Oblique type

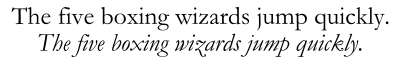

Oblique type is a form of type that slants slightly to the right, used for the same purposes as italic type. Unlike italic type, however, it does not use different glyph shapes; it uses the same glyphs as roman type, except slanted. Oblique and italic type are technical terms to distinguish between the two ways of creating slanted font styles; oblique designs may be labelled italic by companies selling fonts or by computer programs. Oblique designs may also be called slanted or sloped roman styles.[1] Oblique fonts, as supplied by a font designer, may be simply slanted, but this is often not the case: many have slight corrections made to them to give curves more consistent widths, so they retain the proportions of counters and the thick-and-thin quality of strokes from the regular design.[2][3]

Type designers have described oblique type as less organic and calligraphic than italics, which in some situations may be preferred. Contemporary type designer Jeremy Tankard stated that he had avoided a true italic 'a' and 'e' in his design Bliss due to finding them "too soft", while Hoefler and Frere-Jones have described obliques as more "keen and insistent".[4][5]

Obliques and italics[]

Italic designs are not just the slanted version of the regular (roman) style; they are influenced by handwriting, with a single-storey a and an f that descends below the line of text. Some may even link up, like cursive (joined-up) handwriting. Obliques by contrast are "simply" sloped. In addition, italic styles are often quite noticeably narrower than roman type, while oblique styles are not.

Specific typefaces[]

Few typefaces have both oblique and italic designs, as this is generally a fundamental design choice about how the font should look. A font designer normally decides to design their font with one or the other.

Serif fonts[]

Historically, it was normal for all Latin-alphabet serif fonts to have true italics, but in the late nineteenth century some "sloped romans" were created by European and American foundries, particularly for display type and headings. Notable typefaces in this style include Bookman Old Style in metal type (although not many recent versions), Linn Boyd Benton's "self-spacing" type and the Central Type Foundry's "De Vinne" wedge-serif display face.[6] European examples included Genzsch Antiqua from Genzsch & Heyse.[7][8]

Almost all modern serif fonts have true italic designs. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a number of type foundries such as American Type Founders and Genzsch & Heyse offered serif typefaces with oblique rather than italic designs, especially display typefaces, but these designs (such as Genzsch Antiqua) have mostly disappeared.[9][10][11] An exception is American Type Founders' Bookman, offered in some releases with the oblique of its metal type version.[12] An unusual example of an oblique font from the inter-war period is the display face Koch Antiqua. With a partly oblique lower case, it also makes the italic capitals inline in the style of blackletter capitals in the larger sizes of the metal type. It was developed by Rudolph Koch, a type designer who had previously specialised in to blackletter font design (which does not use italics); Walter Tracy described his design as "uninhibited by the traditions of roman and italic".[13]

The printing historian and artistic director Stanley Morison was for a time in the inter-war period interested in the oblique type style, which he felt stood out in text less than a true italic and should supersede it. He argued in his article Towards an Ideal Italic that serif book typefaces should have as the default sloped form an oblique and as a complement a script typeface where a more decorative form was preferred.[14] He made an attempt to promote the idea by commissioning the typeface Perpetua from Eric Gill with a sloped roman rather than an italic, but came to find the style unattractive; Perpetua's italic when finally issued had the conventional italic 'a', 'e' and 'f'.[15][16] Morison wrote to his friend, type designer Jan van Krimpen, that in developing Perpetua's italic "we did not give enough slope to it. When we added more slope, it seemed that the font required a little more cursive to it."[9][a] A few other type designers replicated his approach for a time: van Krimpen's Romulus and William Addison Dwiggins' Electra were both released with obliques.[b] Morison's Times New Roman typeface has a very traditional true italic in the style of the late eighteenth century, which he later wryly commented owed "more to Didot than dogma".[19]

Sans-serif fonts[]

Many sans-serif typefaces use plainer oblique designs instead of italic ones. This is especially true with grotesque designs like Helvetica, which have a spare, industrial aesthetic, and geometric ones like Futura. (As many sans-serif fonts were intended for use on headings and posters, especially early ones, some were not designed with italics at all because these were considered unnecessary.)

Humanist sans-serif typefaces, however, often use true italic styles since they are more influenced by calligraphy and traditional serif fonts. Notable humanist sans-serif typefaces include Gill Sans, Goudy Sans, FF Meta and FF Scala Sans; all have italic designs.[21] Adrian Frutiger and other prominent designers have defended obliques as more appropriate for the aesthetic of sans-serif fonts, while Martin Majoor has supported the use of true italics.[22][23]

Automated obliques, or "fake italics"[]

Some computer programs handling text may simply generate an oblique form, a "fake italic", by slanting the normal font when they find no italic or oblique style installed.[24] It may not be clear to the user where the oblique form comes from (whether it is a correctly installed oblique font or an automatically slanted design, which may look worse) unless they check their installed fonts. Slanting the regular style to create an oblique was particularly often done on early computer and phototypesetting systems in the 1970s and -80s to save time and memory space, especially in lower-quality printing of ephemera and newspapers.[9]

See also[]

- Technical lettering § Lettering B

References[]

- ^ Tracy, Walter. Letters of Credit. pp. 61–5.

- ^ Simonson, Mark. "Fake vs. True Italics". Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ^ Simonson, Mark. "Ain't What ITC Used To Be". Typographica. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ^ Tankard, Jeremy. "Bliss". Jeremy Tankard Typography. Archived from the original on 17 July 2014. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ Frere-Jones, Tobias; Hoefler, Jonathan. "Whitney". Hoefler & Frere-Jones. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ Simonson, Mark. "Bookmania". Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ^ "Typophile discussion". Typophile. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- ^ Devroye, Luc. "Friedrich Bauer". Type Design Information. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- ^ a b c Walter Tracy (January 2003). Letters of Credit: A View of Type Design. D.R. Godine. pp. 61–4. ISBN 978-1-56792-240-0.

- ^ "Typophile discussion". Typophile. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- ^ Devroye, Luc. "Friedrich Bauer". Type Design Information. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- ^ Simonson, Mark. "Bookmania". Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ^ Tracy, Walter. Letters of Credit. pp. 162–3.

- ^ Morison, Stanley. Towards an Ideal Italic.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 10 January 2012. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Monotype Imaging: Perpetua - ^ Lo Celso, Alejandro. "Serial Type Families" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 November 2014.

- ^ "Recasting Electra as Aluminia". Letterform Archive. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ^ Puckett, James. "Draughtsman's Alphabets published by Keuffel & Esser". dailytypespecimen. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ^ Morison, Stanley. "Changing the Times". Eye. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ Specimens of type, borders, ornaments, brass rules and cuts, etc. : catalogue of printing machinery and materials, wood goods, etc. American Type Founders Company. 1897. p. 340. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ^ "Goudy Sans". Linotype.com. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- ^ Frutiger, Adrian (8 May 2014). Typefaces: The Complete Works (2 ed.). Walter de Gruyter. p. 260. ISBN 978-3038212607.

- ^ Majoor, Martin. "My Type-Design Philosophy". Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ^ "Fonts". W3.org. Archived from the original on 14 May 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

Notes[]

- ^ Spelling modernised to avoid confusion–Morison wrote 'fount', the usual spelling in British English at the time.

- ^ Electra was later reissued–although not in Britain–with a true italic, which is the only form most digitisations include. An exception is Jim Parkinson's Aluminia revival, which includes both.[17] Romulus was issued on Morison's plan with an oblique a script typeface companion, Cancelleresca Bastarda, which has longer ascenders and descenders than Romulus does. Digital period type designer James Puckett describes the obliques on both Romulus and Electra as "spectacular failures [which] pretty much killed the idea for serifed types."[18]

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Oblique fonts. |

- Typographica: Ain't What ITC Used to Be

- Compare "Univers 65 Bold Oblique" and "Univers 66 Bold Italic"

- CSS font-style: oblique vs italic"

- Typography