Toki Pona

| Toki Pona | |

|---|---|

| toki pona | |

| |

| Pronunciation | [ˈtoki ˈpona] |

| Created by | Sonja Lang |

| Date | 2001 |

| Setting and usage | Testing principles of minimalism, the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis and pidgins |

| Purpose | Constructed language, combining elements of the subgenres personal language and philosophical language |

| Latin script; sitelen pona (logographic); sitelen sitelen (logographic with an alphasyllabary for foreign words); and numerous other unofficial scripts | |

| luka pona, toki pona luka | |

| Sources | A posteriori language, with elements of English, Tok Pisin, Finnish, Georgian, Dutch, Acadian French, Esperanto, Croatian and Chinese |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | None (mis) |

| Glottolog | None |

| IETF | art-x-tokipona |

Toki Pona (rendered as toki pona,[a] literally "good language", "simple language" or "the language of good"; IPA: [ˈtoki ˈpona] (![]() listen); English: /ˈtoʊki ˈpoʊnə/) is a philosophical artistic constructed language (or philosophical artlang) known for its small vocabulary, simplicity and ease of acquisition.[3] It was created by Canadian linguist and translator Sonja Lang[3] for the purpose of simplifying thoughts and communication and was first published online in 2001 as a draft,[1] and in a more complete form in the book Toki Pona: The Language of Good in 2014.[4][5] In July 2021, Lang released a supplementary dictionary, based on community usage, called the Toki Pona Dictionary. A small community of speakers developed in the early 2000s.[6][7] While activity mostly takes place online in chat rooms, on social media, and in other groups, there were a few organized in-person meetings during the 2000s[1] and 2010s.

listen); English: /ˈtoʊki ˈpoʊnə/) is a philosophical artistic constructed language (or philosophical artlang) known for its small vocabulary, simplicity and ease of acquisition.[3] It was created by Canadian linguist and translator Sonja Lang[3] for the purpose of simplifying thoughts and communication and was first published online in 2001 as a draft,[1] and in a more complete form in the book Toki Pona: The Language of Good in 2014.[4][5] In July 2021, Lang released a supplementary dictionary, based on community usage, called the Toki Pona Dictionary. A small community of speakers developed in the early 2000s.[6][7] While activity mostly takes place online in chat rooms, on social media, and in other groups, there were a few organized in-person meetings during the 2000s[1] and 2010s.

The underlying feature of Toki Pona is minimalism. It focuses on simple, near-universal concepts, making use of very little to express the most. The language is isolating with 14 phonemes and has around 120 to 137 "essential" root words, as well as a number of less-used words (see Vocabulary).[b] Its words are easy to pronounce across languages, but it was not created to be an international auxiliary language. Inspired by Taoist philosophy, the language is designed to help users concentrate on basic things and to promote positive thinking, in accordance with the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis. Despite the small vocabulary, speakers are able to understand and communicate with each other, mainly relying on context and combinations of words to express more specific meanings.

Etymology[]

The name of the language is constituted by toki (language),[11] derived from Tok Pisin tok, which itself comes from English "talk"; and pona (good/simple), from Esperanto bona (good),[11] from Latin bonus. The name toki pona therefore means both "good language" and "simple language" emphasising that the language encourages speakers to find joy in simplicity.

Purpose[]

Sonja Lang (née Sonja Elen Kisa) started developing Toki Pona as a way of simplifying her thoughts during depression.[6][12]

One of the language's main goals is a focus on minimalism. It is designed to express maximal meaning with minimal complexity.[2] Like a pidgin, it focuses on simple concepts and elements that are near-universal among cultures. It has a minimal vocabulary and 14 phonemes devised to be easy to pronounce for speakers of various language backgrounds.[3][1][6]

Inspired by Taoist philosophy, another goal of Toki Pona is to help its speakers focus on the essentials by reducing complex concepts into basic elements and remove complexity from the thought process.[3][13] From these simple notions, more complex ideas can be created by simple combining.[2] This allows the users to see the fundamental nature and effect of the ideas expressed.

In accordance with the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis, which states that a language changes the way its speakers think and behave,[6][13] Toki Pona tries to induce positive thinking.[14]

Another aim of the language is for the speakers to become aware of the present moment and pay more attention to the surroundings and the words people use.[3] According to its author, it is meant to be "fun and cute".[15]

Although it was not intended as an international auxiliary language,[14] people from all around the world use it for communication.[3]

History[]

An early version of the language was published online in 2001 by Sonja Lang, and it quickly gained popularity.[6] Early activity took place in a Yahoo! group. Members of the group discussed the language with one another in English, Toki Pona, and Esperanto, proposed changes, and talked about the resources on the tokipona.org site. At its peak member count, the group had a little over 500 members. Messages in the group were archived in the Toki Pona forum using phpBB.

Lang later released her first book on the language, Toki Pona: The Language of Good, in 2014 which features 120 words plus 3 synonyms and provides a completed form of the language based on how Lang used the language at the time.[4] In 2016, the book was also published in French.[16]

In 2008 an application for an ISO 639-3 code was rejected, with a statement that the language was too young.[17] Another request was rejected in 2018 as the language "does not appear to be used in a variety of domains nor for communication within a community which includes all ages".[18]

Toki Pona was the subject of some scientific works,[1] and it has also been used for artificial intelligence and software tools,[16] as well as a therapeutic method for eliminating negative thinking by having patients keep track of their thoughts in the language.[6] In 2010 it was chosen for the first version of the vocabulary for the ROILA project. The purpose of the study was to investigate the use of an artificial language on the accuracy of machine speech recognition, and it was revealed that the modified vocabulary of Toki Pona significantly outperformed English.[19]

In 2021, Lang released her second book, Toki Pona Dictionary, a comprehensive two-way Toki Pona–English dictionary including more than 11,000 entries detailing the use of the language as she gathered from polls conducted in the ma pona pi toki pona Discord server over a few months. The book presents the original 120 words plus 16 nimi ku suli (major dictionary words) as gathered from at least over 40% of respondents. It also contains words given by 40% or less of respondents called nimi ku pi suli ala (minor dictionary words).

Phonology and phonotactics[]

Inventory[]

Toki Pona has nine consonants (/p, t, k, s, m, n, l, j, w/) and five vowels (/a, e, i, o, u/),[1][6] shown here with the International Phonetic Alphabet symbols. Stress falls on the initial syllable of a word, and it is marked by an increase in loudness, length, and pitch.[20] There are no diphthongs, contrasting vowel length, consonant clusters (except those starting with the nasal coda), or tones.[1] Both its sound inventory and phonotactics are compatible with the majority of human languages, and are therefore readily accessible.[4]

| Labial | Coronal | Dorsal | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | |

| Stop | p | t | k |

| Fricative | s | ||

| Approximant | w | l | j |

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u |

| Mid | e | o |

| Open | a | |

Distribution[]

The statistical vowel spread is fairly typical when compared with other languages.[1] Counting each root once, 32% of vowels are /a/, 25% are /i/, with /e/ and /o/ a bit over 15% each, and 10% are /u/.[1] The usage frequency in a 10kB sample of texts was slightly more skewed: 34% /a/, 30% /i/, 15% each /e/ and /o/, and 6% /u/.[21]

Of the syllable-initial consonants, /l/ is the most common, at 20% total; /k, s, p/ are over 10%, then the nasals /m, n/ (not counting final N), with the least common, at little more than 5% each, being /t, w, j/. The high frequency of /l/ and low frequency of /t/ is somewhat unusual among the world's languages.[1]

Syllable structure[]

Syllables are of the form (C)V(N), i.e. optional consonant + vowel + optional final nasal, or V, CV, VN, CVN. The consonant is obligatory in syllables that are not word-initial.[16] As in most languages, CV is the most common syllable type, at 75% (counting each root once). V and CVN syllables are each around 10%, while only 5 words have VN syllables (for 2% of syllables).[1]

Most roots (70%) are disyllabic; about 20% are monosyllables and 10% trisyllables. This is a common distribution, and similar to Polynesian.[1]

Phonotactics[]

The following sequences are not allowed: */ji, wu, wo, ti/, nor may a syllable's final nasal occur before /m/ or /n/ in the same root.[1][16]

Proper nouns are usually converted into Toki Pona proper adjectives using a set of guidelines. The native, or even colloquial, pronunciation is used as the basis for the subsequent sound conversion. Thus, England or English become Inli and John becomes San.[22]

Allophony[]

The nasal at the end of a syllable can be pronounced as any nasal stop, though it is normally assimilated to the following consonant. That is, it typically occurs as an [n] before /t/, /s/ or /l/, as an [m] before /p/ or /w/, as an [ŋ] before /k/, and as an [ɲ] before /j/.[1]

Because of its small phoneme inventory, Toki Pona allows for extensive allophonic variation. For example, /p t k/ may be pronounced [b d ɡ] as well as [p t k], /s/ as [z] or [ʃ] as well as [s], /l/ as [ɾ] as well as [l], and vowels may be either long or short.[1]

Writing systems[]

14 Latin letters, a e i j k l m n o p s t u w, are used to write the language. They have the same values as in the International Phonetic Alphabet:[1] j sounds like English y (as in many Germanic and Slavic languages) and the vowels are like those of Spanish, Modern Greek, or Modern Hebrew. Capital initials are used to mark proper adjectives, while Toki Pona roots are always written with lowercase letters, even when they start a sentence.[1][2]

Besides the Latin alphabet, which is the most common way of writing the language, many alternative writing systems have been developed for and adapted to Toki Pona.[1] Most successful and widespread are two logographic writing systems, sitelen pona and sitelen sitelen. Both were included in the book Toki Pona: The Language of Good.

sitelen pona[]

The sitelen pona writing system was devised as an alternative writing system by Lang herself, and first published in her book Toki Pona: The Language of Good in 2014.[5] In it each word is represented by its own symbol. It has been described as "a hieroglyphic-like script that makes use of squiggles and other childlike shapes"[23] . Proper names are written inside a cartouche-like symbol using a series of symbols, where each symbol represents the first letter of its word. Symbols representing a single adjective may be written inside or above the symbol for the preceding word that they modify. The symbol of the language ![]() is written in sitelen pona,[23] with the symbol

is written in sitelen pona,[23] with the symbol ![]() (pona) written inside the symbol

(pona) written inside the symbol ![]() (toki).

(toki).

As of 2021 sitelen pona is widely used in the Toki Pona community. In a 2021 census of about 800 people in the Toki Pona community, 61% of respondents reported knowing sitelen pona, and 43% reported using it. Among the roughly 90 people who responded to the survey in Toki Pona (who are more likely to be advanced or fluent speakers), 81% reported knowing the writing system, 59% reported using it, and 28% claimed it was a preferred writing system to them.[24]

In August 2021 sitelen pona was proposed for inclusion on the Under-ConScript Unicode Registry for allocation in the U+F1900..U+F1AFF location.[25][26]

sitelen sitelen[]

The sitelen sitelen writing system, also known as sitelen suwi,[27] was created by Jonathan Gabel. This more elaborate non-linear system uses two separate methods to form words: logograms representing words and an alphasyllabary for writing the syllables (especially for proper names). The complexity of the glyphs along with their artful designs are chosen to help people who use this writing system to slow down and explore how not only the language but also the method of communication can influence their thinking.[5][27]

sitelen sitelen takes visual inspiration from US west-coast comix artists such as Jim Woodring and US east-coast graffiti artists such as Kenny Scharf, and uses logographic principals present in other writing systems including Egyptian hieroglyphs, Chinese characters, Maya script,[28] Miꞌkmaw hieroglyphic writing, Dongba symbols, as well as early Pagan and Christian signs and symbols.[29]

As of 2021 only a minority of the Toki Pona community actively uses sitelen sitelen. In a 2021 census of about 800 people in the Toki Pona community, 31% of respondents reported knowing it, and 11% reported using it.[24]

Grammar[]

Toki Pona's word order is subject–verb–object.[13][30] The word li introduces predicates, e introduces direct objects, prepositional phrases follow the objects, and la phrases come before the subject to add additional context.[16]

Some roots are grammatical particles, while others have lexical meanings. The lexical roots do not fall into well defined parts of speech; rather, they may be used generally as nouns, verbs, modifiers, or interjections depending on context or their position in a phrase. For example, ona li moku may mean "they ate" or "it is food".[1][13]

Sentence structures[]

A sentence may be an interjection, statement, wish/command, or question.

For example, interjections such as a, ala, ike, jaki, mu, o, pakala, pona, toki, etc. can stand alone as a sentence.[13]

Statements follow the normal structure of subject-predicate with an optional la phrase at the beginning. The word li always precedes the predicate unless the subject is a mi or sina. The direct object marker e comes before direct objects. More li and e markers can present new predicates or direct objects. Vocative phrases come before the main sentence and are marked with o at the end of the phrase, after the addressee.[13][16]

In commands, the word o comes before a verb to express a second person command. It can also replace li, or come after the subjects mi or sina, to express wishes.

There are two ways to form yes-no questions in Toki Pona. The first method is to use the "verb ala verb" construction in which ala comes in between a duplicated verb, auxiliary verb, or other predicators.[13] Another way to form a yes-no question is to put anu seme? (lit. 'or what?') at the end of a sentence. Questions cannot be made by just putting a question mark at the end of a sentence.

Non-polar questions are formed by replacing the unknown information with the interrogative word seme.[16]

Pronouns[]

Toki Pona has basic pronouns: mi (first person), sina (second person), and ona (third person).[31]

The pronouns do not specify number or gender. Therefore, ona can mean "he", "she", "it", or "they".

Whenever the subject of a sentence is either of the unmodified pronouns mi or sina, then li is not used to separate the subject and predicate.[16]

Nouns[]

With such a small root-word vocabulary, Toki Pona relies heavily on noun phrases, where a noun is modified by a following root, to make more complex meanings.[12] A typical example is combining jan (person) with utala (fight) to make jan utala (soldier, warrior).

Nouns do not decline according to number. jan can mean "person", "people", "humanity", or "somebody", depending on context.[1]

Toki Pona does not use isolated proper nouns; instead, they must modify a preceding noun. For this reason, they may be called "proper adjectives" or simply “proper words” instead of “proper nouns”. For example, names of people and places are used as modifiers of the common roots for "person" and "place", e.g. ma Kanata (lit. 'Canada country') or jan Lisa (lit. 'Lisa person').[1]

Modifiers[]

Phrases in Toki Pona are head-initial; modifiers always come after the word that they modify.[13] Therefore, soweli utala, lit. 'animal of fighting', can be a "fighting animal", whereas utala soweli, lit. 'fighting of animal', can mean "animal war".[1]

When a second modifier is added to a phrase, for example jan pona lukin, it modifies all that comes before it, so ((jan pona) lukin) can be "friend watching", rather than (jan (pona lukin)), which can be "person good-looking".[1]

The particle pi is placed after the head and before the modifiers, to group the modifiers into another phrase that functions as a unit to modify the head, so jan pi pona lukin can be (jan pi (pona lukin)), "good-looking person". In this case, lukin modifies pona and pona lukin as a whole modifies jan.[1][16]

Demonstratives, numerals, and possessive pronouns come after the head like other modifiers.[1]

Verbs[]

Toki Pona does not inflect verbs according to person, tense, mood, or voice, as the language features no inflection whatsoever. Person is indicated by the subject of the verb; time is indicated through context or by a temporal adverb in the sentence.[1]

Prepositions are used in the predicate in place of a regular verb.[5][30]

Vocabulary[]

Toki Pona has around 120 to 137[b] root words depending on the speaker.[24] Each is polysemous and covers a range of similar concepts,[28] so suli not only means "big" or "long", but also "important".[1] Their use relies heavily on context. To express more complex thoughts, the roots can be combined. For example, jan pona can mean "friend", although it translates to lit. 'good/friendly person',[12] and telo nasa, lit. 'strange water' or 'liquid of craziness', would be understood to mean "alcohol" or "alcoholic beverage" depending on the context. The verb "to teach" can be expressed by pana e sona, lit. 'give knowledge'.[1] Essentially identical concepts can be described by different words as the choice relies on the speaker's perception and experience.[4]

Colors[]

Toki Pona has five root words for colors: pimeja (black), walo (white), loje (red), jelo (yellow), and laso (grue).[3][1] Although the simplified conceptualization of colors tends to exclude a number of colors that are commonly expressed in Western languages, speakers sometimes may combine these five words to make more specific descriptions of certain colors. For instance, "purple" may be represented by combining laso and loje. The phrase laso loje means "a reddish shade of blue" and loje laso means "a bluish shade of red".[1]

Numbers[]

Toki Pona has root words for one (wan), two (tu), and many (mute). In addition, ala can mean "zero", although its meaning is lit. 'no' or 'none', and ale "all" can express an infinite or immense amount.

The simplest number system uses these five roots to express any amount necessary. For numbers larger than two, speakers would use mute which means "many".[28]

A more complex system expresses larger numbers additively by using phrases such as tu wan for three, tu tu for four, and so on. This feature purposely makes it impractical to communicate large numbers.[28][32]

An alternate system for larger numbers, described in Lang's book, uses luka (lit. 'hand') to signify "five", mute (lit. 'many') to signify "twenty" and ale (lit. 'all') to signify "hundred". For example, using this structure ale tu would mean "102" and mute mute mute luka luka luka tu wan would signify "78".[33]

Roots history[]

Some words have obsolete synonyms. For example, nena replaced kapa (protuberance) early in the language's development for unknown reasons.[34] Later, the pronoun ona replaced iki (he, she, it, they), which was sometimes confused with ike (bad).[32]

Similarly, ali was added as an alternative to ale (all) to avoid confusion with ala (no, not) among people who reduce unstressed vowels, though both forms are still used.

Originally, oko meant "eye" and lukin was used as a verb "see". In the book, the meanings were later merged into lukin, oko being the alternative.[5][16]

Words that have been simply removed from the lexicon include leko (block, stairs), monsuta (monster, fear), majuna (old), kipisi (to cut), and pata (sibling).[34] These words are now considered outdated because they were not included in the official book.[34]

Besides nena and ona, which replaced existing roots, a few roots were added to the original 118: pan (grain, bread, pasta, rice), esun (market, shop, trade), alasa (hunt, gather), and namako (extra, additional, spice), another word for sin (new).[35]

Provenance[]

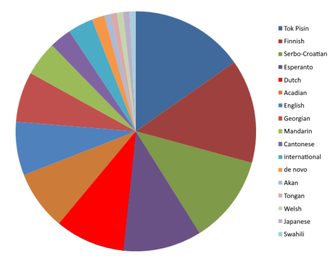

Most Toki Pona roots come from English, Tok Pisin, Finnish, Georgian, Dutch, Acadian French, Esperanto, Croatian, with a few from Chinese (Mandarin and Cantonese).[11][2]

Many of these derivations are transparent. For example, toki (speech, language) is similar to Tok Pisin tok and its English source "talk", while pona (good, positive), from Esperanto bona, reflects generic Romance bon, buona, English "bonus", etc. However, the changes in pronunciation required by the simple phonetic system often make the origins of other words more difficult to see. The word lape (to sleep, to rest), for example, comes from Dutch slapen and is cognate with English "sleep"; kepeken (to use) is somewhat distorted from Dutch gebruiken, and akesi from hagedis (lizard) is scarcely recognizable. [Because *ti is an illegal syllable in Toki Pona, Dutch di becomes si.][11]

Although only 14 roots (12%) are listed as derived from English, a large number of the Tok Pisin, Esperanto, and other roots are transparently cognate with English, raising the English-friendly portion of the vocabulary to about 30%. The portions of the lexicon from other languages are 15% Tok Pisin, 14% Finnish, 14% Esperanto, 12% Croatian, 10% Acadian French, 9% Dutch, 8% Georgian, 5% Mandarin, 3% Cantonese; one root each from Welsh, Tongan (an English borrowing), Akan, and an uncertain language (apparently Swahili); four phonesthetic roots (two which are found in English, one from Japanese, and one which was made up); and one other made-up root (the grammatical particle e).[11]

Signed Toki Pona and Luka Pona[]

Signed Toki Pona, or toki pona luka, is a manually coded form of Toki Pona. Each word and letter has its own sign, which is distinguished by the hand shape, location of the hand on the body, palm or finger orientation, and the usage of one or both hands. Most signs are performed with the right hand at the required location. A few signs, however, are performed with both hands in a symmetrical way. To form a sentence, each of the signs is performed using the grammar and word order of Toki Pona.[5]

A more naturalistic constructed sign language called luka pona also exists, and is more widely used in the Toki Pona community than toki pona luka. It is a separate language with its own grammar, but has a vocabulary that generally parallels Toki Pona. luka pona's signs have increased iconicity as compared to toki pona luka, and many signs are loan-words from natural sign languages. Its grammar is subject-object-verb, and, like natural sign languages, it makes use of classifier constructions and signing space.[36][37] In Toki Pona Dictionary, Sonja Lang recommends learning luka pona instead of toki pona luka.[38]

Community[]

The language is fairly well known among Esperantists, who often offer courses and conversation groups at their meetings.[1] In 2007, Lang reportedly said that at least 100 people speak Toki Pona fluently and estimated that a few hundred have a basic knowledge of the language.[6][39] One-hour courses of Toki Pona were taught on various occasions by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology during their Independent Activities Period.[6]

The language is used mainly online on social media, in forums, and other groups.[39] Users of the language are spread out across multiple platforms. A Yahoo! group existed from about 2002 to 2009, when it moved to a forum on a phpBB site.[40][41] For a short time there was a Wikipedia written in Toki Pona (called lipu Wikipesija). It was closed in 2005[42] and moved to Wikia/Fandom, and then moved from Fandom to an independent website on 23 April 2021.[43]

The largest groups exist on Reddit and Facebook. Two large groups exist on Facebook—one designated for conversation in Toki Pona and English, and the other for conversation in only Toki Pona.[44] The most subscribed group, in which members communicate in both English and Toki Pona, has over 5,000 total members as of September 2021.[45] The largest community on Reddit has over 7,000 members.[46] The largest Discord group has over 4,500 members as of September 2021.[47]

An online census was conducted in 2021. Around 1000 people worldwide filled it. Of them, 165 claimed to be advanced or fluent speakers and more than 650 reported to know Toki Pona.[24]

As of 30 November 2021, the language has been added to the popular video game Minecraft.[48]

Culture[]

There are some published books in Toki Pona. Most of them are language-learning books for beginners like meli olin moli.[49] Since the publication of the first books in Toki Pona (2020) some people made a registered zine in Toki Pona. It is called lipu tenpo (lit. book of time) and is officially registered as a zine in the United Kingdom.[50]

Sample texts[]

mama pi mi mute[1][2] (The Lord's Prayer, translated by Bryant J. Knight, 2005)

mama pi mi mute o, sina lon sewi kon.

nimi sina li sewi.

ma sina o kama.

jan o pali e wile sina lon sewi kon en lon ma.

o pana e moku pi tenpo suno ni tawa mi mute.

o weka e pali ike mi. sama la mi weka e pali ike pi jan ante.

o lawa ala e mi tawa ike.

o lawa e mi tan ike.

tenpo ali la sina jo e ma e wawa e pona.

Amen.

jan Meli o[52] (Ave Maria, translated by Tobias Merkle, 2020)

jan Meli o,

kon sewi li suli insa sina.

wan sewi li poka sina.

lon meli la, wan sewi li pona e sina.

kili pona pi insa sina li sewi Jesu.

jan Meli sewi o!

mama pi jan sewi o!

tenpo ni la, tenpo pi moli mi mute la,

o toki tawa wan sewi tan mi mute jan ike.

awen.

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights[53]

jan ali li kama lon nasin ni: ona li ken tawa li ken pali. jan ali li kama lon sama. jan ali li jo e ken pi pilin suli. jan ali li ken pali e wile pona ona. jan ali li jo e ken pi sona pona e ken pi pali pona. jan ali li wile pali nasin ni: ona li jan pona pi ante.

ma tomo Pape[54] (The Tower of Babel story, translated by Bryant J. Knight, 2005)

jan ali li kepeken e toki sama.

jan li kama tan nasin pi kama suno li kama tawa ma Sinale li awen lon ni.

jan li toki e ni: "o kama! mi mute o pali e kiwen. o seli e ona".

jan mute li toki e ni: "o kama! mi mute o pali e tomo mute e tomo palisa suli. sewi pi tomo palisa li lon sewi kon. nimi pi mi mute o kama suli! mi wile ala e ni: mi mute li lon ma ante mute".

jan sewi Jawe li kama anpa li lukin e ma tomo e tomo palisa.

jan sewi Jawe li toki e ni: "jan li lon ma wan li kepeken e toki sama li pali e tomo palisa. tenpo ni la ona li ken pali e ijo ike mute. mi wile tawa anpa li wile pakala e toki pi jan mute ni. mi wile e ni: jan li sona ala e toki pi jan ante".

jan sewi Jawe li kama e ni: jan li lon ma mute li ken ala pali e tomo.

nimi pi ma tomo ni li Pape tan ni: jan sewi Jawe li pakala e toki pi jan ali. jan sewi Jawe li tawa e jan tawa ma mute tan ma tomo Pape.

|

wan taso (2003)[55]

|

Alone (translation of wan taso)

|

See also[]

Notes[]

- ^ When writing in Toki Pona, capital letters are used only for proper names, such as the names of people.[1][2]

- ^ a b Prior to the publication of Toki Pona: The Language of Good, the language grew to 118 words.[8] Between then and the publication of Toki Pona Dictionary, varying counts were given for the number of words in the former (nimi pu), ranging between 120 and 125.[3][1][6] The Toki Pona Dictionary added 16 new "essential" words (nimi ku suli, major dictionary words),[9] and states on its back cover that there are a total of 137.[10] It also includes a number of nimi ku pi suli ala ("minor dictionary words").[9]

References[]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag Blahuš, Marek (November 2011). Fiedler, Sabine (ed.). "Toki Pona: eine minimalistische Plansprache" [Toki Pona: A Minimalistic Planned Language] (PDF). Interlinguistische Informationen (in German). Berlin. 18: 51–55. ISSN 1432-3567.

- ^ a b c d e f Rogers, Steven D. (2011). "Part I: Made-Up Languages – Toki pona". A Dictionary of Made-Up Languages. United States of America: Adams Media. ISBN 978-1440528170.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Morin, Roc (2015-07-15). "How to Say (Almost) Everything in a Hundred-Word Language". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2019-08-01.

- ^ a b c d Thomas, Simon (2018-03-27). "Exploring Toki Pona: do we need more than 120 words?". Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 2019-05-11. Retrieved 2019-02-03.

- ^ a b c d e f Lang (2014:134).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Roberts, Siobhan (2007-07-09). "Canadian has people talking about lingo she created". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2017-03-10.

- ^ Јовановић, Тијана (Tijana Jovanović) (2006-12-15). "Вештачки језици (Veštački jezici)" [Artificial languages]. Политикин Забавник (Politikin Zabavnik) (in Serbian) (2862). Archived from the original on 2007-06-10.

- ^ "Classic Word List (Improved!)". tokipona.net. Retrieved 2019-01-07.

- ^ a b Lang (2021:22–23).

- ^ Lang (2021:back cover).

- ^ a b c d e "Toki Pona word origins". tokipona.org. 2009-09-28. Archived from the original on 2010-03-08.

- ^ a b c Dance, Amber (2007-08-24). "In their own words – literally / Babel's modern architects". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2013-01-03. Retrieved 2007-08-29.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Tomaszewski, Zach (2012-12-11). "A Formal Grammar for Toki Pona" (PDF). University of Hawai‘i. Retrieved 2019-09-21.

- ^ a b Malmkjær, Kirsten (2010). "Artificial languages". The Routledge Linguistics Encyclopedia (3rd ed.). New York: Routledge. p. 34. ISBN 9780415424325. OCLC 656296619.

- ^ Okrent, Arika (2009). "The Klingons, the Conlangers, and the Art of Language – 26. The Secret Vice". In the Land of Invented Languages. New York: Spiegel & Grau. ISBN 978-0-385-52788-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Fabbri, Renato (July 2018). "Basic concepts and tools for the Toki Pona minimal and constructed language". ACM Transactions on Asian and Low-Resource Language Information Processing. arXiv:1712.09359.

- ^ "Change Request Documentation: 2007-011". iso639-3.sil.org. 2020. Retrieved 2020-06-05.

- ^ "Change Request Documentation: 2017-035". SIL ISO 639-3. Retrieved 2019-01-10.

- ^ Mubin, Omar; Bartneck, Christoph; Feijs, Loe (2010). "Towards the Design and Evaluation of ROILA: A Speech Recognition Friendly Artificial Language". Advances in Natural Language Processing. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. LNCS 6233/2010: 250–256. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.175.6679. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-14770-8_28. ISBN 978-3-642-14769-2 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Lang (2014:16).

- ^ "Phoneme frequency table / Ofteco de fonemoj". lipu pi toki pona pi jan Jakopo. Archived from the original on 2007-11-14.

- ^ Lang, Sonja. Knight, Bryant (ed.). "Phonetic conversion of proper names". lipu pi jan Pije. Archived from the original on 2020-02-17. Retrieved 2019-01-15.

- ^ a b "Toki Pona – The language of good". Smith Journal. Melbourne, Australia. 2019-06-03. Retrieved 2019-10-20.

- ^ a b c d "Toki Pona Census". 2021-03-05. Retrieved 2021-03-06.

- ^ Bettencourt, Rebecca G. (2021-08-06). "Under-ConScript Unicode Registry". KreativeKorp. Retrieved 2021-10-23.

- ^ Bettencourt, Rebecca G. (2021-08-06). "Sitelen Pona: U+F1900 - U+F1AFF". KreativeKorp. Retrieved 2021-10-23.

- ^ a b Gabel, Jonathan (2019-10-20). "Lesson 1: Welcome". Jonathan Gabel. Retrieved 2019-10-20.

- ^ a b c d Синящик, Анна (Anna Sinyashchik) (2018-01-03). "Коротко и ясно. Как искусственный язык учит фокусироваться на главном" [Briefly and Clearly. How an Artificial Language Teaches to Focus on What's Important]. Фокус (Focus) (in Russian).

- ^ Gabel, Jonathan (2021). "sitelen sitelen acknowlegements and etymology". Jonathan Gabel. Retrieved 2021-10-22.

- ^ a b "3. Toki Pona Text – Grammar and Vocabulary". Language Creation Society. Retrieved 2019-01-25.

- ^ Martin, Matthew (2007-09-11). "Toki Pona: Pronouns unleashed". My Suburban Destiny. Retrieved 2019-01-25.

- ^ a b Yerrick, Damian (2002-10-23). "Toki Pona li pona ala pona? A review of Sonja Kisa's constructed language Toki Pona". Pin Eight. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- ^ "Numbers". tokipona.net. Retrieved 2019-01-26.

- ^ a b c Knight, Bryant (2017-08-31). "Extinct words". lipu pi jan Pije. Archived from the original on 2020-02-17. Retrieved 2019-01-13.

- ^ "Classic Word List (Improved!)". tokipona.net. Retrieved 2019-01-07.

- ^ "luka pona". lukapona.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2021-07-03.

- ^ "lipu tenpo nanpa akesi > lipu tenpo". lipu tenpo. 2021-02-01. Retrieved 2021-07-03.

- ^ Lang (2021:11).

- ^ a b Marsh, Stefanie (2007-09-06). "Now you're really speaking my language". The Times. London, England. p. 2.

- ^ Martin, Matthew (2018-03-11). "Conlang SE". Fake languages by a fake linguist. Retrieved 2019-10-20.

- ^ "tokipona Toki Pona". Yahoo! Groups. 2019-10-20. Archived from the original on 2013-04-30. Retrieved 2019-10-20.

- ^ van Steenbergen, Jan (2018). "A new era in the history of language invention" (PDF). Linguapax Review.

- ^ "lipu open". Wikipesija. 23 April 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ Knežević, Nenad (2018). "Constructed languages in the whirlwind of the digital revolution". Језик, књижевност и технологија (Jezik, književnost i tehnologija) / Language, Literature and Technology: Proceedings from the Sixth International Conference at the Faculty of Foreign Languages, 19–20 May 2017. Алфа БК универзитет (Alfa BK univerzitet): 16. ISBN 978-86-6461-023-0 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ "toki pona | Facebook". Facebook. Retrieved 2021-09-24.

- ^ "lipu Wesi pi toki pona". Reddit. Retrieved 2021-09-24.

- ^ "Join the ma pona pi toki pona Discord Server!". Discord. Retrieved 2021-09-24.

- ^ "Java Edition 1.18". Minecraft Wiki. Retrieved 2021-11-29.

- ^ meli olin moli. Independently Published. 2020. ISBN 979-8579152343.

|first=missing|last=(help) - ^ "jan pali". lipu tenpo. kulupu pi lipu tenpo. 1 February 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "lipu lawa pi esun kama". jonathangabel.com. Retrieved 2020-08-09.

- ^ "Ave Maria". www.jonathangabel.com. Retrieved 2020-08-10.

- ^ "Toki Pona". Omniglot: the online encyclopedia of writing systems & languages. Retrieved 2019-01-13.

- ^ "ma tomo Pape". suno pona. Retrieved 2019-01-12.

- ^ "Dark Teenage Poetry". tokipona.org. 23 April 2003. Archived from the original on 23 April 2003.

Literature[]

- Lang, Sonja (2014). Toki Pona: The Language of Good. Tawhid. ISBN 978-0978292300. OCLC 921253340.

- This book was translated as: Lang, Sonja (2016). Toki Pona : la langue du bien (in French). Tawhid. ISBN 978-0978292355.

- Lang, Sonja (2021). Toki Pona Dictionary. Illustrated by Vacon Sartirani. Tawhid. ISBN 978-0978292362.

- Cárdenas, Eliazar Parra (2013). Toki pona en 76 ilustritaj lecionoj [Toki Pona in 76 illustrated lessons] (in Esperanto). Translated by Blahuš, Marek. Partizánske, Slovakia: Espero. ISBN 978-80-89366-20-0.

- Toki Pona Stories: akesi seli lili [The Little Dragon]. 2020. ISBN 979-8637271252.

External links[]

- Official website – The creator's website.

- Toki Pona Dictionary

- Bryant Knight (jan Pije)'s lessons at the Wayback Machine (archived March 20, 2020)

- toki pona in 76 Illustrated Lessons

- Toki Pona Wiki

- Where is Toki Pona used? – A page with many links to Toki Pona related websites.

- 2001 introductions

- Constructed languages

- Constructed languages introduced in the 2000s

- Analytic languages

- Engineered languages

- Artistic languages

- Isolating languages

- Taoism in popular culture