Zimbabwe Rhodesia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2012) |

Zimbabwe Rhodesia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | |||||||||

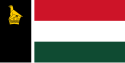

Flag

Coat of arms

| |||||||||

| Motto: Sit Nomine Digna (Latin) "May it be worthy of the name" | |||||||||

| Anthem: "Rise, O Voices of Rhodesia" | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Status | Unrecognised state | ||||||||

| Capital | Salisbury | ||||||||

| Common languages | English (official) Shona Sindebele Afrikaans | ||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Rhodesian | ||||||||

| Government | Parliamentary republic | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

• 1979 | Josiah Zion Gumede | ||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||

• 1979 | Abel Muzorewa | ||||||||

| Historical era | Cold War | ||||||||

| 1 June 1979 | |||||||||

| 11 December 1979 | |||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 1979 | 390,580 km2 (150,800 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1979 | 6,930,000 | ||||||||

| Currency | Rhodesian dollar | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Zimbabwe | ||||||||

Zimbabwe Rhodesia (/zɪmˈbɑːbweɪ roʊˈdiːʒə/) was an unrecognised state that existed from 1 June 1979 to 11 December 1979. Zimbabwe Rhodesia was preceded by an unrecognised republic named Rhodesia and was briefly followed by the re-established British colony of Southern Rhodesia, which according to British constitutional theory had remained the lawful government in the area after Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) in 1965. About three months later, the re-established colony of Southern Rhodesia was granted internationally recognized independence within the Commonwealth as the Republic of Zimbabwe.

Under pressure from the international community to satisfy the civil rights movement by black people in Rhodesia, an "Internal Settlement" was drawn up between the Smith administration of Rhodesia and moderate African nationalist parties not involved in armed resistance. Meanwhile, the government continued to battle armed resistance from both Soviet- and Chinese-backed insurgents it referred to as terrorists. The Rhodesian Bush War was an extension of the Cold War, being a proxy conflict between the West and East, similar to those in Vietnam and Korea.

The "Internal Settlement" agreement led to relaxation of education, property and income qualifications for voter rolls, resulting in the first ever black-majority electorate. The country's civil service, judiciary, police and armed forces continued to be administered by the same officials as before, of whom most were white people, due to the composition of the upper-middle class of the period.[2]

Despite these changes, the new state did not gain international recognition, with the Commonwealth claiming that the "so-called 'Constitution of Zimbabwe Rhodesia'" would be "no more legal and valid" than the UDI constitution it replaced.[3]

Nomenclature[]

As early as 1960, African nationalist political organisations in Rhodesia agreed that the country should use the name "Zimbabwe"; they used that name as part of the titles of their organisations. The name "Zimbabwe", broken down to Dzimba dzamabwe in Shona (one of the two major languages in the country), means "houses of stone". Meanwhile, the white Rhodesian community was reluctant to drop the name "Rhodesia", hence a compromise was met.[4]

The Constitution named the new state simply as "Zimbabwe Rhodesia", with no reference to its status as a republic in its name.[5] As such, it was similar in style to post-1994 South Africa renaming the Natal province as "KwaZulu-Natal". Although the official name contained no hyphen, the country's name was hyphenated in some foreign publications as "Zimbabwe-Rhodesia".[6][7][8][9] The country was also nicknamed "Rhobabwe", a blend of "Rhodesia" and "Zimbabwe".[10][11]

After taking office as Prime Minister, Abel Muzorewa sought to drop "Rhodesia" from the country's name.[12] The name "Zimbabwe Rhodesia" had been criticised by some black politicians like Senator Chief Zephaniah Charumbira, who said it implied that Zimbabwe was "the son of Rhodesia".[13] ZANU PF, led by Robert Mugabe in exile, denounced what it described as "the derogatory name of 'Zimbabwe Rhodesia'".[14]

The government also adopted a new national flag, featuring the same Zimbabwe soapstone bird, on 2 September of that year.[15] In addition, it announced changes to public holidays, with Rhodes Day and Founders Day being replaced by two new holidays, both of which were known as Ancestors Day, while Republic Day and Independence Day were to be replaced by President's Day and Unity Day, celebrated on 25 and 26 October of that year.[16]

In response, the Voice of Zimbabwe radio service operated by Robert Mugabe's ZANU-PF from Maputo in Mozambique, carried a commentary entitled "The proof of independence is not flags or names", dismissing the changes as aimed at "strengthening the racist puppet alliance's position at the Zimbabwe conference in London".[17]

The national airline, Air Rhodesia, was also renamed Air Zimbabwe.[18] However, no postage stamps were issued; issues of 1978 still used "Rhodesia", and the next stamp issues were in 1980, after the change to just "Zimbabwe," and were inscribed accordingly.[19]

Government of Zimbabwe Rhodesia[]

During its brief existence, Zimbabwe Rhodesia had one election, which resulted in its short-lived biracial government.

Constitution[]

Adapting the constitution of the Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI), Zimbabwe Rhodesia was governed by a Prime Minister and Cabinet chosen from the majority party in a 100-member House of Assembly. A 40-member Senate acted as the upper House, and both together chose a figurehead President in whose name the government was conducted.

Legislative branch[]

House of Assembly[]

Of the 100 members of the House of Assembly, 72 were "common roll" members for whom the electorate was every adult citizen. All of these members were black Africans. Those on the previous electoral roll of Rhodesia (due to education, property and income qualifications for voter rolls, mostly but not only white constituencies) elected 20 members; although this did not actually exclude non-whites, very few black Africans met the qualification requirements. A delimitation commission sat in 1978 to determine how to reduce the previous 50 constituencies to 20. The remaining eight seats for old voter role non-constituency members were filled by members chosen by the other 92 members of the House of Assembly once their election was complete. In the only election held by Zimbabwe Rhodesia, Bishop Abel Muzorewa's United African National Council (UANC) won a majority in the common-roll seats, while Ian Smith's Rhodesian Front (RF) won all of the old voter roll seats. Ndabaningi Sithole's Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) won 12 seats.

Senate[]

The Senate of Zimbabwe Rhodesia had 40 members. Ten members each were returned by the old voter roll members of the House of Assembly and the common roll members, and five members each by the Council of Chiefs of Mashonaland and Matabeleland. The remaining members were directly appointed by the President under the advice of the Prime Minister. While the House of Assembly had changed greatly to be nearly in line with modern ideals of universal suffrage, the Senate remained dominated by the former political stalwarts, effectively allowing a check on the new House.

Executive branch[]

President[]

The President of Zimbabwe Rhodesia was elected by the members of the Parliament, sitting together. At the election on 28 May 1979, Josiah Zion Gumede of the United African National Council (UANC)[20] and Timoth Ndhlovu of the United National Federal Party (UNFP) were nominated.[21] Gumede won by 80 votes to Ndhlovu's 33.[22]

Prime Minister[]

Starting with 51 seats out of 100, Abel Muzorewa of the UANC was appointed as Prime Minister, and also appointed Minister Combined Operations and Defence.[23] He formed a joint government with Ian Smith, the former Prime Minister of Rhodesia, who was a Minister without Portfolio.[24] Muzorewa also attempted to include the other African parties who had lost the election. Rhodesian Front members served as Muzorewa's ministers of justice, agriculture, and finance, with David Smith continuing in the role of Minister of Finance, while P. K. van der Byl, the hardline former Minister of Defence, serving as both Minister of Transport and Minister of Power and Posts.[23]

End of Zimbabwe Rhodesia[]

The Lancaster House Agreement stipulated that control over the country be returned to the United Kingdom in preparation for elections to be held in the spring of 1980. Accordingly, on 11 December 1979, the Constitution of Zimbabwe Rhodesia (Amendment) (No. 4) Act, declaring that "Zimbabwe Rhodesia shall cease to be an independent State and become part of Her Majesty's dominions", was passed.[25]

In response, the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed the Southern Rhodesia Constitution (Interim Provisions) Order 1979, establishing the offices of Governor and Deputy Governor of Southern Rhodesia, filled by Lord Soames and Sir Antony Duff respectively.[26]

Although the name of the country formally reverted to Southern Rhodesia at this time, the name "Zimbabwe Rhodesia" remained in many of the country's institutions, such as the Zimbabwe Rhodesia Broadcasting Corporation.[27] On 18 April 1980, Southern Rhodesia became the independent Republic of Zimbabwe.

Gallery[]

Flag of Zimbabwe Rhodesia (1 June 1979 – 1 September 1979)

Flag of Zimbabwe Rhodesia (2 September 1979 – 11 December 1979)

Coat of arms of Zimbabwe Rhodesia

See also[]

- Colonial history of Southern Rhodesia

- Education in Zimbabwe

- Rhodesian Bush War

- History of Zimbabwe

- Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland

- Colony of Southern Rhodesia

- Rhodesia

- Republic of Zimbabwe

References[]

- ^ Section 6 of the Constitution of Zimbabwe Rhodesia, 1979: "There shall be a President in and over Zimbabwe Rhodesia who shall be Commander-in-Chief of the Defence Forces of Zimbabwe Rhodesia." Quoted in The Struggle for Independence: Doc. 696-899 (February-September 1979) Archived 20 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Inst. für Afrikakunde, 1984, page 921

- ^ Will We Destroy Zimbabwe-Rhodesia? Archived 11 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Sarasota Journal, July 18, 1979, page 4

- ^ An Analysis of the Illegal Regime's "Constitution for Zimbabwe Rhodesia" Archived 21 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Commonwealth Secretariat, 1979, page 2

- ^ A Concise Encyclopedia of Zimbabwe Archived 24 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Donatus Bonde, Mambo Press, 1988 page 422

- ^ "Constitution of Zimbabwe Rhodesia, 1979" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 February 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ Editorials on File, Volume 10, Issue 2, Facts on File, Incorporated, 1979, pages 873-877

- ^ Congressional Quarterly Weekly Report, Volume 37, Congressional Quarterly, Incorporated, 1979, page 1585

- ^ African Leaders United On View Of Zimbabwe-Rhodesia Archived 10 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Toledo Blade, June 24, 1979

- ^ Zimbabwe-Rhodesia Plagued By Trouble Archived 10 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Reading Eagle, June 14, 1979

- ^ Under The Skin: The Death of White Rhodesia, David Caute, Northwestern University Press, 1983, page 354

- ^ Confusion in Rhobabwe Archived 15 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The Spectator 20 May 1978

- ^ Zimbabwe Rhodesia Bids To Shorten Name To Zimbabwe Archived 10 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Lakeland Ledger, August 26, 1979

- ^ Pioneers, Settlers, Aliens, Exiles: The Decolonisation of White Identity in Zimbabwe Archived 23 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine, J. L. Fisher, ANU E Press, 2010, page 58

- ^ Zimbabwe News, Volumes 11-16, Central Bureau of Information of the Zimbabwe National Union, 1979, page 2

- ^ NEW FLAG RAISING CEREMONY IN SALISBURY, Associated Press Archive, 4 September 1979

- ^ Summary of World Broadcasts: Non-Arab Africa Archived 15 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Issues 6208-6259, BBC Monitoring Service, 1979

- ^ Summary of World Broadcasts: Non-Arab Africa Archived 30 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Issues 6208-6259, BBC Monitoring Service, 1979

- ^ Africa Calls from Zimbabwe Rhodesia Archived 15 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Issues 115-125, 1979, page 33

- ^ Summary of World Broadcasts: Non-Arab Africa Archived 15 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Issues 6308-6358, BBC Monitoring Service, 1980

- ^ Library of Congress Foreign Affairs and National Defense Division, United States Congress. Chronologies of Major Developments in Selected Areas of Foreign Affairs.

- ^ Sub-Saharan Africa Report Archived 24 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Issues 2114-2120, page 5278, 1979

- ^ Africa Research Bulletin Archived 24 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Blackwell, 1979, page 5278

- ^ Jump up to: a b Muzorewa Names a Cabinet, Reserving Key Roles for Himself and Smith Archived 24 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine, New York Times, May 31, 1979

- ^ Zimbabwe-Rhodesia Attacks Guerrilla Positions in Zambia Archived 3 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Washington Post, June 27, 1979

- ^ Collective Responses to Illegal Acts in International Law: United Nations Action in the Question of Southern Rhodesia, Vera Gowlland-Debbas Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1990, page 91

- ^ Southern Rhodesia Constitution (Interim Provisions) Order 1979 Archived 21 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Hansard, 14 December 1979

- ^ ZIMBABWE BILL Archived 15 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine, HL Deb 17 December 1979 vol 403 cc1470-514

External links[]

Media related to Southern Rhodesia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Southern Rhodesia at Wikimedia Commons

- Rhodesia

- 1970s disestablishments in Rhodesia

- 1970s in Rhodesia

- 1979 disestablishments in Africa

- 1979 establishments in Rhodesia

- English-speaking countries and territories

- Former countries in Africa

- Former polities of the Cold War

- Former republics

- Former unrecognized countries

- History of Rhodesia

- History of Zimbabwe

- Provisional governments

- States and territories disestablished in 1979

- States and territories established in 1979

- Zimbabwe and the Commonwealth of Nations

- Former countries