Tombolo

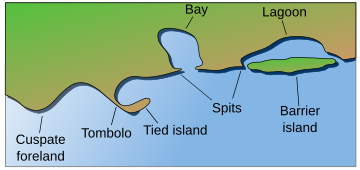

A tombolo is a sandy isthmus. A tombolo, from the Italian tombolo, meaning 'pillow' or 'cushion', and sometimes translated as ayre, is a deposition landform by which an island becomes attached to the mainland by a narrow piece of land such as a spit or bar.[1] Once attached, the island is then known as a tied island.

Several islands tied together by bars which rise above the water level are called a tombolo cluster.[2] Two or more tombolos may form an enclosure (called a lagoon) that can eventually fill with sediment.

Formation[]

The shoreline moves toward the island (or detached breakwater) due to accretion of sand in the lee of the island where wave energy and longshore drift are reduced and therefore deposition of sand occurs.

Wave diffraction and refraction[]

True tombolos are formed by wave refraction and diffraction. As waves near an island, they are slowed by the shallow water surrounding it. These waves then bend around the island to the opposite side as they approach. The wave pattern created by this water movement causes a convergence of longshore drift on the opposite side of the island. The beach sediments that are moving by lateral transport on the lee side of the island will accumulate there, conforming to the shape of the wave pattern. In other words, the waves sweep sediment together from both sides. Eventually, when enough sediment has built up, the beach shoreline, known as a spit, will connect with an island and form a tombolo.[3]

Unidirectional longshore drift[]

In the case of longshore drift due to an oblique wave direction, like at Chesil Beach or Spurn Head, the flow of material is along the coast in a movement which is not determined by wave diffraction around the now tied island, such as Portland, which it has reached. In this and similar cases like Cadiz, while the strip of beach material connected to the island may be technically called a tombolo because it links the island to the land, it is better thought of in terms of its formation as a spit, because the sand or shingle ridge is parallel rather than at right angles to the coast.

Morphology and sediment distribution[]

Tombolos demonstrate the sensitivity of shorelines. A small piece of land, such as an island, or a beached shipwreck can change the way that waves move, leading to different deposition of sediments. Sea level rise may also contribute to accretion, as material is pushed up with rising sea levels. Tombolos are more prone to natural fluctuations of profile and area as a result of tidal and weather events than a normal beach is. Because of this susceptibility to weathering, tombolos are sometimes made more sturdy through the construction of roads or parking lots. The sediments that make up a tombolo are coarser towards the bottom and finer towards the surface. It is easy to see this pattern when the waves are destructive and wash away finer grained material at the top, revealing coarser sands and cobbles as the base.

List of tombolos[]

- Adam's Bridge (until 1480), between India and Sri Lanka

- The Angel Road of Shodo Island, Japan

- Aupouri Peninsula, New Zealand

- Barrenjoey Headland, Pittwater, New South Wales, Australia

- Beavertail Point, Conanicut Island, Rhode Island, United States

- Bennett Island, De Long Group, Russia

- Biddeford Pool, Maine, United States[4]

- Bijia Mountain, China

- Bruny Island, Tasmania, Australia

- Burgh Island, Devon, England

- Cádiz, Andalucía, Spain

- Chappaquiddick Island, Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts, United States

- Charles Island, Connecticut, United States

- Chesil Beach, Portland, Dorset, England

- Cheung Chau, Hong Kong

- Crimea, Ukraine

- Eaglehawk Neck, Tasmania, Australia

- S'Espalmador, Formentera, Spain

- Fingal Bay, New South Wales, Australia

- The Rock of Gibraltar

- Grand Island National Recreation Area, Michigan, United States

- Gugh, St Agnes, Isles of Scilly, England

- Gwadar, Pakistan

- Hakodate, Hokkaido, Japan

- Howth Head, Dublin, Ireland

- Inishkeel Island, Narin, Ireland

- Kapıdağ Peninsula, Balıkesir, Turkey

- Knappelskär, Nynäshamn, Sweden

- Kurnell, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

- Lake Pomorie, Bulgaria

- Langness, Derbyhaven, Isle of Man

- Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Canary Islands, Spain

- Llandudno, North Wales

- Louds Island at Muscongus Bay, Maine, United States

- Maharees, Dingle Peninsula, Ireland

- Mare Island, Vallejo, California, United States

- Maria Island, Tasmania

- Maury Island, Washington, United States

- McMicken Island State Park, Washington, United States

- Miquelon, Saint-Pierre and Miquelon, France

- Monemvasia, Laconia, Peloponnese, Greece

- Monte Argentario, Tuscany, Italy

- Mont-Saint-Michel, Normandy, France

- Moses' Pass (Whale Tail), Ballena National Marine Park, Uvita, Costa Rica

- Mount Maunganui, New Zealand

- Mount Taipingot, Rota, Northern Marianas

- Nahant, Massachusetts, United States (a natural tombolo, but connected to the mainland by a causeway)

- Nissi beach, Ayia Napa, Cyprus

- Ormara, Pakistan

- Palisadoes, Kingston, Jamaica

- Peniche, Portugal

- Peniscola, Castellon, Spain

- Porchat Island, Itararé Beach, São Vicente, Brazil[citation needed]

- Presqu'ile Provincial Park, Ontario, Canada

- Pulau Konet, Masjid Tanah, Melaka, Malaysia

- Presqu'ile de Giens, Hyères, France

- Quiberon, France

- Sainte-Marie, Martinique, France

- Scotts Head, Dominica

- Shaman's Island, Douglas, Alaska, United States

- Sharp Island, Sai Kung District, Hong Kong

- Silver Strand (San Diego), Coronado, California, United States

- St Michael's Mount, Cornwall, England

- St Ninian's Isle, Shetland Islands, Scotland

- Sveti Stefan, near Budva, Montenegro

- Tam Hai, Quang Nam province, Vietnam

- University Beach, Ward Island, Corpus Christi, Texas, United States

- Uummannaq in North Star Bay, Greenland

- Yei of Huney, Huney, Shetland Islands, Scotland

- Zhifu Island, Yantai, China

Some of these may be simple isthmus, and not have the deposition creation that defines a true tombolo.[6]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ De Mahiques, Michel Michaelovitch (2016). "Tombolo". Encyclopedia of Estuaries. Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series. pp. 713–714. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-8801-4_349. ISBN 978-94-017-8800-7.

- ^ Glossary of Geology and Related Sciences. The American Geological Institute, 1957

- ^ Easterbrook, Don T. Surface Processes and Landforms, Second Edition. 1999 Prentice Hall Inc.

- ^ Neal, William; Orrin H. Pilkey; Joseph T. Kelley (2007). Atlantic Coast Beaches: A Guide to Ripples, Dunes, and Other Natural Features of the Seashore. Missoula, MT: Mountain Press Publishing Company. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-87842-534-1.

- ^

- ^ Owens, Edward H. (1982). Beaches and Coastal Geology. Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series. pp. 838–839. doi:10.1007/0-387-30843-1_474. ISBN 978-0-87933-213-6.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tombolos. |

- Geology.About.com's page on tombolos (useful for its descriptive photograph)

- Tombolo in Sainte-Marie, Martinique (useful for its photos and description)

- further reading on Detached breakwaters from Vlaams Instituut voor de Zee in Belgium

- further reading on coastal structures from Prof. Leo van Rijn in Holland

- Coastal and oceanic landforms

- Coastal geography

- Tombolos

- Oceanographical terminology