Tarring and feathering

The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the English-speaking world and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (July 2021) |

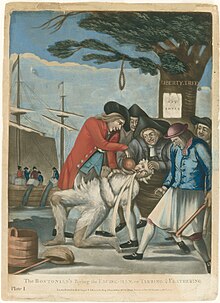

Tarring and feathering is a form of public torture and punishment used to enforce unofficial justice or revenge. It was used in feudal Europe and its colonies in the early modern period, as well as the early American frontier, mostly as a type of mob vengeance.

The victim would be stripped naked, or stripped to the waist. Wood tar (sometimes hot) was then either poured or painted onto the person while they were immobilized. Then the victim either had feathers thrown on them or was rolled around on a pile of feathers so that they stuck to the tar.

The image of a tarred-and-feathered outlaw remains a metaphor for severe public criticism.[3]

History[]

The earliest mention of the punishment appears in orders that Richard I of England issued to his navy on starting for the Holy Land in 1189. "Concerning the lawes and ordinances appointed by King Richard for his navie the forme thereof was this ... item, a thiefe or felon that hath stolen, being lawfully convicted, shal have his head shorne, and boyling pitch poured upon his head, and feathers or downe strawed upon the same whereby he may be knowen, and so at the first landing-place they shall come to, there to be cast up" (transcript of original statute in Hakluyt's Voyages, ii. 21).[4][5]

A later instance of this penalty appears in Notes and Queries (series 4, vol. v), which quotes James Howell writing in Madrid in 1623 of the "boisterous Bishop of Halberstadt, a German Protestant military leader... having taken a place where there were two monasteries of nuns and friars, he caused divers feather beds to be ripped, and all the feathers thrown into a great hall, whither the nuns and friars were thrust naked with their bodies oiled and pitched and to tumble among these feathers, which makes them here (Madrid) presage him an ill-death."[4] (The Bishop was apparently Christian the Younger of Brunswick.)

In 1696, a London bailiff attempted to serve process on a debtor who had taken refuge within the precincts of the Savoy. The bailiff was tarred and feathered and taken in a wheelbarrow to the Strand, where he was tied to a maypole that stood by what is now Somerset House as an improvised pillory.[4]

Early America[]

The practice of tarring and feathering was exported to the Americas, gaining popularity in the mid-18th century. Throughout the 1760s it saw increased usage as a means of protesting the Townshend Revenue Act and those who sought to enforce it.[6] After a period of few tarrings and featherings between 1770 and 1773, the passage of the Tea Act in May 1773 led to a resurgence of incidents.[6]

In 1766, Captain William Smith was tarred, feathered, and dumped into the harbor of Norfolk, Virginia by a mob that included the town's mayor. A vessel picked him out of the water just as his strength was giving out. He survived and was later quoted as saying that they "dawbed my body and face all over with tar and afterwards threw feathers on me." Smith was suspected of informing on smugglers to the British customs agents, as was the case with most other tar-and-feathers victims in the following decade.[7]

The practice appeared in Salem, Massachusetts in 1768, when mobs attacked low-level employees of the customs service with tar and feathers. In October 1769, a mob in Boston attacked a customs service sailor the same way, and a few similar attacks followed through 1774. Customs Commissioner John Malcolm was tarred and feathered on two occasions. Firstly, in November 1773 he was targeted by sailors in Portsmouth, New Hampshire before undergoing a similar, albeit arguably more violent, ordeal in Boston in January 1774.[8][9] Malcom was stripped, whipped, beaten, tarred, and feathered for several hours. He was then taken to the Liberty Tree and forced to drink tea until he vomited.[6]

In February 1775, Dr. Abner Bebee, a Loyalist of East Haddam, Connecticut, was tarred and feathered before being taken to a hog sty and covered in dung. Hog dung was then smeared in his eyes and forced down his throat. Dr. Bebee was subjected to this as a perceived punishment for expressing pro-British sentiment by his local Committee of Safety.[9][10]

A particularly violent act of tarring and feathering took place in August 1775 northeast of Augusta, Georgia.[11] Landowner and loyalist Thomas Brown was confronted on his property by members of the Sons of Liberty. After putting up some resistance, Brown was beaten with a rifle, fracturing his skull. He was then stripped and tied to a tree. Hot pitch was poured over him before being set alight, charring two of his toes to stubs. Brown was then feathered by the Sons of Liberty, who then took a knife to his head and began scalping him.[11]

Such acts associated the punishment with the Patriot side of the American Revolution.[6]

An exception occurred in March 1775, when a number of soldiers and officers from the 47th Regiment of Foot inflicted the same treatment on Thomas Ditson, a Billerica, Massachusetts man who attempted to buy a musket from one of the regiment's soldiers.[12] Ditson was tarred and feathered before having a placard reading "American Liberty: A Speciment [sic] of Democracy" hung around his neck whilst fife and drummers played "Yankee Doodle".[6]

During the Whiskey Rebellion, local farmers inflicted the punishment on federal tax agents.[6] Beginning on September 11, 1791, western Pennsylvania farmers rebelled against the federal government's taxation on western Pennsylvania whiskey distillers. Their first victim was reportedly a recently appointed tax collector named Robert Johnson. He was tarred and feathered by a disguised gang in Washington County. Other officials who attempted to serve court warrants on Johnson's attackers were whipped, tarred, and feathered. Because of these and other violent attacks, the tax went uncollected in 1791 and early 1792. The attackers modeled their actions on the protests of the American Revolution.[13]

There is no known case of a person dying from being tarred and feathered during this period.[citation needed]

19th century[]

Joseph Smith, founder of the Latter Day Saint movement, was dragged from his home during the night of March 24, 1832, by a group of men who stripped and beat him before tarring and feathering him. His wife and infant child were knocked from their bed by the attackers and were forced from the home and threatened. (The infant died several days later from exposure.) Smith was left for dead, but limped back to the home of friends. They spent much of the night scraping the tar from his body, leaving his skin raw and bloody. The following day, Smith spoke at a church devotional meeting and was reported to have been covered with raw wounds and still weak from the attack.[14][citation needed]

In 1851, a Know-Nothing mob in Ellsworth, Maine, tarred and feathered Swiss-born Jesuit priest Father John Bapst in the midst of a local controversy over religious education in grammar schools. Bapst fled Ellsworth to settle in nearby Bangor, Maine, where there was a large Irish-Catholic community, and a local high school there is named for him.[15]

20th century[]

Tarring and feathering was not restricted to men. The November 27, 1906 Ada, Oklahoma Evening News reports that a vigilance committee consisting of four young married women from East Sandy, Pennsylvania corrected the alleged evil conduct of their neighbor Mrs. Hattie Lowry in whitecap style. One of the women was a sister-in-law of the victim. The women appeared at Mrs. Lowry's home in open day and announced that she had not heeded the spokeswoman and leader. Two women held Mrs. Lowry to the floor while the other two smeared her face with stove polish until it was completely covered. They then poured thick molasses upon her head and emptied the contents of a feather pillow over the molasses. The women then marched the victim to a railroad camp, tied by the wrists, where two hundred workmen stopped work to watch the spectacle. After parading Mrs. Lowry through the camp, the women tied her to a large box where she remained until a man released her. Three of the women involved were arrested, pleaded guilty and each paid a $10.00 fine.[16]

There were several examples of tarring and feathering of African Americans in the lead-up to World War I in Vicksburg, Mississippi.[17] According to William Harris, this was a relatively rare form of mob punishment to Republican African-Americans in the post-bellum U.S. South, as its goal was typically pain and humiliation rather than death.[17]

During World War I, anti-German sentiment was widespread in the United States and many German-Americans were attacked. For example, in August 1918 a German-American farmer, John Meints (pictured in lead) of Luverne, Minnesota, was captured by a group of men, taken to the nearby South Dakota border and tarred and feathered – for allegedly not supporting war bonds. Meints sued his assailants and lost, but on appeal to a federal court he won, and in 1922 settled out of court for $6,000.[18] In March 1922, a German-born Catholic priest in Slaton, Texas, Joseph M. Keller, who had been harassed by local residents during World War I due to his ethnicity, was accused of breaking the seal of confession and tarred and feathered. Thereafter Keller served a Catholic parish in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.[19]

Future Australian senator Fred Katz – a socialist and anti-conscriptionist of German parentage – was publicly tarred and feathered outside his office in Melbourne in December 1915.[20] A week before the 1919 Australian federal election, former Labor MP John McDougall was kidnapped by a group of about 20 ex-soldiers in Ararat, Victoria, and subsequently tarred and feathered before being dumped in the town's streets. He had earlier been revealed as the author of an anti-war poem that was perceived as insulting Australia's soldiers. Six men were charged with inflicting grievous bodily harm, but pleaded down to common assault and were fined £5 each. Many newspapers supported their actions.[21]

A group of black-robed Knights of Liberty (a faction of the KKK) tarred and feathered seventeen members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in Oklahoma in 1917, during an incident known as the Tulsa Outrage.[22] In the 1920s, vigilantes were opposed to IWW organizers at California's harbor of San Pedro. They kidnapped at least one organizer, subjected him to tarring and feathering, and left him in a remote location.[citation needed]

The Wednesday, May 28, 1930 edition of the Miami Daily News-Record (Miami, Oklahoma) contains on its front page the arrests of five brothers (Isaac, Newton, Henry, Gordon and Charles Starns) from Louisiana accused of tarring and feathering Dr. S. L. Newsome, who was a prominent dentist. This was in retaliation for the dentist having an affair with one of the brother's wives.[citation needed]

Similar tactics were also used by the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) during the early years of the Troubles. Many of the victims were women accused of being in romantic relationships with policemen or British soldiers.[23][24]

21st century[]

In August 2007, loyalist groups in Northern Ireland were linked to the tarring and feathering of an individual accused of drug-dealing.[25]

In June 2020, multiple graves and memorials to Confederate soldiers at Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis, Indiana were tarred and feathered.[26]

See also[]

- Riding the rail

- Tarring and feathering in popular culture

- Tarring and feathering in the United States

References[]

- ^ Welter, Ben (2015-11-18). "Nov. 16, 1919: Tarred and feathered". StarTribune.com. Retrieved 2017-09-19.

- ^ Alam, Ehsan. "Anti-German Nativism, 1917–1919". MNopedia. Minnesota Historical Society.

- ^ "Tar and Feather. The American Heritage Dictionary of Idioms by Christine Ammer. Houghton Mifflin Company". Dictionary.reference.com. 1997-05-26. Retrieved 2012-03-07. "Tars. The Free Online Dictionary". Thefreedictionary.com. Retrieved 2012-03-07. "To criticize severely and devastatingly; excoriate." ("to excoriate" [i.e. "to flay"] being itself a similar type of metaphor).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Chisholm 1911.

- ^ Tha Avalon Project documents Accessed on 23rd June 2015

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Benjamin H. Irvin, "Tar, feathers, and the enemies of American liberties, 1768-1776." New England Quarterly (2003): 197-238. in JSTOR

- ^ Letters of Governor Francis Fauquier (1912). The William and Mary Quarterly. 21. pp. 166–67.

- ^ Young, Alfred F., 1925-2012 (1999). The shoemaker and the tea party : memory and the American Revolution. Boston, Mass.: Beacon Press. ISBN 0-8070-7140-4. OCLC 40200615.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hoock, Holger (2017). Scars of independence : America's violent birth (First ed.). New York. pp. 23–26. ISBN 978-0-8041-3728-7. OCLC 953617831.

- ^ Oliver, Peter, 1713-1791. (1961). Origin & progress of the American Rebellion; a Tory view. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. p. 157. ISBN 0-8047-0599-2. OCLC 381408.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jasanoff, Maya, 1974- (2011). Liberty's exiles : American loyalists in the revolutionary world (1st ed.). New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 21–23. ISBN 978-1-4000-4168-8. OCLC 630500155.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Levy, Barry (March 2011). "Tar and Feathers". Journal of the Historical Society. 11: 85–110. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5923.2010.00323.x – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Slaughter, Thomas P. (1986). The Whiskey Rebellion: Frontier Epilogue to the American Revolution. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195051912. pages 113-114

- ^ See Life of Joseph Smith from 1831 to 1834#Life in Kirtland, Ohio

- ^

Campbell, Thomas (1913). "John Bapst". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved December 17, 2008.

Campbell, Thomas (1913). "John Bapst". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved December 17, 2008.

- ^ Humanities, National Endowment for the (November 21, 1906). "The Abbeville press and banner. [volume] (Abbeville, S.C.) 1869-1924, November 21, 1906, Image 7" – via chroniclingamerica.loc.gov.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Harris, William J. "Etiquette, Lynching, and Racial Boundaries in Southern History: A Mississippi Example". The American Historical Review. Vol. 100, No. 2 (Apr., 1995), pp. 387–410

- ^ "Nov. 16, 1919: Tarred and feathered". StarTribune.com. Retrieved 2012-03-07.

- ^ Bills, E. R. (October 29, 2013). Texas Obscurities: Stories of the Peculiar, Exceptional and Nefarious. Father Keller: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9781625847652.

- ^ Bongiorno, Frank (2004). "Katz, Frederick Carl (1877–1960)". The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate. Melbourne University Press.

- ^ King, Terry (1983). "The Tarring and Feathering of J. K. McDougall: 'Dirty Tricks' in the 1919 Federal Election". Labour History. 45 (45): 54–67. doi:10.2307/27508605. JSTOR 27508605.

- ^ Chapman, Lee Roy (September 2011). "The Nightmare of Dreamland This Land". Retrieved September 1, 2011.

- ^ Theroux, Paul (February 13, 2011). "This was England". The Observer. London.

- ^ "Has Northern Ireland left the past behind?". 2009-11-27. Retrieved 2020-12-15.

- ^ "Belfast man tarred and feathered". London: BBC News Online. August 28, 2007. Retrieved August 28, 2007.

- ^ "Vandals left 'tar and feathers' on Confederate Mound at Crown Hill Cemetery". WRTV. 2020-06-17. Retrieved 2020-12-15.

Attribution

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Tarring and Feathering". Encyclopædia Britannica. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tarring and feathering. |

- Text of law of Richard I

- "Has anyone actually ever been tarred and feathered?" at Straight Dope

- Richard L. Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling., Alfred Knopf, 2005, ISBN 1-4000-4270-4

- Corporal punishments

- Feathers

- Vigilantism

- Vigilantism in the United States

- Physical torture techniques

- Whiskey Rebellion

- Tarring and feathering in the United States

- American frontier