Sullivan's Island, South Carolina

Sullivan's Island, South Carolina | |

|---|---|

Town | |

Sullivan's Island viewed from Fort Moultrie | |

| Coordinates: 32°45′48″N 79°50′16″W / 32.76333°N 79.83778°WCoordinates: 32°45′48″N 79°50′16″W / 32.76333°N 79.83778°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | South Carolina |

| County | Charleston |

| Settled | 17th century (as O'Sullivan's Island) |

| Named for | Captain Florence O'Sullivan |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Patrick O'Neil |

| Area | |

| • Total | 3.44 sq mi (8.91 km2) |

| • Land | 2.50 sq mi (6.47 km2) |

| • Water | 0.94 sq mi (2.44 km2) |

| Elevation | 9 ft (3 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 1,791 |

| • Estimate (2019)[2] | 1,924 |

| • Density | 770.22/sq mi (297.38/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 29482 |

| Area code(s) | 843, 854 |

| FIPS code | 45-70090[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1231842[4] |

| Website | sullivansisland-sc |

Sullivan's Island is a town and island in Charleston County, South Carolina, United States, at the entrance to Charleston Harbor, with a population of 1,791 at the 2010 census.[5] The town is part of the Charleston metropolitan area, and is considered a very affluent suburb of Charleston.

Sullivan's Island was the point of entry for approximately 40 to 50 percent of the 400,000 enslaved Africans brought to Colonial America, meaning that 99% of all African Americans have ancestors that came through the island.[6][7][8] It has been likened to Ellis Island, the 19th-century reception point for immigrants in New York City.[9] During the American Revolution, the island was the site of a major battle at Fort Sullivan on June 28, 1776, since renamed Fort Moultrie in honor of the American commander at the battle.

On September 23, 1989, Hurricane Hugo came ashore near Sullivan's Island; few people were prepared for the destruction that followed in its wake. The eye of the hurricane passed directly over Sullivan's Island. The Ben Sawyer Bridge was a casualty, breaking free of its locks. Before the storm was over, one end of the bridge was in the water and the other was pointing skyward. Sullivan's Island police chief, Jack Lilien, was the last person to leave the island before the bridge gave way.

History[]

The island was known as O'Sullivan's Island,[clarification needed] named for Captain Florence O'Sullivan, who was stationed here as a lookout in the late 17th century. O'Sullivan was captain of one of the ships in the first fleet to establish the colonial settlement of Charles Town. In 1671, he became surveyor general. He appears in the earliest record of Irish immigration to the Carolinas, mentioned as being taken on "at Kingsayle (Kinsale) in Ireland".

Sullivan's Island was used as a quarantine station for enslaved Africans, who were housed in various "pest houses" on the island and checked for communicable diseases before they were transported to Charleston for sale at public auction.[10] Sullivan's Island was the port of entry for over 40% of the estimated 400,000 enslaved Africans transported to Colonial America, making it the largest slave port in North America. It is estimated that more than half, if not all, of all African Americans have ancestors who passed through Sullivan's Island.[10]

"There is no suitable memorial, or plaque, or wreath or wall, or park or skyscraper lobby," writer Toni Morrison said in 1989.[11] "There's no 300-foot tower, there's no small bench by the road."

On July 26, 2008, the Toni Morrison Society dedicated a small, black, steel bench on Sullivan's Island to the memory of the Africans forced into slavery, one of several which are planned.[10] The memorial was privately funded.[12]

In 2009, the National Park Service installed a commemorative marker at Fort Moultrie describing the Sullivan's Island Quarantine Station. The text on the plaque reads:

This is Sullivan's Island

A place where...Africans were brought to this country under extreme conditions of human bondage and degradation. Tens of thousands of captives arrived on Sullivan's Island from the West African shores between 1700 and 1775. Those who remained in the Charleston community and those who passed through this site account for a significant number of the African-Americans now residing in these United States. Only through God's blessings, a burning desire for justice, and persistent will to succeed against monumental odds, have African-Americans created a place for themselves in the American mosaic.

A place where...We commemorate this site as the entry of Africans who came and who contributed to the greatness of our country. The Africans who entered through this port have moved on to meet the challenges created by injustices, racial and economic discrimination, and withheld opportunities. Africans and African-Americans, through the sweat of their brow, have distinguished themselves in the Arts, Education, Medicine, Politics, Religion, Law, Athletics, Research, Artisans and Trades, Business, Industry, Economics, Science, Technology and Community and Social Services.

A place where...This memorial rekindles the memory of a dismal time in American history, but it also serves as a reminder for a people who – past and present, have retained the unique values, strength and potential that flow from our West African culture which came to this nation through the middle passage.

Erected in 1990 by the S.C. Department of Archives and History. The Charleston Club of S.C. and the Avery Research Center.

Pursuant to a request from the South Carolina General Assembly as Evidenced in concurrent resolution S. 719, Adopted June 3, 1990.[13]

Albert Wheeler Todd, an architect from Charleston, designed a town hall for the island.[14] For most of its history, the town, located on the southwest half of the island, was known as "Moultrieville". Later, Atlanticville, a community on the north-east of the islands, merged with Moultrieville and together the two became the town of Sullivan's Island. In 1962, the new Charleston Light was built.

In May 2006, the Town of Sullivan's Island became the first municipality in South Carolina to ban smoking in all public places. The ordinance passed 4–2 and the ban went into effect in June.[15]

The Atlanticville Historic District, Battery Gadsden, Battery Thomson, Fort Moultrie Quartermaster and Support Facilities Historic District, Moultrieville Historic District, Dr. John B. Patrick House, Sullivan's Island Historic District, and U.S. Coast Guard Historic District are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[16]

Fort Moultrie[]

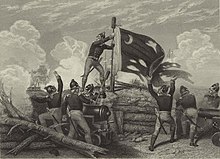

On June 28, 1776, an incomplete fort was held by South Carolinian forces under Colonel William Moultrie against an invasion by a British force under the command of Henry Clinton sailing with Commodore Sir Peter Parker's Royal Navy fleet. The British cannonade proved to have no effect on the sand-filled palmetto log walls of the fort; the only fatalities were the result of those shots that carried over the walls.

During this battle, a flag designed by Moultrie flew over the fortress; it was dark blue with a crescent moon on it bearing the word "liberty". When this flag was shot down, Sergeant William Jasper reportedly picked it up and held it aloft, rallying the troops until a new standard could be provided. Because of the importance of this pivotal battle, that flag became symbolic of liberty in South Carolina, the South, and the nation as a whole.

The Battle of Sullivan's Island was commemorated by the addition of a white palmetto tree to the flag used to rally that day, known as the Moultrie Flag. This was used as the basis of the state flag of South Carolina. The victory is celebrated and June 28 is known as Carolina Day.

The history of the island has been dominated by Fort Moultrie, which, until its closure in the late 1940s, served as the base of command for the defense of Charleston. After World War II, the Department of Defense concluded that such coastal defense installations were no longer needed, given current technology and style of war. It is now used as heritage tourism.

Geography[]

Sullivan's Island is located along the Atlantic Ocean near the center of Charleston County. The town is bordered to the west by the entrance to Charleston Harbor, to the north by Cove Inlet and the Intracoastal Waterway, and to the east by Breach Inlet and Swinton Creek. The Ben Sawyer Bridge connects Sullivan's Island to Mount Pleasant to the north. A bridge spanning Breach Inlet connects it to Isle of Palms to the east. By road it is 9 miles (14 km) north and then west into Charleston.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the town of Sullivan's Island has a total area of 3.4 square miles (8.9 km2), of which 2.5 square miles (6.5 km2) is land and 0.93 square miles (2.4 km2), or 27.36%, is water.[5]

Airport[]

The town of Sullivan's Island is served by the Charleston International Airport. It is located in the City of North Charleston and is about 12 mi (19 km) northwest of Sullivan's Island. It is the busiest passenger airport in South Carolina (IATA: CHS, ICAO: KCHS). The airport shares runways with the adjacent Charleston Air Force Base. Charleston Executive Airport is a smaller airport located in the John's Island section of the city of Charleston and is used by noncommercial aircraft. Both airports are owned and operated by the Charleston County Aviation Authority.

Demographics[]

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1960 | 1,358 | — | |

| 1970 | 1,426 | 5.0% | |

| 1980 | 1,867 | 30.9% | |

| 1990 | 1,623 | −13.1% | |

| 2000 | 1,911 | 17.7% | |

| 2010 | 1,791 | −6.3% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 1,924 | [2] | 7.4% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[17] | |||

As of the census[3] of 2000, there were 1,911 people, 797 households, and 483 families residing in the town. The population density was 787.2 people per square mile (303.6/km2). There were 1,045 housing units at an average density of 430.5 per square mile (166.0/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 98.74% White, 0.63% African American, 0.05% Native American, 0.16% Asian, and 0.42% from race were 0.84% of the population. .

There were 797 households, out of which 29.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 50.9% were married couples living together, 7.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 39.3% were non-families. 29.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 7.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.40 and the average family size was 3.01.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 24.0% under the age of 18, 5.0% from 18 to 24, 29.0% from 25 to 44, 31.0% from 45 to 64, and 10.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 41 years. For every 100 females, there were 100.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 97.7 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $72,955, and the median income for a family was $96,455. Males had a median income of $58,571 versus $41,029 for females. The per capita income for the town was $49,427. About 1.4% of families and 4.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 2.2% of those under age 18 and 0.9% of those age 65 or over.

Sullivan's Island has some of the highest per capita real estate costs in the United States. Although not the most expensive in the region, home values on Sullivan's Island, based on the small size of the island and number of regular residents, makes it one of the priciest locations.

Ethnicity[]

As of 2016 the largest self-reported ancestries/ethnicities in Sullivan's Island, South Carolina were:[18]

| hideLargest ancestries (2016) | Percent |

|---|---|

| English | 19.5% |

| German | 14.0% |

| Irish | 12.6% |

| "American" | 11.5% |

| French | 10.0% |

| Scottish | 6.0% |

| Italian | 3.4% |

| Russian | 2.8% |

| Polish | 2.0% |

| Dutch | 1.6% |

Literary references[]

- The writer Edgar Allan Poe was stationed at Fort Moultrie from November 1827 to December 1828.[19] The island is a setting for much of his short story "The Gold-Bug" (1843). In Poe's short story "The Balloon-Hoax", a gas balloon (forerunner of the dirigible) is piloted by eight men, six of them making independent diary entries, and describes a trip from Northern Wales to Fort Moultrie, Sullivan's Island over the course 75 hours. (Written in a dry, scientific style, Poe's account was published as fact in a New York City newspaper in 1844 and retracted three days later.) Today, the town library on Sullivan's Island, situated in a refurbished military battery, is named after the poet, and streets such as Raven (after his narrative poem "The Raven" published in 1845) and Gold Bug avenues commemorate his works. His poem Annabel Lee is said to be written about a girl Poe fell in love with when stationed in Fort Moultrie in the early 1830s.[20]

- The novel Sullivan's Island by Dorothea Benton Frank, is set here.

- Pat Conroy set his semi-autobiographical memoir The Boo (1970) and the novel Beach Music (1995) here. He also features Sullivan's Island in his novel South of Broad (2009).

- In Lawrence Hill's novel, The Book of Negroes, the main character, Aminata Diallo, passes through Sullivan's Island in 1757 at the age of 11 after being kidnapped in Mali and sold into slavery.

Other references[]

E. Lee Spence, a pioneer underwater archaeologist, was a longtime resident of Sullivan's Island. In the 1960s and 1970s, he discovered many shipwrecks along its shores. Those discoveries included the Civil War blockade runners , , Stono, , , and the (also known as the Colt).

In 1981, adventure novelist and marine archaeologist Clive Cussler and his organization, the National Underwater and Marine Agency, discovered the wreck of the blockade runner off Sullivan's Island.

Several districts and properties on Sullivans' Island have been listed in the National Register of Historic Places: Atlanticville Historic District,[21] Moultrieville Historic District,[22] Sullivans Island Historic District,[23] Fort Moultrie Historic District,[24] U. S. Coast Guard Historic District,[25] Battery Gadsden[26] and Battery Thomson.[27]

See also[]

- Battle of Sullivan's Island

- John Henry Devereux, a South Carolina architect who had the largest mansion on the island

References[]

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (G001): Sullivan's Island town, South Carolina". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ IBW21 (2020-02-11). "The Erasure of the History of Slavery at Sullivan's Island". Institute of the Black World 21st Century. Retrieved 2021-07-13.

- ^ Twitty, Michael, 1977- (August 2017). The cooking gene : a journey through African American culinary history in the Old South (First ed.). New York, NY. ISBN 978-0-06-237929-0. OCLC 971130586.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ "Nearly 1,000 Cargos: The Legacy of Importing Africans into Charleston". Charleston County Public Library. 2018-10-05. Retrieved 2021-07-13.

- ^ "African Slave Traditions Live On in U.S.", CNN.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Morekis, Jim (February 2018). Coastal Carolinas. Avalon Travel (Moon). p. 170. ISBN 978-1-64049-245-5. Retrieved 2018-11-20.

- ^ Morrison, Toni. "a bench by the road". uuworld.org. Retrieved 2014-04-15.

- ^ Lee, Felicia R. (July 28, 2008). "Bench of Memory at Slavery's Gateway". The New York Times.

- ^ "What You Need to Know about Slavery and Sullivan's Island". Black Then. 24 May 2018.

- ^ The Buildings of Charleston: A Guide to the City's Architecture By Jonathan H. Poston, page 316

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-07-19. Retrieved 2006-11-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "American FactFinder – Results". factfinder.census.gov. U. S. Census – Bureau. Archived from the original on 2020-02-13. Retrieved 2017-12-24.

- ^ Sova, Dawn B. Edgar Allan Poe: A to Z. New York: Checkmark Books, 2001: 98. ISBN 0-8160-4161-X.

- ^ "Chasing Poe's ghost in Charleston". Baltimore Sun. October 7, 2014.

- ^ "SCDAH". Nationalregister.sc.gov. 2007-09-06. Retrieved 2014-04-15.

- ^ "SCDAH". Nationalregister.sc.gov. 2007-09-06. Retrieved 2014-04-15.

- ^ "SCDAH". Nationalregister.sc.gov. 2007-09-06. Retrieved 2014-04-15.

- ^ "SCDAH". Nationalregister.sc.gov. 2007-09-06. Retrieved 2014-04-15.

- ^ "SCDAH". Nationalregister.sc.gov. 1973-06-19. Retrieved 2014-04-15.

- ^ "SCDAH". Nationalregister.sc.gov. 1974-06-25. Retrieved 2014-04-15.

- ^ "SCDAH". Nationalregister.sc.gov. 1974-06-25. Retrieved 2014-04-15.

Further reading[]

- Gadsden Cultural Center; McMurphy, Make; Williams, Sullivan (October 4, 2004). Sullivan's Island/Images of America. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-7385-1678-3.

- "Hurricane Hugo: A Landmark in Time" (2009). The Post and Courier, Charleston, SC-Evening Post Publishing Company. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-9825154-0-2.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sullivan's Island, South Carolina. |

- Official website

- The Island Eye News, local Sullivan's Island publication

- Real Estate Listings, Homes On Sullivan's Island for Sale

- American Revolution

- Edgar Allan Poe

- Populated coastal places in South Carolina

- Populated places established in the 17th century

- Towns in Charleston County, South Carolina

- Towns in South Carolina