ U.S. Patent D219813

- ^ Jump up to: a b Valetkevitch, Caroline (April 28, 2007). "Steve McQueen's Ferrari up for auction". Thomson Reuters. Archived from the original on February 24, 2008. Retrieved May 26, 2008.

- ^ "Steve McQueen's greatest cars | Gentleman's Journal". The Gentleman's Journal. July 16, 2015. Archived from the original on March 30, 2018. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

- ^ Shahrabani, Benjamin (May 8, 2014). "Book Review: McQueen's Machines". Petrolicious. Archived from the original on March 30, 2018. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

- ^ "Steve McQueen and his Speedster – Speedsters – a site dedicated to all aspects of Porsche Speedsters from the 1950s to the present day". speedsters.com. Archived from the original on April 26, 2018. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- ^ Preston, Benjamin. "Steve McQueen's $11 Million GT40 Is The Most Expensive American Car Ever Sold". Jalopnik. Archived from the original on April 26, 2018. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- ^ Hyde, Justin. "The car that made Steve McQueen a Ferrari poser". Jalopnik. Archived from the original on March 30, 2018. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

- ^ "Steve McQueen's Mark II1967 Cooper S | Schomp MINI". Schomp MINI. April 4, 2016. Archived from the original on March 30, 2018. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- ^ "Stars & Their Cars: Steve McQueen Edition – Historic Vehicle Association (HVA)". Historic Vehicle Association (HVA). September 9, 2014. Archived from the original on April 26, 2018. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- ^ "1952 Chevrolet Steve MCQUEEN Custom Camper Pickup | F312 | Santa Monica 2013 | Mecum Auctions". Mecum Auctions. Archived from the original on April 26, 2018. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- ^ "Hudson Wasp". mcqueenonline.com. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017. Retrieved June 5, 2018.

- ^ "RM Sotheby's – r145 1953 Hudson Hornet Sedan". RM Sotheby's. July 21, 2017. Archived from the original on April 26, 2018. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- ^ "Buy Steve McQueen's '58 GMC truck". Autoblog. Archived from the original on December 5, 2018. Retrieved June 5, 2018.

- ^ "Steve McQueen's old camper for sale". topgear.com. July 18, 2013. Archived from the original on April 26, 2018. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- ^ "Steve McQueen Owned Baja Race Truck Sells For $60,000, Other McQueen Vehicles Fail To Sell At Auction/". hemmings.com. Archived from the original on April 26, 2018. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- ^ "Steve McQueen's "Bullitt" Mustang found in Mexico junkyard". CBSNews.com. Archived from the original on December 16, 2017. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on May 14, 2013. Retrieved August 5, 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Lee, Kristen. "We Got Up Close And Personal With The Original Bullitt Mustang". Jalopnik.com. Archived from the original on January 24, 2018. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- ^ "Steve McQueen: King of Cool". Life. June 1, 1963. Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved September 11, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Biography for Steve McQueen". Turner Classic Movies. 2009. Archived from the original on August 7, 2010. Retrieved September 11, 2009.

- ^ "Terry McQueen; Daughter of Actor Owned Production Company". Los Angeles Times. March 21, 1998. Archived from the original on April 5, 2016. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- ^ Terrill, Marsall (2020). Steve McQueen: In His Own Words. Deerfield, IL: Dalton Watson. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-85443-271-1. Archived from the original on April 16, 2021. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ Malcolm Boyes (October 17, 1983). "Steve McQueen's Actor Son, Chad, Is Following in His Dad's Tire Tracks as Well". People. Archived from the original on December 5, 2009. Retrieved September 11, 2009.

- ^ "Mamie Van Doren Bares All". Star-News. August 5, 1987. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ "McQueen Tops Lauren.s Sex List". Contactmusic.com. March 27, 2003. Archived from the original on March 29, 2014. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- ^ "After brush with death, Lauren Hutton's life wish pulls her through – GOMC – Celebs". Girlonamotorcycle.la. Archived from the original on January 21, 2014. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- ^ "BarbaraLeigh.com". BarbaraLeigh.com. Archived from the original on December 23, 2011. Retrieved January 15, 2012.

- ^ "Barbara Leigh Interview". McQueenonline.com. Archived from the original on March 2, 2012. Retrieved January 15, 2012.

- ^ Rachel Sexton (2009). "Steve McQueen – Career Retrospective". moviefreak.com. Archived from the original on 6 May 2009. Retrieved 11 September 2009.

- ^ MacGraw, Ali (1991). Moving Pictures. New York: Bantam Books.

- ^ All Movie Guide (2009). "title". American Movie Classics Company LLC. Archived from the original on 25 November 2009. Retrieved 11 September 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b McQueen, Barbara (2007). – Steve McQueen: The Last Mile. – Deerfield, Illinois: Dalton Watson Fine Books. – ISBN 978-1-85443-227-8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Johnson, Brett. – "Big legend in a small town – Action film hero lived quiet life in Santa Paula before 1980 death." – Ventura County Star. – January 13, 2008.

- ^ DVD Video: Steve McQueen, The Essence of Cool.

- ^ Burrows, Alyssa (October 21, 2002). "Lee, Bruce (1940–1973), Martial Arts Master and Film Maker". History Link.org. Retrieved April 15, 2017.

- ^ Terrill, Marshall (2020). Steve McQueen: In His Own Words. Deerfield, IL: Dalton Watson. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-85443-271-1. Archived from the original on April 16, 2021. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ "Movie star's antics failed to impress Anchorage policeman". The Bulletin. Bend, Oregon. June 29, 1972. p. 8.

- ^ Dunne, Dominick. The Way We Lived Then: Recollections of a Well Known Name Dropper. 1999. New York, New York: Crown Publishers. ISBN 0-609-60388-4.

- ^ John Dominis/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images. "Steve McQueen Returns to Reform School" 1963, accessed February 7, 2011

- ^ Lerner, BH (2006). When Illness Goes Public. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 141ff. ISBN 978-0-8018-8462-7.

- ^ McQueen, Steve (1980). "Medical interview" (Interview). Interviewed by Burgh Joy, clinical professor at UCLA. Personal archives of Barbara McQueen.

- ^ Spiegel, Penina (1986). McQueen: The Untold Story of a Bad Boy in Hollywood. New York: Doubleday and Co. ISBN 978-0-385-19392-4.

- ^ Sandford, Christopher (2003), McQueen: The Biography, New York: Taylor Trade Publishing, pp. 42, 126, 213, 324, 391, 410

- ^ Jackson, Kathy Merlock; Payne, Lisa Lyon; Stolley, Kathy Shepherd (December 24, 2015). The Intersection of Star Culture in America and International Medical Tourism: Celebrity Treatment. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-8688-6. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Roberts, Paul G. (October 2, 2014). Style Icons Vol 1 Golden Boys. Fashion Industry Broadcast. ISBN 978-1-62776-032-4. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Lerner, Barron H. (November 15, 2005). "McQueen's Legacy of Laetrile". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 11, 2010. Retrieved May 24, 2010.

- ^ Herbert, V (May 1979). "Laetrile: the cult of cyanide. Promoting poison for profit". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 32 (5): 1121–58. doi:10.1093/ajcn/32.5.1121. PMID 219680.

- ^ Lerner IJ (February 1984). "The whys of cancer quackery". Cancer. 53 (3 Suppl): 815–9. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19840201)53:3+<815::AID-CNCR2820531334>3.0.CO;2-U. PMID 6362828.

- ^ Nightingale, SL (1984). "Laetrile: the regulatory challenge of an unproven remedy". Public Health Rep. 99 (4): 333–8. PMC 1424606. PMID 6431478.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Worthington, Roger. "A Candid Interview with Barbara McQueen 26 Years After Mesothelioma Claimed the Life of Husband and Hollywood Icon, Steve McQueen". The Law Office of Roger G. Worthington P.C. October 27, 2006.

- ^ European Stars and Stripes, November 9, 1980, p. 2.

- ^ Elyria (November 8, 1980), Ohio Chronicle Telegram, p. C-5.

- ^ Marcelo, Abeal (April 10, 2015). Steve McQueen: The race of his life. Editorial Dunken. ISBN 978-987-02-8078-1. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Flint, Peter (November 8, 1980). "Steve McQueen, 50, Is Dead of a Heart Attack After Surgery for Cancer; Family Was at Bedside Established His Stardom In 'Bullitt' and 'Papillon' Friend Suggested Acting 'Don't Cap Me Up'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 22, 2018. Retrieved May 26, 2008.

- ^ Long, Trish (April 25, 2015). "Steve McQueen's last hours in Juarez". El Paso Times. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ^ "Top-Earning Dead Celebrities". Forbes. October 29, 2007. Archived from the original on October 27, 2020. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ^ "Steve McQueen honored at Western awards". USA Today. April 23, 2007. Archived from the original on March 8, 2014. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- ^ Steve McQueen – Motorcycle Hall of Fame. Motorcycle Hall of Fame Museum. 2009. Archived from the original on February 16, 2009.

- ^ Cullum, Paul (May 14, 2006). "Steve McQueen's Dream Movie Wakes Up With a Vrooom!". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 7, 2008. Retrieved May 26, 2008.

- ^ "Downey Jr. Launches Production Company; Lines Up Steve McQueen's 'Yucatan'". The Film Stage. June 14, 2010. Archived from the original on August 31, 2011. Retrieved June 14, 2010.

- ^ "Steve McQueen Birthplace Collection". Beech Grove Public Library. Archived from the original on June 22, 2010. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ^ "Steve McQueen: American Icon – Coming Soon To Digital HD". Steve McQueen: American Icon. Archived from the original on January 26, 2018. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- ^ "Encore showings for "Steve McQueen: American Icon"". wbfj.fm. October 9, 2017. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- ^ Steve McQueen: American Icon, archived from the original on November 30, 2017, retrieved April 1, 2018

- ^ "The King of Cool's Conversion Story". christianitytoday.com. Archived from the original on November 26, 2017. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ^ "REVIEW: Steve McQueen's faith explored in powerful new documentary". WordSlingers. September 15, 2017. Archived from the original on August 12, 2018. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ^ "Steve McQueen-Neile Adams Collection". Academy Film Archive. October 14, 2015. Archived from the original on July 3, 2016. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

- ^ "Preserved Projects". Academy Film Archive. Archived from the original on October 20, 2020. Retrieved September 18, 2020.

- ^ "Ford Puma 'Steve McQueen' Directed by Paul Street". YouTube. Archived from the original on October 24, 2018. Retrieved July 27, 2017.

- ^ "2019 Ford Mustang Bullitt rocks Detroit with Molly McQueen". cnet.com. January 14, 2018. Archived from the original on February 23, 2018. Retrieved February 23, 2018.

- ^ "McQueen's shades sell for £36,000". BBC News. November 12, 2006. Archived from the original on April 25, 2010. Retrieved May 24, 2010.

- ^ Sale 14037 – The Steve McQueen Sale and Collectors' Motorcycles & Memorabilia; The Petersen Automotive Museum, Los Angeles, California, 11 Nov 2006. Bonhams & Butterfields Auctioneers. Archived from the original on June 26, 2009.

- ^ Macy, Robert (November 24, 1984). "Steve McQueen's possessions to be auctioned today". The Evening Independent. St Petersburg, Florida. Associated Press.

- ^ Edwards, David. "The Steve McQueen Auction". Cycle World. Archived from the original on August 22, 2007.

- ^ "Mecum Unveils Bullitt Mustang Hero Car to be Auctioned at Kissimmee 2020 | News". mecum.com. Archived from the original on August 15, 2019. Retrieved August 15, 2019.

- ^ NationalJewelerNetwork.com Archived January 16, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Famous Left-Handers – he signed into what's my line with his right hand and his gun is on his right hip – not sure he is left handed". Indiana.edu. Archived from the original on February 8, 2020. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- ^ "Steve McQueen wore a Sub No Date 5513". Forums.watchuseek.com. Archived from the original on March 1, 2014. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- ^ "Steve McQueen's Monaco From 'Le Mans' Brings Home $2,208,000 At Phillips, Setting New Heuer Record". Hodinkee. Archived from the original on December 12, 2020. Retrieved December 13, 2020.

- ^ Khan vs Crawford

- ^ Solomon, Michael. "Exclusive: The Secret History of Steve McQueen's Rolex Submariner". Forbes. Archived from the original on February 7, 2019. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- ^ Barrett, Cara (June 5, 2018). "Steve McQueen's Rolex Submariner Is Coming to Auction". bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on November 17, 2019. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- ^ "The McQueen Rolex Submariner". Bob's Watches. September 20, 2018. Archived from the original on February 7, 2019. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- ^ "3rd Moscow International Film Festival (1963)". MIFF. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved December 1, 2012.

Bibliography[]

- Niemi, Robert (October 17, 2013). Inspired by True Events: An Illustrated Guide to More Than 500 History-Based Films, 2nd Edition: An Illustrated Guide to More Than 500 History-Based Films. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-61069-198-7.

- Sanford, Christopher (February 19, 2003). McQueen: The Biography. Lanham, Maryland: Taylor Trade Publications. ISBN 978-0-87833-307-3.

- Terrill, Marshall (1993). Steve McQueen: Portrait of an American Rebel. New York City: Donald I. Fine, Inc. ISBN 978-1-55611-414-4.

- Wright, Kate (2004). Screenwriting is Storytelling: Creating an A-list Screenplay that Sells!. New York City: Perigee Books. ISBN 978-0-399-53024-1.

- Terrill, Marshall (2020). Steve McQueen: In His Own Words. Deerfield, IL: Dalton Watson. ISBN 978-1-85443-271-1.

Further reading[]

- Beaver, Jim. Steve McQueen. Films in Review, August–September 1981.

- Satchell, Tim. McQueen. (Sidgwick and Jackson Limited, 1981) ISBN 0-283-98778-2

- Siegel, Mike. Steve McQueen: The Actor and his Films (Dalton Watson, 2011)

- Nolan, William F. McQueen (Congdon & Weed, 1984)

- McQueen, Steve (November 1966). "Motorcycles: What I like in a bike—and why". Popular Science. 189 (5). pp. 76–81. ISSN 0161-7370.

- Terrill, Marshall. Steve McQueen: Portrait of an American Rebel, (Donald I. Fine, 1993)

- Terrill, Marshall. Steve McQueen: The Last Mile', (Dalton Watson, 2006)

- Terrill, Marshall. Steve McQueen: A Tribute to the King of Cool, (Dalton Watson, 2010)

- Terrill, Marshall. Steve McQueen: The Life and Legacy of a Hollywood Icon, (Triumph Books, 2010)

- Terrill, Marshall. Steve McQueen: In His Own Words, (Dalton Watson, 2020)

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Steve McQueen. |

- Official website

- Steve McQueen: In His Own Words by Marshall Terrill

- Steve McQueen at IMDb

- Steve McQueen at the Internet Broadway Database

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (January 2018) |

- FBI Records: The Vault – Terrence Steven (Steve) McQueen at vault.fbi.gov

- Steve McQueen at Virtual History

- Rare Photos of the King of Cool – slideshow at Life magazine

- Bell System Film "A Family Affair", McQueen's debut, at The AT&T Tech Channel

- The Great Escape – New publication with private photos of the shooting & documents of 2nd unit cameraman Walter Riml

- Photos of the filming The Great Escape, Steve McQueen on the set

- Photos and commentary on Steve McQueen shooting an episode of Wanted: Dead or Alive on the Iverson Movie Ranch

- 1930 births

- 1980 deaths

- 20th-century American male actors

- American male film actors

- American male television actors

- American motorcycle racers

- American people of Scottish descent

- American tang soo do practitioners

- British Touring Car Championship drivers

- California Republicans

- Converts to Christianity

- Deaths from cancer in Mexico

- Deaths from mesothelioma

- Enduro riders

- Former Roman Catholics

- Male actors from Indiana

- Male actors from Indianapolis

- Male actors from Los Angeles

- Male actors from Missouri

- Male Western (genre) film actors

- Military personnel from Indiana

- World record setters in motorcycling

- Neighborhood Playhouse School of the Theatre alumni

- Off-road motorcycle racers

- Off-road racing drivers

- People from Beech Grove, Indiana

- People from Echo Park, Los Angeles

- People from Saline County, Missouri

- Racing drivers from California

- Racing drivers from Indiana

- Racing drivers from Missouri

- United States Marines

- Western (genre) television actors

- World Sportscar Championship drivers