2021 Atlantic hurricane season

| 2021 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | May 22, 2021 |

| Last system dissipated | November 7, 2021 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Sam[nb 1] |

| • Maximum winds | 155 mph (250 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 929 mbar (hPa; 27.43 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 21 |

| Total storms | 21 |

| Hurricanes | 7 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 4 |

| Total fatalities | 161 total |

| Total damage | $80.543 billion (2021 USD) (Third-costliest tropical cyclone season on record) |

| Related articles | |

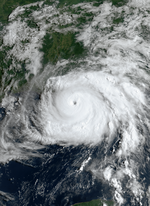

The 2021 Atlantic hurricane season was the third-most active Atlantic hurricane season on record, producing 21 named storms; it was also the second season in a row after 2020, and third overall, in which the designated 21-name list of storm names was exhausted.[1][2] It was also the sixth consecutive year in which there was above-average tropical cyclone activity.[nb 2][1] Additionally, with a damage total of more than $80 billion, it was the third-costliest season on record behind 2005 and 2017. The season began on June 1, 2021, and ended on November 30, 2021. These dates, adopted by convention, historically describe the period in each year when most Atlantic tropical cyclones form.[4] However, subtropical or tropical cyclogenesis is possible at any time of the year, as was the case this season, when Tropical Storm Ana formed on May 22, making 2021 the seventh consecutive year that a storm formed before the designated start of the season.[5] The season had the most active June on record, tying 1886, 1909, 1936, and 1968 with three named storms forming in the month.[6] Then, on July 1, Hurricane Elsa formed, surpassing 2020's Tropical Storm Edouard as the earliest-forming fifth named storm on record by five days.[7] Elsa caused significant impacts from Barbados to much of the East Coast of the United States, and was one of four billion-dollar storms in the season.[8]

In addition to Elsa, several hurricanes had severe impact on land in 2021. Hurricane Grace intensified to a Category 3 major hurricane[nb 3] before making landfall in the Mexican state of Veracruz. Hurricane Ida was a deadly and destructive hurricane that made landfall in the U.S. state of Louisiana at Category 4 strength, becoming the most intense and destructive tropical cyclone to affect the state since Hurricane Katrina; it also caused catastrophic flooding across the Northeastern United States. By September, Hurricane Larry peaked as a powerful Category 3 hurricane over the open Atlantic before making landfall in the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador as a Category 1 hurricane. Later in the month, Hurricane Nicholas moved erratically both on- and offshore the coasts of Texas and Louisiana.

This season, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) began issuing regular Tropical Weather Outlooks on May 15, two weeks earlier than it has done in the past. The change was implemented given that named systems had formed in the Atlantic Ocean prior to the start of the season in each of the preceding six cycles.[9] Prior to the start of the season, NOAA deployed five modified hurricane-class saildrones at key locations around the basin, and in September, one of the vessels was in position to obtain video and data from inside Hurricane Sam. It was the first ever research vessel to venture inside the middle of a major hurricane.[10]

Seasonal forecasts[]

| Source | Date | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes |

Ref |

| Average (1991–2020) | 14.4 | 7.2 | 3.2 | [3] | |

| Record high activity | 30 | 15 | 7† | [11] | |

| Record low activity | 4 | 2† | 0† | [11] | |

| ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– | |||||

| TSR | December 9, 2020 | 16 | 7 | 3 | [12] |

| CSU | April 8, 2021 | 17 | 8 | 4 | [13] |

| PSU | April 8, 2021 | 9–15 | n/a | n/a | [14] |

| TSR | April 13, 2021 | 17 | 8 | 3 | [15] |

| UA | April 13, 2021 | 18 | 8 | 4 | [16] |

| NCSU | April 14, 2021 | 15–18 | 7–9 | 2–3 | [17] |

| TWC | April 15, 2021 | 18 | 8 | 3 | [18] |

| TWC | May 13, 2021 | 19 | 8 | 4 | [19] |

| NOAA | May 20, 2021 | 13–20 | 6–10 | 3–5 | [20] |

| UKMO* | May 20, 2021 | 14 | 7 | 3 | [21] |

| TSR | May 27, 2021 | 18 | 9 | 4 | [22] |

| CSU | June 3, 2021 | 18 | 8 | 4 | [23] |

| UA | June 16, 2021 | 19 | 6 | 4 | [24] |

| TSR | July 6, 2021 | 20 | 9 | 4 | [25] |

| CSU | July 8, 2021 | 20 | 9 | 4 | [26] |

| UKMO* | August 2, 2021 | 15 | 6 | 3 | [27] |

| NOAA | August 4, 2021 | 15–21 | 7–10 | 3–5 | [28] |

| CSU | August 5, 2021 | 18 | 8 | 4 | [29] |

| TSR | August 5, 2021 | 18 | 7 | 3 | [30] |

| ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– | |||||

| Actual activity |

21 | 7 | 4 | ||

| * June–November only † Most recent of several such occurrences. (See all) | |||||

In advance of, and during, each hurricane season, several forecasts of hurricane activity are issued by national meteorological services, scientific agencies, and noted hurricane experts. These include forecasters from the United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)'s Climate Prediction Center, Tropical Storm Risk (TSR), the United Kingdom's Met Office (UKMO), and Philip J. Klotzbach, William M. Gray and their associates at Colorado State University (CSU). The forecasts include weekly and monthly changes in significant factors that help determine the number of tropical storms, hurricanes, and major hurricanes within a particular year. According to NOAA and CSU, the average Atlantic hurricane season between 1991 and 2020 contained roughly 14 tropical storms, seven hurricanes, three major hurricanes, and an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) index of 72–111 units.[12] Broadly speaking, ACE is a measure of the power of a tropical or subtropical storm multiplied by the length of time it existed. It is only calculated for full advisories on specific tropical and subtropical systems reaching or exceeding wind speeds of 39 mph (63 km/h).[3] NOAA typically categorizes a season as above-average, average, or below-average based on the cumulative ACE index, but the number of tropical storms, hurricanes, and major hurricanes within a hurricane season is sometimes also considered.[3]

Pre-season forecasts[]

On December 9, 2020, TSR issued an extended range forecast for the 2021 hurricane season, predicting slightly above-average activity with 16 named storms, seven hurricanes, three major hurricanes, and an ACE index of about 127 units. TSR cited the expected development of a weak La Niña during the third quarter of 2021 as the main factor behind their forecast.[12] CSU released their first predictions on April 8, 2021, predicting an above-average season with 17 named storms, eight hurricanes, four major hurricanes, and an ACE index of 150 units, citing the unlikelihood of an El Niño and much warmer than average sea surface temperatures in the subtropical Atlantic.[13] TSR updated their forecast on April 13, with 17 named storms, eight hurricanes, and three major hurricanes, with an ACE index of 134 units.[15] On the same day, University of Arizona (UA) issued its seasonal prediction of above-average hurricane activities, with 18 named storms, eight hurricanes, four major hurricanes, and an ACE index of 137 units.[16] North Carolina State University (NCSU) made its prediction for the season on April 14, calling for an above-average season with 15 to 18 named storms, seven to nine hurricanes, and two to three major hurricanes.[17] On May 13, The Weather Company (TWC) updated their forecast for the season, calling for an active season, with 19 named storms, eight hurricanes, and four major hurricanes.[19] On May 20, NOAA's Climate Prediction Center issued their forecasts for the season, predicting a 60% chance of above-average activity and 30% chance for below-average activity, with 13-20 named storms, 6-10 hurricanes and 3-5 major hurricanes.[20] The following day, UKMO issued their own forecast for the 2021 season, predicting an average one with 14 named storms, seven hurricanes, and three major hurricanes, with a 70% chance that each of these statistics will fall between 9 and 19, 4 and 10, and 1 and 5, respectively.[21]

Mid-season forecasts[]

On June 16, UA updated their forecast for the season, with 19 named storms, six hurricanes, four major hurricanes, and an ACE index of 183 units.[24] On July 6, TSR released their third forecast for the season, slightly increasing their numbers to 20 named storms, 9 hurricanes and 4 major hurricanes. This prediction was largely based on their expectation for a weak La Niña to develop by the third quarter of the year.[25] On July 8, CSU updated their prediction to 20 named storms, 9 hurricanes, and 4 major hurricanes.[26] On August 5, TSR issued their final forecast for the season, lowering their numbers to 18 named storms, 7 hurricanes and 3 major hurricanes.[30]

Seasonal summary[]

Tropical Storm Ana formed ten days before the official start of the 2021 Atlantic hurricane season, making 2021 the seventh consecutive year in which a tropical or subtropical cyclone formed before the season's official start on June 1. Ana formed in a location where no tropical storms within the month of May had been documented since before 1950.[31] In mid-June, a rapidly developing non-tropical low offshore of the North Carolina coast became Tropical Storm Bill. The system lasted for only two days before becoming extratropical. Later that month, Tropical Storm Claudette formed on the coast of Louisiana and Tropical Storm Danny formed off the coast of South Carolina. Hurricane Elsa formed at the beginning of July and became the first hurricane of the season on July 2 before impacting the Caribbean and later the Eastern United States and Atlantic Canada after making landfall in Florida as a tropical storm on July 8. Afterwards, activity came to a halt due to unfavorable conditions across the basin.

On August 11, Fred formed in the eastern Caribbean, bringing impacts to the Greater and Lesser Antilles, and the Southeastern United States. A couple of days later, Grace formed and strengthened to the second hurricane and first major hurricane of the season, and brought impacts to Hispaniola, the Yucatan Peninsula, and eastern Mexico. A third tropical system, Henri, developed on August 16, near Bermuda.[32] Henri meandered for several days before becoming the third hurricane of the season on August 21 and impacted New England, causing record flooding in some places. Towards the end of the month, Hurricane Ida formed, causing major damage in Western Cuba before rapidly intensifying into a Category 4 hurricane and striking Southeastern Louisiana at near peak intensity, producing widespread, catastrophic damage. Its remnants then generated a deadly tornado outbreak and widespread flooding across the Northeastern United States. Two other tropical storms, Kate and Julian, also formed briefly during this time, but remained at sea. Larry initially formed on the last day of August and strengthened into a major hurricane early in September. It became the first hurricane to make landfall on Newfoundland since Igor in 2010.[33]

| Rank | Cost | Season |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ≥ $294.703 billion | 2017 |

| 2 | $172.297 billion | 2005 |

| 3 | ≥ $80.543 billion | 2021 |

| 4 | $72.341 billion | 2012 |

| 5 | $61.148 billion | 2004 |

| 6 | ≥ $51.146 billion | 2020 |

| 7 | ≥ $50.126 billion | 2018 |

| 8 | ≥ $48.855 billion | 2008 |

| 9 | $27.302 billion | 1992 |

| 10 | ≥ $17.485 billion | 2016 |

As the mid-point of the hurricane season approached,[nb 4] Tropical Storm Mindy formed on September 8, and made landfall on the Florida Panhandle shortly thereafter.[34] It was followed by Hurricane Nicholas, which formed on September 12,[35] and made landfall along the central Texas coast two days later.[36] They were followed by three tropical storms—Odette, Peter, and Rose—which were steered by prevailing winds away from any interaction with land.[37] The busy pace of storm-formation continued late into September. Sam, a long-lived major hurricane, developed in the central tropical Atlantic, and proceeded to rapidly intensify from a tropical depression to a hurricane within 24 hours on September 23 and 24.[38][39] Meanwhile, Subtropical Storm Teresa formed north of Bermuda on September 24. Short-lived Tropical Storm Victor formed late in the month at an unusually low latitude of 8.3°N; only two North Atlantic tropical storms on record have formed further to the south: 2018's Kirk at 8.1°N, and an unnamed 1902 hurricane at 7.7°N.[40]

After a nearly four-week break from tropical activity, Subtropical Storm Wanda formed in the central North Atlantic on October 31, and became fully tropical on November 1. This system was the same storm that previously had brought rain and damaging wind gusts to Southern New England as a potent nor'easter.[41]

The ACE index for the 2021 Atlantic hurricane season, as calculated by Colorado State University using data from the NHC, is 145.1 units.[42] The totals represent the sum of the squares for every (sub)tropical storm's intensity of over 33 knots (38 mph; 61 km/h), divided by 10,000.

Systems[]

Tropical Storm Ana[]

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | May 22 – May 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) 1004 mbar (hPa) |

An upper-level trough drifted across the western Atlantic on May 19, inducing the formation of a low-pressure area along a stalled front the next day. That extratropical cyclone became co-located with an upper-level low, which afforded the system lower wind shear and sufficient instability to develop convection despite cold ocean waters. After the system shed its frontal structure, it became Subtropical Storm Ana at 06:00 UTC on May 22. The system made a counter-clockwise loop due to weak steering currents. With the presence of a more symmetrical wind field and organized thunderstorm activity by early on May 23, Ana transitioned into a tropical storm as it accelerated northeastward amid southwesterly mid-level flow. Ana reached peak winds of 45 mph (75 km/h) before it encountered increasing wind shear and began losing convection. By 18:00 UTC on May 23, the system transitioned into an extratropical cyclone, which merged with a trough early on May 24. That trough was then absorbed by a frontal system later that day.[43]

Tropical Storm Bill[]

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 14 – June 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) 992 mbar (hPa) |

In mid-June, a cold front sagged southward across the Mid-Atlantic United States. Shower and thunderstorm activity coalesced offshore South Carolina, leading to the formation of an area of low pressure there. This low, and the associated convection, became better defined while being directed northeast by a shortwave trough, and a tropical depression formed about 125 mi (200 km) east-southeast of Cape Fear, North Carolina, around 06:00 UTC on June 14. Though sheared, the incipient cyclone strengthened into Tropical Storm Bill twelve hours later. Banding features became better defined, especially across the northern and western quadrants of the storm, and Bill reached peak winds of 65 mph (100 km/h) early on June 15 while paralleling the Northeast United States coastline. Its northeast track soon brought the system over colder waters and into higher wind shear, resulting in Bill's transition to an extratropical cyclone approximately 370 mi (595 km) east-southeast of Halifax, Nova Scotia, around 00:00 UTC on June 16. The low dissipated into a trough six hours later before progressing across southeastern Newfoundland.[44]

Tropical Storm Claudette[]

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 19 – June 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) 1003 mbar (hPa) |

In mid-June, a tropical wave crossed the Caribbean and eventually interacted with the enhanced portion of the monsoon trough in the East Pacific. This resulted in a large cyclonic gyre over Central America, with distinct disturbances over the East Pacific and in the Bay of Campeche. The latter system moved north. Though it struggled with wind shear, resulting in a broad center with multiple swirls and winds largely confined in a rainband to the east, the system organized into Tropical Storm Claudette around 00:00 UTC on June 19. It promptly moved onshore about 30 mi (50 km) south-southwest of Houma, Louisiana, with peak winds of 45 mph (75 km/h). The cyclone weakened to a depression as it moved northeastward over Alabama, but it regained tropical storm intensity while crossing North Carolina and reached a secondary peak intensity just offshore. By June 22, Claudette was accelerating northeast and undergoing extratropical transition, a process it completed around 06:00 UTC that day. The extretropical low dissipated on June 23 to the southeast of Nova Scotia.[45]

Heavy rainfall and tropical storm-force winds were reported across much of the Southeastern United States.[46] Several tornadoes were spawned by Claudette, including an EF2 tornado that caused major damage and injured 20 people in East Brewton, Alabama.[47][48] The system caused 14 fatalities, all in Alabama.[49]

Tropical Storm Danny[]

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 27 – June 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) 1009 mbar (hPa) |

On June 22, an upper-level trough detached from the mid-latitude jet stream. The system transitioned into an upper-level low over the subtropical central Atlantic during the next few days while trekking southwestward. Warmer waters caused convective activity to increase on June 24 while a deep-layer ridge moved the system westward.[50] The NHC soon began monitoring the disturbance for development as it passed well south of Bermuda.[51] By June 27, the trough developed a closed low-level circulation as it continued to track west-northwestward, and it is estimated that Tropical Depression Four formed by 18:00 UTC that day while centered about 460 mi (740 km) east-southeast of Charleston, South Carolina. Appropriately 12 hours later, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Danny. The storm intensified slightly further a few hours later and reached its peak intensity just offshore South Carolina with sustained winds of 45 mph (75 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 1009 mb (29.80 inHg). At 23:20 UTC on June 28, Danny made landfall just north of Hilton Head on Pritchards Island, South Carolina, with sustained winds of 40 mph (65 km/h).[50] Danny was the first storm to make landfall in the state of South Carolina in the month of June since 1867.[52] The cyclone rapidly weakened while moving inland, weakening to a tropical depression just 40 minutes later.[50] Danny dissipated over eastern Georgia early on June 29, after satellite imagery revealed that its low-level circulation was no longer well defined.[53]

Danny produced rainfall totals of up to 3 inches (76.2 mm) in parts of South Carolina in the matter of hours following landfall, causing minor flash floods in populated areas.[54] Lightning resulted in damage to some structures, while some trees were downed in Savannah, Georgia, by windy conditions.[55] Danny produced heavy rainfall across portions of Metro Atlanta as it tracked across Georgia in a westwardly direction.[56] Overall, the storm caused only about $5,000 in damage.[57]

Hurricane Elsa[]

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 1 – July 9 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min) 991 mbar (hPa) |

The NHC began to monitor a tropical wave about 800 miles (1,300 km) from Cape Verde at 12:00 UTC on June 29.[58] The wave quickly organized as it moved eastward,[59] and advisories were issued on Potential Tropical Cyclone Five at 21:00 UTC on June 30, since scatterometer data depicted an elongated and ill-defined circulation.[60] It became a tropical depression by 03:00 UTC on July 1 as its satellite appearance continued to gradually improve, with prominent banding features to the west of its center. By 09:00 UTC that same day, the depression further intensified into a tropical storm, and the NHC assigned it the name Elsa. This also made Elsa the earliest fifth-named storm on record, surpassing the previous record held by Tropical Storm Edouard of the previous year, which formed on July 6.[61] Elsa slowly strengthened overnight as it accelerated westward,[61][62] and at 10:45 UTC on July 2, the NHC upgraded Elsa to a Category 1 hurricane.[63] At 15:00 UTC on July 3, the system weakened back into a tropical storm due to northeasterly wind shear which was partially due to the storm's rapid forward motion at almost 30 mph (48 km/h).[64] Elsa's forward motion significantly slowed down to 14 mph (22 km/h) by the next day, as the storm's center relocated to the east under the region with the strongest convection while passing just north of Jamaica.[65][66] At 18:00 UTC on July 5, Elsa made landfall on west-central Cuba and weakened slightly.[67] Several hours later, at 02:00 UTC on July 6, Elsa emerged into the Gulf of Mexico and began to re-strengthen.[68] At 00:00 UTC on July 7, Elsa re-strengthened into a Category 1 hurricane, with winds of 75 mph (120 km/h).[69][70] However, several hours later, wind shear and an entrainment of dry air caused Elsa to weaken back into a tropical storm.[71][72] Elsa continued moving northward, and at 15:00 UTC (8:00 a.m. EDT), Elsa made landfall in Taylor County, Florida.[73][74] The storm weakened after landfall, but remained at minimal tropical storm strength as part of its circulation remained over water.[75] Afterward, Elsa gradually began accelerating northeastward, and re-intensified due to baroclinic forcing.[76] Elsa became a post-tropical cyclone at 18:00 UTC on July 9 over eastern Massachusetts.[77]

In Barbados, the storm brought down trees, damaged roofs, caused widespread power outages, and caused flash flooding. In the U.S., one person was killed by a falling tree in Florida, and another seventeen were injured at a Georgia military base during an EF1 tornado.[78] At least five people were killed by Elsa, including four in the Caribbean and one in the United States. The storm caused at least $1.2 billion in damages.[79][80]

Tropical Storm Fred[]

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 11 – August 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) 991 mbar (hPa) |

Three tropical waves emerged into the Atlantic from the west coast of Africa in late July and early August. The waves slowly consolidated and organized while moving generally west-northwestward across the Atlantic. The system passed through the Leeward Islands without a well-defined center on August 10. By 00:00 UTC the next day, however, the system developed into Tropical Storm Fred over the northeastern Caribbean just south of Puerto Rico. Fred then made landfall near San Cristóbal, Dominican Republic, with winds of 45 mph (75 km/h) at 17:00 UTC. The storm deteriorated to a tropical depression early on August 12, hours before emerging into the Atlantic off the north coast of Haiti. Fred briefly re-intensified into a tropical storm on August 13, but strong wind shear weakened it back to a tropical depression before striking Cayo Romano, Cuba, at 12:00 UTC. Land interaction then caused the system to degenerate into an open trough early on October 14, but the storm began re-organizing after emerging into the Gulf of Mexico several hours later. Fred regenerated into a tropical storm over the eastern Gulf of Mexico around 12:00 UTC the next day as it headed generally northward. At 18:00 UTC on August 16, Fred peaked with winds of 65 mph (100 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 993 mbar (29.32 inHg), just over an hour before making landfall near Cape San Blas, Florida. Fred weakened to a tropical depression over Alabama on August 17, before degenerating into a remnant low over Tennessee at 00:00 UTC on August 18. The remnant low became extratropical about 24 hours later over Pennsylvania. This system persisted until dissipating over Massachusetts on August 20.[81]

Several islands of the Lesser Antilles reported rainfall and gusty winds.[81] Similar conditions in Puerto Rico resulted in over 13,000 customers losing electricity.[82] In the Dominican Republic, Fred left approximately 500,000 people without electricity and 40,000 customers without power. Floods isolated 47 communities and damaged or demolished more than 800 homes, including about 100 in Santo Domingo. The storm produced heavy rains over parts of Cuba, including a maximum total of 11.25 in (286 mm) of precipitation at Hatibonico in Guantánamo Province. In Florida, storm surge caused minor coastal flooding in the Forgotten Coast region. About 40,000 customers lost electricity throughout northern Florida. One person died from a car accident due to hydroplaning in Bay County. Fred and its remnants later spawned 31 tornadoes from Georgia to Massachusetts. The storm also caused flooding as it moved farther inland, especially over western North Carolina. At least 784 businesses and homes and 23 bridges in Buncombe and Haywood counties combined were damaged or destroyed. The town of Cruso alone reported six fatalities and about $300 million in damage. Throughout the United States, Fred left seven deaths and approximately $1.3 billion in damage.[81]

Hurricane Grace[]

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 13 – August 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 125 mph (205 km/h) (1-min) 962 mbar (hPa) |

The NHC began to monitor a tropical wave south of the Cabo Verde Islands at 18:00 UTC on August 10.[83] The wave began to coalesce and by 15:00 UTC on August 13, the NHC considered the wave to be organized enough to be designated as Potential Tropical Cyclone Seven and began to issue advisories.[84] On August 14 at 09:00 UTC, the NHC upgraded the tropical depression to a tropical storm, assigning it the name Grace.[85] However, Grace weakened to a tropical depression on August 15 at around 18:00 UTC.[86] It made landfall on Hispaniola on August 16, just two days after the devastating Haiti earthquake. By 06:00 UTC the following day, it had reorganized back to a tropical storm. Grace's intensity continued to increase, and on August 18 at 15:00 UTC, the NHC upgraded the tropical storm to a Category 1 hurricane after reconnaissance aircraft found hurricane-force winds inside the system.[87] Little further intensification occurred before the system made landfall near Tulum, Quintana Roo, at 09:45 UTC on August 19.[88] Later, Grace weakened into a tropical storm again while crossing the Yucatan Peninsula.[89] However, after moving offshore of the peninsula and into the southwestern Gulf of Mexico at around 00:00 UTC on August 20, the storm began to re-strengthen, becoming a Category 1 hurricane at 12:00 UTC that same day. On August 21 at 03:00 UTC, Grace rapidly intensified to a Category 3 hurricane just fifteen hours later, becoming the first major hurricane of the season. After peaking with winds of 125 mph (205 km/h), the system made landfall near Tecolutla, Veracruz, at 06:00 UTC.[90][91][92][93] It then rapidly weakened over the mountains of central Mexico and dissipated there.[94] However, the remnants of Grace traveled across Mexico, and contributed to the development of Tropical Storm Marty in the Eastern Pacific.[95]

Grace was responsible for 14 deaths and $513 million in damages.[96][97][98][99]

Hurricane Henri[]

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 16 – August 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min) 986 mbar (hPa) |

At 00:00 UTC on August 15, the NHC began to monitor a small, yet well defined low-pressure system 200 miles north-northeast of Bermuda. At 03:00 UTC on August 16, the system intensified into a tropical depression when geostationary satellite data showed the convection being organized enough to be considered tropical cyclone. Eighteen hours later at 21:00 UTC, the system was upgraded to a tropical storm and received the name Henri.[100] Due to persistent wind shear, the center was consistently near the western edge of its convection.[101] On August 18, Henri intensified into a high-end tropical storm as the convection organized and wrapped around the mid-level circulation center.[102] However, the low-level center remained near the edge of the convection due to wind shear. For the next three days, Henri remained as a strong tropical storm whilst curving northwards as it rounded the western edge of the Azores High. At 15:00 UTC on August 21, Henri strengthened to a hurricane as shear relaxed, allowing the low-level and the mid-level circulation centers to align.[103] Henri made landfall on August 22, near Westerly, Rhode Island, around 16:15 UTC as a tropical storm, with maximum sustained winds of 60 mph (95 km/h).[104] Shortly after landfall, Henri rapidly weakened to a tropical depression as it made a small loop.[105] Late on the next day, Henri degenerated to an extratropical cyclone as it accelerated east-northeastwards.[106]

Hurricane Ida[]

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 26 – September 1 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-min) 929 mbar (hPa) |

On August 23, the NHC began to monitor a tropical wave over the eastern Caribbean Sea. As it approached Central America, favorable environmental conditions allowed it to rapidly organize, and by 15:00 UTC on August 26, it became the ninth tropical depression of the season.[107] An Air Force aircraft found tropical storm-force winds within the system six hours later, and it was subsequently given the name Ida. As Ida travelled northwest, high sea surface temperatures and ocean heat content coupled with low wind shear allowed it to rapidly intensify into a Category 1 hurricane. Ida made landfall as a Category 1 hurricane on the Isla de la Juventud in Cuba at 18:00 UTC on August 27 with winds of 75 mph (120 km/h) and a pressure of 987 mb. Later on the same day at 23:20 UTC, Ida made its second landfall at Pinar del Río, Cuba, with winds of 80 mph (130 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 985 mb.[108][109] After crossing Cuba and entering the Gulf of Mexico, Ida entered a region of increasingly favorable conditions, which allowed the storm's structure to improve, and satellite imagery showed that the system was beginning to develop a more robust outflow channel, and a nascent, cloud-filled eye accompanied that. Subsequently, it gradually intensified into a Category 2 hurricane by 18:00 UTC on August 28 and later to a Category 3 hurricane on August 29 at 06:00 UTC as the system cleared out a warm eye.[110] Ida then began a period of explosive intensification and was upgraded to a Category 4 hurricane just an hour after it became a major hurricane.[111] As Ida neared the Louisiana coast, it reached its peak intensity, with 1-minute sustained wind speeds of 150 mph (240 km/h) and a minimum central barometric pressure of 929 mbar (27.4 inHg), around 14:00 UTC.[112] Strengthening was then halted as the storm began an eyewall replacement cycle, forming a second eyewall, but Ida remained near its peak intensity. At 16:55 UTC on August 29, Ida made landfall near Port Fourchon, Louisiana, with sustained winds of 150 mph (240 km/h) and a central pressure of 930 mbar (27.46 inHg), tying the 1856 Last Island hurricane and Hurricane Laura as the strongest landfalling hurricane on record in Louisiana, as measured by maximum sustained wind, and trailing only Hurricane Katrina, as measured by central pressure at landfall.[113][114][115] A 172 mph (277 km/h) wind gust was reported in Port Fourchon[116] as Ida made landfall. Afterward, Ida weakened slowly at first, remaining a dangerous major hurricane.[117] As the storm moved further inland, Ida began to rapidly weaken. It dropped below hurricane strength early on August 30 before weakening to a depression later that day.[118][119] The system degenerated to a post-tropical cyclone two days later, as it moved over the central Appalachian Mountains.[120] The extratropical low continued northeastward into Atlantic Canada and stalled over the Gulf of St. Lawrence before being absorbed by another low developing to its east on September 4.[121]

Rains from Ida's precursor tropical wave triggered damaging floods and landslides across Venezuela, resulting in at least 20 deaths.[122] Trees were blown down and many homes were destroyed as Ida passed over Cuba. The storm caused widespread significant damage throughout coastal southwest Louisiana; parts of the New Orleans metropolitan area were left without power for several weeks. Ida also triggered a tornado outbreak that began with numerous weak tornadoes in Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama.[123] Ida's remnants subsequently spawned several destructive tornadoes and widespread flash flooding in the Northeastern United States with several flash flood emergencies and a tornado emergency (the first one ever to be issued for the region as well as the first to come from a tropical cyclone) being issued in areas stretching from Philadelphia to New York City. An EF2 tornado caused considerable damage in Annapolis, Maryland while a low-end EF2 tornado caused significant damage in Oxford, Pennsylvania. Another EF2 tornado caused a fatality in Upper Dublin Township, Pennsylvania before a destructive EF3 tornado heavily damaged or destroyed multiple homes in Mullica Hill, New Jersey. Widespread catastrophic flooding shut down most of the transportation system in New York City.[123][124] Ida caused an estimated $75.25 billion in damages and resulted in at least 115 deaths; this includes $75 billion in damage and 95 deaths in the United States.[80][125] The majority of those deaths occurred in Louisiana, New Jersey and New York.

Tropical Storm Kate[]

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 28 – September 1 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) 1004 mbar (hPa) |

On August 22, a tropical wave exited the west coast of Africa and entered the Atlantic. The wave, accompanied by a broad area of low pressure, moved quickly to the west and west-northward, passing well south of the Cabo Verde Islands. After decelerating and curving northwestward due to a weakness in the subtropical ridge, the system organized into a tropical depression at 06:00 UTC on August 28 while situated approximately 805 mi (1,295 km) east of the Leeward Islands. The depression moved generally northward and remained weak due to strong wind shear generated by a broad mid-to-upper-level trough. A temporary burst in convection allowed the depression to intensify into Tropical Storm Kate early on August 30 and soon peak with 45 mph (75 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 1,004 mbar (29.6 inHg). However, strong wind shear and very dry mid-level air caused Kate to weaken to a tropical depression on August 31. By 18:00 UTC on September 1, Kate degenerated into a trough about 960 mi (1,545 km) northeast of the Leeward Islands. The remnants continued north-northwestward until dissipating a few days later.[126]

Tropical Storm Julian[]

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 28 – August 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) 993 mbar (hPa) |

On August 20 at 00:00 UTC, the NHC began monitoring a tropical wave off of the coast of Africa.[127] The wave moved northwest toward the subtropical ridge of the Atlantic, then subsequently moved north. The disturbance then moved east, acquired low-level circulation and subsequently formed a tropical depression at 18:00 UTC on August 28.[128] The next day, the depression attained wind speeds of a tropical storm, and was named Julian.[129] The storm strengthened some and accelerated to the northeast. Late on August 29, it began to interact with a deep-layer area of low pressure located just east of Newfoundland.[130] Julian underwent extratropical transition and became post-tropical by 12:00 UTC on August 30.[128]

Hurricane Larry[]

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 31 – September 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 125 mph (205 km/h) (1-min) 953 mbar (hPa) |

On August 30, a strong tropical wave and an accompanying broad area of low pressure emerged off the west coast of Africa. Deep convection quickly began to increase around the eastern portion of the circulation as it moved over the far eastern tropical Atlantic. The system organized into a tropical depression at 18:00 UTC on August 31 while located about 320 mi (520 km) south-southeast of the Cabo Verde Islands. The depression intensified into Tropical Storm Larry six hours later. Located within favorable atmospheric and oceanic conditions, the cyclone steadily strengthened while moving generally westward across the Atlantic to the south of a strong mid-level ridge. A small inner-core developed late on September 1, and, by 06:00 UTC on September 2, a well-defined low- to midlevel eye feature became apparent, indicating that Larry had attained hurricane status. The storm intensified to Category 2 strength late on September 3. Then, after battling against some shear and an intrusion of dry mid-level air during an eyewall replacement cycle, Larry became a Category 3 major hurricane by 00:00 UTC September 4.[131] While maintaining Category 3 status for multiple days, Larry gained annular characteristics and completed two eyewall replacement cycles.[132][133][134][135]

Around 12:00 UTC on September 5, the hurricane peaked with maximum sustained winds of 125 mph (205 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 953 mbar (28.1 inHg).[131] However, by September 7, the eyewall became less defined as the convection decreased.[136] Early the next day, Larry weakened to a Category 2 hurricane as it began encountering decreasing sea surface temperatures. On September 9, the system weakened to a Category 1 hurricane while located roughly 285 mi (459 km) southeast of Bermuda. At 03:30 UTC on September 11, Larry made landfall in Newfoundland along Burin Peninsula. While crossing the Labrador Sea later that day, the storm transitioned into a post-tropical cyclone, which was subsequently absorbed by a larger extratropical system by early on September 12.[131]

Rough surf and rip currents generated by Larry's large wind field led to five drownings, one each in: the U.S. Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, South Carolina, Florida, and Virginia. In Newfoundland, high winds toppled many trees and power lines and damaged some roofs. Almost 61,000 customers lost electricity, with most along the Avalon Peninsula.[131] Damages assessed on Newfoundland were estimated at $80 million.[125] The remnants of the cyclone produced snowfall totals up to 4 ft (1.2 m) and hurricane-force winds in Greenland.[131]

Tropical Storm Mindy[]

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 8 – September 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) 1002 mbar (hPa) |

On August 30, the NHC began monitoring the southern Caribbean Sea where a broad area of low pressure was expected to form.[137] After the low formed, it moved along the Caribbean coast of Central America, across the Yucatán Peninsula, and into the Gulf of Mexico. After moving into the northeastern Gulf, the disturbance became better organized, and at 21:00 UTC on September 8, the NHC initiated advisories on Tropical Storm Mindy.[138] At 01:15 UTC on September 9, Mindy made landfall on St. Vincent Island, Florida, about 10 mi (15 km) west-southwest of Apalachicola, Florida, with maximum sustained winds of 45 mph (75 km/h).[139] A few hours later, it weakened to a tropical depression as it tracked inland,[140] and by 15:00 UTC, had moved offshore the coast of Georgia into the Atlantic Ocean.[141] Mindy became post-tropical and merged with a cold front early on September 10.[142]

Hurricane Nicholas[]

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 12 – September 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min) 988 mbar (hPa) |

On September 9, the NHC began monitoring the northern portion of a tropical wave over the western Caribbean Sea for potential development as it moved across northern Central America and the Yucatán Peninsula toward the Bay of Campeche.[143] By the next day, the wave was interacting with a surface trough over the southwestern Gulf of Mexico, producing widespread but disorganized showers and thunderstorms across the region.[144] Showers and thunderstorms associated with this system increased and become better organized on September 12, and as a result, advisories were initiated at 15:00 UTC on Tropical Storm Nicholas.[145] On September 14 at 03:00 UTC, a WeatherFlow Station at Matagorda Bay reported sustained winds of 76 mph (122 km/h), prompting the NHC to upgrade the storm to hurricane status.[146] Shortly thereafter, at 05:30 UTC, Nicholas made landfall about 10 mi (15 km) west-southwest of Sargent Beach, Texas, with maximum sustained winds of 75 mph (120 km/h).[147] The system quickly weakened inland to tropical storm strength, as it moved to near Galveston Bay.[148] By 00:00 UTC on September 15, it had weakened to a tropical depression as the system moved toward the east-northeast.[149] Early the following day, while stationary near Marsh Island, along the Louisiana coast, Nicholas became post-tropical.[150]

According to RMS, insured losses from Hurricane Nicholas ranged from $1.1 to $2.2 billion (2021 USD).[151]

Tropical Storm Odette[]

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 17 – September 18 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) 1005 mbar (hPa) |

On September 11, the NHC began monitoring an area of disturbed weather over the southeastern Bahamas.[152] As the system moved northwestward to north-northwestward, a low-pressure area formed well east of northeast Florida early on September 16. Despite the low having a relatively well-defined circulation, convection was disorganized and displaced from the center due to wind shear. By 18:00 UTC on September 17, the system organized into Tropical Storm Odette about 175 mi (280 km) east of the North Carolina–Virginia state line. Early on the following day, however, the cyclone was already beginning to lose tropical characteristics due to colder and drier air.[153] During this process, its deep convection was consistently displaced well to the east of a poorly-defined center due to strong westerly wind shear. The system's circulation was elongated from southwest to northeast and contained multiple low-cloud swirls.[154] Odette completed extratropical transition by 12:00 UTC on September 18, about 290 mi (465 km) east-southeast of Atlantic City, New Jersey. The remnants of Odette retained gale-force winds and continued moving out into the central Atlantic, curving northeastward, before turning southward, making a slow counterclockwise curve before turning back south-southwestward. The extratropical low degenerated into a trough on September 27.[153] During this time, the NHC monitored Odette's remnants for the potential to redevelop into a subtropical or tropical cyclone.[155]

Tropical Storm Peter[]

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 19 – September 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 1005 mbar (hPa) |

At 06:00 UTC on September 11, the NHC began monitoring a tropical wave expected to move off the west coast of Africa.[156] The wave emerged into the Atlantic between September 13 and September 14, producing a large burst of convection but lacking a closed circulation. Moving westward, convection became more concentrated over the next few days, and by late on September 18, the system acquired a closed circulation according to a NOAA buoy and satellite imagery. As a result, a tropical depression developed by 00:00 UTC on September 19 about 605 mi (975 km) east of the Leeward Islands. Six hours later, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Peter. Relatively light wind shear and warm seas allowed Peter to peak with winds of 50 mph (85 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 1,005 mbar (29.7 inHg) late on September 19. However, as the storm approached the northern Leeward Islands on September 20, it encountered nearly 35 mph (55 km/h) of southwesterly wind shear from a nearby upper low. As a result, Peter's low-level center was displaced west of its showers and thunderstorms. Later on September 21, the system weakened to a tropical depression and degenerated into a trough about 230 mi (370 km) north of Puerto Rico around 00:00 UTC on September 23.[157] Although the NHC monitored the remnants due to the potential for redevelopment,[158] the system dissipated well south of Newfoundland on September 29.[157]

The system brought heavy rain showers to the northern Leeward Islands, Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico on September 21, as it tracked to their north. In Puerto Rico, the towns of Lares and Morovis both observed up to 3.76 in (96 mm) of precipitation, although parts of the former may have experienced rainfall totals up to 5 to 6 in (130 to 150 mm).[157]

Tropical Storm Rose[]

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 19 – September 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 1003 mbar (hPa) |

At 00:00 UTC on September 15, the National Hurricane Center began monitoring a tropical wave approaching the Atlantic coast of Africa.[159] After moving into the far eastern tropical Atlantic, it formed a low pressure center, though it remained disorganized. By 03:00 UTC on September 19, the disturbance had acquired a well-defined circulation and enough organized deep convection for it to be designated a tropical depression.[160] Later that day, satellite images showed that the deep convection had increased within the cyclone and that its overall structure had continued to improve. As a result, the cyclone was upgraded to a tropical storm and given the name Rose.[161] As the storm moved northwestward over the eastern tropical Atlantic between September 20 and 21, it was beset by high wind shear, leaving its low-level circulation center exposed and all of the heavy thunderstorm activity confined to the east side of the center.[162] Early on September 22, Rose weakened to a tropical depression,[163] and then transitioned into a post-tropical cyclone the following day.[164]

Hurricane Sam[]

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 22 – October 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 155 mph (250 km/h) (1-min) 929 mbar (hPa) |

On September 19, the NHC began monitoring a tropical wave over West Africa for potential tropical cyclogenesis.[165] After emerging into the Atlantic, the showers and thunderstorms within the wave increased on September 21, and began exhibiting signs of organization.[166] The disturbance organized further through the following day, and by 21:00 UTC on September 22, its low-level circulation had become well-defined enough to mark the formation of Tropical Depression Eighteen.[167] The system quickly strengthened as it moved westward across the open ocean, and at 15:00 UTC on September 23, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Sam.[168] Sam continued to rapidly intensify, with its winds reaching 70 mph (110 km/h) 24 hours after its initial designation.[169] At 09:00 UTC on September 24, Sam was upgraded to a Category 1 hurricane as it continued intensifying.[170] After briefly leveling out in intensity, the storm resumed rapid intensification, reaching Category 3 hurricane status at 15:00 UTC on September 25.[39][171] Satellite images showed a well-defined eye embedded in a developing central dense overcast, and following an increase in Dvorak intensity estimates, Sam was upgraded into a Category 4 hurricane six hours later.[172]

On September 26, the NHC estimated that Sam reached its peak intensity between 19:00 and 22:00 UTC, with the storm likely attaining maximum sustained winds of 155 mph (250 km/h) and a central minimum pressure of 929 mbar (27.4 inHg), making Sam a high-end Category 4 hurricane.[173] Sam briefly weakened into a Category 3 hurricane due to an eyewall replacement cycle before re-strengthening back to a Category 4 hurricane at 03:00 UTC on September 28.[174][175][176] The intensity then fluctuated between 130–140 mph (215–220 km/h) as it went through another eyewall replacement cycle, before Sam began another strengthening trend while growing in size.[177] Early on October 1, Sam reached its secondary peak, with maximum sustained winds of 150 mph (240 km/h) and a central pressure of 934 mbar (27.6 inHg), while accelerating north-northwestward.[178][179] The storm turned northward and then northeastward, passing east-southeast of Bermuda.[180] Around this time, Sam gradually began to weaken as it tracked over cooler sea surface temperatures.[181] Sam was downgraded from a major hurricane on October 3, but managed to briefly re-strengthen slightly following another eyewall replacement cycle later that day.[182][183] The hurricane's cloud pattern began to degrade again on October 4, and it weakened to Category 1 strength late that day.[184] Early on October 5, the hurricane completed a dynamic extratropical transition and transitioned to a powerful post-tropical cyclone over the far North Atlantic between Newfoundland and Iceland while being absorbed by a large mid-latitude extratropical cyclone.[185]

Sam brought dangerous swells, mainly on the East Coast of the U.S., although Sam was 900 miles from the coast of the U.S.[186] Although Sam passed well east of Bermuda, however, it brought tropical-storm force winds to the island.[187] Additionally, as Sam tracked to the north, snow was expected in Iceland as a result.[188]

Subtropical Storm Teresa[]

| Subtropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 24 – September 25 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) 1008 mbar (hPa) |

A weak cold front first began pushing into the western Atlantic on September 19. As this front interacted with an upper-level low moving in from the west, it generated an area of disturbed weather, with increasing convection located near a developing surface center. That disturbance, nestled underneath the upper-level low, developed into a subtropical depression around 06:00 UTC on September 24 while located about 175 mi (280 km) east-southeast of Bermuda. Over the next 12 hours, the depression intensified into Subtropical Storm Teresa and reached peak winds of 45 mph (75 km/h). As the cyclone moved northwest but then veered northeast, it encountered dry air and wind shear, which promptly caused its weakening, and Teresa degenerated to a remnant low around 18:00 UTC on September 25. The low weakened to a trough the next day, and that trough was absorbed by a frontal system on September 27.[189]

Tropical Storm Victor[]

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 29 – October 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) 997 mbar (hPa) |

A vigorous tropical wave moved off Africa on September 27 and swiftly organized into a tropical depression around 12:00 UTC on September 29. At that time, the system was located about 535 mi (860 km) south of Cabo Verde. The newly formed cyclone moved west-northwest on the south side of a ridge. While ocean temperatures and wind shear values were conducive, the storm was surrounded by some dry air that intermittently became entrained into its circulation. The depression intensified into Tropical Storm Victor at 18:00 UTC on September 29 and reached peak winds of 65 mph (100 km/h) about two days later. As Victor turned northwest, it encountered starkly higher wind shear which resulted in its weakening. Its convection became displaced and its low-level circulation elongated, which led to its degeneration to a trough around 12:00 UTC on October 4. The remnants turned west and dissipated over the open Atlantic the next day.[190]

Tropical Storm Wanda[]

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 31 – November 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 987 mbar (hPa) |

On October 24, the NHC began monitoring a non-tropical disturbance just off East Coast of the U.S., anticipating that it would shortly develop into a strong low-pressure system, a nor'easter, as it moved northward up the coast, and then possibly develop tropical or subtropical characteristics afterward while moving away from the coast.[191][192] The storm brought heavy rainfall, damaging winds, and coastal flooding to areas in the Northeast U.S. between October 25 and 27. It acquired subtropical characteristics early on October 31, while located over the central Atlantic, and was given the name Wanda.[193] By 21:00 UTC on November 1, the system had transitioned to a tropical storm.[194] After meandering several hundred nautical miles west of the Azores for nearly a week, Wanda weakened and began accelerating northeastward late on November 6, as it interacted with a deepening mid-latitude low pressure system over the northern Atlantic.[195] The next day, its low level circulation ceased generating deep convection and the north side began opening-up into a trough due to interaction with the other system. As a result, Wanda was deemed by the NHC to have become a post-tropical low as of its 15:00 UTC advisory.[196]

The precursor to Wanda caused over $200 million in damages across the Northeastern U.S.;[193] two storm-related deaths were reported.[197] There were no reports of damage or deaths associated with Wanda itself.

Storm names[]

The following list of names was used for named storms that formed in the North Atlantic in 2021.[198] Retired names, if any, will be announced by the World Meteorological Organization in the spring of 2022. The names not retired from this list will be used again in the 2027 season. This is the same list used in the 2015 season, with the exceptions of Elsa and Julian, which replaced Erika and Joaquin, respectively. The names Elsa, Julian, Rose, Sam, Teresa, Victor, and Wanda were used for the first time this year.

Season effects[]

This is a table of all of the storms that formed in the 2021 Atlantic hurricane season. It includes their duration, names, damages, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a wave, or a low, and all of the damage figures are in 2021 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category

at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Ref(s)

| ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ana | May 22 – 23 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1004 | Bermuda | None | None | |||

| Bill | June 14 – 15 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 992 | East Coast of the United States, Atlantic Canada | None | None | |||

| Claudette | June 19 – 22 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1003 | Southern Mexico, Southern United States, Atlantic Canada | $375 million | 4 (10) | [45] | ||

| Danny | June 27 – 29 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1009 | South Carolina, Georgia | $5,000 | None | [50] | ||

| Elsa | July 1 – 9 | Category 1 hurricane | 85 (140) | 991 | Lesser Antilles, Venezuela, Greater Antilles, South Atlantic United States, Northeastern United States, Atlantic Canada, Greenland, Iceland | $1.2 billion | 5 | [79][80] | ||

| Fred | August 11 – 17 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 991 | Lesser Antilles, Greater Antilles, The Bahamas, Southeastern United States, Eastern Great Lakes Region, Northeastern United States, Southern Quebec, The Maritimes | $1.3 billion | 5 (2) | [81] | ||

| Grace | August 13 – 21 | Category 3 hurricane | 125 (205) | 962 | Lesser Antilles, Greater Antilles, Yucatan Peninsula, Central Mexico | $513 million | 14 (1) | [96][97][98][99] | ||

| Henri | August 16 – 23 | Category 1 hurricane | 75 (120) | 986 | Bermuda, Northeastern United States, Southern Nova Scotia | $650 million | 2 | [96][199][200][201] | ||

| Ida | August 26 – September 1 | Category 4 hurricane | 150 (240) | 929 | Venezuela, Colombia, Cayman Islands, Cuba, Southern United States, Northeastern United States, Atlantic Canada | ≥ $75.25 billion | 72 (43) | [80][122][125] | ||

| Kate | August 28 – September 1 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1004 | None | None | None | |||

| Julian | August 28 – 30 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 993 | None | None | None | |||

| Larry | August 31 – September 11 | Category 3 hurricane | 125 (205) | 953 | Lesser Antilles, Bermuda, East Coast of the United States, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, Greenland | $80 million | 5 | [125][131] | ||

| Mindy | September 8 – 10 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1002 | Colombia, Central America, Yucatán Peninsula, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina | Minimal | None | |||

| Nicholas | September 12 – 16 | Category 1 hurricane | 75 (120) | 988 | Mexico, Gulf Coast of the United States | >$1 billion | None | [80][151] | ||

| Odette | September 17 – 18 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1005 | East Coast of the United States, Atlantic Canada | None | None | |||

| Peter | September 19 – 22 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1005 | Hispaniola, Leeward Islands, Puerto Rico | None | None | |||

| Rose | September 19 – 23 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1003 | None | None | None | |||

| Sam | September 22 – October 5 | Category 4 hurricane | 155 (250) | 929 | West Africa, Leeward Islands, Puerto Rico, Bermuda, Iceland | Unknown | None | |||

| Teresa | September 24 – 25 | Subtropical storm | 45 (75) | 1008 | Bermuda | None | None | |||

| Victor | September 29 – October 4 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 997 | None | None | None | |||

| Wanda | October 31 – November 7 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 987 | Southern United States, Mid-Atlantic states, Northeastern United States, Bermuda, Atlantic Canada | >$200 million | 0 (2) | [193][197] | ||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 21 systems | May 22 – November 7 | 155 (250) | 929 | >$80.568 billion | 106 (58) | |||||

See also[]

- Weather of 2021

- Tropical cyclones in 2021

- 2021 Pacific hurricane season

- 2021 Pacific typhoon season

- 2021 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 2020–21, 2021–22

- Australian region cyclone seasons: 2020–21, 2021–22

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 2020–21, 2021–22

Notes[]

- ^ While not explicitly given as the intensity in advisories, an NHC forecast discussion and best track data indicate that Hurricane Sam peaked with winds at 135 knots (155 mph; 250 km/h) and a pressure of 929 mbar (27.43 inHg). Hurricane Ida also had a pressure of 929 mbar however only had winds of 130 knots (150 mph; 240 km/h).

- ^ An average Atlantic hurricane season, as defined by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, has fourteen tropical storms, seven hurricanes and three major hurricanes.[3]

- ^ Hurricanes reaching Category 3 (111 miles per hour or 179 kilometers per hour) and higher on the five-level Saffir–Simpson wind speed scale are considered major hurricanes.[3]

- ^ September 10 is the climatological mid-point of the Atlantic hurricane season.[34]

References[]

- ^ a b Rice, Doyle (November 30, 2021). "Lots of storms but a slow finish: Busy 2021 Atlantic hurricane season ends today". USA Today. Retrieved November 30, 2021.

- ^ King, Simon (December 1, 2021). "2021 hurricane season was third most active". BBC News. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "Background Information: North Atlantic Hurricane Season". College Park, Maryland: Climate Prediction Center. May 22, 2019. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ "Hurricane Season Information". Frequently Asked Questions About Hurricanes. Miami, Florida: NOAA Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. June 1, 2018. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ Cetoute, Devoun; Harris, Alex (May 22, 2021). "Subtropical Storm Ana forms. It's the seventh year in a row with an early named storm". Miami Herald. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ^ Klotzbach, Phil (June 28, 2021). "5th Atlantic season on record to have 3 June named storm formations". Twitter. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- ^ Masters, Jeff (July 1, 2021). "Tropical Storm Elsa is earliest fifth named storm on record in the Atlantic". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

- ^ Erdman, Jonathan (November 30, 2021). "2021 Hurricane Season Recap: Louisiana, Northeast Destruction Gives Way to Unusually Quiet End". The Weather Channel. Retrieved November 30, 2021.

- ^ Allen, Greg (February 26, 2021). "Hurricane Forecasts Will Start Earlier In 2021". NPR. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- ^ Fox, Alex (October 8, 2021). "'Saildrone' Captures First-Ever Video From Inside a Category 4 Hurricane". Smithsonian. Washington, D.C. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ a b "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. May 25, 2020.

- ^ a b c Saunders, Marc; Lea, Adam (December 9, 2020). "Extended Range Forecast for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2021" (PDF). TropicalStormRisk.com. London, UK: Dept. of Space and Climate Physics, University College London. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ a b "CSU researchers predicting above-average 2021 Atlantic hurricane season". Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. April 8, 2021. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ Mann, Michael E.; Brouillette, Daniel J.; Kozar, Michael (April 12, 2021). "The 2021 North Atlantic Hurricane Season: Penn State ESSC Forecast". University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Earth System Science Center. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ a b Saunders, Marc; Lea, Adam (April 13, 2021). "April Forecast Update for North Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2021" (PDF). TropicalStormRisk.com. London, UK: Dept. of Space and Climate Physics, University College London. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ a b Davis, Kyle; Zeng, Xubin (April 13, 2021). "Forecast of the 2021 Hurricane Activities over the North Atlantic" (PDF). Tucson, Arizona: Department of Hydrology and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Arizona. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ a b Peake, Tracy (April 14, 2021). "2021 Hurricane Season Will Be Active, NC State Researchers Predict". Raleigh, North Carolina: North Carolina State University. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ Belles, Jonathan; Erdman, Jonathan (April 15, 2021). "2021 Atlantic Hurricane Season Expected to Be More Active Than Normal, The Weather Company Outlook Says". Hurricane Central. Atlanta, Georgia: The Weather Channel. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ a b Belles, Jonathan; Erdman, Jonathan (May 13, 2021). "2021 Atlantic Hurricane Season Storm Numbers Increase in Our Latest Outlook". Hurricane Central. Atlanta, Georgia: The Weather Channel. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- ^ a b "NOAA predicts another active Atlantic hurricane season". National Hurricane Center. May 20, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ a b "UKMO North Atlantic tropical storm seasonal forecast 2021". UK Met Office. May 20, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ Saunders, Marc; Lea, Adam (May 27, 2021). "Pre-Season Forecast for North Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2021" (PDF). TropicalStormRisk.com. London, UK: Dept. of Space and Climate Physics, University College London. Retrieved May 27, 2021.

- ^ Klotzbach, Philip; Bell, Michael; Jones, Jhordanne (June 3, 2021). "Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and Landfall Strike Probability for 2021" (PDF). Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ a b Davis, Kyle; Zeng, Xubin (June 16, 2021). "Forecast of the 2021 Hurricane Activities over the North Atlantic" (PDF). Tucson, Arizona: Department of Hydrology and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Arizona. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

- ^ a b Saunders, Marc; Lea, Adam (July 6, 2021). "July Forecast for North Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2021" (PDF). TropicalStormRisk.com. London, UK: Dept. of Space and Climate Physics, University College London. Retrieved July 6, 2021.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and Landfall Strike Probability for 2021" (PDF).

- ^ "North Atlantic tropical storm seasonal forecast 2021".

- ^ "Atlantic hurricane season shows no signs of slowing | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration".

- ^ Klotzbach, Philip; Bell, Michael; Jones, Jhordanne (August 5, 2021). "Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and Landfall Strike Probability for 2021" (PDF). Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ a b Saunders, Marc; Lea, Adam (August 5, 2021). "August Forecast Update for North Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2021" (PDF). TropicalStormRisk.com. London, UK: Dept. of Space and Climate Physics, University College London. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ Samenow, Jason (May 22, 2021). "For seventh straight year, a named storm forms in Atlantic ahead of hurricane season". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ^ "Tropical Storm Henri Forms in the Atlantic". The New York Times. August 16, 2021. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ Masters, Jeff; Henson, Bob (September 10, 2021). "Cat 1 Larry aims at Newfoundland; Cat 5 Chanthu threatens Taiwan; Cat 2 Olaf hits Baja". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved September 11, 2021.

- ^ a b Masters, Jeff (September 9, 2021). "Mindy hits Florida Panhandle; Cat 1 Larry grazes Bermuda; Cat 4 Chanthu takes aim at Taiwan, and Cat 1 Olaf threatens Baja". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Center for Environmental Communication. Retrieved September 9, 2021.

- ^ Henson, Bob; Masters, Jeff (September 12, 2021). "Tropical Storm Nicholas to douse Texas coast with torrential rains". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved September 12, 2021.

- ^ Jones, Zoe Christen; Martinez (September 14, 2021). "Hurricane Nicholas makes landfall and could bring "life-threatening" flash flooding to parts of Texas and Louisiana". CBS News. Retrieved September 14, 2021.

- ^ Henson, Bob; Masters, Jeff (September 20, 2021). "Tropical storms Peter and Rose likely to be joined by Sam this week". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ^ Papin, Philippe (September 24, 2021). Hurricane Sam Discussion Number 8 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- ^ a b Masters, Jeff (September 25, 2021). "Sam rapidly intensifies into a major category 3 hurricane". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale climate Connections. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- ^ Masters, Jeff; Hensen, Bob (September 29, 2021). "Hurricane Sam still a Cat 4; Tropical Depression 20 forms off coast of Africa". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ Kegges, Jonathan; Cokinos, Samara (October 30, 2021). "Tropics: Subtropical Storm Wanda forms over northern Atlantic". clickorlando.com. Orlando, Florida: WKMG-TV. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ "Northern Hemisphere Tropical Cyclone Activity for 2021 (2021/2022 for the Southern Hemisphere)". Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University.

- ^ Reinhart, Brad (June 30, 2021). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Ana (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- ^ Brown, Daniel (September 27, 2021). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Bill (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 27, 2021.

- ^ a b Papin, Philippe; Berg, Robbie (January 6, 2022). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Claudette (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 7, 2022.

- ^ Fernando, Christine. "High winds, tornadoes and drenching rain reported as Tropical Depression Claudette batters parts of Gulf Coast". USA TODAY (in American English). Retrieved June 20, 2021.

- ^ Taylor, Derrick Bryson (June 19, 2021). "Tropical Storm Claudette Spawns Tornadoes and Brings Heavy Rains to the South". The New York Times. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

- ^ "Survey crews are currently out investigating the Brewton, AL tornado. So far damage has suggested the tornado was EF-2 intensity in eastern Brewton. These results are preliminary and the survey is still ongoing". Twitter. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

- ^ "Tropical Depression Claudette claims 14 lives in Alabama". Twitter. Retrieved June 22, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Latto, Andy (October 14, 2021). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Danny (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ Rivera-Acevedo, Evelyn (June 24, 2021). Tropical Weather Discussion: Atlantic [1205 UTC Thu Jun 24 2021] (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 28, 2021.

- ^ Klotzbach, Philip [@philklotzbach] (June 28, 2021). "Tropical Storm #Danny has made landfall in South Carolina - the first June named storm to make landfall in South Carolina since #Hurricane One of 1867" (Tweet). Archived from the original on June 30, 2021. Retrieved June 29, 2021 – via Twitter.

- ^ Latto, Andrew (June 29, 2021). Remnants Of Danny Discussion Number 4 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- ^ King, Jayme (June 28, 2021). "NHC: Danny weakens to depression after making landfall in South Carolina". FOX 35 Orlando (in American English). Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- ^ Curley, Molly (June 29, 2021). "Tropical Storm Danny brings lightning, flooding locally". WSAV-TV (in American English). Archived from the original on June 30, 2021. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- ^ "Tropical depression brings heavy rainfall to Georgia overnight". FOX 5 Atlanta (in American English). June 28, 2021. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- ^ "Storm Events Database: "Tropical Storm Danny"". National Centers for Environmental Information. 2021. Retrieved November 23, 2021.

- ^ Jack Beven (June 29, 2021). "Five-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ Richard Pasch (June 29, 2021). "Five-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ Jack Beven (June 30, 2021). "Potential Tropical Cyclone Five Forecast Discussion Number 1". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ a b Richard Pasch (July 1, 2021). "Tropical Storm Elsa Discussion Number 3". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- ^ John Cangialosi; Robbie Berg (July 2, 2021). "Tropical Storm Elsa Discussion Number 7". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ Jack Beven; Andrew Latto; David Zelinsky (July 2, 2021). "Hurricane Elsa Update Statement". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ Jack Bevan (July 3, 2021). Tropical Storm Elsa Discussion Number 13. www.nhc.noaa.gov (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ^ Stacy R. Steward; Philippe Papin (July 4, 2021). Tropical Storm Elsa Discussion Number 15. www.nhc.noaa.gov (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ John Cangialosi; Brad Reinhart (July 4, 2021). "Tropical Storm Elsa Discussion Number 16". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ Richard Pasch (July 5, 2021). Tropical Storm Elsa Discussion Number 22. www.nhc.noaa.gov (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (July 6, 2021). Tropical Storm Elsa Discussion Number 23. www.nhc.noaa.gov (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart; Andrew Latto (July 7, 2021). Hurricane Elsa Intermediate Advisory Number 27A...Corrected. www.nhc.noaa.gov (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (July 7, 2021). Hurricane Elsa Discussion Number 28. www.nhc.noaa.gov (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ Jack Beven (July 7, 2021). Tropical Storm Elsa Intermediate Advisory Number 28A. www.nhc.noaa.gov (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ Jack Beven (July 7, 2021). Tropical Storm Elsa Discussion Number 29. www.nhc.noaa.gov (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ Richard Pasch (July 7, 2021). Tropical Storm Elsa Forecast Discussion Number 30. www.nhc.noaa.gov (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ Richard Pasch; Philippe Papin; Daniel Brown (July 7, 2021). Tropial Storm Elsa Advisory Number 30. www.nhc.noaa.gov (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ Eric S. Blake (July 8, 2021). Tropical Storm Elsa Discussion Number 32. www.nhc.noa.gov (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

- ^ Richard Pasch (July 8, 2021). Tropical Storm Elsa Discussion Number 35. www.nhc.noaa.gov (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

- ^ Daniel Brown; David Zelinsky (July 9, 2021). Post-Tropical Cyclone Elsa Intermediate Advisory Number 38A. www.nhc.noaa.gov (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

- ^ Phil Helsel; Wilson Wong (July 8, 2021). "Tropical Storm Elsa brings heavy rain to Carolinas after leaving 1 dead in Florida". NBC News. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

- ^ a b "Saint Lucia Crop Damage From Hurricane Elsa Put At Over $34 Million". St. Lucia Times News (in American English). July 4, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters: Events". Asheville, North Carolina: National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved January 10, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Berg, Robbie (November 19, 2021). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Fred (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 23, 2021.

- ^ "Tropical Storm Fred nearing the Dominican Republic". CNBC. Associated Press. August 11, 2021. Retrieved November 23, 2021.

- ^ Latto, Andrew (August 10, 2021). "Five-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ "Potential Tropical Cyclone Seven Advisory Number 1". www.nhc.noaa.gov (in American English). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ Andrew Latto (August 14, 2021). "Tropical Storm Grace Discussion Number 4". www.nhc.noaa.gov (in American English). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 14, 2021.

- ^ "Remnants of Grace".

- ^ Richard Pasch (August 18, 2021). "Hurricane Grace Discussion Number 21". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ Stewart, Stacy; Berg, Robbie (August 19, 2021). "Hurricane Grace Tropical Cyclone Update". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ David Zelinsky (August 19, 2021). "Tropical Storm Grace Discussion Number 25". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Jack Beven (August 19, 2021). "Tropical Storm Grace Intermediate Advisory Number 26A". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ "Hurricane Grace Public Advisory 28A". www.nhc.noaa.gov. August 20, 2021. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ "Hurricane Grace Public Advisory 31". www.nhc.noaa.gov. August 21, 2021. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ Latto, Andrew (August 21, 2021). "Hurricane GRACE Public Advisory Number 31A". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ "Grace Dissipates over Mainland Mexico; Flooding Rain Expected to Continue". The Weather Channel. August 21, 2021. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ Howes, Nathan (August 23, 2021). "Rejuvenated Tropical Storm Marty arises from Grace's remains". The Weather Network. Retrieved September 3, 2021 – via Yahoo! News.

- ^ a b c Global Catastrophe Recap August 2021 (PDF) (Report). Aon Benfield. September 9, 2021. Retrieved September 10, 2021.

- ^ a b "En total ya suman 12 muertos por paso de "Grace" en México". infobae.com. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- ^ a b "Afectó 'Grace' a 58 de 212 municipios veracruzanos". jornada.com.mx. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- ^ a b Matthew Lerner (August 26, 2021). "Grace's damage in Mexico, Caribbean pegged at about $330M". Business Insurance Journal. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- ^ Daniel Brown (August 16, 2021). "Tropical Storm Henri Advisory Number 4". www.nhc.noaa.gov (in American English). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ John Cangialosi (August 17, 2021). "Tropical Storm Henri Discussion Number 7". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 17, 2021.

- ^ Cangialosi, John (August 18, 2021). "Tropical Storm Henri Advisory Number 12". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ Cangialosi, John (August 21, 2021). "Hurricane Henri Advisory Number 23". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ "Henri makes landfall in Westerly, R.I., may stall over western Massachusetts". Boston, Massachusetts: WCVB-TV. August 22, 2021. Retrieved August 22, 2021.