Tour Montparnasse

| Tour Maine-Montparnasse | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| General information | |

| Type | Commercial offices |

| Location | 33 Avenue du Maine 15th arrondissement Paris, France |

| Coordinates | 48°50′32″N 2°19′19″E / 48.8421°N 2.3220°ECoordinates: 48°50′32″N 2°19′19″E / 48.8421°N 2.3220°E |

| Construction started | 1969 |

| Completed | 1973 |

| Height | |

| Roof | 210 m (690 ft) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 60 |

| Floor area | 88,400 m2 (952,000 sq ft) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Cabinet Saubot-Jullien Eugène Élie Beaudouin Louis-Gabriel de Hoÿm de Marien Urbain Cassan A. Epstein and Sons International |

| Developer | Wylie Tuttle |

| References | |

| [1][2][3][4] | |

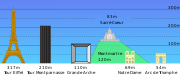

Tour Maine-Montparnasse (Maine-Montparnasse Tower), also commonly named Tour Montparnasse, is a 210-metre (689 ft) office skyscraper located in the Montparnasse area of Paris, France. Constructed from 1969 to 1973, it was the tallest skyscraper in France until 2011, when it was surpassed by the 231-metre (758 ft) Tour First. It remains the tallest building in Paris outside of the La Défense business district. As of February 2020, it is the 14th tallest building in the European Union. The tower was designed by architects Eugène Beaudouin, Urbain Cassan, and Louis Hoym de Marien and built by Campenon Bernard.[5] On September 21, 2017, Nouvelle AOM won a competition to redesign the building's facade.[6]

Description[]

Built on top of the Montparnasse – Bienvenüe Paris Métro station, the building has 59 floors.

The 56th floor, 200 metres from the ground,[7] houses a restaurant called le Ciel de Paris,[8] and the terrace on the top floor, are open to the public for viewing the city.

The view covers a radius of 40 km (25 mi); aircraft can be seen taking off from Orly Airport.

The guard rail, to which various antennae are attached, can be pneumatically lowered.

History[]

The project[]

In 1934, the old Montparnasse station located on the edges of the similarly named boulevard, opposite the Rue de Rennes, appeared ill-suited to traffic. The city of Paris planned to reorganize the district and build a new station. But the project, entrusted to Raoul Dautry (who would give his name to the square of the tower), met strong opposition and was be cancelled.

In 1956, on the occasion of the adoption of the new master plan for the Paris traffic plan, the Société d'économie mixte pour l'Aménagement du secteur Maine Montparnasse (SEMMAM) was created, as well as the l'Agence pour l'Opération Maine Montparnasse (AOM). Their mission was to redevelop the neighbourhood, which requires razing many streets, often dilapidated and unsanitary. The site then occupied up to 8 hectares.

In 1958, the first studies of the tower were well launched, but the project was strongly criticized because of the height of the building. A controversy began, led by the Minister of Public Works Edgard Pisani, who obtained the support of André Malraux, then Minister of Culture under General de Gaulle and led to slowdowns in the project.[9]

However, the reconstruction of the Montparnasse station a few hundred meters south of the old one and the destruction of the Gare du Maine, which was included in the real estate project of the AOM, a joint agency which brought together the four architects: Urbain Cassan, Eugène Beaudouin and Louis de Hoÿm de Marien, was carried out from June 1966 to the spring of 1969 with the assistance of the architect Jean Saubot.

In 1968, André Malraux granted the building permit for the Tower to the AOM and work began that same year.[10] The project was spearheaded by the American real estate developer Wylie Tuttle, who enlisted a consortium of 17 French insurance companies and seven banks in the $140-million multiple-building project, but later distanced himself from the project until his 2002 obituary revealed that the building was his original "brainchild".[11][12][13][14]

It was in 1969 that the decision to build a shopping centre was finally taken. Georges Pompidou, then President of the Republic, wanted to provide the capital with modern infrastructure. And despite a major controversy, the construction of the tower was started.

For geographer Anne Clerval, this construction symbolizes the service economy of Paris in the 1970s resulting from deindustrialization policies which, from the 1960s, favoured "bypassing by space the most working class strongholds at the time".[15]

Construction[]

The Montparnasse tower was built between 1969 and 1973 on the site of the old Montparnasse station. The first stone was laid in 1970 and the inauguration took place in 1973.

The foundations of the tower are made up of 56 reinforced concrete pillars sinking 70 meters underground. For urban planning reasons, the tower had to be built just above a metro line; and to avoid using the same support and weakening it, the metro structures were protected by a reinforced concrete shield. On the other hand, long horizontal beams were installed in order to free up the space needed in the basement to fit out the tracks for trains.[16]

Occupation[]

The tower is mainly occupied by offices. Various companies and organizations have settled in the tower:

- The International Union of Architects, Axa and MMA insurers, the mining and metallurgy company Eramet, Al Jazeera

- Political parties have used campaign offices, such as François Mitterrand in 1974, the RPR in the late 70s, Emmanuel Macron's La République En Marche! in 2016, Benoît Hamon since 2018

- Previously Tour Maine-Montparnasse housed the executive management of Accor.[17]

The 56th floor, with its terrace, bars and restaurant, has been used for private or public events. During the 80s and 90s, the live National Lottery was cast on TF1 from the 56th floor.

Climbing the tower[]

French urban climber Alain "Spiderman" Robert, using only his bare hands and feet and with no safety devices of any kind, scaled the building's exterior glass and steel wall to the top twice, in 1995[18] and in 2015.[19]

His achievement was repeated by Polish climber Marcin Banot in 2020. From the middle of the way he was followed by a lifeguard on a rope but Marcin refused to connect a safety rope and climbed to the top without any help.[20][21]

Criticism[]

The tower's simple architecture, large proportions and monolithic appearance have been often criticized for being out of place in Paris's urban landscape.[22] As a result, two years after its completion the construction of buildings over seven stories high in the city center was banned.[23]

The design of the tower predates architectural trends of more modern skyscrapers today that are often designed to provide a window for every office. Only the offices around the perimeter of each floor of Tour Montparnasse have windows.

It is said that the tower's observation deck enjoys the most beautiful view in all of Paris because it is the only place from which the tower cannot be seen.[24]

A 2008 poll of editors on Virtualtourist voted the building the second-ugliest building in the world, behind Boston City Hall in the United States.[25]

Asbestos contamination[]

In 2005, studies showed that the tower contained asbestos material. When inhaled, for instance during repairs, asbestos is a carcinogen. Monitoring revealed that legal limits of fibers per liter were surpassed and, on at least one occasion, reached 20 times the legal limit. Due to health and legal concerns, some tenants abandoned their offices in the building.[26]

The problem of removing the asbestos material from a large building used by thousands of people is unique. The projected completion time for removal was cited as three years. After a nearly three year delay, removal began in 2009 alongside regular operation of the building. In 2012, it was reported the Maine-Montparnasse Tower was 90% free of asbestos.[27]

Gallery[]

Tour Montparnasse's location in Paris

Office reception hall of Tour Montparnasse

Shopping Arcade of Tour Montparnasse

Tour Montparnasse next to the Eiffel Tower

The Tour Montparnasse seen from the Eiffel Tower

The Tour Montparnasse from the Rue de Rennes

The tower seen from the Jardin du Luxembourg

Night view towards the Eiffel Tower

See also[]

References[]

- ^ "Tour Montparnasse". CTBUH Skyscraper Center.

- ^ Tour Montparnasse at Emporis

- ^ "Tour Montparnasse". SkyscraperPage.

- ^ Tour Montparnasse at Structurae

- ^ "Tour Montparnasse". Vinci. 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ Jessica Mairs (2017). "Tour Montparnasse set to receive "green makeover" by Nouvelle AOM". Dezeen. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ^ "Top Paris restaurants with a view". Paris Digest. 2018. Retrieved 2019-01-03.

- ^ le Ciel de Paris

- ^ "La Tour Montparnasse fête ses quarante ans... de désamour". Le HuffPost (in French). 18 June 2013. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ Batiactu (11 March 2008). "L'histoire de la tour Montparnasse (diaporama)". Batiactu (in French). Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ Pace, Eric (2002-04-06). "Wylie F. L. Tuttle, 79, Force Behind Paris Tower". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-08-31.

- ^ "Bienvenue sur le site de Sefri-Cime". www.sefricime.fr. Retrieved 2021-08-31.

- ^ Marlowe, Lara. "Tour Montparnasse contaminated with asbestos". The Irish Times. Retrieved 2021-08-31.

- ^ Louise

Huxtable, Ada (2002-05-28). "The Myth of the Invulnerable Skyscraper". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2021-08-31. line feed character in

|last=at position 7 (help) - ^ "Anne Clerval: "À Paris, le discours sur la mixité sociale a remplacé la lutte des classes"". L'Humanité (in French). 17 October 2013. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ Batiactu (11 March 2008). "L'histoire de la tour Montparnasse". Batiactu (in French). Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ "Address book." Accor. 17 October 2006. Retrieved on 19 March 2012. "Executive Management Tour Maine-Montparnasse 33, avenue du Maine 75755 Paris Cedex 15 France"

- ^ Ed Douglas, "Vertigo? No problem for Spiderman", Manchester Guardian Weekly, 11 May 1997, p. 30

- ^ "French "spiderman" climbs Paris skyscraper for Nepal". DAWN.COM. 2015-04-29. Retrieved 2020-03-08.

- ^ "Polish tourist climbed Montparnasse". gazeta.pl (in Polish). 2020-09-19. Retrieved 2020-09-27.

- ^ "Climbing Montparnasse". youtube.com (in Polish). 2020-09-18. Retrieved 2020-09-27.

- ^ Montparnasse Tower, a story of passion and hate since 40 years

- ^ Laurenson, John (2013-06-18). "Does Paris need new skyscrapers?". BBC News. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ^ Nicolai Ouroussoff (26 September 2008). "Architecture, Tear Down These Walls". New York Times. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ Belinda Goldsmith (14 November 2008). "Travel Picks: 10 top ugly buildings and monuments". Reuters. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ Marlowe, Lara. "Tour Montparnasse contaminated with asbestos". The Irish Times. Retrieved 2020-03-06.

- ^ "WORKSITE SETUP DURING ASBESTOS REMOVAL WORK ON THE MONTPARNASSE TOWER". EU-OSHA. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tour Montparnasse. |

- Buildings and structures in the 15th arrondissement of Paris

- Buildings and structures in Paris

- Skyscrapers in Paris

- Office buildings completed in 1972

- Skyscraper office buildings in France

- Tourist attractions in Paris