The Village (2004 film)

| The Village | |

|---|---|

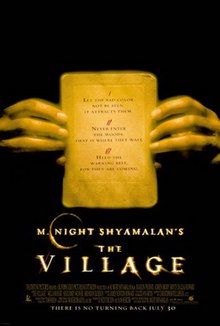

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | M. Night Shyamalan |

| Written by | M. Night Shyamalan |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Roger Deakins |

| Edited by | Christopher Tellefsen |

| Music by | James Newton Howard |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Buena Vista Pictures[1] |

Release date |

|

Running time | 108 minutes[3] |

| Country | United States[1] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $60 million[4] |

| Box office | $256.7 million[4] |

The Village is a 2004 American period thriller film[4] written, produced, and directed by M. Night Shyamalan. It stars Bryce Dallas Howard, Joaquin Phoenix, Adrien Brody, William Hurt, Sigourney Weaver, and Brendan Gleeson. The film is about a village whose population lives in fear of creatures inhabiting the woods beyond it, referred to as "Those We Don't Speak Of".

The film received mixed reviews, with many critics expressing disappointment with the twist ending.[5][6] The film gave composer James Newton Howard his fourth Oscar nomination for Best Original Score. The film was a financial success as it grossed $257 million worldwide against a $60 million production budget.[7]

Plot[]

Residents of the small, isolated, apparently 19th-century, Pennsylvania village of Covington live in fear of "Those We Don't Speak Of," nameless humanoid creatures living within the surrounding woods. The villagers have constructed a large barrier of oil lanterns and watchtowers that are constantly staffed. After the funeral of a child, the village Elders deny Lucius Hunt's request for permission to pass through the woods to get medical supplies from the towns. Later, his mother Alice scolds him for wanting to visit the towns, which the villagers describe as wicked. The Elders also appear to have secrets, keeping physical mementos hidden in black boxes, supposedly reminders of the evil and tragedy in the towns they left behind.

After Lucius makes an unsanctioned venture into the woods, the creatures leave warnings in the form of splashes of red paint on all the villagers' doors.

Ivy Elizabeth Walker, the blind daughter of Chief Elder Edward Walker, informs Lucius that she has strong feelings for him and he returns her affections. They arrange to be married, but Noah Percy, a young man with an apparent developmental disability, stabs Lucius with a knife, because he is in love with Ivy himself. Noah is locked in a room while a decision awaits regarding his fate.

Edward goes against the wishes of the other Elders, agreeing to let Ivy pass through the forest and seek medicine for Lucius. Before she leaves, Edward explains that the creatures inhabiting the woods are actually members of their own community wearing costumes and have continued the legend of monsters in an effort to frighten and deter others from attempting to leave. Ivy and two young men are sent into the forest, but they abandon Ivy almost immediately, fearful of the creatures. While traveling through the forest, one of the creatures attacks Ivy. She tricks it into falling into a deep hole to its death. The creature is actually Noah wearing one of the costumes, which he discovered under the floorboards of the room where he had been confined after stabbing Lucius.

After she climbs over the wall at the woods edge, Ivy encounters a park ranger driving a patrol car who is shocked to hear that she has come out of the woods. Ivy gives the ranger a list of medicines that she must acquire.

The ranger talks to his boss, not mentioning his encounter with Ivy, and it is revealed that it is the early 21st century instead of the 19th century. The village was founded in the late 1970s by Edward Walker, then a professor of American history at the University of Pennsylvania. Recruiting people he met at a grief counseling clinic, they join in creating a place where they would live and be protected from any aspect of the outside world. Edward's family fortune purchased a wildlife preserve, built Covington in the middle, funding a ranger corps to make sure no one got in, and even paid off the government to make it a no-fly zone.

The park ranger retrieves the requested medicine from the ranger station and Ivy returns to the village, unaware of the truth of the situation.

During her absence, the Elders secretly open their black boxes, each containing mementos from their lives in the outside world, including items related to their past traumas as crime victims. They gather around Lucius's bed when they hear that Ivy has returned and that she killed one of the monsters. Edward points out to Noah's grieving mother that his death will allow them to continue deceiving the rest of the villagers that there are creatures in the woods.

Cast[]

- Bryce Dallas Howard as Ivy Elizabeth Walker

- Joaquin Phoenix as Lucius Hunt

- Adrien Brody as Noah Percy

- William Hurt as Edward Walker

- Sigourney Weaver as Alice Hunt

- Brendan Gleeson as August Nicholson

- Cherry Jones as Mrs. Clack

- Celia Weston as Vivian Percy

- Frank Collison as Victor

- Jayne Atkinson as Tabitha Walker

- Judy Greer as Kitty Walker

- Fran Kranz as Christop Crane

- Liz Stauber as Beatrice

- Michael Pitt as Finton Coin

- Jesse Eisenberg as Jamison

- M. Night Shyamalan as Guard at Desk

- Charlie Hofheimer as Kevin Lupinski

Production[]

The film was originally titled The Woods, but the name was changed because a film in production by director Lucky McKee, The Woods (2006), already had that title.[8] Like other Shyamalan productions, this film had high levels of secrecy surrounding it, to protect the expected twist ending that was a known Shyamalan trademark. Despite that, the script was stolen over a year before the film was released, prompting many "pre-reviews" of the film on several Internet film sites[9][10] and much fan speculation about plot details. The village seen in the film was built in its entirety in one field outside Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania. An adjacent field contained an on-location temporary sound stage.[11] Production on the film started in October 2003, with delays because some scenes needing fall foliage could not be shot because of a late fall season. Principal photography was wrapped up in mid-December of that year. In April and May 2004, several of the lead actors were called back to the set. Reports noted that this seemed to have something to do with a change to the film's ending,[12][13] and, in fact, the film's final ending differs from the ending in a stolen version of the script that surfaced a year earlier; the script version ends after Ivy climbs over the wall and gets help from a truck driver, while the film version has Ivy meeting a park ranger and scenes where she returns to the village.[14]

Music[]

Soundtrack[]

| The Village | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Film score by | ||||

| Released | July 27, 2004 | |||

| Genre | Soundtrack | |||

| Length | 42:29 | |||

| Label | Hollywood | |||

| Producer | James Newton Howard | |||

| James Newton Howard chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| SoundtrackNet | |

| allmusic | |

| Filmtracks | |

The film's score was composed by James Newton Howard, and features solo violinist Hilary Hahn. The film was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Original Score, but lost to Finding Neverland.

- Track listing

- "Noah Visits"

- "What Are You Asking Me?"

- "The Bad Color"

- "Those We Don't Speak Of"

- "Will You Help Me?"

- "I Cannot See His Color"

- "Rituals"

- "The Gravel Road"

- "Race to Resting Rock"

- "The Forbidden Line"

- "The Vote"

- "It Is Not Real"

- "The Shed Not to Be Used"

Release[]

Box office[]

The film grossed $114 million in the U.S., and $142 million in international markets. Its worldwide box office totalled $256 million, the tenth highest grossing PG-13 movie of 2004.[4]

Reception[]

On Rotten Tomatoes, a review aggregator website, the film has an approval rating of 43% based on 218 reviews and an average rating of 5.39/10. The site's critics' consensus reads, "The Village is appropriately creepy, but Shyamalan's signature twist ending disappoints."[6] At Metacritic, the film holds a score of 44 out of 100 based on 40 reviews, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[5] Audiences surveyed by CinemaScore gave the film a grade "C" on scale of A+ to F.[15]

Roger Ebert gave the film one star and wrote: "The Village is a colossal miscalculation, a movie based on a premise that cannot support it, a premise so transparent it would be laughable were the movie not so deadly solemn ... To call the ending an anticlimax would be an insult not only to climaxes but to prefixes. It's a crummy secret, about one step up the ladder of narrative originality from It was all a dream. It's so witless, in fact, that when we do discover the secret, we want to rewind the film so we don't know the secret anymore."[16] Ebert named the film the tenth worst film of 2004 and subsequently put it on his "Most Hated" list.[17][18] There were also comments that the film, while raising questions about conformity in a time of "evil," did little to "confront" those themes.[19] Slate's Michael Agger commented that Shyamalan was continuing in a pattern of making "sealed-off movies that [fall] apart when exposed to outside logic."[20]

The movie had a number of admirers. Critic Jeffrey Westhoff commented that though the film had its shortcomings, these did not necessarily render it a bad movie, and that "Shyamalan's orchestration of mood and terror is as adroit as ever".[21] Philip Horne of The Daily Telegraph in a later review noted "this exquisitely crafted allegory of American soul-searching seems to have been widely misunderstood".[22]

Retrospective reviews[]

The film has attracted retrospective reviews. Emily VanDerWerff of Vox said, "[The film] may be [Shyamalan's] best film, and one of the most interesting looks at the American film industry's early attempts to incorporate the Iraq War into fictional contexts. It's been unjustly derided, and now is as good a time as any to change that." She went on to praise the twist ending, the possible connections between the plot and the Iraq War, and the technical aspects, including the cinematography.[23] Adam Chitwood of Collider praised the ending, the performances of Howard, Phoenix, and Hurt, and the cinematography. He also went on to say, "[The film] shines when it digs into themes of humanity's relationship with sorrow, and whether pain and violence can be excised from our lives or if we're destined to fall prey to harmful sins. Devoid of expectations, [the film] holds up far better than you may remember."[24] Chris Evangelista of SlashFilm called it, "one of Shyamalan's most interesting films, and perhaps one of his best. A melancholy meditation on grief and fear, [because] it radiates sorrow in ways his other films do not. Yes, it does have that expected Shyamalan twist – two of them, in fact. But the film is more than its twists, and deserves to be watched with fresh eyes."[25] Kayleigh Donaldson of Syfy Wire praised the cinematography, and said, "...[the film] stands as one of the strongest representations of Shyamalan’s ethos, for better or worse."[26] Carlos Morales of IGN argued that the film was misunderstood at the time of its release because it was mismarketed as a horror film, and also because of audience expectations that had been built up by Shyamalan's three previous films. "The real twist was that the movie they wanted wasn't the one Shyamalan made."[27]

Accolades[]

- 2005 ASCAP Film and Television Music Awards

- Won – Top Box Office Film — James Newton Howard

- 2004 Academy Awards (Oscars)

- Nominated – Best Original Score — James Newton Howard

- 2005 10th Empire Awards

- Nominated – Best Actress — Bryce Dallas Howard

- Nominated – Best Newcomer — Bryce Dallas Howard

- Nominated – Best Director — M. Night Shyamalan

- Won – Best Technical/Artistic Achievement — Roger Deakins

- 2005 MTV Movie Awards

- Nominated – Best Breakthrough Female Performance — Bryce Dallas Howard

- 2005 Motion Picture Sound Editors (Golden Reel Award)

- Nominated – Best Sound Editing in a Feature: Music, Feature Film — Thomas S. Drescher

- 2004 Online Film Critics Society Awards

- Nominated – Best Breakthrough Performance — Bryce Dallas Howard

- 2005 Teen Choice Awards

- Nominated – Choice Movie Scary Scene — Bryce Dallas Howard, Ivy Walker waits at the door for Lucius Hunt.

- Nominated – Choice Movie: Thriller

Other honors[]

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2005: AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores – Nominated[28]

The soundtrack was widely praised, and was nominated by the American Film Institute as one of the Best Film Scores[29] and the Academy Award for Best Original Score.

Plagiarism allegation[]

Simon & Schuster, publishers of the 1995 young adult book Running Out of Time by Margaret Peterson Haddix, claimed that the film had taken ideas from the book.[30] The plot of Shyamalan's movie had several similarities to the book. They both involve a 19th-century village, which is actually a park in the present day, have young heroines on a search for medical supplies, and both have adult leaders bent on keeping the children in their village from discovering the truth.[31]

No lawsuit was ever filed over the similarity.[32]

Home media[]

The film was released on VHS and DVD on January 11, 2005. This is currently the only M. Night Shyamalan film that does not have a Blu-ray version. The Village was also the last Shyamalan film to be released on VHS.

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "The Village (2004)". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved September 14, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Village (2004)- Financial Information". The Numbers. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ^ "The Village (12A)". British Board of Film Classification. July 26, 2004. Retrieved August 1, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "The Village (2004)". Box Office Mojo.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Village Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Village (2004)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/24/movies/shyamalan-tom-cruise.html

- ^ Scott W. Davis, Movie Reviews > The Village, HorrorExpress.com

- ^ "Pre-review of The Village". Webcitation.org. Archived from the original on October 26, 2009. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "Pre-review of The Village at". Horrorlair.com. February 18, 2007. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ IMdb.com – FAQ for The Village "Where exactly was the movie filmed? Did they use historical buildings or did they build everything?"

- ^ "Change to ending of The Village". Comingsoon.net. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "More views of The Village – aerial". Webcitation.org. Archived from the original on August 20, 2009. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "The Village Script – Dialogue Transcript". Script-o-rama.com. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "Cinemascore". Archived from the original on December 20, 2018. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (July 19, 2004). "The Village movie review & film summary (2004)". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ "Top 10 Worst Movies of the 2000's - Roger Ebert Review". Retrieved November 15, 2020.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (August 11, 2005). "Ebert's Most Hated". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ "The Reel Deal: The Village". Oregonherald.com. March 16, 2012. Archived from the original on January 6, 2014. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ Yglesias, Matthew. "Village Idiot". Slate.com. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ Northwest Herald's The Village review

- ^ "telegraph.co.uk". telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved March 12, 2013.[dead link]

- ^ VanDerWerff, Emily (January 23, 2019). "M. Night Shyamalan's The Village is an underrated masterpiece". Vox. Retrieved September 2, 2019.

- ^ Chitwood, Adam. "In Defense of M. Night Shyamalan's 'The Village'". Collider. Retrieved September 2, 2019.

- ^ Evangelista, Chris (August 1, 2017). "The Unpopular Opinion: 13 Years Later, 'The Village' Stands as One of M. Night Shyamalan's Best Movies". SlashFilm. Retrieved September 2, 2019.

- ^ Donaldson, Kayleigh (July 30, 2019). "M. NIGHT SHYAMALAN'S THE VILLAGE IS A MASTERPIECE AND YOU CAN'T CONVINCE ME OTHERWISE". Syfy Wire. Retrieved September 2, 2019.

- ^ Morales, Carlos (August 17, 2019). "The Village: M Night Shyamalan's misunderstood love story". IGN. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved August 6, 2016.

- ^ "HollywoodBowlBallot" (PDF). Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "Stolen idea in The Village?". Film.guardian.co.uk. August 10, 2004. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "Stolen idea in The Village?". Film.guardian.co.uk. August 10, 2004. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ Kamberg, Mary-Lane (December 15, 2013). Margaret Peterson Haddix. Rosen Publishing Group. pp. 41–42. ISBN 9781477717721. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Village (film). |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Village |

- The Village at IMDb

- The Village at AllMovie

- The Village at Rotten Tomatoes

- American Cinematographer Magazine, August 2004. Interview with Roger Deakins on The Village's cinematography.

- "Disney and Shyamalan in your back yard" – Website by a local resident describing the filming of The Village in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania.

- The Woods unspecified draft script for The Village

- 2004 films

- English-language films

- American films

- American thriller films

- Films about blind people

- Films involved in plagiarism controversies

- Films set in Pennsylvania

- Films set in the 19th century

- Films set in the 21st century

- Films shot in Delaware

- Films shot in New Jersey

- Films shot in Pennsylvania

- Touchstone Pictures films

- Films with screenplays by M. Night Shyamalan

- Films directed by M. Night Shyamalan

- Films produced by M. Night Shyamalan

- Films produced by Sam Mercer

- Films produced by Scott Rudin

- Films scored by James Newton Howard