Akzidenz-Grotesk

| |

| Category | Sans-serif |

|---|---|

| Classification | Grotesque |

| Foundry | H. Berthold AG[1] |

| Date released | 1898 |

Akzidenz-Grotesk is a sans-serif typeface family originally released by the Berthold Type Foundry of Berlin. "Akzidenz" indicates its intended use as a typeface for commercial print runs such as publicity, tickets and forms, as opposed to fine printing, and "grotesque" was a standard name for sans-serif typefaces at the time.

Originating during the late nineteenth century, Akzidenz-Grotesk belongs to a tradition of general-purpose, unadorned sans-serif types that had become dominant in German printing during the nineteenth century. Relatively little-known for a half-century after its introduction, it achieved iconic status in the post-war period as the preferred typeface of many Swiss graphic designers in what became called the 'International' or 'Swiss' design style which became popular across the Western world in the 1950s and 1960s. Its simple, neutral design has also influenced many later typefaces. It has sometimes been sold as Standard or Basic Commercial in English-speaking countries, and a variety of digital versions have been released by Berthold and other companies.

Etymology[]

Akzidenz-Grotesk is often translated into English as "jobbing sans-serif", "jobbing" in the sense of "used for jobs".[2] Both words were everyday, descriptive terms for typefaces of the time in the German language.

Akzidenz means some occasion or event (in the sense of "something that happens", not in the sense of a high-class social event or occasion)[3] and was therefore used as a term for trade printing; Akzidenzschrift was by the 1870s a generic term meaning typefaces intended for these uses.[3][4] A modern German-language dictionary describes it as work such as advertisements and forms.[5][6] The origin of the word is Latin accidentia, defined by Lewis and Short as "that which happens, a casual event, a chance".[3][7]

Grotesque (German: Grotesk) was a standard term that had become popular in the first half of the nineteenth century for sans-serifs. It was introduced by the London type-founder William Thorowgood as the name for sans-serifs in the specimen books of his Fann Street Foundry around 1830.[8] The name may have reflected the "primitive" feel of sans-serifs, or their roots in archaic Greek and Roman inscriptions, and by the late nineteenth century was commonly used to mean "sans-serif", without negative implication.[8]

Design characteristics[]

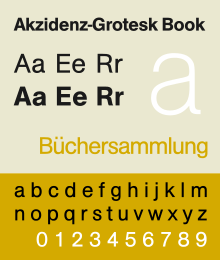

Like most sans-serifs, Akzidenz-Grotesk is 'monoline' in structure, with all strokes of the letter of similar width. This gives a sense of simplicity and an absence of the adornment and flourishes seen in the more decorative sans-serifs of the late nineteenth century influenced by the Art Nouveau style.[9] Modern type designer Martin Majoor has described the general design of Akzidenz-Grotesk and its ancestors as similar in letterforms to the Didone serif fonts that were standard printing types in the nineteenth century, such as Didot, Walbaum and their followers.[10] This is most visible in the quite folded-up apertures of letters such as ‘a’ and ‘c’.[10] The capitals of Akzidenz-Grotesk are wide and relatively uniform in width.[8]

The 'g' of Akzidenz-Grotesk is a 'single-storey' design, like in many other German sans-serifs, but unlike the double-storey 'g' found in most serif faces and in many of the earliest sans-serifs that had a lower-case; sans-serif types first appeared in London, but became popular in Germany from the mid-nineteenth century onwards.[11][12] Walter Tracy describes this style of 'g' as a common feature in German sans-serifs of the period and apparently influenced by the tradition of blackletter, still very popular for printing extended texts in Germany in the late nineteenth century, which uses a single-storey 'g' in upright composition.[13]

The metal type of Akzidenz-Grotesk shows variation between sizes, with adaptation of letter-spacing and proportions such as looser spacing at smaller text sizes, something that was normal practice in the design and engraving of metal type.[14][15][16] In addition, there is variation between weights: Karl Gerstner notes that even comparing one size (20pt), the medium and bold weights have different x-height, cap height and descender length to the light and regular weights.[14][17] This is common with nineteenth-century sans-serifs, which were not designed with the intention of forming an extended family that would match together.[18][3] (Berthold literature from the 1900s marketed the light and regular weights as being compatible, light at the time called 'Royal-Grotesk'.[19]) The differences in proportions between different sizes and weights of Akzidenz-Grotesk has led to a range of contemporary adaptations, reviving or modifying different aspects of the original design, discussed below.

Early history[]

Akzidenz-Grotesk's design descends from a school of general-purpose sans-serifs cut in the nineteenth century.[23] Sans-serifs had become very popular in Germany by the late nineteenth century, which had a large number of small local type foundries offering different versions.[24][11]

H. Berthold was founded in Berlin in 1858 initially to make machined brass printer's rule, moving into casting metal type particularly after 1893.[25][26] Berthold publications from the 1920s onwards dated the design to 1898,[27][11][28] when the firm registered two design patents on the family.[29][30]

Recent research by historians Eckehart Schumacher-Gebler, Indra Kupferschmid and Dan Reynolds has clarified many aspects of Akzidenz-Grotesk's history. The source of Akzidenz-Grotesk appears to be Berthold's 1897 purchase of the Bauer u. Cie Type Foundry of Stuttgart (not to be confused with the much better-known Bauer Type Foundry of Frankfurt); Kupferschmid concludes that the design appears to be related to a shadowed sans-serif (German: Schattierte Grotesk) sold by the Bauer Foundry and reviewed in a printing journal in 1896.[20] Two design patents on Akzidenz-Grotesk were filed in April 1898, first on the 14th in Stuttgart by Bauer and then on the 28th in Berlin by Berthold, leading Reynolds to conclude that the design was executed in Stuttgart.[30] Some early adverts that present Akzidenz-Grotesk are co-signed by both brands.[31][32][33] Early references to Akzidenz-Grotesk at Berthold often use the alternative spelling 'Accidenz-Grotesk'; Reynolds suggests that the name may have been intended as a brand extension following on from an "Accidenz-Gothisch" blackletter face sold by the Bauer & Co. foundry.[34][35] In general, Reynolds comments that the style of Schattierte Grotesk and Akzidenz-Grotesk "seem to me to be more of a synthesis of then-current ideas of sans serif letterform design, rather than copies of any specific products from other firms."[3]

The light weight of Akzidenz-Grotesk was for many years branded separately as 'Royal-Grotesk'. It apparently was cut by Berthold around 1902-3, when it was announced in a trade periodical as "a new, quite usable typeface" and advertised as having matching dimensions allowing it to be combined with the regular weight of Akzidenz-Grotesk.[28][36][19][27] Reynolds and Florian Hardwig have documented the Schmalhalbfett weight (semi-bold, or medium, condensed) to be a family sold by many German type-foundries, which probably originated from a New York type foundry.[37][38][39]

Günter Gerhard Lange, Berthold's post-war artistic director, who was considered effectively the curator of the Akzidenz-Grotesk design, said in a 2003 interview Akzidenz-Grotesk came from the Ferdinand Theinhardt type foundry, and this claim has been widely copied elsewhere.[40] This had been established by businessman and punchcutter Ferdinand Theinhardt, who was otherwise particularly famous for his scholarly endeavours in the field of hieroglyph and Syriac typefaces; he had sold the business in 1885.[41][42][43] Kupferschmid and Reynolds speculate that he was misled by Akzidenz-Grotesk appearing in a Theinhardt foundry specimen after Berthold had taken the company over.[44][25][45][46][47][28][20][32][48] Reynolds additionally points out that Theinhardt sold his foundry to Oskar Mammen and Robert and Emil Mosig in 1885, a decade before Akzidenz-Grotesk was released, and there is no evidence that he cut any further fonts for them after this year.[43] As Lange commented, it was claimed in the post-war period that Royal-Grotesk's name referred to it being commissioned by the Prussian Academy of Sciences, but Kupferschmid was not able to find it used in its publications.[28]

Many other grotesques in a similar style to Akzidenz-Grotesk were sold in Germany during this period. Around the beginning of the twentieth century, these increasingly began to be branded as larger families of multiple matched styles.[3][49] Its competitors included the very popular Venus-Grotesk of the Bauer foundry of Frankfurt, very similar to Akzidenz-Grotesk but with high-waisted capitals, and Koralle by Schelter & Giesecke, which has a single-storey 'a'.[50][51][b] (Monotype Grotesque 215 also is based on German typefaces of this period.[53]) Seeman's 1926 Handbook of Typefaces (German: Handbuch der Schriftarten), a handbook of all the metal typefaces available in Germany, illustrates the wide range of sans-serif typefaces on sale in Germany by the time of its publication.[54][27] By around 1911, Berthold had begun to market Akzidenz-Grotesk as a complete family.[55][28][32]

While apparently not unpopular, Akzidenz-Grotesk was not among the most intensively-marketed typefaces of the period, and was not even particularly aggressively marketed by Berthold.[14] A 1921 Berthold specimen and company history described it almost apologetically: "In 1898 Accidenz-Grotesk was created, which has earned a laurel wreath of fame for itself. This old typeface, which these days one would perhaps make in a more modern style, has a peculiar life in its own way which would probably be lost if it were to be altered. All the many imitations of Accidenz-Grotesk have not matched its character."[35] An unusual user of Berthold's Akzidenz-Grotesk in the period soon after its release, however, was the poet Stefan George.[56] He commissioned some custom uncial-style alternate characters to print his poetry.[57][58][59]

Mid-twentieth-century use[]

The use of Akzidenz-Grotesk and similar "grotesque" typefaces dipped from the late 1920s due to the arrival of fashionable new "geometric" sans-serifs such as Erbar, Futura and Kabel, based on the proportions of the circle and square. Berthold released its own family in this style, Berthold-Grotesk.[c]

However, during this period there was increasing interest in using sans-serifs as capturing the spirit of the time, most famously, Jan Tschichold's influential book The New Typography (German: Die Neue Typographie), which praised the aesthetic qualities of the "anonymous" sans-serifs of the nineteenth century[63] and was printed in a sans-serif similar to Berthold's Akzidenz-Grotesk.[d] Its comments would prove influential in later graphic design:

Among all the types that are available, the so-called "Grotesque"...is the only one in spiritual accordance with our time. To proclaim sans-serif as the typeface of our time is not a question of being fashionable, it really does express the same tendencies to be seen in our architecture…there is no doubt that the sans-serif types available today are not yet wholly satisfactory as all-purpose faces. The essential characteristics of this type have not been fully worked out: the lower-case letters especially are still too like their "humanistic" counterparts. Most of them, in particular the newest designs such as Erbar and Kabel, are inferior to the old anonymous sans-serifs, and have modifications which place them basically in line with the rest of the "art" faces. As bread-and-butter faces they are less good than the old sans faces...I find the best face in use today is the so-called ordinary jobbing sanserif, which is quiet and easy to read.[65]

The Swiss style[]

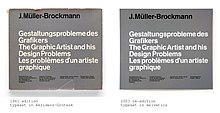

In the post-war period and particularly in Switzerland a revival in Akzidenz-Grotesk's popularity took hold, in what became known as the "Swiss International Style" of graphic design. This style often contrasted Akzidenz-Grotesk with photographic art, and did not use all caps as much as many older posters.[66] Graphic designers of this style such as Gerstner, Josef Müller-Brockmann and Armin Hofmann all used Akzidenz-Grotesk heavily.[67][68][69] Like Tschichold, Gerstner argued that the sans-serifs of the nineteenth century were more "matter-of-fact" (German: Selbstverständlichkeit) than the more "personal" recent sans-serifs of the previous decades.[14][15] Art historian Stephen Eskilson wrote that they "conveyed the functionalist ethos without appearing too stylised...in the manner of the more geometrically pure types."[66] Berthold suggested in the 1980s that the originator of this use of Akzidenz-Grotesk in Zürich was German-born designer Anton Stankowski.[70]

Akzidenz-Grotesk was popular in this period although other typefaces such as Monotype Grotesque were used also: a problem with use of Akzidenz-Grotesk up to the late 1950s was that it was only available in individual units of metal type for manual composition. While this was acceptable for posters, by the 1950s hot metal typesetting machines had long since become the main system for printing general-purpose body text, and for machine composition Akzidenz-Grotesk was unavailable until around 1958,[e] when it was first sold on Linotype and then in 1960 on Intertype systems.[73][74] Much printing around this time of body text accordingly used Monotype Grotesque as a lookalike.[75][76][77][52] In the United States, Akzidenz-Grotesk was imported by Amsterdam Continental Types under the name 'Standard', and became quite popular. According to Paul Shaw, "exactly when Amsterdam Continental began importing Standard is unclear but it appears on several record album covers as early as 1957."[78][79][80]

In 1957, three notable competitors of Akzidenz-Grotesk appeared intended to compete with its growing popularity: Helvetica from the Haas foundry, with a very high x-height and tight letterspacing, Univers from Deberny & Peignot, with a large range of weights and widths, and Folio from Bauer.[74] Shaw suggests that Helvetica "began to muscle out" Akzidenz-Grotesk in New York from around summer 1965, when Amsterdam Continental's marketing stopped pushing Standard strongly and began to focus on Helvetica instead.[81]

By the 1960s, Berthold could claim in its type specimens that Akzidenz-Grotesk was:

a type series which has proved itself in practice for more than 70 years and has held its ground to the present day against all comers...wherever one sees graphics and advertising of an international standard...starting a revival in Switzerland in recent years, Akzidenz-Grotesk has progressed all over the world and impressed its image in the typography of our time.[82][83]

Post-metal releases[]

Metal type declined in use from the 1950s onwards, and Akzidenz-Grotesk was rereleased in versions for the new phototypesetting technology, including Berthold's own Diatype,[84] and then digital technologies.[85]

Contemporary versions of Akzidenz-Grotesk descend from a late-1950s project, directed by Lange at Berthold, to enlarge the typeface family.[85] This added new styles including AG Extra (1958), AG Extra Bold (1966) and AG Super (1968), AG Super Italic (2001) and Extra Bold italic (2001).[86][85] Berthold ceased to cast type in 1978.[87]

Separately, Gerstner and other designers at his company GGK Basel launched a project in the 1960s to build Akzidenz-Grotesk into a coherent series, to match the new families appearing in the same style; it was used by Berthold for its Diatype system in the late 60s under the name of "Gerstner-Programm" but according to Lange it was never fully released.[14][88][89][90] A digitisation has been released by the digital type foundry Forgotten Shapes.[91]

The current holder of the Berthold rights is Berthold Types of Chicago, following the bankruptcy of H. Berthold AG of Germany in 1993.[92][93] Berthold released Akzidenz-Grotesk in OpenType format in 2006, under the name Akzidenz-Grotesk Pro, and added matching Cyrillic and Greek characters the next year.[94][95]

Reception[]

As described above, many influential graphic designers have used Akzidenz-Grotesk. In 2013, Pentagram partner Domenic Lippa rated Akzidenz-Grotesk as "probably the best typeface ever designed...it doesn’t overdominate when used, allowing the designer more freedom and versatility".[97] Kris Sowersby has written that he found the semi-bold and bold weights most satisfying.[98] Lange commented that the light weight "was my favourite font from the beginning. I used it on my first Berthold business card and my letterhead. It's a delicate, slender piece of engraving."[99]

A particular criticism of Akzidenz-Grotesk however, has often been that the regular weight has capitals that look unbalanced relative to the lower-case, as shown on the cover of Designing Programmes, which is problematic in extended text. Adrian Frutiger commented that Akzidenz-Grotesk forms "patches in print";[100] Reynolds that in a digital version "the capital letters are slightly too dark, and slightly too close to the lowercase letters that follow them in a word"[101] and Wolfgang Homola that in Helvetica "the weight of the stems of the capitals and the lower case is better balanced".[102]

Distinctive characteristics[]

Characteristics of this typeface are:

lower case: A 'folded-up' structure with narrow apertures and strokes curled up towards the vertical, most obvious on letters such as c, e, s and a.[10] Stroke endings, though, are less consistently horizontal or vertical than in Helvetica. A square dot over the letter i, double-storey a.[105] Single-storey g.[106]

upper case: G with a vertical spur.[105] The capitals are wide and have relatively little variation in width, with letters like 'E' and 'F' quite wide.[8][107] The 'M' is straight-sided with the diagonals meeting in the bottom centre of the letter.[105] Capitals in several weights have very noticeably thicker strokes than the lower-case.[108][101] On many but not all styles a straight leg on the 'R' and a 'Q' where the outstroke does not cut through the letter.[109]

number: A top serif on the 1 and in some styles a downward-pointing serif on the top left of the 7.[109]

It is important to note, however, that as the weights and sizes of Akzidenz-Grotesk were cut separately not all these features will appear on all styles.[82] For instance, the 't' of the Schmalhalbfett weight only has no base, as it was designed separately and not by Berthold.[3]

Akzidenz-Grotesk did not have italics until the post-war period.[3] Its slanted form is an oblique rather than a true italic.[110] This means that the letters are slanted without using handwriting forms.[10] During the metal type period, when italics for Akzidenz-Grotesk were not available, Amsterdam Continental marketed those of an unrelated typeface, Mercator, as companions instead.[3]

Versions[]

Metal type versions[]

Berthold's Akzidenz-Grotesk family by the late metal type period included the following styles. English names are taken from Berthold's Type Specimen (German: Schriftprobe) No. 473 except where stated otherwise:

- Akzidenz-Grotesk (Standard, available on Linotype in modified form as series 57 with oblique)[82][71][g]

- Halbfett (Medium or literally semi-bold, available on Linotype in modified form as series 58 and as poster type)[82][71][h]

- Mager (Light, sometimes sold as Royal-Grotesk)[82][73]

- Fett (Bold, available as poster type)[82][73]

- Schmalmager (Light Condensed)[82][73]

- Eng (Condensed)[82][73]

- Schmalhalbfett (Medium Condensed,[3] originally called "Steinschrift eng".[i] Not designed by Berthold.[111][35] The 'R' has a curled leg and in metal type the 't' no base.[82][73])

- Schmalfett (Bold Condensed,[3][111][35] originally called "Bücher-Grotesk halbfett".[j] Available as poster type, 'R' with a curled leg)[82][73]

- Extra (Extrabold Condensed, tighter-spaced than the Schmalfett weight)[82]

- Extrafett (Compact, or literally, also extra-bold)[82][k]

- Skelett (Extralight Extended)[82][73]

- Breitmager (Light Extended)[82][73]

- Breit (Extended)[82]

- Breithalbfett (Medium Extended, or literally Semi-bold Extended)[82][l][73]

- Breitfett (Extrabold Extended, or literally Bold Extended)[82][m][73]

Reynolds prefers 'Bold Condensed' to describe the Schmalhalbfett and 'Condensed Heavy' for the Schmalfett.[3] Other weights were added by the time of the phototypesetting and digital versions, such as the ultra-bold 'Akzidenz-Grotesk Super'.[86]

Akzidenz-Grotesk Buch[]

Akzidenz-Grotesk Book (German: Buch) is a variant designed by Lange between 1969 and 1973. Designed after Helvetica had become popular, it incorporates some of its features, such as strike-through tail in 'Q', a curved tail for the 'R', horizontal and vertical cut stroke terminators.[112] As in some Helvetica versions, the cedilla is replaced with a comma.[113] Former Berthold font designer Erik Spiekermann has called Lange's "answer to Helvetica."[114] Late in life Lange made no apology for it, commenting when asked about a design alleged to be a copy of one of his own original designs: "there are also people who say that the best Helvetica is my AG Book."[115]

Digital versions included Greek and Cyrillic characters, and the family includes a condensed, extended, rounded and stencil series.[116][117]

Akzidenz-Grotesk Schulbuch[]

Akzidenz-Grotesk Schoolbook (German: Schulbuch) is a 1983 variant of Akzidenz-Grotesk Buch also designed by Lange.[118] It uses schoolbook characters, characters intended to be more distinct and closer to handwritten forms to be easier for children to recognise.[119]

Generally based on Akzidenz-Grotesk Book, it includes a single-storey 'a', curled 'l', lower- and upper-case 'k' that are symmetrical, and 't', 'u' and 'y' without curls on the base.[120] The 'J' has a top bar, the 'M' centre does not descend to the baseline and the 'G' and 'R' are simplified in the manner of Futura.[120] A particularly striking feature is a blackletter-style default upper-case 'i' with a curl at the bottom: this is rarely encountered in the English-speaking world (it would more commonly be recognized as a J), but much more common in Germany.[121][122]

Each weight is available in two fonts featuring alternative designs. In 2008, OpenType Pro versions of the fonts were released. FontFont's FF Schulbuch family is in a similar style.[122]

Akzidenz-Grotesk Old Face[]

Akzidenz-Grotesk Old Face, designed by Lange and released in 1984, was intended to be more true to the metal type than previous phototypesetting versions and incorporate more of the original type's inconsistencies of dimensions such as x-height.[123][90] It also incorporates a comma-style cedilla in the medium and bold weights, inward hook in regular-weighted ß, and a shortened horizontal serif on the regular-weighted 1.[70]

Regular, medium, bold, outline, bold outline and shaded styles were made for the family, but no obliques.[123][70] Berthold promoted the series with a brochure designed by Karl Duschek and Stankowski.[70]

Akzidenz-Grotesk Next[]

In December 2006, Berthold announced the release of Akzidenz-Grotesk Next.[124] Designed by Bernd Möllenstädt and Dieter Hofrichter, this typeface family features readjusted x-heights and weights throughout the family, giving a more consistent design.[124] The family consists of 14 variants with 7 weights in roman and italic, in a single width.[124]

Similarities to other typefaces[]

Several type designers modelled typefaces on this popular typeface in the 1950s; Reynolds comments that the original Akzidenz-Grotesk has limitations in extended text: "the capital letters are slightly too dark."[101] Max Miedinger at the Haas Foundry used it as a model for the typeface Neue Haas-Grotesk, released in 1957 and renamed Helvetica in 1961. Miedinger sought to refine the typeface making it more even and unified, with a higher x-height, tighter spacing and generally horizontal terminals.[74] Two other releases from 1957, Adrian Frutiger's Univers and Bauer's Folio, take inspiration from Akzidenz-Grotesk; Frutiger's goal was to eliminate what he saw as unnecessary details, removing the dropped spur at bottom right of the G and converting the '1' and the '7' into two straight lines.[125][126]

Much more loosely, Transport, the typeface used on British road signs, was designed by Jock Kinneir and Margaret Calvert influenced by Akzidenz-Grotesk.[127] However, many adaptations and letters influenced by other typefaces were incorporated to increase legibility and make characters more distinct.[128][129]

"Akzidenz-Grotesk" (Haas)[]

A completely different "Akzidenz-Grotesk" was made by the Haas Type Foundry of Switzerland. Also named "Accidenz-Grotesk" and "Normal-Grotesk", it had a more condensed, "boxy" design.[66][74] Kupferschmid describes it as a "reworking of "Neue Moderne Grotesk", originally ca. 1909 by Wagner & Schmidt, Leipzig"[130][131] The Haas Foundry created Helvetica in response to its decline in popularity in competition with Berthold's design.[66]

Alternative digitisations[]

Although the digital data of Berthold releases of Akzidenz-Grotesk is copyrighted, and the name is trademarked,[132][133] the design of a typeface is in many countries not copyrightable, notably in the United States, allowing alternative interpretations under different names if they do not reuse digital data.[134][135][136]

The Swiss digital type foundry Optimo has released an alternative digitisation of Akzidenz-Grotesk named "Theinhardt", which Spiekermann has praised as "the best" Akzidenz-Grotesk digitisation.[137][138] Linotype, which started to sell Akzidenz-Grotesk on its hot metal typesetting system in the 1950s, continues to sell a limited digital version under the other common alternative name, 'Basic Commercial', and Bitstream offer a two-weight version named 'Gothic 725'.[139][140] The American publisher CastleType has released a digitisation originally created for San Francisco Focus magazine under the name "Standard CT".[141] A digitisation named Söhne, in three widths with a monospaced version was released by Kris Sowersby in 2019.[98][3][142][143] A proprietary digitisation named NYC Sans by Nick Sherman and Jeremy Mickel, which has many alternate characters, is the corporate font of New York City's tourist board NYC & Company.[144][145][146][147]

Transport has also been digitised in several versions.[148][127] Spiekermann has also released with Ralph du Carrois a very loose digitisation of Akzidenz Grotesk, FF Real, in two optical sizes, with variant features like a two-storey 'g', ligatures, and a true italic.[149][150] A digitisation of Stefan George-Schrift by Colin Kahn has been published by P22.[151]

Notable users[]

Besides use in Swiss-style poster design and in New York City transportation, Akzidenz-Grotesk is the corporate font of Arizona State University[152] and the American Red Cross (with Georgia).[153] Akzidenz-Grotesk Bold Extended is used as the official font for the words "U.S. Air Force" in the display of the USAF symbol.[154]

Berthold sued Target Corporation for copyright infringement and breach of contract in 2017, alleging that Target had asked a design firm to use the font in a promotional video without a license.[155]

See also[]

- Berthold Akzidenz Dialog System

Notes[]

- ^ The display face appears to be Berthold's Herold.[22]

- ^ According to Kupferschmid, Ideal-Grotesk, a separate sans-serif face Berthold sold in the first half of the twentieth century, is a Venus knockoff, possibly made by electrotype copying.[52]

- ^ Berthold-Grotesk is somewhat less well-known than other German geometrics of the period. A licensed adaptation (changing some characters) by the Amsterdam Type Foundry under the name of Nobel, however, became a popular standard typeface in Dutch printing.[60][61] Some twentieth-century sources used different terminology to distinguish between the traditional "grotesques/gothics" and the new faces of the 1920s, such as restricting the term "sans-serifs" to the latter group.[62] The term "industrial" has also been used for the early grotesque sans-serifs like Akzidenz-Grotesk.[53]

- ^ Although similar, according to Kupferschmid the type used in Die Neue Typographie is not Berthold's Akzidenz-Grotesk.[64]

- ^ Date according to Helvetica Forever and Ulrich Stiehl shows Linotype sales material saying that it was "taken over to the Linotype machine" in 1958, although Eskilson reports 1959 for its release.[71][72]

- ^ This image shows a later revival of Walbaum's work; during the early nineteenth century figures in roman type were customarily of variable height.

- ^ An alternative 'R' with curled leg was available by request.[82]

- ^ An alternative 'R' with curled leg was available by request.[82]

- ^ Or Enge Steinschrift

- ^ Or Halbfette Bücher-Grotesk

- ^ Ulrich Stiehl suggests that this may have been one of the last additions to the metal type family: it does not appear in a 1959 advert[73] or Berthold's Hauptprobe Nr. 470, but it does in the slightly later Schriftprobe Nr. 473, which he suggests dates from c. 1966.[82]

- ^ A less folded-up 'a' and 'g' and a narrower 'r' were available by request.[82]

- ^ A less folded-up 'a' and 'g' and a narrower 'r' were available by request.[82]

References[]

- ^ Reynolds, Dan (12 April 2018). "The 1869–1978 headquarters of Berthold today". Typeoff. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ Hollis 2006, p. 24.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Reynolds, Dan (11 November 2019). "New details about the origins of Akzidenz-Grotesk". Klim Type Foundry. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ Marahrens, August, ed. (1870). Vollständiges theoretisch-praktisches Handbuch der Typographie nach ihrem heutigen Standpunkt, zweiter Band: Das Drucken in seinen verschiedenen Branchen. Verlag d. Leipziger Vereinsdruckerei. p. 431.

- ^ Muthmann, Gustav (2000). Handbuch zur neuen Rechtschreibung und Zeichensetzung : für Studierende und Lehrende an Schulen und Universitäten sowie für alle an der Sprache Interessierten. Schöningh. p. 254. ISBN 9783506741097.

Drucksache von geringem Umfang, Anzeige, Formular

- ^ Hardwig, Florian (2 August 2018). ""Herzlichen Glückwunsch" wedding cards (1919)". Fonts in Use. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ Lewis, Charlton Thomas; Short, Charles (1922). A Latin Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 16.

- ^ a b c d Berry, John. "A Neo-Grotesque Heritage". Adobe Systems. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

With its horizontal and vertical strokes of almost the same thickness and its regularized capital letters with few variations of width, Akzidenz Grotesk stood out starkly on the page – especially when that page also included the highly-decorated types that were popular in the same era.

- ^ Homola 2004, p. 29.

- ^ a b c d Majoor, Martin. "My Type Design Philosophy". Typotheque. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ^ a b c Handover, Phyllis Margaret (1958). "Grotesque Letters". Monotype Newsletter, Also Printed in Motif as "Letters Without Serifs".

- ^ Mosley, James. "Comments on Typophile thread – "Unborn: sans serif lower case in the 19th century"". Typophile (archived). Archived from the original on 28 June 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2016.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- ^ Tracy 2003, p. 58.

- ^ a b c d e f Gerstner, Karl (1963). "A new basis for the old Akzidenz-Grotesk (English translation)" (PDF). Der Druckspiegel. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-10-15. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ a b Gerstner 1963, p. 5.

- ^ Frere-Jones, Tobias. "MicroPlus". Frere-Jones Type. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ^ Gerstner 1963, p. 7.

- ^ Hoefler, Jonathan; Frere-Jones, Tobias. "Knockout". Hoefler & Co. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

The notion of the "type family" is so central to typography that it's easy to forget how recent an invention it is. Throughout most of its history, typography simply evolved the forms that were the most useful and the most interesting, generally with indifference toward how they related to one another. Italic faces existed for decades before they were considered as companions for romans, just as poster types shouted in a range of emphatic tones before they were reimagined as "bold" or "condensed" cousins. The notion that a type family should be planned from the outset is a Modernist concoction, and it's one that type designers have lived with for less than a century…For more than a century before Helvetica, the sans serif landscape was dominated by unrelated designs.

- ^ a b "Schriftprobe". Archiv für Buchgewerbe. 41: 149. 1904. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

Die Firma H. Berthold, Akt-Ges. in Berlin zeigt in einem hübsch angeordneten handlichen Heftchen zwei Garnituren Royal- und Akzidenz-Grotesk, beide sich ergänzende Schriften von vornehmer Wirkung, die um so mehr als zeitgemäß bezeichnet werden können, weil anscheinend nun endlich auch in der Druckausstattung der Akzidenzen Wege eingeschlagen werden, die zu einer wesentlichen Vereinfachung des Satzbildes führen dürften.

- ^ a b c "Schriftprobenschau". Archiv für Buchdruckerkunst und verwandte Geschäftszweige: 404, 407. 1896.

Die Schriftgießerei Bauer & Co., Stuttgart und Düsseldorf, veröffentlicht unter den heutigen Schriftproben eine schattierte Grotesk und bietet unseren Lesern mit dieser Schrift ein beliebtes, sehr verwendbares Material, das sich in ähnlicher, älterer Ausführung seit jener einen Platz auf allen guten Akzidenzien erhoben hat.

- ^ Boktryckareföreningen, Svenska (1905). "Berthold advertisement". Almänna Svenska Boktryckareföreningens Meddelanden: 106, 336, 368.

- ^ "Reklameschrift Herold". Fonts in Use. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ^ Shinn, Nick (2003). "The Face of Uniformity" (PDF). Graphic Exchange. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ Reynolds, Dan (12 June 2018). "Distribution of sans serif typefaces across German-speaking foundries in the 19th century". Typeoff. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ a b Reynolds 2019, p. 139. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFReynolds2019 (help)

- ^ "Brass Rules". The Happy Dragon's Press. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ a b c Handbuch der Schriftarten. Leipzig: Seemann. 1926. pp. 181–218. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Kupferschmid, Indra. "Some notes on the history of Akzidenz-Grotesk Part 2". kupferschrift. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ Reynolds 2019, p. 137. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFReynolds2019 (help)

- ^ a b Reynolds, Dan (23 August 2019). "Note on the original design patent for Akzidenz-Grotesk". TypeOff. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ Cees W. de Jong; Alston W. Purvis; Friedrich Friedl (2005). Creative Type: A Sourcebook of Classic and Contemporary Letterforms. Inmerc. p. 331. ISBN 978-90-6611-250-6.

- ^ a b c Kupferschmid, Indra. "Notes on the history of Akzidenz-Grotesk Part 2a – Timeline". Kupferschrift. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ^ Wanetzky, Harald (1995). Typotektur: Architektur und Typografie im 20. Jahrhundert : der Modellfall einer Zusammenführung.

Berthold und Bauer werben im Jahre 1899 mit einem aus heutiger Sicht seltsam anmutenden Jugendstillayout für die 'Accidenz-Grotesk'.

- ^ Reynolds, Dan. "Also, the name Accidenz-Grotesk likely came from Bauer & Co., too. That foundry's founder F.W. Bauer had earlier cut a typeface called Accidenz-Gothisch". Twitter. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d Spiekermann, Erik. "Akzidenz-Grotesk (Re-)Release Dates (comments on Typophile thread)". Typophile (archived). Archived from the original on 2014-06-28. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ "Schriftprobe". Archiv für Buchgewerbe. 40: 19. 1903. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

Eine neue recht verwendbare Schrift hat die Firma H. Berthold Akt.-Ges in Berlin geschaffen, eine in acht Graden geschnittene Royal-Grotesk, die sich zu allen besseren Accidenzen verwenden lassen und infolge ihres scharfen und sauberen Schnitts zur besten Wirkung gelangen wird. Auf eine kleine, vielleicht unbeabsichtigte Unschönheit möchten wir doch hinweisen. Diese betrifft das Versal-R, dessen Querstrich zu tief steht, was auffällt und störend wirkt, wenn der Buchstabe zwischen B und E steht. Vielleicht ist hier eine Verbesserung noch angängig. Chronos.

- ^ Reynolds, Dan (13 April 2019). "Research update: Distribution of sans serifs in German-speaking foundries during the nineteenth century". Typeoff. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ^ Reynolds, Dan (29 April 2019). "Longina-Schriften". Flickr. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ Hardwig, Florian; Reynolds, Dan (14 June 2019). "Mallet Magic – Harry Breuer And His Quintet". Fonts in Use. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- ^ Schwemer-Scheddin 2003, p. 24:"Royal-Grotesk was my favourite font from the beginning. I used it on my first Berthold business card and my letterhead. It's a delicate, slender piece of engraving and came from the royal punchcutter Ferdinand Theinhardt. His foundry came to Berthold in 1908. People always talk about how this sans-serif typeface is "anonymous", but it's now clear that it's Theinhardt's. Royal-Grotesk was made for royal scientific printing. And Theinhardt added to it the normal, semi-bold and bold. For me those four weights of Akzidenz-Grotesk are the best."

- ^ Liste der Hieroglyphischen Typen aus der Schriftgießerei des Herrn F. Theinhardt in Berlin. Buchdruckerei der Königl. Akademie der Wissenschaften (G. Vogt). 1875. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ^ Reynolds, Dan (22 February 2019). "The Academy of Sciences of the USSR's hieroglyphs font (1928)". Typeoff. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ a b Reynolds, Dan (25 February 2019). "Berlin locations of the old Ferd. Theinhardt foundry". Typeoff. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ Kupferschmid, Indra. "Some notes on the history of Akzidenz-Grotesk". kupferschrift*. Archived from the original on 30 March 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2017.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- ^ Spiekermann, Erik; Reynolds, Dan. "Akzidenz Grotesk roots (comments on forum thread)". Typophile (archived). Archived from the original on 2015-03-21. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ Jan-Pool, Albert (23 January 2014). "Stefan George Schrift". Flickr. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^ "Ferdinand Theinhardt" (PDF). Klingspor Museum. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^ Reynolds, Dan. "Origin of Akzidenz-Grotesk's weight now sorted. @kupfers was right. Berthold derived it from an earlier Bauer & Co. display typeface". Twitter. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

Origin of Akzidenz-Grotesk's weight now sorted. @kupfers was right. Berthold derived it from an earlier Bauer & Co. display typeface called Schattierte Grotesk. Berthold bought Bauer & Co. The new Berlin + Stuttgart company made an "unschattierte" version, which Berthold began selling in 1898 as Accidenz-Grotesk.

- ^ Reynolds 2019, p. 138. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFReynolds2019 (help)

- ^ Paul Shaw (April 2017). Revival Type: Digital Typefaces Inspired by the Past. Yale University Press. pp. 190–205. ISBN 978-0-300-21929-6.

- ^ "Venus – MyFonts". MyFonts. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ a b Shaw, Paul; Kupferschmid, Indra. "Blue Pencil no. 18—Arial addendum no. 3". Paul Shaw Letter Design (blog). Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ^ a b Tracy 2003, p. 98.

- ^ Tracy 2003, p. 58, 92.

- ^ N1KE (21 February 2012). "Type Specimen book H. Berthold AG, ca 1913". Flickr. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ Cartwright, Justin (14 January 2006). "Prophet of doom". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- ^ Burke, Christopher (December 1998). Paul Renner: The Art of Typography. Princeton Architectural Press. pp. 115–8. ISBN 978-1-56898-158-1.

- ^ Achim Aurnhammer; Wolfgang Braungart; Stefan Breuer; Ute Oelmann (1 January 2016). Stefan George und sein Kreis: Ein Handbuch. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. pp. 480–481. ISBN 978-3-11-045688-2.

- ^ Gewerblicher Rechtsschutz und Urheberrecht Zeitschrift. 1943. p. 45.

Gedruckt wurde seit 1904 in der sogenannten Stefan-George-Schrift, einer Letternschrift, die der Graphiker Melchior Lechter im Jahre 1903 in Anlehnung an die Handschrift Georges aus einer freien Akzidenz-Grotesk-Schrift der Schriftgießerei Berthold, Berlin, geschaffen hatte. Stefan George ist 1933, Melchior Lechtor 1938 gestorben.

- ^ Lane, John A.; Lommen, Mathieu; de Zoete, Johan (1998). Dutch Typefounders' Specimens. De Graaf. pp. 29–31. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ^ Middendorp, Jan (2004). Dutch Type. 010 Publishers. p. 45. ISBN 978-90-6450-460-0.

- ^ Day, Kenneth (1956). The Typography of Press Advertisement. pp. 86–8, etc.

- ^ Tracy 2003, p. 96.

- ^ Kupferschmid, Indra. "Live Type Research in Barcelona". Kupferschrift. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- ^ Tschichold, Jan (1998). McLean, Ruari; Kinross, Robin (eds.). The New Typography: a handbook for modern designers. University of California Press. ISBN 0520071476.

- ^ a b c d Eskilson, Stephen (28 February 2012). Graphic Design: A New History, Second Edition. Yale University Press. pp. 290–1. ISBN 978-0-300-17260-7.

- ^ Schwemer-Scheddin, Yvonne. "Reputations: Josef Müller-Brockmann". Eye. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- ^ Raposo, Tânia (15 July 2013). "Campaign posters for the Swiss Automobile Club". Fonts In Use. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ Coles, Stephen (3 April 2012). "Posters for the Zurich Town Hall". Fonts In Use. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d Berthold exklusiv Probe 013: Akzidenz-Grotesk. Berlin: Berthold Fototype. 1984. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ a b c Müller, Lars; Malsy, Victor; Kupferschmid, Indra (2009). Helvetica Forever: Story of a Typeface. Lars Müller. ISBN 978-3037781210.

- ^ Stiehl, Ulrich. "Akzidenz-Grotesk auf der Linotype-Zeilengußmaschine (German)" (PDF). Sanskritweb (blog). Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Akzidenz-Grotesk für Hand- und Maschinensatz (advert)". Gebrauchsgrafik. Berthold/Linotype (advert): 56. 1959.

Die Akzidenz-Grotesk is sechzig Jahre alt, und doch scheint sie nicht zu veraltern, sondern in ihrer Frische und Lebendigkeit für immer zu verharren. Sie erfreut sich solcher Beliebheit, daß sie nun auf die Setzmaschine kam. Zusammen mit den Handsatz-Garnituren bilden die Linotype-Werkschiftgrade eine sehr stattliche Familie, die der Gestalter und Drucker oft und gern bei seiner Arbeit in Anspruch nehmen wird.

- ^ a b c d Kupferschmid, Indra. "The Birth of a Giant". Font Bureau. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ^ Hollis 2006, p. 201.

- ^ Grace Lees-Maffei (8 January 2015). Iconic Designs: 50 Stories about 50 Things. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 81–3. ISBN 978-0-85785-353-0.

- ^ Lucienne Roberts (1 November 2005). Drip-dry Shirts: The Evolution of the Graphic Designer. AVA Publishing. pp. 27–29. ISBN 978-2-940373-08-6.

- ^ Shaw, Paul. "The (Mostly) True Story of Helvetica and the New York City Subway". AIGA. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

Exactly when Amsterdam Continental began importing Standard is unclear but it appears on several record album covers as early as 1957.

- ^ Devroye, Luc. "Amsterdam Continental: A Handbook of Types" (PDF). Type Design Information. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ^ Budrick, Callie. "Vintage Fonts: 35 Adverts From the Past". Print. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ^ Shaw, Paul. "From the Archives no. 15—Helvetica and Standard". Paul Shaw Letter Design (blog). Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Schriftprobe Nr. 473. Berlin/Stuttgart: H. Berthold/Zweigwerk Stuttgart. c. 1966.

- ^ Akzidenz-Grotesk von Berthold, Probe 429A (digitisation: Stephen Coles/Thomas Maier). Stuttgart: H. Berthold. c. 1960. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ^ Hermann, Ralf. "Phototypesetting with the Berthold 'diatype'". YouTube. Typography.Guru. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ^ a b c "Akzidenz-Grotesk". Berthold Types blog. Berthold Types. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ^ a b de Jong, Cees W. (2006). Sans Serif: The Ultimate Sourcebook of Classic and Contemporary Sans Serif Typography. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 23. ISBN 9780500513118.

- ^ Reynolds 2019, p. 141. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFReynolds2019 (help)

- ^ Gerstner 1963, p. 8.

- ^ "Gerstner-Programm". Fonts in Use. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ a b Schwemer-Scheddin 2003, p. 26.

- ^ Raabe, Marcel. "Gerstner-Programm". Forgotten Shapes. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- ^ "Berthold Goes Bankrupt". Telecompaper. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ Hunt, Harvey (2004). "Erik Spiekermann's Statements re Berthold". Typophile (archived). Berthold Types. Archived from the original on 2014-10-23. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ Berthold Announces the Release of Akzidenz-Grotesk in OpenType Format Archived 2006-05-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "News: AG goes Greek and Cyrillic". Microsoft Typography (archived). Microsoft. Archived from the original on 2017-06-19. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ Hollis, Richard. "The designer as programmer". Eye. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ Lippa, Domenic (14 September 2013). "The 10 best fonts". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ a b c Sowersby, Kris. "Söhne design information". Klim Type Foundry. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ Schwemer-Scheddin 2003, p. 24

- ^ Frutiger 2009, p. 96.

- ^ a b c Reynolds, Dan (2 November 2010). "Review: Graphic Design and the Soul". TypeOff. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

The capital letters are slightly too dark, and slightly too close to the lowercase letters that follow them in a word.

- ^ Homola 2004, p. 33.

- ^ Frutiger 2009, p. 250.

- ^ Gerstner 1963, p. 3.

- ^ a b c "Differences - Akzidenz-Grotesk and Futura". Identifont. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ "Differences - Akzidenz-Grotesk and Franklin Gothic". Identifont. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ Frutiger 2009, p. 18.

- ^ Frutiger 2009, p. 61.

- ^ a b "Differences - Akzidenz-Grotesk and Helvetica". Identifont. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ Majoor, Martin. "Inclined to be dull". Eye magazine. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ a b Reynolds, Dan (12 February 2019). "German, Swiss, and Austrian typefaces named Royal or Akzidenz". TypeOff. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ Peter Karow (6 December 2012). Font Technology: Methods and Tools. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 225–8, 235–40. ISBN 978-3-642-78505-4.

- ^ Schwartz, Christian. "Neue Haas Grotesk". Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ Spiekermann, Eric. "Twitter post". Twitter. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

AG Buch war GGL's Antwort auf Helvetica, für die Berthold keine Lizenz kriegte von Linotype.

- ^ Schwemer-Scheddin 2003, p. 23.

- ^ "AG Book Pro". Berthold. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "AG Book Rounded Pro". Berthold. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "AG Schoolbook® Pro". Berthold Types. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ Walker, Sue; Reynolds, Linda (1 January 2003). "Serifs, sans serifs and infant characters in children's reading books". Information Design Journal. 11 (3): 106–122. doi:10.1075/idj.11.2.04wal.

- ^ a b "Differences - AG Schoolbook Medium and AG Book". Identifont. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ Coles, Stephen (26 August 2012). "Wikipedia Redefined". Fonts in Use. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ a b Coles, Stephen (20 March 2016). "Design Museum". Fonts in Use. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ a b "AG Old Face Pro". Berthold Types. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ a b c "News: The Next Akzidenz". Microsoft Typography (archived). Microsoft. Archived from the original on 2017-06-19. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ Gehlhaar, Jens. "Neuwelt: an optimistic transatlantic sans serif type family". Jens Gehlhaar. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Frutiger 2009, p. 97: "The curved indent in the upstroke of the 1, like in Akzidenz Grotesk, was something alien to me. An upstroke is something simple and not so fanciful, horizontal with a bump in it. Accordingly, my 1 is simple, like the 7 is too."

- ^ a b Calvert, Margaret. "New Transport". A2-Type. Retrieved 1 March 2016.

- ^ Sudjic, Deyan. "From Akzidenz to Transport Solution". Port. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ Jackson, Tanya (31 January 2013). British Railways: The Nation's Railway. History Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-7524-9742-6.

- ^ Kupferschmid, Indra (30 August 2007). "Haas Normal-Grotesk". Flickr. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ^ Kupferschmid, Indra. "Wagner & Schmidt, etc". kupferschrift. Archived from the original on 19 January 2017. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ^ "BERTHOLD AKZIDENZ-GROTESK - Trademark Details". Justia. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ "AKZIDENZ-GROTESK NEXT – Trademark Details". Justia. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ^ "Compendium of U.S. Copyright Office Practices, § 906.4 ("Typeface, Typefont, Lettering, Calligraphy, and Typographic Ornamentation")" (PDF). United States Copyright Office. December 22, 2014. p. 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 December 2014. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

The copyright law does not protect typeface or mere variations of typographic ornamentation or lettering.

- ^ Justus, Dana; Estoesa, Ivy Clarice. ""Types" of Protection for Font and Typeface Designs". The National Law Review. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ Coles, Stephen. "The Last Time the US Considered Copyright Protection for Typefaces". Typographica. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ "Theinhardt". Optimo. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ Spiekermann, Erik. "Twitter post". Twitter. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

ist ja auch die beste AG

- ^ "Basic Commercial LT". MyFonts. Linotype. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ "Gothic 725". MyFonts. Bitstream Inc. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ Castle, Jason. "Standard CT". MyFonts. CastleType. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ^ Stinson, Liz (21 January 2020). "A Modern Sans-serif Infused With the Spirit of the NYC Subway". AIGA Eye On Design. AIGA. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ^ Blažek, Filip. "Söhne". Typographica. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ "NYC Sans". Hex Projects. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ^ "NYC SANS – Trademark Details". Justia. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ^ Miller, Meg (10 June 2016). "NYC Gets A Major Rebrand (And Its First Official Pictograms)". Fast Company. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ^ Lessard, Emily. "NYC Go rebrand details". Emily Lessard. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ^ "Transport". MyFonts. URW++. Retrieved 1 March 2016.

- ^ "FF Real". Linotype. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ Ulrich, Ferdinand. "Interview with Erik Spiekermann and Ralph du Carrois". FontShop. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ "St G Schrift". P22. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ "Elements of the brand". Arizona State University. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ "Brand identity at a glance" (PDF). American Red Cross. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ "Displaying the Air Force Symbol". United States Air Force. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ "Chicago Font Co. Takes Aim at Target's Use Of Typeface – Law360". www.law360.com. Retrieved 2017-10-06.

Sources[]

- Frutiger, Adrian (2009). Osterer, Heiden; Stamm, Philipp (eds.). Typefaces: The Complete Works (English ed.). Basel: Birkhäuser. ISBN 978-3764385811.

- Gerstner, Karl (1963). "Die alte Akzidenz-Grotesk auf neuer Basis" (PDF). Der Druckspiegel. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-10-15. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- Hollis, Richard (2006). Swiss Graphic Design: The Origins and Growth of an International Style, 1920–1965. Laurence King Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85669-487-2.

- Homola, Wolfgang (2004). Type design in the age of the machine. The 'Breite Grotesk' by J. G. Schelter & Giesecke (PDF). University of Reading (archived). Archived from the original on 12 January 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2018.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- Müller, Lars; Malsy, Victor; Kupferschmid, Indra (2009). Helvetica Forever: Story of a Typeface. Lars Müller. ISBN 978-3037781210.

- Reynolds, Dan (2019). "The godfather: retracing the origins of Akzidenz-Grotesk". Footnotes (3).

- Reynolds, Dan (2020). "Chapter 1". Schriftkünstler – A historiographic examination of the relationship between handcraft and art regarding the design and making of printers' type in Germany between 1871 and 1914. Hochschule für Bildende Künste Braunschweig (PhD thesis). Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- Reynolds, Dan (2020). "Chapter 2: Research methods". Schriftkünstler – A historiographic examination of the relationship between handcraft and art regarding the design and making of printers' type in Germany between 1871 and 1914. Hochschule für Bildende Künste Braunschweig (PhD thesis). Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- Reynolds, Dan (2020). "Chapter 3: Writing history as a designer". Schriftkünstler – A historiographic examination of the relationship between handcraft and art regarding the design and making of printers' type in Germany between 1871 and 1914. Hochschule für Bildende Künste Braunschweig (PhD thesis). Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- Reynolds, Dan (2020). "Chapter 6: Type design in German foundries from 1871 to 1914". Schriftkünstler – A historiographic examination of the relationship between handcraft and art regarding the design and making of printers' type in Germany between 1871 and 1914. Hochschule für Bildende Künste Braunschweig (PhD thesis). Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- Schwemer-Scheddin, Yvonne (2003). "Sonderheft Günter Gerhard Lange". Typografische Monatsblätter.

- Tracy, Walter (2003). Letters of Credit: A View of Type Design. D.R. Godine. ISBN 978-1-56792-240-0.

External links[]

- Berthold pages: Akzidenz-Grotesk Pro+, Akzidenz-Grotesk Next, AG Old Face, AG Book Pro+, AG Book Rounded, AG Book Stencil et al, AG Schoolbook,

- Akzidenz Grotesk sample books digitised by Ulrich Stiehl

- Berthold specimens from c. 1913, showing Schattierte-Grotesk and co-branding mentioning Berthold and Bauer

- Fonts in Use coverage: Akzidenz-Grotesk, AG Condensed, AG Book, Standard (for American uses)

- Probe 429A (c. 1960 specimen, photographed by Stephen Coles/Thomas Maier)

- Berthold advertisement from 1937 not showing Akzidenz-Grotesk. The advert showcases "modern and successful" faces, illustrating the eclipse of Akzidenz-Grotesk in this period.

- Berthold typefaces

- Linotype typefaces

- Grotesque sans-serif typefaces

- Letterpress typefaces

- Photocomposition typefaces

- Digital typefaces

- Typefaces with infant variants

- Products introduced in 1898