Adam's Bridge

Coordinates: 9°07′16″N 79°31′18″E / 9.1210°N 79.5217°E

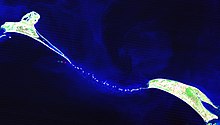

Adam's Bridge,[a] also known as Rama's Bridge or Rama Setu,[b] is a chain of natural limestone shoals, between Pamban Island, also known as Rameswaram Island, off the south-eastern coast of Tamil Nadu, India, and Mannar Island, off the north-western coast of Sri Lanka. Geological evidence suggests that this bridge is a former land connection between India and Sri Lanka.[2]

The feature is 48 km (30 mi) long and separates the Gulf of Mannar (southwest) from the Palk Strait (northeast). Some of the regions are dry, and the sea in the area rarely exceeds 1 metre (3 ft) in depth, thus hindering navigation.[2] It was reportedly passable on foot until the 15th century when storms deepened the channel. Rameshwaram temple records say that Adam's Bridge was entirely above sea level until it broke in a cyclone in 1480.[3][4]

Historical mentions and etymology

The ancient Indian Sanskrit epic Ramayana (7th century BCE to 3rd century CE) written by Valmiki mentions a bridge[5] constructed by god Rama through his Vanara (ape-men) army to reach Lanka and rescue his wife Sita from the Rakshasa king, Ravana.[5][6] The location of the Lanka of the Ramayana has been widely interpreted as being present-day Sri Lanka making this stretch of land Nala's or Rama's bridge. Analysis of several of the older Ramayana versions by scholars for evidence of historicity have led to the identification of Lankapura no further south than the Godavari River. These are based on geographical, botanical, and folkloristic evidences as no archaeological evidence has been found.[7][8] Scholars differ on the possible geography of the Ramayana but several suggestions since the work of H.D. Sankalia locate the Lanka of the epic somewhere in the eastern part of present day Madhya Pradesh.[9]

The western world first encountered it in Ibn Khordadbeh's Book of Roads and Kingdoms (c. 850), in which he refers to it as Set Bandhai or Bridge of the Sea.[10] Some early Islamic sources refer to a mountain in Sri Lanka as Adam's Peak (where Adam supposedly fell to earth). The sources describe Adam as crossing from Sri Lanka to India via the bridge after his expulsion from the Garden of Eden,[11] leading to the name of Adam's Bridge.[12] Alberuni (c. 1030) was probably the first to describe it in such a manner.[10] A British cartographer in 1804 prepared the earliest map that calls this area by the name Adam's bridge.[5]

Location

The bridge starts as a chain of shoals from the Dhanushkodi tip of India's Pamban Island. It ends at Sri Lanka's Mannar Island. Pamban Island is accessed from the Indian mainland by the 2-km-long Pamban Bridge. Mannar Island is connected to mainland Sri Lanka by a causeway.

Geological evolution

Considerable diversity of opinion and confusion exists about the nature and origin of this structure. In the 19th century, two significant theories were prominent in explaining the structure. One considered it to be formed by the process of accretion and rising of the land. At the same time the other surmised that it was established by the breaking away of Sri Lanka from the Indian mainland.[13] The friable calcareous ridges later broke into large rectangular blocks, which perhaps gave rise to the belief that the causeway is an artificial construction.[14]

According to V. Ram Mohan of the Centre of Natural Hazards and Disaster Studies of the University of Madras, "reconstruction of the geological evolution of the island chain is a challenging task and has to be carried out based on circumstantial evidence".[15] The lack of comprehensive field studies explains many of the uncertainties regarding the nature and origin of Adam's Bridge. It mostly consists of a series of parallel ledges of sandstone and conglomerates that are hard at the surface and grow coarse and soft as they descend to sandy banks.[16]

Studies have variously described the structure as a chain of shoals, coral reefs, a ridge formed in the region owing to thinning of the earth's crust, a double tombolo,[17] a sand spit, or barrier islands. One account mentions that this landform was formerly the world's largest tombolo. The tombolo split into a chain of shoals by a slight rise in mean sea level a few thousand years ago.[18] The tombolo model affirms a constant sediment source and a high uni-directional or bi-directional (monsoonal) longshore current.

The Marine and Water Resources Group of the Space Applications Centre (SAC) of the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) concludes that Adam's Bridge comprises 103 small patch reefs.[16] The SAC study, based on satellite remote sensing data but without actual field verification, finds the reefs lying in a linear pattern. The feature consists of the reef crest (flattened, emergent, especially during low tides, or nearly emergent segment of a reef), sand cays (accumulations of loose coral sands and beach rock) and intermittent deep channels. Other studies variously designate the coral reefs as ribbon and atoll reefs.[19]

The geological process that gave rise to this structure has been attributed in one study to crustal down warping, block faulting, and mantle plume activity.[20] In contrast, another theory attributes it to continuous sand deposition and the natural process of sedimentation leading to the formation of a chain of barrier islands related to rising sea levels.[19] Another theory affirms the origin and linearity of the bridge to the old shoreline (implying that the two landmasses of India and Sri Lanka were once connected) from which shoreline coral reefs developed.

Another study attributes the origin of the structure to longshore drifting currents which moved in an anticlockwise direction in the north and clockwise direction in the south of Rameswaram and Talaimannar. The sand could have been dumped in a linear pattern along the current shadow zone between Dhanushkodi and Talaimannar with the later accumulation of corals over these linear sand bodies.[21] In a diametrically opposing view, another group of geologists propose a crustal thinning theory, block faulting and a ridge formed in the region owing to thinning and asserts that development of this ridge augmented the coral growth in the area and in turn coral cover acted as a 'sand trapper'.[19]

One study tentatively concludes that there is insufficient evidence to indicate eustatic emergence and that the raised reef in southern India probably results from a local uplift.[22] Other studies also conclude that during periods of lowered sea level over the last 100,000 years, Adam's Bridge has provided an intermittent land connection between India and Sri Lanka. According to famous ornithologists Sidney Dillon Ripley and Bruce Beehler, this supports the vicariance model for speciation in some birds of the Indian Subcontinent.[23]

Age

The studies under "Project Rameswaram" of the Geological Survey of India (GSI), which included dating of corals, indicate Rameswaram Island evolved beginning 125,000 years ago. Radiocarbon dating of samples in this study suggests the domain between Rameswaram and Talaimannar may have been exposed sometime between 7,000 and 18,000 years ago.[19] Thermoluminescence dating by GSI concludes that the dunes between Dhanushkodi and Adam's Bridge started forming about 500–600 years ago.[19]

Another study suggests that the appearance of the reefs and other evidence indicate their recency, and a coral sample gives a radiocarbon age of 4,020±160 years BP.[19] A team from Centre for Remote Sensing (CRS), Bharathidasan University led by S.M. Ramasamy dated the beaches of the Adam's Bridge structure to approximately 3,500 years,[24] concluding that the land/beaches between Ramanathapuram and Pamban were formed due to the longshore drifting currents. About 3,500 years ago, the currents moved in an anticlockwise direction in the north and in the clockwise direction in the south of Rameswaram and Talaimannar.[25] In the same study, carbon dating of some ancient beaches between Thiruthuraipoondi and Kodiyakarai shows the Thiruthuraipoondi beach dates back to 6,000 years and Kodiyakarai around 1,100 years ago.

Early surveys and dredging efforts

Due to shallow waters, Adam's Bridge presents a formidable hindrance to navigation through the Palk Strait. Though trade across the India–Sri Lanka divide has been active since at least the first millennium BC, it was limited to small boats and dinghies. Larger ocean-going vessels from the west have had to navigate around Sri Lanka to reach India's eastern coast.[26] Eminent British geographer Major James Rennell, who surveyed the region as a young officer in the late 18th century, suggested that a "navigable passage could be maintained by dredging the strait of Ramisseram [sic]". However, little notice was given to his proposal, perhaps because it came from "so young and unknown an officer", and the idea was only revived 60 years later.

In 1823, Sir Arthur Cotton (then an Ensign), was assigned to survey the Pamban channel, which separates the Indian mainland from the island of Rameswaram and forms the first link of Adam's Bridge. Geological evidence indicates that a land connection bridged this in the past, and some temple records suggest that violent storms broke the link in 1480. Cotton suggested that the channel could be dredged to enable passage of ships, but nothing was done until 1828 when Major Sim directed the blasting and removal of some rocks.[27][28]

A more detailed marine survey of Adam's Bridge was undertaken in 1837 by Lieutenants F. T. Powell, Ethersey, Grieve, and Christopher along with draughtsman Felix Jones, and operations to dredge the channel were recommenced the next year.[27][29] However, these and subsequent efforts in the 19th century did not succeed in keeping the passage navigable for any vessels except those with a light draft.[2]

Sethusamudram shipping canal project

The Government of India constituted nine committees before independence, and five committees since then, to suggest alignments for a Sethusamudram canal project. Most of them suggested land-based passages across Rameswaram island, and none recommended alignment across Adam's Bridge.[30] The Sethusamudram project committee in 1956 also strongly recommended to the Union government to use land passages instead of cutting Adam's Bridge because of the several advantages of land passage.[31]

In 2005, the Government of India approved a multi-million dollar Sethusamudram Shipping Canal Project. This project aims to create a ship channel across the Palk Strait by dredging the shallow ocean floor near Dhanushkodi. The channel is expected to cut over 400 km (nearly 30 hours of shipping time) off the voyage around the island of Sri Lanka. This proposed channel's current alignment requires dredging through Adam's Bridge.

Indian political parties including the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK), Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD), Janata Dal (Secular) (JD(S)) and some Hindu organisations oppose dredging through the shoal on religious grounds. The contention is that Adam's Bridge is identified popularly as the causeway described in the Ramayana. The political parties and organizations suggest alternate alignment for the channel that avoids damage to Adam's Bridge.[32][33] The then state and central governments opposed such changes, with the Union Shipping Minister T. R Baalu, who belongs to the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam and a strong supporter of the project maintaining that the current proposal was economically viable and environmentally sustainable and that there were no other alternatives.[34][35][36]

Opposition to dredging through this causeway also stems from concerns over its impact on the area's ecology and marine wealth, potential loss of thorium deposits in the area and increased risk of damage due to tsunamis.[37] Some organisations oppose this project on economic and environmental grounds and claim that proper scientific studies were not conducted before undertaking this project.[38]

Origin legends

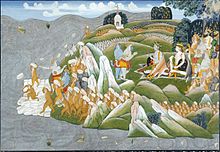

Indian culture and religion include legends that the structure is of supernatural origin. According to the Hindu epic, Ramayana, Ravana, the demon king of Lanka (Sri Lanka) kidnapped Rama's wife Sita and took her to Lankapura, doing this for revenge against Rama and his brother Lakshmana for having cut off the nose of Ravana's sister, Shurpanakha. Shurpanakha had threatened to kill and eat Sita if Rama did not agree to leave her and marry Shurpanakha instead.

To rescue Sita, Rama needed to cross to Lanka. Brahma created an army of vanaras (intelligent warrior monkeys) to aid Rama. Led by Nila and under the engineering direction of Nala, the vanaras constructed a bridge to Lanka in five days. The bridge is also called Nala Setu, the bridge of Nala.[39]

Rama crossed the sea on this bridge and pursued Ravana for many days. He fired hundreds of golden arrows which became serpents that cut off Ravana's heads, but ultimately had to use the divine arrow of Brahma (which had the power of the gods in it and cannot miss its target) to slay Ravana.[40][41] None of the early Ramayana versions provide geographical identifications that directly suggest that Lankapura was Sri Lanka. Versions of the Ramayana reached Sri Lanka in the sixth century but identifications of Sri Lanka with the land of Ravana are first noted in the 8th century inscriptions of southern India. The idea that Sri Lanka was the Lankapura of the Ramayana is thought to have been promoted in the tenth century by Chola rulers seeking to invade the island and the identification of Sri Lanka as Ravana's land was supported by rulers of the Aryacakravarti dynasty who considered themselves guardians of the bridge.[42] The idea of Rama Setu as a sacred symbol to be appropriated for political purposes strengthened in the aftermath of protests against the Sethusamudram Shipping Canal Project.[43]

Controversy over origin

Religious beliefs that the geological structure was constructed by Rama have caused some controversy as believers reject the natural provenance of Adam's Bridge. Some of the more transient structures such as the beaches having ages that are within hundreds or thousands of years (see the above section on age) has provided fodder for speculation. For example, S.M. Ramasamy stated, "as the carbon dating of the beaches roughly matches the dates of Ramayana, its link to the epic needs to be explored".[25] Some have gone even further; S. Badrinarayanan, a former director of the Geological Survey of India,[44][45] a publication of the National Remote Sensing Agency,[46] a spokesman for the Indian government in a 2008 court case,[47] the Madras High Court,[48] and an episode from the Science Channel series What on Earth?[49] have all either explicitly or implicitly claimed that the ancient Hindu myth of Lord Ram building the structure could be literally true, contrary to the scientific facts of the matter.

In the What on Earth? episode, those claiming that Adam's Bridge was constructed based their arguments on vague speculation, false implications, and the point that – as with many geological formations – not every detail of its formation has been incontrovertibly settled.[50] Indian Geologist C. P. Rajendran described the ensuing media controversy as an "abhorrent" example of the "post-truth era, where debates are largely focused on appeals to emotions rather than factual realities".[51] The "skin deep" support by Indian government officials for the mythological origin of the feature was identified by Bharatiya Janata Party politician Tarun Vijay as being politically motivated to placate religious voters.[52]

Other scientists in India and elsewhere have consistently rejected a supernatural explanation for the existence of the structure.[53][54] NASA said that its satellite photos had been egregiously misinterpreted to make this point: "The images reproduced on the websites may well be ours, but their interpretation is certainly not ours. [...] Remote sensing images or photographs from orbit cannot provide direct information about the origin or age of a chain of islands, and certainly, cannot determine whether humans were involved in producing any of the patterns seen."[55]

A report from the Archaeological Survey of India found no evidence for the structure being anything but a natural formation.[19] The Archaeological Survey of India and the government of India informed the Supreme Court of India in a 2007 affidavit that there was no historical proof of the bridge being built by Rama.[56] In 2017 the Indian Council of Historical Research (ICHR) announced that it would conduct a pilot study into the origins of the structure,[57][58] but then, in April 2018, the ICHR announced that it would not conduct or fund any further study to determine whether the Adam’s Bridge was a human-made or a natural structure, stating "It is not the work of historians to carry out excavations and work like that. For that, there are apt agencies such as the Archaeological Survey of India."[59]

In 2007, the Sri Lankan Tourism Development Authority sought to promote religious tourism from Hindu pilgrims in India by including the phenomenon as one of the points on its "Ramayana Trail", celebrating the legend of Prince Rama. Some Sri Lankan historians have condemned the undertaking as "a gross distortion of Sri Lankan history".[60]

See also

- Adam's Bridge Marine National Park

- Ramanathaswamy Temple

- Pamban Bridge

- Kumari Kandam

- Bimini Road

- Coral reefs in India

Notes

References

- ^ also spelled Ram Sethu, Ramasethu and variants.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Adam's bridge". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Archived from the original on 13 January 2008. Retrieved 14 September 2007.

- ^ Garg, Ganga Ram (1992). "Adam's Bridge". Encyclopaedia of the Hindu World. A–Aj. New Delhi: South Asia Books. p. 142. ISBN 978-81-261-3489-2.

- ^ "Ramar Sethu, a world heritage centre?". Rediff.com. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Room, Adrian (2006). Placenames of the World. McFarland & Company. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-7864-2248-7.

- ^ "Valmiki Ramayana - Yuddha Kanda". www.valmikiramayan.net. Archived from the original on 13 December 2017. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- ^ Kumar, Krishna (1994). "The historicity and date of the Ramayana episode: a new approach to the problem". Archív Orientální. 62: 382–400.

- ^ Sankalia, H.D. (1982). The Ramayana in Historical Perspective. Macmillan India. pp. 120–122.

- ^ Nagar, Malti; Nanda, S. C. (1986). "Ethnographic evidence for the location of Ravana's Lanka". Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute. 45: 71–77. ISSN 0045-9801. JSTOR 42930156.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Suckling, Horatio John (1876). Ceylon: A General Description of the Island, Historical, Physical, Statistical. Containing the Most Recent Information. Chapman & Hall. pp. 58.

- ^ "Adams Bridge | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ Ricci, Ronit (2011). Islam Translated: Literature, Conversion, and the Arabic Cosmopolis of South and Southeast Asia. University of Chicago Press. p. 136. ISBN 9780226710884.

- ^ Tennent, James Emerson (1859). Ceylon: An Account of the Island Physical, Historical and Topographical. London: Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts. p. 13.

- ^ Suess, Eduard (1906). The Face of the Earth (Vol. II). Translated by Hertha B. C. Sollas. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 512–513.

- ^ "Ram Setu: Fact or fiction?". www.speakingtree.in. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bahuguna, Anjali; Nayak, Shailesh; Deshmukh, Benidhar (1 December 2003). "IRS views the Adams bridge (bridging India and Sri Lanka)". Journal of the Indian Society of Remote Sensing. 31 (4): 237–239. doi:10.1007/BF03007343. ISSN 0255-660X. S2CID 129785771.

- ^ "Double Tombolo reference by NASA". Archived from the original on 2 December 2007. Retrieved 21 October 2007.

- ^ "Tombolo | geology". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g "Myth vs Science". Frontline. 5 October 2007. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ Crustal downwarping, block faulting, and mantel plume activity view

- ^ Ramasamy, S.M. (2003). "Facts and myths about Adam's Bridge" (PDF). GIS@development.

- ^ D. R. Stoddart; C. S. Gopinadha Pillai (1972). "Raised Reefs of Ramanathapuram, South India". Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. 56 (56): 111–125. doi:10.2307/621544. JSTOR 621544.

- ^ Ripley, S. Dillon; Beehler, Bruce M. (November 1990). "Patterns of Speciation in Indian Birds". Journal of Biogeography. 17 (6): 639–648. doi:10.2307/2845145. JSTOR 2845145.

- ^ CRS study point Ram Setu to 3500 years old

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Rama's bridge is only 3,500 years old: CRS". Indian Express. 2 February 2003. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- ^ Francis Jr., Peter (2002). Asia's Maritime Bead Trade: 300 B.C. to the Present. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2332-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hunter, Sir William Wilson (1886). The Imperial Gazetteer of India. Trübner & co. pp. 21–23.

- ^ Digby, William (1900). General Sir Arthur Cotton, R. E., K. C. S. I.: His Life and Work. Hodder & Stoughton. pp. 15–16.

- ^ Dawson, Llewellyn Styles (1885). Memoirs of hydrography. Keay. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-665-68425-8.

- ^ Sethusamudram Corporation Limited–History Archived 14 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Use land based channel and do not cut through Adam bridge:Sethu samudram project committee report to Union Government". 30 September 2007. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

"In these circumstances we have no doubt, whatever that the junction between the two sea should be effected by a Canal; and the idea of cutting a passage in the sea through Adam's Bridge should be abandoned.

- ^ "Ram Setu a matter of faith, needs to be protected: Lalu". NewKerela.com. 21 September 2007. Retrieved 24 September 2007.

- ^ "Rama is 'divine personality' says Gowda". MangaoreNews.com. 22 September 2007. Archived from the original on 21 April 2008. Retrieved 24 September 2007.

- ^ "IndianExpress.com–Sethu: DMK chief sticks to his stand". Archived from the original on 21 April 2008. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ^ Latest India News @ NewKerala.Com, India[dead link]

- ^ "indianexpress.com". Archived from the original on 21 April 2008. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ^ "Thorium reserves to be disturbed if Ramar Sethu is destroyed". The Hindu. 5 August 2007. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 24 September 2007.

- ^ Karunanidhi or T R Baalu's arguments are not based on scientific studies claims coastal action network convenor

- ^ Nanditha Krishna (1 May 2014). Sacred Animals of India. Penguin Books Limited. p. 246. ISBN 978-81-8475-182-6.

- ^ "Ravana loses his heads". British Library. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ^ Ariel Sophia Bardi (31 May 2017). "God or Geology? The Genesis of Ram's Bridge". Hakai Magazine. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ^ Henry, Justin W. (2019). "Explorations in the Transmission of the Ramayana in Sri Lanka". South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. 42 (4): 732–746. doi:10.1080/00856401.2019.1631739. ISSN 0085-6401. S2CID 201385559.

- ^ Jaffrelot, Christophe (2008). "Hindu Nationalism and the (Not So Easy) Art of Being Outraged: The Ram Setu Controversy". South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal (2). doi:10.4000/samaj.1372. ISSN 1960-6060.

- ^ "Debate shifted over Ram from Ram Sethu". indianewstrack.com. 15 September 2007. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- ^ Ram sethu should be manmade says former Geological survey of India director

- ^ "Ram Sethu 'man-made', says government publication". Sify News. 8 December 2007. Archived from the original on 20 December 2007.

- ^ Ram himself destroyed Setu, govt tells SC

- ^ Ram Sethu Timeline

- ^ Shahane, Girish. "Raptures over Ram Setu video underline what's wrong with our government and sections of the media". Scroll.in. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ "A bridge that Lord Ram built - myth or reality?". DW. Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ C.P. Rajendran. "A Post-Truth Take on the Ram Setu". The Wire. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ "Because it is Ram Setu and not Nehru bridge".

- ^ "Hanuman bridge is myth: Experts". The Times of India. 19 October 2002. Retrieved 6 January 2012.

- ^ "'Place faith in science, and not in faith-based culture'". The Hindu. 6 May 2019. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

popular hegemonic culture had so successfully been able to impress upon many people that even scientific organisations were not ready to explore the myth around Ram Setu

- ^ Kumar, Arun (14 September 2007). "Space photos no proof of Ram Setu: NASA". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 22 January 2008. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

"The mysterious bridge was nothing more than a 30 km long, naturally occurring chain of sandbanks called Adam's bridge", [NASA official Mark] Hess had added. "NASA had been taking pictures of these shoals for years. Its images had never resulted in any scientific discovery in the area.

- ^ "No evidence to prove existence of Ram". Rediff.com. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ "Twenty research scholars to get training to find 'truth' of Ram Sethu". The Indian Express. 25 March 2017. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ "Is Ram Setu man-made? BJP attacks Congress after US channel's findings". The Indian Express. 13 December 2017. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ "ICHR not to conduct study whether Ram Setu man made, natural". The Times of India. 8 April 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- ^ Kumarage, Achalie (23 July 2010). "Selling off the history via the 'Ramayana Trail'". Daily Mirror. Colombo: Wijeya Newspapers Ltd. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. Retrieved 23 July 2010.

the Tourism Authority is imposing an artificial [history] targeting a small segment of Indian travellers, specifically Hindu fundamentalists...

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Adam's Bridge. |

- Coromandel Coast

- Gulf of Mannar

- India–Sri Lanka border

- Landforms of Mannar District

- Landforms of Tamil Nadu

- Locations in Hindu mythology

- Palk Strait

- Transport in Rameswaram

- Places in the Ramayana

- Purana temples of Vishnu

- Ramayana

- Shoals of Asia

- Tombolos