Sukhothai Kingdom

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2012) |

Sukhothai Kingdom อาณาจักรสุโขทัย | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1238–1438 | |||||||||

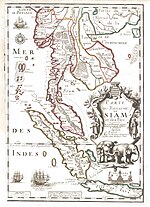

Map of Sukhothai in 1293 during the reign of Ram Khamhaeng. | |||||||||

| Status | Vassal of the Ayutthaya Kingdom (1378–1438/1569[1]) | ||||||||

| Capital | Sukhothai (1238–1347, 1430–1438) Phitsanulok (1347–1430) | ||||||||

| Common languages | Sukhothai language | ||||||||

| Religion | Theravada Buddhism | ||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy | ||||||||

| King | |||||||||

• 1238–1257 | Sri Indraditya | ||||||||

• 1279–1299 | Ramkhamhaeng the Great | ||||||||

• 1347–1368 | Mahathammaracha I | ||||||||

• 1419–1438 | Mahathammaracha IV | ||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||

• Liberation from Lavo | 1238 | ||||||||

• Expansions under Ram Khamhaeng | 1279–1298 | ||||||||

• Became Ayutthayan tributary | 1378 | ||||||||

• Merger into Ayutthaya Kingdom | 1438 | ||||||||

• Maha Thammaracha becomes King of Ayutthaya | 1569[2] | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Thailand Laos Myanmar Malaysia | ||||||||

| History of Thailand |

|---|

|

|

|

The Sukhothai Kingdom (Thai: สุโขทัย, RTGS: Sukhothai, IAST: Sukhodaya, pronounced [sù.kʰǒː.tʰāj] (![]() listen)) was an early kingdom in the area around the city Sukhothai, in north central Thailand. The kingdom existed from 1238 until 1438, and has been commonly described as "the first Thai kingdom" in 20th-century Thai historiography. The ruins of the old capital, now 12 km (7.5 mi) outside Sukhothai in , are preserved as Sukhothai Historical Park and designated a World Heritage Site.

listen)) was an early kingdom in the area around the city Sukhothai, in north central Thailand. The kingdom existed from 1238 until 1438, and has been commonly described as "the first Thai kingdom" in 20th-century Thai historiography. The ruins of the old capital, now 12 km (7.5 mi) outside Sukhothai in , are preserved as Sukhothai Historical Park and designated a World Heritage Site.

Etymology[]

Sukhothai or Sukhodaya is derived from Sanskrit sukha (सुख 'happiness') + udaya (उदय 'rise', 'emergence'), meaning 'dawn of happiness'.

History[]

Mon era[]

According to the Northern Thai Chronicles, Sukhothai (Thai: ศุโขทัย) was founded by Phraya Paliraj, who came from Lavo in 678 CE (40 Chula Sakarat).[3]

Khmer Era[]

The settlement started as a Khmer outpost named Sukhodaya.[4][5][6] During the reign of Khmer Empire, the Khmers built some monuments there, several of them survived in Sukhothai Historical Park such as the Ta Pha Daeng shrine, Wat Phra Phai Luang, and Wat Sisawai.[7] About some 50 kilometer north of Sukhothai is another Khmer military outpost of Si Satchanalai or Sri Sajanalaya.[8][9]

In the mid-13th century, the Tai tribes led by Si Indradit rebelled against the Khmer governor at Sukhodaya and established Sukhothai as an independent Tai state and remained the center of Tai power until the end of the fourteenth century.[4][5][10]

Liberation from Lavo[]

Prior to the 13th century, Tai kingdoms had existed in the northern highlands including the Ngoenyang Kingdom of the Tai Yuan people (centred on Chiang Saen and the predecessor of the Lan Na), and the Heokam Kingdom of the Tai Lue people (centred on Chiang Hung (today Jinghong in China). Sukhothai had been a trade centre and part of Lavo (present day Lopburi), which was under the domination of the Khmer Empire. The migration of Tai people into the upper Chao Phraya valley was somewhat gradual.

Two friends, Pho Khun Bangklanghao and Pho Khun Pha Mueang revolted against the Khmer Empire governor of Sukhothai.[10]:195–196 Khun, before becoming a Thai feudal title, was a Tai title for a ruler of a fortified town and its surrounding villages, together called a mueang; in older usage prefixed by pho (พ่อ) "father",[12] (comparable in sound and meaning to rural English Paw). Bangklanghao ruled Sukhothai as Sri Indraditya – and began the Phra Ruang Dynasty—he expanded his primordial kingdom to the bordering cities. At the end of his reign in 1257, the Sukhothai kingdom covered the entire upper valley of the Chao Phraya River (then known simply as แม่น้ำ (mae nam, 'mother of waters'), the generic Thai name for rivers.)

Traditional Thai historians considered the foundation of the Sukhothai Kingdom as the beginning of their nation because little was known about the kingdoms prior to Sukhothai. Modern historical studies demonstrate that Thai history began before Sukhothai. Yet the foundation of Sukhothai is still a celebrated event.

Expansions under Ram Kamhaeng[]

Pho Khun Ban Muang and his brother Ram Khamhaeng expanded the Sukhothai kingdom. To the south, Ramkamhaeng subjugated the kingdom of Supannabhum and Sri Thamnakorn (Tambralinga) and, through Tambralinga, adopted Theravada as state religion. Traditional history described the extension of Sukhothai in a great fashion and the accuracy of these claims is disputed. To the north, Ramkamhaeng put Phrae and Muang Sua (Luang Prabang) under tribute.

To the west, Ramkhamhaeng helped the Mon under Wareru (who is said to have eloped with Ramkamhaeng's daughter) to free themselves from Pagan control and established a kingdom at Martaban Kingdom (they later moved to Pegu). So, Thai historians considered the Kingdom of Martaban a Sukhothai tributary. However, in practice, such Sukhothai domination may not have extended that far.

With regard to culture, Ramkhamhaeng requested the monks from Sri Thamnakorn to propagate the Theravada religion in Sukhothai. In 1283, the Sukhothai script was invented by Ramkamhaeng, formulating into the controversial Ramkamhaeng Stele discovered by Mongkut 600 years later. The Sukhothai script later developed into the modern Thai script of today.

It was also this time that the first relation with Yuan dynasty was formulated and Sukhothai began sending trade missions to China. The well-known exported good of Sukhothai was the Sangkalok (Song Dynasty pottery) – the only period that Siam produced Chinese-styled ceramics and fell out of use by the 14th century.

Decline and domination of Ayutthaya[]

By the beginning of the fourteenth century, the Thai of Sukhothai controlled most of present-day Thailand. Only the eastern provinces remained under Khmer control.[10]:223 After the death of Ramkhamhaeng, the Sukhothai tributaries broke away. Ramkhamhaeng was succeeded by his son Loethai. The vassal kingdoms, first Uttaradit in the north, then soon after the Laotian kingdoms of Luang Prabang and Vientiane (Wiangchan), liberated themselves from their overlord. In 1319 the Mon state to the west broke away, and in 1321 Lanna placed Tak, one of the oldest towns under the control of Sukhothai, under its control. To the south the powerful city of Suphanburi also broke free early in the reign of Loethai. Thus the kingdom was quickly reduced to its former local importance only.

In 1349, the armies from Ayutthaya Kingdom invaded and put Sukhothai under her tributary.[10]:222 Then, in 1378, King Luethai had to submit to this new power as a vassal state.[13]:29–30

In 1424, after the death of Sailuethai, his sons Phaya Ram and Phaya Ban Muang (Mahathammaracha IV) fought for the throne. Intharacha of Ayutthaya intervened and further divided the kingdom between the two. When Mahathammaracha IV died in 1438, king Borommaracha II of Ayutthaya installed his son Ramesuan (the future king Borommatrailokanat of Ayutthaya) as viceroy of Sukhothai, presumably accompanied by Ayutthayan administrative staff and a military garrison, thus marking the end of Sukhothai as an independent kingdom.[14]

The Silajaruek of Sukhothai are hundreds of stone inscriptions that form a historical record of the period. Among the most important inscriptions are Silajaruek Pho Khun Ramkhamhaeng (Stone Inscription of King Ramkhamhaeng), Silajaruek Wat Srichum (an account on history of the region itself and of Sri Lanka), and Silajaruek Wat Pamamuang (a Politico-Religious record of King Loethai).

Gradual merger with Ayutthaya[]

It was however not simply annexed and incorporated into the Ayutthayan Empire, rather did the two mandalas and their traditions gradually merge during the 15th and 16th centuries. Sukhothai's warfare, administration, architecture, religious practice and language influenced the Ayutthayan ones significantly. As the Ayutthaya Kingdom did not yet have a centralised administration, the former territories of Sukhothai, now termed as the "northern cities" or Mueang Nuea, continued to be ruled by local aristocrats under Ayutthaya's overlordship. In modern terms, this state may be described as a sort of "federation". The most important "northern city" was now Phitsanulok, as Sukhothai proper had massively lost importance. Northern nobles linked themselves with the Ayutthayan elite through marriage alliances and northern military leaders served prominently in Ayutthaya's army as the military tradition of Sukhothai was considered to be tougher.[15]

From 1456 to 1474, the former territories of Sukhothai were the object of a war between Ayutthaya and the Northern Thai kingdom of Lan Na. In 1462 the city-state of Sukhothai rebelled against Ayutthaya and allied itself with its enemy, Lan Na. During this time, Phitsanulok served as the "second capital" of the Ayutthaya Kingdom, and in 1463 king Borommatrailokanat even moved his residence there, presumably to be closer to the frontline. Contemporary Portuguese traders described Ayutthaya and Phitsanulok as "twin states". Northern nobles descending from old Sukhothai's elite often played the role of kingmakers in Ayutthaya succession conflicts. In 1569 Mahathammaracha, then governor of Phitsanulok and viceroy of the Northern cities, who claimed to descend from the old Sukhothai dynasty, ascended the Ayutthayan throne.[15]

After the Battle of Sittaung River in 1583, Naresuan, then uparaja (viceroy) of Ayutthaya and ruler of Phitsanulok, forcibly relocated people from the northern cities of Phitsanulok, Sukhothai, Phichai, Sawankhalok (Si Satchanalai), Kamphaeng Phet, Phichit, and Prabang to the region surrounding Ayutthaya.[16][17]

Kings[]

Historiography[]

The story of Sukhothai was incorporated into Thailand's "national history" in the late 19th century by King Mongkut, Rama IV, as a historical work presented to the British diplomatic mission. King Mongkut is considered the champion of Sukhothai narrative history based on his finding the Number One Stone Inscription, the 'first evidence' telling the history of Sukhothai.[18]

From then on, as a part of modern nation building process, modern national Siamese or Thai history comprises the history of Sukhothai. Sukhothai was said to be the 'first national capital',[19] followed by Ayutthaya, Thonburi until Rattanakosin or today Bangkok. Sukhothai history was crucial among Siam/ Thailand's 'modernists', both 'conservative' and 'revolutionary'.[citation needed] Rama IV (King Mongkut) said that he found 'the first Stone Inscription' in Sukhothai, telling story of Sukhothai's origin, heroic kings such as Ram Khamhaeng, administrative system and other developments, considered as the 'prosperous time' of the kingdom.

Sukhothai history became important even after the Revolution of 1932. Researches and writings on Sukhothai history were abundant.[20] Details derived from the inscription were studied and 'theorised'.[21] One of the most well-known topics was Sukhothai's 'democracy' rule. Story of the close relationship between king and his people, vividly described as 'father-son' relationship,[22] the 'seed' of Thai Democracy. However the change in ruling style took place when later society embraced 'foreign' tradition, Khmer's Angkor tradition, influenced by Hinduism and 'mystic' Mahayana Buddhism. The story of Sukhothai became the model of 'freedom'. Jit Bhumisak, a 'revolutionary' scholar, also saw Sukhothai period as the beginning of the Thai people's liberation movement from their foreign ruler, Angkor.

During military rule, from the 1950s, Sukhothai was placed in Thai national curriculum. Sukhothai became model of 'father-son' rule, described as 'Thai Democracy', free from 'foreign ideology'; Angkorian tradition compared to communism. Other Sukhothai aspects were investigated seriously, such as commoner and slave status, and economic situation. These topics, said, were on stage of ideological thoughts fighting during the Cold War and civil insurgency times in 1960-1970s.

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Chris Baker; Pasuk Phongpaichit (2017). A History of Ayutthaya. Cambridge University Press. p. 76.

But 1569 was also the final act of the merger between Ayutthaya and the Northern Cities.

- ^ Chris Baker; Pasuk Phongpaichit (2017). A History of Ayutthaya. Cambridge University Press. p. 76.

But 1569 was also the final act of the merger between Ayutthaya and the Northern Cities.

- ^ พระราชพงศาวดารเหนือ (in Thai), โรงพิมพ์ไทยเขษม, 1958, retrieved 1 March 2021

- ^ Jump up to: a b Swearer, Donald K. (1 January 1995). The Buddhist World of Southeast Asia. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-2459-9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wicks, Robert S. (31 May 2018). Money, Markets, and Trade in Early Southeast Asia: The Development of Indigenous Monetary Systems to AD 1400. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-1947-9.

- ^ Olsen, Brad (2004). Sacred Places Around the World: 108 Destinations. CCC Publishing. ISBN 978-1-888729-10-8.

- ^ orientalarchitecture.com. "Ta Pha Daeng Shrine, Sukhothai, Thailand". Asian Architecture. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ "Si Satchanalai - Jim Wageman". www.jimwagemanphoto.com. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ "Chaliang Zone of the Si Satchanalai Historical Park". www.renown-travel.com. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Coedès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella (ed.). The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. Translated by Cowing, Susan Brown. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- ^ "Seated Buddha in "Maravijaya"". The Walters Art Museum.

- ^ Terwiel, Barend Jan (1983). "Ahom and the Study of Early Thai Society" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. Siamese Heritage Trust. JSS Vol. 71.0 (digital): image 4. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

khun: ruler of a fortified town and its surrounding villages, together called a mu'ang. In older sources the prefix ph'o ("father") is sometimes used as well.

- ^ Chakrabongse, C., 1960, Lords of Life, London: Alvin Redman Limited

- ^ David K. Wyatt (2004). Thailand: A Short History (2nd ed.). Silkworm Books. p. 59.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Chris Baker; Pasuk Phongpaichit (2014). A History of Thailand (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 10.

- ^ Phisēt Čhīačhanphong (2003). พระมหาธรรมราชากษัตราธิราช. กรุงเทพฯ: สำนักพิมพ์มติชน. p. 57. ISBN 974-322-818-7.

- ^ Chris Baker; Pasuk Phongpaichit (2017). A History of Ayutthaya. Cambridge University Press. p. 77.

- ^ Lingat, R. (1933). "History of Wat Pavaranivesa" (Digital). Journal of the Siam Society. Siam Heritage Trust. 26.1c. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

In 1837 King Phra Nang Klao made Prince Mongkut Abbot of Wat Pavaraniveca, situated close to the enceinte wall, in the northern part of the city. This monastery had been founded about ten years previously by Prince Cakti, who had been raised to the rank of Second King on the ascension of Phra Nang Klao, his nephew (1824-1832).

- ^ Cœdès, G. (1921). "The Origins of the Sukhodaya Dynasty" (Digital). Journal of the Siam Society. Siam Heritage Trust. 14.1b: 1. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

The dynasty which reigned during a part of the 13th and the first half of the 14th centuries at Sukhodaya and at , on the upper Menam Yom, is the first historical Siamese dynasty. It has a double claim to this title, both because it cradle was precisely in the country designated by foreigners as "Siam" (Khmer: Syam; Chinese Sien, etc.), and because it is this dynasty which, by freeing the Thai principalities from the Cambodian yoke and by gradually extending its conquests as far as the Malay Peninsula, paved the way for the formation of the Kingdom of Siam properly so called.

- ^ Bradley, C.B. (1909). "The Oldest Known Writing in Siamese; the inscription of Phra Ram Khamhaeng of Sukhothai, 1293 A.D." (Digital). Journal of the Siam Society. Siam Heritage Trust. 6.1b. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ "Epigraphical and historical studies, nos. 1-24 published in the Journal of the Siam Society from 1968-1979"--Pref. Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Inscriptions, Thai. Notes: English and Thai; some Pali (in roman).

- ^ Sarasin Viraphol (1977). "Law in traditional Siam and China: A comparative study" (Digital). Journal of the Siam Society. Siam Heritage Trust. 65.1c. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

Further reading[]

- Ekachai, Sanitsuda (28 September 2019). "Opening minds with an ancient 'mandala'". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sukhothai Kingdom. |

- Sukhothai Kingdom

- Former countries in Thai history

- Former kingdoms

- Indianized kingdoms

- Sukhothai Province

- 13th century in Siam

- 14th century in Siam

- 15th century in Siam

- 16th century in Siam

- States and territories established in 1238

- States and territories established in 1438

- 1238 establishments in Asia

- 1438 disestablishments in Asia

- 13th-century establishments in Siam

- 15th-century disestablishments in Siam

- Former monarchies of Southeast Asia