Paris Métro

show This article may be expanded with text translated from the corresponding article in French. (September 2021) Click [show] for important translation instructions. |

| ||

A MF 01 train at Stalingrad | ||

| Overview | ||

|---|---|---|

| Native name | Métropolitain de Paris | |

| Owner | RATP (infrastructure) Île-de-France Mobilités (rolling stock) | |

| Locale | Paris metropolitan area | |

| Transit type | Rapid transit | |

| Number of lines | 16 (numbered 1–14, 3bis and 7bis) | |

| Number of stations | 304[1] | |

| Daily ridership | 4.16 million (2015) | |

| Annual ridership | 1.520 billion (2015)[2] | |

| Operation | ||

| Began operation | 19 July 1900[3] | |

| Operator(s) | RATP | |

| Number of vehicles | 700 trains[citation needed] | |

| Technical | ||

| System length | 225.1 km (139.9 mi)[3] | |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) standard gauge | |

| Electrification | 750 V DC third rail | |

| ||

The Paris Métro (French: Métro de Paris [metʁo də paʁi]; short for Métropolitain [metʁɔpɔlitɛ̃]) is a rapid transit system in the Paris metropolitan area, France. A symbol of the city, it is known for its density within the capital's territorial limits, uniform architecture and unique entrances influenced by Art Nouveau. It is mostly underground and 225.1 kilometres (139.9 mi) long.[3] It has 304 stations, of which 64 have transfers between lines.[1][4] There are 16 lines (with an additional four under construction), numbered 1 to 14, with two lines, 3bis and 7bis, named because they started out as branches of Line 3 and Line 7 respectively. Line 1 and Line 14 are automated, with Line 4 scheduled to be in fall 2022. Lines are identified on maps by number and colour, with the direction of travel indicated by the terminus.

It is the second busiest metro system in Europe, after the Moscow Metro, as well as the tenth busiest in the world.[5] It carried 1.520 billion passengers in 2015, 4.16 million passengers a day, which amounts to 20% of the overall traffic in Paris.[2][6] It is one of the densest metro systems in the world, with 244 stations within the 105.4 km2 (41 sq mi) of the City of Paris. Châtelet–Les Halles, with five Métro and three RER lines, is one of the world's largest metro stations.[7] However, the system has generally poor accessibility, because most stations were built underground well before this became a consideration.

The first line opened without ceremony on 19 July 1900, during the World's Fair (Exposition Universelle).[3] The system expanded quickly until World War I and the core was complete by the 1920s; extensions into suburbs were built in the 1930s. The network reached saturation after World War II with new trains to allow higher traffic, but further improvements have been limited by the design of the network and in particular the short distances between stations. Besides the Métro, central Paris and its urban area are served by five RER lines (developed from the 1960s), ten tramway lines (developed from the 1990s) with an additional four under construction, eight Transilien suburban trains, as well as three VAL lines at Charles de Gaulle Airport and Orly Airport. In the late 1990s, Line 14 was put into service to relieve RER A; it reaching Mairie de Saint-Ouen in 2020 constitutes the network's most recent extension. A large expansion programme is currently under construction with four new orbital Métro lines (15, 16, 17 and 18) around the Île-de-France region, outside Paris city limits. Other extensions are currently under construction on Line 4, Line 11, Line 12 and Line 14. Further plans exist for Line 1 and Line 10, as does a merger of Line 3bis and Line 7bis.

Naming[]

Métro is the abbreviated name of the company that originally operated most of the network: La Compagnie du chemin de fer métropolitain de Paris ("The Paris Metropolitan Railway Company"), shortened to "Le Métropolitain". It was quickly abbreviated to métro, which became a common word to designate all rapid transit systems in France and in many cities elsewhere, an example of a genericized trademark.[8]

The Métro is operated by the Régie autonome des transports parisiens (RATP), a public transport authority that also operates part of the RER network, light rail lines and many bus routes. The name métro was adopted in many languages, making it the most used word for a (generally underground) urban transit system. It is possible that "Compagnie du chemin de fer métropolitain" was copied from the name of London's pioneering underground railway company,[9] the Metropolitan Railway, which had been in business for almost 40 years prior to the inauguration of Paris's first line[citation needed].

History[]

By 1845, Paris and the railway companies were already thinking about an urban railway system to link inner districts of the city. The railway companies and the French government wanted to extend main-line railways into a new underground network, whereas the Parisians favoured a new and independent network and feared national takeover of any system it built.[10] The disagreement lasted from 1856 to 1890. Meanwhile, the population became denser and traffic congestion grew massively. The deadlock put pressure on the authorities and gave the city the chance to enforce its vision.

Prior to 1845, the urban transport network consisted primarily of a large number of omnibus lines, consolidated by the French government into a regulated system with fixed and unconflicting routes and schedules.[11] The first concrete proposal for an urban rail system in Paris was put forward by civil engineer Florence de Kérizouet. This plan called for a surface cable car system.[12] In 1855, civil engineers Edouard Brame and Eugène Flachat proposed an underground freight urban railroad, due to the high rate of accidents on surface rail lines.[12] On 19 November 1871 the General Council of the Seine commissioned a team of 40 engineers to plan an urban rail network.[13] This team proposed a network with a pattern of routes "resembling a cross enclosed in a circle" with axial routes following large boulevards. On 11 May 1872 the Council endorsed the plan, but the French government turned down the plan.[13] After this point, a serious debate occurred over whether the new system should consist of elevated lines or of mostly underground lines; this debate involved numerous parties in France, including Victor Hugo, Guy de Maupassant, and the Eiffel Society of Gustave Eiffel, and continued until 1892.[14] Eventually the underground option emerged as the preferred solution because of the high cost of buying land for rights-of-way in central Paris required for elevated lines, estimated at 70,000 francs per metre of line for a 20 meters (65 ft 7 in)-wide railroad.[15]

The last remaining hurdle was the city's concern about national interference in its urban rail system. The city commissioned renowned engineer Jean-Baptiste Berlier, who designed Paris' postal network of pneumatic tubes, to design and plan its rail system in the early 1890s.[15] Berlier recommended a special track gauge of 1,300 mm (4 ft 3+3⁄16 in) (versus the standard gauge of 1,435 mm or 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) to protect the system from national takeover, which inflamed the issue substantially.[16] The issue was finally settled when the Minister of Public Works begrudgingly recognized the city's right to build a local system on 22 November 1895, and by the city's secret designing of the trains and tunnels to be too narrow for main-line trains, while adopting standard gauge as a compromise with the state.[16]

Fulgence Bienvenüe project[]

On 20 April 1896, Paris adopted the Fulgence Bienvenüe project, which was to serve only the city proper of Paris. Many Parisians worried that extending lines to industrial suburbs would reduce the safety of the city. Paris forbade lines to the inner suburbs and, as a guarantee, Métro trains were to run on the right, as opposed to existing suburban lines, which ran on the left.

Unlike many other subway systems (such as that of London), this system was designed from the outset as a system of (initially) nine lines.[17] Such a large project required a private-public arrangement right from the outset – the city would build most of the permanent way, while a private concessionaire company would supply the trains and power stations, and lease the system (each line separately, for initially 39-year leases).[further explanation needed][17] In July 1897, six bidders competed, and The Compagnie Generale de Traction, owned by the Belgian Baron Édouard Empain, won the contract; this company was then immediately reorganized as the Compagnie du Chemin de Fer Métropolitain.[17]

Construction began in November 1898.[17] The first line, Porte Maillot–Porte de Vincennes, was inaugurated on 19 July 1900 during the Paris World's Fair. Entrances to stations were designed in Art Nouveau style by Hector Guimard. Eighty-six of his entrances are still in existence.

Bienvenüe's project consisted of 10 lines, which correspond to current Line 1 to 9. Construction was so intense that by 1920, despite a few changes from schedule, most lines had been completed. The shield method of construction was rejected in favor of the cut-and-cover method in order to speed up work.[18] Bienvenüe, a highly regarded engineer, designed a special procedure of building the tunnels to allow the swift repaving of roads, and is credited with a largely swift and relatively uneventful construction through the difficult and heterogeneous soils and rocks.[19]

Line 1 and Line 4 were conceived as central east–west and north–south lines. Two lines, ligne 2 Nord (Line 2 North) and ligne 2 Sud (Line 2 South), were also planned but Line 2 South was merged with Line 5 in 1906. Line 3 was an additional east–west line to the north of line 1 and line 5 an additional north to south line to the east of Line 4. Line 6 would run from Nation to Place d'Italie. Lines 7, 8 and 9 would connect commercial and office districts around the Opéra to residential areas in the north-east and the south-west. Bienvenüe also planned a circular line, the ligne circulaire intérieure, to connect the six main-line stations. A section opened in 1923 between Invalides and the Boulevard Saint-Germain before the plan was abandoned.

Nord-Sud competing network[]

On 31 January 1904, a second concession was granted to the Société du chemin de fer électrique souterrain Nord-Sud de Paris (Paris North-South underground electrical railway company), abbreviated to the Nord-Sud (North-South) company. It was responsible for building three proposed lines:

- Line A would join Montmartre to Montparnasse as an additional north–south line to the west of Line 4.

- Line B would serve the north-west of Paris by connecting Saint-Lazare station to Porte de Clichy and Porte de Saint-Ouen.

- Line C would serve the south-west by connecting Montparnasse station to Porte de Vanves. The aim was to connect Line B with Line C, but the CMP renamed Line B as Line 13 and Line C as Line 14. Both were connected by the RATP as the current Line 13.

Line A was inaugurated on 4 November 1910, after being postponed because of floods in January that year. Line B was inaugurated on 26 February 1911. Because of the high construction costs, the construction of line C was postponed. Nord-Sud and CMP used compatible trains that could be used on both networks, but CMP trains used 600 volts third rail, and NS −600 volts overhead wire and +600 volts third rail. This was necessary because of steep gradients on NS lines. NS distinguished itself from its competitor with the high-quality decoration of its stations, the trains' extreme comfort and pretty lighting.

Nord-Sud did not become profitable and bankruptcy became unavoidable. By the end of 1930, the CMP bought Nord-Sud. Line A became Line 12 and Line B Line 13. Line C was built and renamed Line 14; that line was reorganised in 1937 with Lines 8 and 10. This partial line is now the south part of Line 13.

The last Nord-Sud train set was decommissioned on 15 May 1972.[20]

1930–1950: first inner suburbs are reached[]

Bienvenüe's project was nearly completed during the 1920s. Paris planned three new lines and extensions of most lines to the inner suburbs, despite the reluctance of Parisians. Bienvenüe's inner circular line having been abandoned, the already-built portion between Duroc and Odéon for the creation of a new east–west line that became Line 10, extended west to Porte de Saint-Cloud and the inner suburbs of Boulogne.

The line C planned by Nord-Sud between Montparnasse station and Porte de Vanves was built as Line 14 (different from present Line 14). It extended north in encompassing the already-built portion between Invalides and Duroc, initially planned as part of the inner circular. The over-busy Belleville funicular tramway would be replaced by a new line, Line 11, extended to Châtelet. Lines 10, 11 and 14 were thus the three new lines envisaged under this plan.

Most lines would be extended to the inner suburbs. The first to leave the city proper was Line 9, extended in 1934 to Boulogne-Billancourt; more followed in the 1930s. World War II forced authorities to abandon projects such as the extension of Line 4 and Line 12 to the northern suburbs. By 1949, eight lines had been extended: Line 1 to Neuilly-sur-Seine and Vincennes, Line 3 to Levallois-Perret, Line 5 to Pantin, Line 7 to Ivry-sur-Seine, Line 8 to Charenton, Line 9 to Boulogne-Billancourt, Line 11 to Les Lilas and Line 12 to Issy-les-Moulineaux.

World War II had a massive impact on the Métro. Services were limited and many stations closed. The risk of bombing meant the service between Place d'Italie and Étoile was transferred from Line 5 to Line 6, so that most of the elevated portions of the Métro would be on Line 6. As a result, Lines 2 and 6 now form a circle. Most stations were too shallow to be used as bomb shelters. The French Resistance used the tunnels to conduct swift assaults throughout Paris.[21]

It took a long time to recover after liberation in 1944. Many stations had not reopened by the 1960s and some closed for good. On 23 March 1948, the CMP (the underground) and the STCRP (bus and tramways) merged to form the RATP, which still operates the Métro.

1960–1990: development of the RER[]

The network grew saturated during the 1950s. Outdated technology limited the number of trains, which led the RATP to stop extending lines and concentrate on modernisation. The MP 51 prototype was built, testing both rubber-tyred metro and basic automatic driving on the voie navette. The first replacements of the older Sprague trains began with experimental articulated trains and then with mainstream rubber-tyred metro MP 55 and MP 59, some of the latter still in service (Line 11). Thanks to newer trains and better signalling, trains ran more frequently.

The population boomed from 1950 to 1980. Car ownership became more common and suburbs grew further from the centre of Paris. The main railway stations, termini of the suburban rail lines, were overcrowded during rush hour. The short distance between metro stations slowed the network and made it unprofitable to build extensions. The solution in the 1960s was to revive a project abandoned at the end of the 19th century: joining suburban lines to new underground portions in the city centre as the Réseau Express Régional (regional express network; RER).

The RER plan initially included one east–west line and two north–south lines. RATP bought two unprofitable SNCF lines—the Ligne de Saint-Germain (westbound) and the Ligne de Vincennes (eastbound) with the intention of joining them and to serve multiple districts of central Paris with new underground stations. The new line created by this merger became Line A. The Ligne de Sceaux, which served the southern suburbs and was bought by the CMP in the 1930s, would be extended north to merge with a line of the SNCF and reach the new Charles de Gaulle Airport in Roissy. This became Line B. These new lines were inaugurated in 1977 and their wild success outperformed all the most optimistic forecasts to the extent that line A is the most used urban rail line in the world with nearly 300 million journeys a year.

Because of the enormous cost of these two lines, the third planned line was abandoned and the authorities decided that later developments of the RER network would be more cheaply developed by the SNCF, alongside its continued management of other suburban lines. However, the RER developed by the SNCF would never match the success of the RATP's two RER lines. In 1979, the SNCF developed Line C by joining the suburban lines of the Gare d'Austerlitz and Gare d'Orsay, the latter being converted into a museum dedicated to impressionist paintings. During the 1980s, it developed Line D, which was the second line planned by the initial RER schedule, but serving Châtelet instead of République to reduce costs. A huge Métro-RER hub was created at Châtelet–Les Halles, becoming one of the world's largest underground stations.[22]

The same project of the 1960s also decided to merge Line 13 and Line 14 to create a quick connection between Saint-Lazare and Montparnasse as a new north–south line. Distances between stations on the lengthened line 13 differ from that on other lines in order to make it more "express" and hence to extend it farther in the suburbs. The new Line 13 was inaugurated on 9 November 1976.

1990–2010: Eole and Météor[]

In October 1998, Line 14 was inaugurated. It was the first fully new Métro line in 63 years. Known during its conception as Météor (Métro Est-Ouest Rapide), it is one of the two fully automatic lines within the network along with Line 1. It was the first with platform screen doors to prevent suicides and accidents. It was conceived with extensions to the suburbs in mind, similar to the extensions of the line 13 built during the 1970s. As a result, most of the stations are at least a kilometre apart. Like the RER lines designed by the RATP, nearly all stations offer connections with multiple Métro lines. The line runs between Saint-Lazare and Olympiades.

Lines 13 and 7 are the only two on the network to be split in branches. The RATP would like to get rid of those saturated branches in order to improve the network's efficiency. A project existed to attribute to line 14 one branch of each line, and to extend them further into the suburbs. This project was abandoned. In 1999, the RER Line E was inaugurated. Known during its conception as Eole (Est-Ouest Liaison Express), it is the fifth RER line. It terminates at Haussmann–Saint-Lazare, but a new project, financed by EPAD, the public authority managing the La Défense business district, should extend it west to La Défense–Grande Arche and the suburbs beyond.

2010 and beyond: automation[]

In work started in 2007 and completed in November 2011, Line 1 was converted to driverless operation. The line was operated with a combination of driver-operated trains and driver-less trains until the delivery of the last of its driver-less MP 05 trains in February 2013. The same conversion is on-going for Line 4, with an expected completion date in 2022.

Several extensions to the suburbs opened in the last years. Line 8 was extended to Pointe du Lac in 2011, line 12 was extended to Aubervilliers in 2012, line 4 was extended to Mairie de Montrouge in 2013 and Line 14 was extended by 5.8 km (3.6 mi) to Mairie de Saint-Ouen in December 2020.

Accidents and incidents[]

- 10 August 1903: Couronnes Disaster (fire), 84 killed.

- July – October 1995: Paris Métro bombings (terror attack), committed by Algerian extremists – 8 killed and more than 100 injured.

- 30 August 2000: an MF 67 train derailed due to excessive speed and unavailable automatic cruising at Notre-Dame-de-Lorette, 24 slightly injured.

- 6 August 2005: fire broke out on a train at Simplon, injuring at least 19 people. Early reports blamed an electrical short circuit as the cause.

- 29 July 2007: a fire started on a train between Varenne and Invalides. Fifteen people were injured.

Network[]

Since the Métro was built to comprehensively serve the city inside its walls, the stations are very close: 548 metres apart on average, from 424 m on Line 4[23] to one kilometre on the newer line 14, meaning Paris is densely networked with stations.[24] The surrounding suburbs are served by later line extensions, thus traffic from one suburb to another must pass through the city. The slow average speed effectively prohibits service to the greater Paris area.

The Métro is mostly underground (197 km or 122 mi of 214 km or 133 mi). Above-ground sections consist of elevated railway viaducts within Paris (on Lines 1, 2, 5 and 6) and the suburban ends of Lines 1, 5, 8, and 13. The tunnels are relatively close to the surface due to the variable nature of the terrain, which complicates deep digging; exceptions include parts of Line 12 under the hill of Montmartre and line 2 under Ménilmontant. The tunnels follow the twists and turns of the streets above. During construction in 1900, a minimum radius of curvature of just 75 metres was imposed, but even this low standard was not adhered to at Bastille and Notre-Dame-de-Lorette.

Like the New York City Subway and in contrast with the London Underground the Paris Métro mostly uses two-way tunnels. As in most French métro and tramway systems, trains drive on the right (SNCF trains run on the left track). The tracks are standard gauge (1435 cm). Electric power is supplied by a third rail which carries 750 volts DC.

The width of the carriages, 2.4 metres (7 ft 10 in), is narrower than that of newer French systems (such as the 2.9 metres (9 ft 6 in) carriages in Lyon, one of the widest in Europe)[25][26] and trains on Lines 1, 4 and 14 have capacities of 600-700 passengers; this is as compared with 2,600 on the Altéo MI 2N trains of RER A. The City of Paris deliberately chose the narrow size of the Metro tunnels to prevent the running of main-line trains; the city of Paris and the French state had historically poor relations.[17] In contrast to many other historical metro systems (such as New York, Madrid, London, and Boston), all lines have tunnels and operate trains with the same dimensions. Five Paris Métro Lines (1, 4, 6, 11 and 14) run on a rubber tire system developed by the RATP in the 1950s, exported to the Montreal, Santiago, Mexico City and Lausanne metros.

The number of cars in each train varies line by line. The shortest are lines 3bis and 7bis with three-car trains. Line 11 currently runs with four but will be expanded to five in the future. Lines 1 and 4 run six-car trains. Line 14 currently runs a mix of six and 8-car trains; in the future it will only run 8 cars. All other lines run with five. Two lines, 7 and 13, have branches at the end, and trains serve every station on each line except when they are closed for renovations.

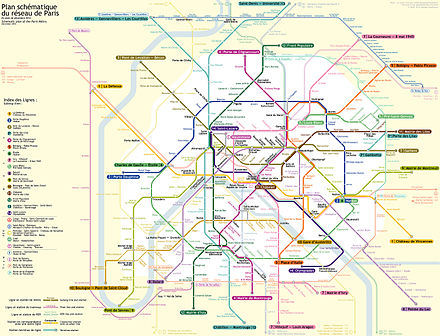

Map[]

Opening hours[]

The first train leaves each terminus at 5:30 a.m. On some lines additional trains start from an intermediate station. The last train, often called the "balai" (broom) because it sweeps up remaining passengers, arrives at the terminus at 1:15 a.m., except on Fridays (since 7 December 2007),[27] Saturdays and on nights before a holiday, when the service ends at 2:15 a.m.

On New Year's Eve, Fête de la Musique, Nuit Blanche and other events, some stations on Lines 1, 4, 6, 9 and 14 remain open all night.

Tickets[]

Fares are sold at kiosks and at automated machines in the station foyer. Entrance to platforms is by automated gate, opened by smart cards and simple tickets. Gates return tickets for passengers to retain for the duration of the journey. There is normally no system to collect or check tickets at the end of the journey, and tickets can be inspected at any point. The exit from all stations is clearly marked as to the point beyond which possession of a ticket is no longer required.

The standard ticket is ticket "t+". It is valid for a multi-transfer journey within one and a half hours from the first validation. It can be used on the Métro, buses and trams, and in zone 1 of the RER. It allows unlimited transfers between the same mode of transport (i.e. Métro to Métro, bus to bus and tram to tram), between bus and tram, and between metro and RER zone 1. When transferring between the Metro and the RER, it is necessary to retain the ticket. The RER requires a valid ticket for entry and exit, even for a transfer. It costs €1.90 or ten (a carnet) for €16.90 as of March 2020.[28] The carnet option will be phased out for paper tickets by March 2022. [29]

Other fares use the Navigo card (the name being a portmanteau from the French terms navigation and Parigot, a nickname for Parisians), an RFID-based contactless smart card. Fares include:

- daily (Mobilis; the Ticket Jeunes, for youth under 26 years on weekends and national holidays, is half the cost of a Mobilis pass);[30]

- weekly or monthly (the former Carte orange, sold as the weekly Navigo ("hebdo") and the monthly Navigo);

- yearly (Navigo intégrale, or Imagine R for students);

- The (Paris Visite) travel card is available for one, two, three or five days, for zones 1–3 covering the centre of Paris, or zones 1–5 covering the whole of the network including the RER to the airports, Versailles and Disneyland Paris. It was conceived mainly for visitors and is available through RATP's distributors in the UK, Switzerland and Belgium. It may be a better deal to buy a weekly card (up to €10 saving) but a weekly card runs from Monday to Monday (and is reset every Monday), whereas the Paris Visite card is valid for the number of days purchased.

Facilities[]

On 26 June 2012 it was announced that the Métro would get Wi-Fi in most stations. Access provided would be free, with a premium paid alternative offer proposed for a faster internet connection.[31]

Technical specifications[]

The Métro has 214 kilometres (133 mi) of track[3] and 302 stations,[1] 62 connecting between lines.[4] These figures do not include the RER network. The average distance between stations is 562 m (1,844 ft). Trains stop at all stations.[32] Lines do not share tracks, even at interchange (transfer) stations.[26]

Trains average 20 km/h (12.4 mph) with a maximum of 70 km/h (43 mph) on all but the automated driverless trains of Line 14, which average 40 km/h (25 mph) and reach 80 km/h (50 mph). An average interstation trip takes 58 seconds.[33] Trains travel on the right. The track is standard gauge but the loading gauge is smaller than the mainline SNCF network. Power is from a lateral third rail, 750 V DC, except on the rubber-tyred lines where the current is from guide bars.[26]

The loading gauge is small compared to those of newer metro systems (but comparable to that of early European metros), with capacities of between about 560 and 720 passengers per train on Lines 1–14. Many other metro systems (such as those of New York and London) adopted expanded tunnel dimensions for their newer lines (or used tunnels of multiple sizes almost from the outset, in the case of Boston), at the cost of operating incompatible fleets of rolling stock. Paris built all lines to the same dimensions as its original lines. Before the introduction of rubber-tire lines in the 1950s, this common shared size theoretically allowed any Métro rolling stock to operate on any line, but in practice each line was assigned a regular roster of trains.[citation needed]

A feature is the use of rubber-tired trains on five lines: this technique was developed by RATP and entered service in 1951.[34] The technology was exported to many networks around the world (including Montreal, Mexico City and Santiago). Lines 1, 4, 6, 11 and 14 have special adaptations to accommodate rubber-tyred trains. Trains are composed of 3 to 6 cars depending on the line, the most common being 5 cars (Line 14 may have 8 cars in the future), but all trains on the same line have the same number of cars.

The Metro is designed to provide local, point-to-point service in Paris proper and service into the city from some close suburbs. Stations within Paris are very close together to form a grid structure, ensuring that every point in the city is close to a metro station (less than 500 metres or 1,640 feet), but this makes the service slow 20 km/h (12 mph), except on Line 14 where the stations are farther apart and the trains travel faster. The low speed virtually precludes feasible service to farther suburbs, which are serviced by the RER.

The Paris Métro runs mostly underground; surface sections include sections on viaduct in Paris (Lines 1, 2, 5, and 6) and at the surface in the suburbs (Lines 1, 5, 8, and 13). In most cases, both tracks are laid in a single tunnel. Almost all lines follow roads, having been built by the cut-and-cover method near the surface (the earliest by hand). Line 1 follows the straight course of the Champs-Elysées and on other lines, some stations (Liège, Commerce) have platforms that do not align: the street above is too narrow to fit both platforms opposite each other. Many lines have very sharp curves. The specifications established in 1900 required a very low minimum curve radius by railway standards, but even this was often not fully respected, for example near Bastille and Notre Dame de Lorette. Parts of the network are built at depth, in particular a section of Line 12 under Montmartre, the sections under the Seine, and all of Line 14.

Lines 7 and 13 have two terminal branches, while line 7bis runs in a unidirectional loop at one end. One end of lines 2 and 5 each and both ends of line 6 have their terminus station on a balloon loop. One end of lines 3bis and 7bis each have their trains essentially operate this way, but instead reverse. One end of lines 2, 3bis, and 4 have trains run out of service on a balloon loop before reentering service. All other termini have trains continue a certain distance beyond the terminal, before proceeding back to the station on a different platform headed the other way.

Rolling stock[]

The rolling stock has steel-wheel (MF for matériel fer) and rubber-tyred trains (MP for matériel pneu). The different versions of each kind are specified by year of design. (C for Conduite Conducteur) and (CA for Conduite Automatique)

- Steel-wheeled rolling stock

- Rubber-tyred rolling stock

- No longer in service

- M1: in service from 1900 until 1931.

- Sprague-Thomson: in service from 1908 until 1983.

- MA 51: in service on lines 10 and 13 until 1994.

- MP 55: in service on Line 11 from 1956 until 1999, replaced by the MP 59.

- Zébulon a prototype MF 67, used for training operators between 1968 and 2010. It never saw passenger service.

- Not yet in service

- : intended to replace the MF 67, MF 77 and MF 88 stocks on Lines 3, 3 bis, 7, 7 bis, 8, 10, 12 and 13.

Lines[]

| Line | Opened | Last extension |

Stations served |

Length | Average interstation |

Journeys made (2017) |

Termini | Rolling stock |

Conduction system | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Line 1 | 1900 | 1992 | 25 | 16.6 km / 10.3 miles | 692 m | 181.2 million | La Défense Château de Vincennes |

MP 05 | Automatic (SAET) | |

| Line 2 | 1900 | 1903 | 25 | 12.3 km / 7.7 miles | 513 m | 105.2 million | Porte Dauphine Nation |

MF 01 | Conductor (PA) | |

| Line 3 | 1904 | 1971 | 25 | 11.7 km / 7.3 miles | 488 m | 101.4 million | Pont de Levallois–Bécon Gallieni |

MF 67 | Conductor (OCTYS) | |

| Line 3bis | 1971 | N/A | 4 | 1.3 km / 0.8 miles | 433 m | Porte des Lilas Gambetta |

MF 67 | Conductor | ||

| Line 4 | 1908 | 2013 | 27 | 12.1 km / 6.6 miles | 438 m | 155.9 million | Porte de Clignancourt Mairie de Montrouge |

MP 89CC | Conductor (PA) | |

| Line 5 | 1906 | 1985 | 22 | 14.6 km / 9.1 miles | 697 m | 110.9 million | Bobigny–Pablo Picasso Place d'Italie |

MF 01 | Conductor | |

| Line 6 | 1909 | 1942 | 28 | 13.7 km / 8.5 miles | 507 m | 114.3 million | Charles de Gaulle–Étoile Nation |

MP 73 | Conductor | |

| Line 7 | 1910 | 1987 | 38 | 22.5 km / 14.0 miles | 608 m | 135.1 million | La Courneuve–8 mai 1945 Villejuif–Louis Aragon Mairie d'Ivry |

MF 77 | Conductor | |

| Line 7bis | 1967 | N/A | 8 | 3.1 km / 1.9 miles | 443 m | Louis Blanc Pré-Saint-Gervais |

MF 88 | Conductor | ||

| Line 8 | 1913 | 2011 | 38 | 23.4 km / 13.8 miles | 614 m | 105.5 million | Balard Pointe du Lac |

MF 77 | Conductor | |

| Line 9 | 1922 | 1937 | 37 | 19.6 km / 12.2 miles | 544 m | 137.9 million | Pont de Sèvres Mairie de Montreuil |

MF 01 | Conductor | |

| Line 10 | 1923 | 1981 | 23 | 11.7 km / 7.3 miles | 532 m | 45.3 million | Boulogne–Pont de Saint-Cloud Gare d'Austerlitz |

MF 67 | Conductor | |

| Line 11 | 1935 | 1937 | 13 | 6.3 km / 3.9 miles | 525 m | 47.1 million | Châtelet Mairie des Lilas |

MP 59 MP 73 |

Conductor | |

| Line 12 | 1910[35] | 2012 | 29 | 15.3 km / 9.5 miles | 545 m | 84.3 million | Front Populaire Mairie d'Issy |

MF 67 | Conductor (PA) | |

| Line 13 | 1911[35] | 2008 | 32 | 24.3 km / 15.0 miles | 776 m | 131.4 million | Châtillon–Montrouge Saint-Denis–Université Les Courtilles |

MF 77 | Conductor (OURAGAN) | |

| Line 14 | 1998 | 2020 | 13 | 13.9 km / 8.6 miles | 1,158 m | 83.3 million | Mairie de Saint-Ouen Olympiades |

MP 89CA MP 05 MP 14 |

Automatic (SAET) | |

Planned lines[]

This template lists the lines of the Paris Métro currently planned to open as part of the Grand Paris Express project.

| Line | Planned opening |

Planned completion[36] |

Stations served |

Length | Average interstation |

Termini | Rolling stock |

Conduction system | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Line 15 | 2025 | 2030 | 36 | 75 km / 47 miles | 2,083 m | Noisy–Champs Champigny Centre |

Future steel-wheeled trains | Automatic | |

| Line 16 | 2024 | 2024 | 10 | 25 km / 16 miles[37] | 2,778 m | Noisy–Champs Saint-Denis Pleyel |

Future steel-wheeled trains | Automatic | |

| Line 17 | 2025 | 2030 | 9 | 25 km / 16 miles[37] | 3,125 m | Le Mesnil-Amelot Saint-Denis Pleyel |

Future steel-wheeled trains | Automatic | |

| Line 18 | 2023 | 2030 | 13 | 50 km / 31 miles | 4,167 m | Orly Airport Versailles-Chantiers |

Future steel-wheeled trains | Automatic | |

Stations[]

The typical station comprises two central tracks flanked by two four-metre wide platforms. About 50 stations, generally current or former termini, are exceptions; most have three tracks and two platforms (Porte d'Orléans), or two tracks and a central platform (Porte Dauphine). Some stations are single-track, either due to difficult terrain (Saint-Georges), a narrow street above (Liège) or track loops (Église d'Auteuil).

Station length was originally 75 m. This was extended to 90 m on high-traffic lines (Line 1 and Line 4), with some stations at 105 m (the difference as yet unused).

In general, stations were built near the surface by the cut-and-cover method, and are vaulted. Stations of the former Nord-Sud network (Line 12 and Line 13) have higher ceilings, due to the former presence of a ceiling catenary. There are exceptions to the rule of near-surface vaulting:

- Stations particularly close to the surface, generally on Line 1 (Champs-Elysées–Clémenceau), have flat metal ceilings.

- Elevated (above-street) stations, in particular on Line 2 and Line 6, are built in brick and covered by platform awnings (Line 2) or glass canopies (Line 6).

- Stations on the newest sections (Line 14), built at depth, comprise 120 m platforms, high ceilings and double-width platforms. Since the trains on this line are driverless, the stations have platform screen doors. Platform screen doors have been introduced on Line 1 as well since the MP 05 trains have been functioning.

Several ghost stations are no longer served by trains. One of the three platforms at Porte des Lilas station is on a currently unused section of track, often used as a backdrop in films.

In 2018, the busiest stations were Saint-Lazare (46.7 millions of passengers), Gare du Nord (45.8), Gare de Lyon (36.9), Montparnasse – Bienvenüe (30.6), Gare de l'Est (21.4), Bibliothèque François Mitterrand (18.8), République (18.3), Les Halles (17.5), La Défense (16.0) and Bastille (13.2).[38]

Interior decoration[]

Concourses are decorated in Art Nouveau style defined at the Métro's opening in 1900. The spirit of this aesthetic has generally been respected in renovations.

Standard vaulted stations are lined by small white earthenware tiles, chosen because of the poor efficiency of early twentieth century electric lighting. From the outset walls have been used for advertising; posters in early stations are framed by coloured tiles with the name of the original operator (CMP or Nord Sud). Stations of the former Nord Sud (most of line 12 and parts of line 13) generally have more meticulous decoration. Station names are usually inscribed on metallic plaques in white letters on a blue background or in white tiles on a background of blue tiles.

The first renovations took place after the Second World War, when the installation of fluorescent lighting revealed the poor state of the original tiling. Three main styles of redecoration followed in succession.

- Between 1948 and 1967 the RATP installed standardised coloured metallic wall casings in 73 stations.

- From the end of the 1960s a new style was rolled out in around 20 stations, known as Mouton-Duvernet after the first station concerned. The white tiles were replaced to a height of 2 m with non-bevelled tiles in various shades of orange. Intended to be warm and dynamic, the renovations proved unpopular. The decoration has been removed as part of the "Renouveau du métro" programme.

- From 1975 some stations were redecorated in the Motte style, which emphasised the original white tiling but brought touches of colour to light fixtures, seating and the walls of connecting tunnels. The subsequent Ouï Dire style features audaciously shaped seats and light housings with complementary multi-coloured uplighting.

A number of stations have original decorations to reflect the cultural significance of their locations. The first to receive this treatment was Louvre – Rivoli on line 1, which contains copies of the masterpieces on display at the museum. Other notable examples include Bastille (line 1), Saint-Germain-des-Prés (line 4), Cluny – La Sorbonne (line 10) and Arts et Métiers (line 11).

Exterior decoration[]

The original Art Nouveau entrances are iconic symbols of Paris. There are currently 83 of them. Designed by Hector Guimard in a style that caused some surprise and controversy in 1900, there are two main variants:

- The most elaborate feature glass canopies. Two original canopies still exist, at Porte Dauphine and Abbesses (originally located at Hôtel de Ville until moved in the 1970s). A replica of the canopy at Abbesses was installed at Châtelet station at the intersection of Rue des Halles and Rue Sainte-Opportune.

- A cast-iron balustrade decorated in plant-like motifs, accompanied by a "Métropolitain" sign supported by two orange globes atop ornate cast-iron supports in the form of plant stems.

- Several of the iconic Guimard entrances have been given to other cities. The only original one on a metro station outside Paris is at Square-Victoria-OACI station in Montreal, as a monument to the collaboration of RATP engineers. Replicas cast from the original moulds have been given to the Lisbon Metro (Picoas station); the Mexico City Metro (Metro Bellas Artes, with a "Metro" sign), offered as a gift in return for a Huichol mural displayed at Palais Royal – Musée du Louvre; and Chicago Metra (Van Buren Street, at South Michigan Avenue and East Van Buren Street, with a "Metra" sign), given in 2001. The Moscow Metro has a Guimard entrance at Kievskaya station, donated by the RATP in 2006. There is an entrance on display at the Sculpture Garden in Downtown Washington, D.C. This does not lead to a metro station, it is just for pleasure. Similarly, The Museum of Modern Art has an original, restored Guimard entrance outdoors in the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden.[39]

Later stations and redecorations have brought increasingly simple styles to entrances.

- Classical stone balustrades were chosen for some early stations in prestigious locations (Franklin D. Roosevelt, République).

- Simpler metal balustrades accompany a "Métro" sign crowned by a spherical lamp in other early stations (Saint-Placide).

- Minimalist stainless-steel balustrades (Havre-Caumartin) appeared from the 1970s and signposts with just an "M" have been the norm since the war (Olympiades, opened 2007).

A handful of entrances have original architecture (Saint-Lazare); a number are integrated into residential or standalone buildings (Pelleport).

Future[]

Under construction[]

- A 1.9 km (1.2 mi) extension of Line 4 to the south from Mairie de Montrouge to Bagneux with two new stations.[40] Opening of this section is currently scheduled for the end of 2021.[40][41]

- A 6 km (3.7 mi) extension of Line 11 to the east from Mairie des Lilas to Rosny-Bois-Perrier RER with six new stations.[42] Opening of this section is currently scheduled for 2023.[42]

- A 3.2 km (2.0 mi) extension of Line 12 to the north from Front Populaire to Mairie d'Aubervilliers with two new stations.[43] Opening of this section is currently scheduled for Spring 2022.[43][44]

- As part of the Grand Paris Express project:[45]

- A 14 km (8.7 mi) extension of Line 14 to the south from Olympiades to Orly Airport with seven new stations.[46] Opening of this section is currently scheduled for 2024.[47]

- An extension of Line 14 to the north from Mairie de Saint-Ouen to Saint-Denis Pleyel with one new station. Opening of this section is currently scheduled for 2024.[45]

- The first (southern) section of future Line 15 between Pont de Sèvres and Noisy–Champs RER. This section is 33 km (21 mi) long and will have sixteen stations.[48][45] Opening is currently planned for 2025.[49][50]

- The first (northern) section of future Line 16 between Saint-Denis Pleyel and Clichy–Montfermeil with seven new stations.[45] Opening is currently planned for 2026.[51][50]

- The first (southern) section of future Line 17 between Le Bourget RER and Le Bourget–Aéroport with one new station.[45] Opening is currently planned for 2026.[52][50]

Planned[]

- Grand Paris Express, a project that includes a 75 kilometres (47 mi) circular line around Paris with 4 new lines of Paris Métro : Lines 15, 16, 17 and 18. Line 15, the longest of the new lines, will be a circular line around Paris. Line 17 will run to Charles de Gaulle Airport. The two others lines will serve the suburban area of Paris. Grand Paris Express will have a total span of 200 kilometres (120 mi) and count 68 stations. Grand Paris Express will dramatically improve transportation in the Paris metropolitan area for one million passengers daily starting in 2024 with the inauguration of the southern section of circular line 15.[53][50]

- An extension of Line 1 from Château de Vincennes to Val de Fontenay station (no official timeline).[54]

- An extension of Line 10 from Gare d'Austerlitz to Ivry–Place Gambetta or even Les Ardoines station (not before 2030).[55]

Proposed[]

In addition to the projects already under construction or currently being actively studied, there have also been proposals for:

- An extension of Line 5 to Place de Rungis (south) and Drancy (north), as well as a new infill station (Bobigny – La Folie).

- An extension of Line 7 to Le Bourget RER.

- An extension of Line 9 to Montreuil–Hôpital.

- An extension of Line 11 from its future terminus station at Rosny-Bois-Perrier RER to Noisy–Champs RER.

- An extension of Line 12 to Issy-les-Moulineaux RER.

- A merger of Line 3bis and Line 7bis to form a new line.

Cultural significance[]

The Métro has a cultural significance that goes well beyond the City of Paris. The name Métropolitan (or Métro) has become a generic name for subways and urban underground railroads.

The station entrance kiosks, designed by Hector Guimard, fostered Art Nouveau building style (once widely known as "le style Métro"),[56] though, some French commentators criticized the Guimard station kiosks, including their green colour and sign lettering, as difficult to read.[57]

The success of rubber-tired lines led to their export to metro systems around the world, starting with the Montreal Metro.[58] The success of Montreal "did much to accelerate the international subway boom" of the 1960s/1970s and "assure the preeminence of the French in the process.[59] Rubber-tired systems were adopted in Mexico City, Santiago, Lausanne, Turin, Singapore and other cities. The Japanese adopted rubber-tired metros (with their own technology and manufacturing firms) to systems in Kobe, Sapporo, and parts of Tokyo.

The "Rabbit of Paris Métro" is an anthropomorphic rabbit visible on stickers on the doors of the trains since 1977 to advise passengers (especially children) of the risk of getting one's hands trapped when the doors are opening, as well as the risk of injury on escalators or becoming trapped in the closing doors. This rabbit is now a cultural icon in Paris similar to the "mind the gap" phrase in London.

See also[]

- Architecture of the Paris Métro

- List of stations of the Paris Métro

- Transport in Paris

- Paris in the Belle Époque

- Transportation in France

- Rubber-tyred metro

- List of metro systems

- Rail transport in France

References[]

Notes

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "The Metro: a Parisian institution". RATP. Archived from the original on 18 February 2017. Retrieved 29 January 2014. The Montmartre funicular is considered to be part of the metro system, within which is represented by a 303rd fictive station "Funiculaire".

- ^ Jump up to: a b "RAPPORT D'ACTIVITÉ 2015" (PDF). STIF. p. 18. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Brief history of the Paris metro". france.fr – The official website of France. Archived from the original on 26 September 2013. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Statistiques Syndicat des transports d'Île-de-France rapport 2005 (in French) states 297 stations + Olympiades + Les Agnettes + Les Courtilles Archived 17 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 17 September 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Demade 2015, p. 13.

- ^ [1] Archived 15 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Has metro become a generic trademark?". genericides.org. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ Connor, Liz (1 July 2016). "10 incredible facts you may not know about the Metropolitan line". www.standard.co.uk.

- ^ Bobrick, Benson. Labyrinths of Iron: A History of the World's Subways. New York: Newsweek Books, 1981. p135

- ^ Bobrick, Benson. Labyrinths of Iron: A History of the World's Subways. New York: Newsweek Books, 1981. p138-140

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bobrick, Benson. Labyrinths of Iron: A History of the World's Subways. New York: Newsweek Books, 1981. p141

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bobrick, Benson. Labyrinths of Iron: A History of the World's Subways. New York: Newsweek Books, 1981. p142

- ^ Bobrick, Benson. Labyrinths of Iron: A History of the World's Subways. New York: Newsweek Books, 1981. p142-148

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bobrick, Benson. Labyrinths of Iron: A History of the World's Subways. New York: Newsweek Books, 1981. p148

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bobrick, Benson. Labyrinths of Iron: A History of the World's Subways. New York: Newsweek Books, 1981. p148-9

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Bobrick, Benson. Labyrinths of Iron: A History of the World's Subways. New York: Newsweek Books, 1981. p. 149.

- ^ Bobrick, Benson. Labyrinths of Iron: A History of the World's Subways. New York: Newsweek Books, 1981. p. 151.

- ^ Bobrick, Benson. Labyrinths of Iron: A History of the World's Subways. New York: Newsweek Books, 1981. p. 150-1,162

- ^ "1968–1983 : le RER et la modernisation du réseau parisien" [1968–1983: The RER and the modernisation of the parisian network]. Musée des Transports – Histoire du Métropolitain de Paris (in French). Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- ^ Bobrick, Benson. Labyrinths of Iron: A History of the World's Subways. New York: Newsweek Books, 1981. p. 286.

- ^ Aplin, Richard; Montchamp, Joseph (2014). Dictionary of Contemporary France. Routledge. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-135-93646-4.

- ^ Jean Tricoire, Un siècle de métro en 14 lignes, p. 188

- ^ Jean Tricoire, op. cit., p. 330

- ^ Jean Tricoire. Un siècle de métro en 14 lignes. De Bienvenüe à Météor.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Clive Lamming, Métro insolite

- ^ "Press statement from RATP 2 October 2007" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009.

- ^ "Accueil – Ticket "t"". Ratp.info. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ "Dans moins d'un an, vous ne pourrez plus acheter de carnets de tickets de métro en papier". leparisien.fr. 25 May 2021.

- ^ "Accueil –Ticket jeune". RATP. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ "Le Wi-Fi gratuit arrive dans le métro parisien". Archived from the original on 30 October 2012.

- ^ On 1 January 2006, a test was done with few lines opening at night on main stops only.

- ^ "30 things about the Paris Metro that even Parisians don't know". The Earful Tower. 10 August 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ Bobrick, Benson. Labyrinths of Iron: A History of the World's Subways. New York: Newsweek Books, 1981. p312

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lines 12 and 13 were originally built as part of the Nord-Sud network (as Line A and Line B respectively).

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20141119113117/http://www.stif.org/developpements-avenir/nouveau-grand-paris/metro/projets/lignes-16-17-18-du-nouveau-grand-paris-4899.html

- ^ "Trafic annuel entrant par station du réseau ferré 2018". data.ratp.fr (in French). Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ [2].

- ^ Jump up to: a b Île-de-France Mobilités. "Métro 4, prolongement et automatisation Montrouge > Bagneux" (PDF) (in French). Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- ^ dubois. "Métro prolongement de la ligne 4". Ville de Bagneux (92) (in French). Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Île-de-France Mobilités. "Métro 11, prolongement Mairie des Lilas > Rosny-Bois-Perrier" (PDF) (in French). Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Île-de-France Mobilités. "Métro 12, prolongement Front Populaire > Mairie d'Aubervilliers" (PDF) (in French). Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- ^ Haus, Hélène (15 October 2020). "Nouveau retard de la ligne 12 : les habitants d'Aubervilliers dépités". leparisien.fr (in French). Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Grand Paris Express, the largest transport project in Europe". Société du Grand Paris (in French). 16 June 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ "Prolongement de la ligne 14 à Mairie de Saint-Ouen" (in French). Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- ^ "Ligne 14 Sud". Société du Grand Paris (in French). 30 March 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ "Grand Paris Express Ligne 15 Sud" (in French). 12 April 2018. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- ^ "Ligne 15 Sud". Société du Grand Paris (in French). 2 May 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "La Société du Grand Paris réactualise le calendrier du Grand Paris Express". Société du Grand Paris (in French). 15 July 2021. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- ^ "Ligne 16". Société du Grand Paris (in French). 2 May 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ "Ligne 17". Société du Grand Paris (in French). 2 May 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ "Grand Paris facts. Grand Paris Express". Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- ^ "Prolongement du Métro ligne 1 à Val de Fontenay, le projet en bref" (in French). Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- ^ "Prolongement de la ligne 10 à Ivry Gambetta" (in French). Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- ^ Bobrick, Benson. Labyrinths of Iron: A History of the World's Subways. New York: Newsweek Books, 1981. p155, 165

- ^ Bobrick, Benson. Labyrinths of Iron: A History of the World's Subways. New York: Newsweek Books, 1981. p155-6, 165

- ^ Bobrick, Benson. Labyrinths of Iron: A History of the World's Subways. New York: Newsweek Books, 1981. p318-9

- ^ Bobrick, Benson. Labyrinths of Iron: A History of the World's Subways. New York: Newsweek Books, 1981. p319

Bibliography

- Bindi, A., & Lefeuvre, D. (1990). Le Métro de Paris : Histoire d'hier à demain, Rennes : Ouest-France. ISBN 2-7373-0204-8. (French)

- Demade, Julien (2015). Les embarras de Paris, ou l'illusion techniciste de la politique parisienne des déplacements. L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-343-06517-5.

- Descouturelle, Frédéric, et al. (2003). Le métropolitain d'Hector Guimard. Somogy. ISBN 2-85056-815-5. (French)

- Gaillard, M. (1991). Du Madeleine-Bastille à Météor : Histoire des transports Parisiens, Amiens : Martelle. ISBN 2-87890-013-8. (French)

- Hovey, Tamara. Paris Underground, New York: Orchard Books, 1991. ISBN 0-531-05931-6.

- Lamming, C.(2001) Métro insolite, Paris : Parigramme, ISBN 2-84096-190-3.

- Ovenden, Mark. Paris Metro Style in map and station design, London: Capital Transport, 2008. ISBN 978-1-85414-322-8.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paris Metro. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Paris. |

- RATP English version. Contains routes, schedules, journey times, etc.

- Comprehensive map of the Paris Metro network

- Real-distance network map at CityRailTransit website

- UrbanRail.Net – descriptions of all metro systems in the world, each with a schematic map showing all stations.

- Métro Paris – descriptions of all metro stations in Paris : maps, lines and schedules

- Paris Métro templates

- Paris Métro

- Underground rapid transit in France

- Rail transport in Paris

- RATP Group

- Electric railways in France

- Railway lines opened in 1900

- 1900 establishments in France