Vaps Movement

Vaps Movement Eesti Vabadussõjalaste Liit | |

|---|---|

| |

| Leader | Andres Larka and Artur Sirk |

| Founded | 1929 |

| Banned | December 1935 |

| Ideology | Estonian nationalism[1] Anti-communism Populism |

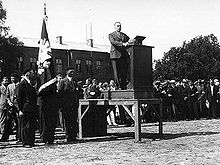

Vaps Movement,[2] (Estonian: Eesti Vabadussõjalaste Keskliit, later Eesti Vabadussõjalaste Liit, vabadussõjalased, or colloquially vapsid, a single member of this movement was called vaps) the Union of Participants in the Estonian War of Independence[3] was founded as an Estonian association of veterans of the Estonian War of Independence (1918–1920). Later non-veterans were accepted as its supporter-members. The organisation was founded in 1929, and emerged as a mass anti-communist and anti-parliamentary movement.[2] The leaders of this association were Andres Larka (formal figurehead and presidential candidate) and Artur Sirk.

The Vaps Movement was a paramilitary anti-socialist organisation led by former officers of the Russian Tsar's Army,[4] with most of its base being veterans of the Estonian War of Independence.[5] Early support for the movement came from campaigns to financially uplift Estonian veterans, and redistribute land held by the Baltic German nobility. While they purportedly had no significant connection with foreign fascist movements, the organisation advocated a more authoritarian and nationalist government in Estonia.[5][6] The organisation had welcomed Hitler's rise to power, even though they later tried to distance themselves from Nazism.[7] The league rejected racial ideology and openly criticized the Nazi persecution of Jews[4] and also lacked the willingness to use violence or the goal of territorial expansion.[8] They also wore a black beret as their uniform headgear, and used the Roman salute. Moderate members of the movement such as Johan Pitka gradually left the organisation and new members were allowed to join, who were not veterans. The organisation issued its own newspaper, Võitlus ('The Struggle').

The movement strongly supported constitutional reform that would enable a strong president to address national problems. Estonian patriots had been advocating such a change since the mid 20s, but it was not until October 1933 that the government was forced to allow the Vaps movement to put forward its own referendum on constitutional reform, after watered down centre-right proposals failed to win any support.[9] This was approved by 72.7 percent of the voters.[2] The organization was banned by the government of Jaan Tõnisson (who opposed the constitutional reform) under a state of emergency imposed before the referendum, but after this the organization was re-established and became even more radically patriotic. The league spearheaded replacement of the parliamentary system with a presidential form of government and laid the groundwork for an April 1934 presidential election, which it expected to win.

After the League won absolute majorities in local elections in the three largest cities at the beginning of 1934, but not in the most rural self-governments nor small towns and boroughs, the recently elected constitutional "State Elder" (head of government and head of state) Konstantin Päts declared a state of emergency in the whole country (in certain parts, this was already in effect since 1918) on 12 March 1934, disbanding the Vaps movement and arresting its leading figures. Konstantin Päts established a regime that the historian Georg von Rauch has called "Authoritarian Democracy". In 1935, a National Association was formed to replace political parties and series of state corporate institutions were introduced.[5]

The league was banned and disbanded in December 1935. On 6 May 1936, 150 members of the league went on trial; 143 of them were convicted and sentenced to lengthy terms of imprisonment. They were granted an amnesty and freed in 1938, by which time the league had lost most of its popular support. By 1 January 1938, a new constitution took effect and new parliament was elected in February 1938.[10][11] The new constitution combined a strong President with a partly elected and partly appointed, officially non-partisan Parliament.[5]

The movement maintained good relations with Finnish nationalist movements such as the Lapua Movement, Patriotic People's Movement and Academic Karelia Society.[4]

As of 2019, the Vaps movement has no known active members. In 2009, Jüri Liim reportedly submitted a formal application to restore the organisation the original Vaps Movement.[12] The application was not successful, and the Vaps Movement has not been legalised in Estonia.[13]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Kasekamp, Andres (3 June 2000). The Radical Right in Interwar Estonia. ISBN 9780312225988. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Vaps". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ Conclusions of Estonian International Commission for Investigation of Crimes Against Humanity Archived 29 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Kasekamp, Andres (3 June 2000). The Radical Right in Interwar Estonia. ISBN 9780312225988. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d A History of Fascism, 1914-1945 By Stanley George Payne ISBN 1-85728-595-6

- ^ T. Parming, The Collapse of Liberal Democracy and the Rise of Authoritarianism in Estonia, London, 1975

- ^ "Ajaloolane: ka vapsid ise pidasid end fašistideks" Postimees, 18. august 2017

- ^ Marandi, Rein "Must-valge lipu all : Vabadussõjalaste liikumine Eestis 1929-1937. 1. Legaalne periood (1929-1934)" Stockholm : Centre for Baltic Studies at the University of Stockholm, 1991

- ^ Andres Kasekamp, "Fascism by Popular Initiative: The Rise and Fall of the Vaps Movement in Estonia", Journal of Comparative Fascist Studies (voeventl 4), pp. 157–158

- ^ S. Payne, A history of Fascism, 1914-1945, Routledge, 1995

- ^ Eesti Vabariigi arengulugu aastatel 1918–1940

- ^ Postimees 15 April 2009 22:27: Jüri Liim taastab vapsiliikumise

- ^ "Vabadussõjalaste Keskliit jätkab tegevust ajaloolise nimega". Postimees. 7 July 2009. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- Andres Kasekamp. 2000. The Radical Right in Interwar Estonia. London: Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 0-312-22598-9

- Varrak, Toomas (2000). "Estonia: Crisis and 'Pre-Emptive Authoritarianism". In Berg-Schlosser, Dirk; Jeremy Mitchell (eds.). Conditions of democracy in Europe, 1919-39: systematic case-studies. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 109–128. ISBN 0-312-22843-0.

External links[]

- 1929 establishments in Estonia

- 1930s disestablishments in Estonia

- Anti-communism in Estonia

- Anti-communist organizations

- Banned far-right parties

- Defunct political parties in Estonia

- Estonian nationalism

- Political history of Estonia

- Veterans' organizations

- Political parties established in 1929

- Political parties disestablished in 1934

- Right-wing populism in Estonia