Ligature (writing)

In writing and typography, a ligature occurs where two or more graphemes or letters are joined to form a single glyph. Examples are the characters æ and œ used in English and French, in which the letters 'a' and 'e' are joined for the first ligature and the letters 'o' and 'e' are joined for the second ligature. For stylistic and legibility reasons, 'f' and 'i' are often merged to create 'fi' (where the tittle on the 'i' merges with the hood of the 'f'); the same is true of 's' and 't' to create 'st'. The common ampersand (&) developed from a ligature in which the handwritten Latin letters 'e' and 't' (spelling et, Latin for 'and') were combined.[1]

History[]

The earliest known script Sumerian cuneiform and Egyptian hieratic both include many cases of character combinations that gradually evolve from ligatures into separately recognizable characters. Other notable ligatures, such as the Brahmic abugidas and the Germanic bind rune, figure prominently throughout ancient manuscripts. These new glyphs emerge alongside the proliferation of writing with a stylus, whether on paper or clay, and often for a practical reason: faster handwriting. Merchants especially needed a way to speed up the process of written communication and found that conjoining letters and abbreviating words for lay use was more convenient for record keeping and transaction than the bulky long forms.

Around the 9th and 10th centuries, monasteries became a fountainhead for these type of script modifications. Medieval scribes who wrote in Latin increased their writing speed by combining characters and by introducing notational abbreviations. Others conjoined letters for aesthetic purposes. For example, in blackletter, letters with right-facing bowls (b, o, and p) and those with left-facing bowls (c, e, o, d, g and q) were written with the facing edges of the bowls superimposed. In many script forms, characters such as h, m, and n had their vertical strokes superimposed. Scribes also used notational abbreviations to avoid having to write a whole character in one stroke. Manuscripts in the fourteenth century employed hundreds of such abbreviations.

In hand writing, a ligature is made by joining two or more characters in an atypical fashion by merging their parts, or by writing one above or inside the other. In printing, a ligature is a group of characters that is typeset as a unit, so the characters do not have to be joined. For example, in some cases the fi ligature prints the letters f and i with a greater separation than when they are typeset as separate letters. When printing with movable type was invented around 1450,[4] typefaces included many ligatures and additional letters, as they were based on handwriting. Ligatures made printing with movable type easier because one block would replace frequent combinations of letters and also allowed more complex and interesting character designs which would otherwise collide with one another.

Ligatures began to fall out of use because of their complexity in the 20th century. Sans serif typefaces, increasingly used for body text, generally avoid ligatures, though notable exceptions include Gill Sans and Futura. Inexpensive phototypesetting machines in the 1970s (which did not require journeyman knowledge or training to operate) also generally avoid them. A few, however, became characters in their own right, see below the sections about German ß, various Latin accented letters, & et al..

The trend against digraph use was further strengthened by the desktop publishing revolution starting around 1977 with the production of the Apple II. Early computer software in particular had no way to allow for ligature substitution (the automatic use of ligatures where appropriate), while most new digital typefaces did not include ligatures. As most of the early PC development was designed for the English language (which already treated ligatures as optional at best) dependence on ligatures did not carry over to digital. Ligature use fell as the number of traditional hand compositors and hot metal typesetting machine operators dropped because of the mass production of the IBM Selectric brand of electric typewriter in 1961. A designer active in the period commented: "some of the world's greatest typefaces were quickly becoming some of the world's worst fonts."[5]

Ligatures have grown in popularity in the 21st century because of an increasing interest in creating typesetting systems that evoke arcane designs and classical scripts. One of the first computer typesetting programs to take advantage of computer-driven typesetting (and later laser printers) was Donald Knuth's TeX program. Now the standard method of mathematical typesetting, its default fonts are explicitly based on nineteenth-century styles. Many new fonts feature extensive ligature sets; these include FF Scala, Seria and others by Martin Majoor and Hoefler Text by Jonathan Hoefler. Mrs Eaves by Zuzana Licko contains a particularly large set to allow designers to create dramatic display text with a feel of antiquity. A parallel use of ligatures is seen in the creation of script fonts that join letterforms to simulate handwriting effectively. This trend is caused in part by the increased support for other languages and alphabets in modern computing, many of which use ligatures somewhat extensively. This has caused the development of new digital typesetting techniques such as OpenType, and the incorporation of ligature support into the text display systems of macOS, Windows, and applications like Microsoft Office. An increasing modern trend is to use a "Th" ligature which reduces spacing between these letters to make it easier to read, a trait infrequent in metal type.[6][7][8]

Today, modern font programming divides ligatures into three groups, which can be activated separately: standard, contextual and historical. Standard ligatures are needed to allow the font to display without errors such as character collision. Designers sometimes find contextual and historic ligatures desirable for creating effects or to evoke an old-fashioned print look.

Latin alphabet[]

Stylistic ligatures[]

Many ligatures combine f with the following letter. A particularly prominent example is fi (or fi, rendered with two normal letters). The tittle of the i in many typefaces collides with the hood of the f when placed beside each other in a word, and are combined into a single glyph with the tittle absorbed into the f. Other ligatures with the letter f include fj,[note 1] fl (fl), ff (ff), ffi (ffi), and ffl (ffl). Ligatures for fa, fe, fo, fr, fs, ft, fb, fh, fu, fy, and for f followed by a full stop, comma, or hyphen are also used, as well as the equivalent set for the doubled ff.

These arose because with the usual type sort for lowercase f, the end of its hood is on a kern, which would be damaged by collision with raised parts of the next letter.

Ligatures crossing the morpheme boundary of a composite word are sometimes considered incorrect, especially in official German orthography as outlined in the Duden. An English example of this would be ff in shelfful; a German example would be Schifffahrt ("boat trip").[note 2] Some computer programs (such as TeX) provide a setting to disable ligatures for German, while some users have also written macros to identify which ligatures to disable.[9][10]

Turkish distinguishes dotted and dotless "I". In a ligature with f (in words such as fırın and fikir), this contrast would be obscured. The fi ligature is therefore not used in Turkish typography, and neither are other ligatures like that for fl, which would be rare anyway.

Remnants of the ligatures ſʒ/ſz ("sharp s", eszett) and tʒ/tz ("sharp t", tezett) from Fraktur, a family of German blackletter typefaces, originally mandatory in Fraktur but now employed only stylistically, can be seen to this day on street signs for city squares whose name contains Platz or ends in -platz. Instead, the "sz" ligature has merged into a single character, the German ß – see below.

Sometimes, ligatures for st (st), ſt (ſt), ch, ck, ct, Qu and Th are used (e.g. in the typeface Linux Libertine).

Besides conventional ligatures, in the metal type era some newspapers commissioned custom condensed single sorts for the names of common long names that might appear in news headings, such as "Eisenhower", "Chamberlain", and others. In these cases the characters did not appear combined, just more tightly spaced than if printed conventionally.[11]

German ß[]

The German Eszett (also called the scharfes S, meaning sharp s) ß is an official letter of the alphabet in Germany and Austria. There is no general consensus about its history. Its name Es-zett (meaning S-Z) suggests a connection of "long s and z" (ſʒ) but the Latin script also knows a ligature of "long s over round s" (ſs). The latter is used as the design principle for the character in most of today's typefaces. Since German was mostly set in blackletter typefaces until the 1940s, and those typefaces were rarely set in uppercase, a capital version of the Eszett never came into common use, even though its creation has been discussed since the end of the 19th century. Therefore, the common replacement in uppercase typesetting was originally SZ (Maße "measure" → MASZE, different from Masse "mass" → MASSE) and later SS (Maße → MASSE). The SS replacement was until 2017 the only valid spelling according to the official orthography (the so-called Rechtschreibreform) in Germany and Austria. For German writing in Switzerland, the ß is omitted altogether in favour of ss, hence the German jest about the Swiss: "Wie trinken die Schweizer Bier? – In Massen." ("How do the Swiss drink beer? – In mass" instead of two other meanings if it had been written as "in Maßen": one is "not too much" or "in moderation", the other to drink out of jugs that hold exactly one Maß of volume). The capital version (ẞ) of the Eszett character has been part of Unicode since 2008, and has appeared in more and more typefaces. The new character entered mainstream writing in June 2017. A new standardized German keyboard layout (DIN 2137-T2) has included the capital ß since 2012. Since the end of 2010, the Ständiger Ausschuss für geographische Namen (StAGN) has suggested the new upper case character for "ß" rather than replacing it with "SS" or "SZ" for geographical names.[12]

Massachusett ꝏ[]

A prominent feature of the colonial orthography created by John Eliot (later used in the first Bible printed in the Americas, the Massachusett-language Mamusse Wunneetupanatamwe Up-Biblum God, published in 1663) was the use of the double-o ligature "ꝏ" to represent the "oo" (/u/) of "food" as opposed to the "oo" (/ʊ/) of "hook" (although Eliot himself used "oo" and "ꝏ" interchangeably). In the orthography in use since 2000 in the Wampanoag communities participating in the Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project, the ligature was replaced with the numeral 8, partly because of its ease in typesetting and display as well as its similarity to the o-u ligature Ȣ used in Abenaki. For example, compare the colonial-era spelling seepꝏash[13] with the modern WLRP spelling seep8ash.[14]

Letter W[]

As the letter W is an addition to the Latin alphabet that originated in the seventh century, the phoneme it represents was formerly written in various ways. In Old English, the runic letter wynn (Ƿ) was used, but Norman influence forced wynn out of use. By the 14th century, the "new" letter W, originated as two Vs or Us joined together, developed into a legitimate letter with its own position in the alphabet. Because of its relative youth compared to other letters of the alphabet, only a few European languages (English, Dutch, German, Polish, Welsh, Maltese, and Walloon) use the letter in native words.

Æ and Œ[]

The character Æ (lower case æ; in ancient times named æsc) when used in the Danish, Norwegian, or Icelandic languages, as well as in the related Old English language, is not a typographic ligature. It is a distinct letter—a vowel—and when alphabetised, is given a different place in the alphabetic order.

In modern English orthography, Æ is not considered an independent letter but a spelling variant, for example: "encyclopædia" versus "encyclopaedia" or "encyclopedia". In this use, Æ comes from Medieval Latin, where it was an optional ligature in some specific words that had been transliterated and borrowed from Ancient Greek, for example, "Æneas". It is still found as a variant in English and French words descended or borrowed from Medieval Latin, but the trend has recently been towards printing the A and E separately.[15] This means that, although both Old English and Modern English have made use of the character, the purposes were different.

Similarly, Œ and œ, while normally printed as ligatures in French, are replaced by component letters if technical restrictions require it.

Umlaut[]

In German orthography, the umlauted vowels ä, ö, and ü historically arose from ae, oe, ue ligatures (strictly, from superscript e, viz. aͤ, oͤ, uͤ). It is common practice to replace them with ae, oe, ue digraphs when the diacritics are unavailable, for example in electronic conversation. Phone books treat umlauted vowels as equivalent to the relevant digraph (so that a name Müller will appear at the same place as if it were spelled Mueller; German surnames have a strongly fixed orthography, either a name is spelled with ü or with ue); however, the alphabetic order used in other books treats them as equivalent to the simple letters a, o and u. The convention in Scandinavian languages and Finnish is different: there the umlaut vowels are treated as independent letters with positions at the end of the alphabet.

Ring[]

The ring diacritic used in vowels such as å likewise originated as an o-ligature.[16] Before the replacement of the older "aa" with "å" became a de facto practice, an "a" with another "a" on top (aͣ) could sometimes be used, for example in Johannes Bureus's, Runa: ABC-Boken (1611).[17] The uo ligature ů in particular saw use in Early Modern High German, but it merged in later Germanic languages with u (e.g. MHG fuosz, ENHG fuͦß, Modern German Fuß "foot"). It survives in Czech, where it is called kroužek.

Tilde, circumflex and cedilla[]

The tilde diacritic, used in Spanish as part of the letter ñ, representing the palatal nasal consonant, and in Portuguese for nasalization of a vowel, originated in ligatures where n followed the base letter: Espanna → España.[18] Similarly, the circumflex in French spelling stems from the ligature of a silent s.[19] The French, Portuguese, Catalan and old Spanish letter ç represents a c over a z; the diacritic's name cedilla means "little zed".

Hwair[]

The letter hwair (ƕ), used only in transliteration of the Gothic language, resembles a hw ligature. It was introduced by philologists around 1900 to replace the digraph hv formerly used to express the phoneme in question, e.g. by Migne in the 1860s (Patrologia Latina vol. 18).

Byzantine Ȣ[]

The Byzantines had a unique o-u ligature (Ȣ) that, while originally based on the Greek alphabet's ο-υ, carried over into Latin alphabets as well. This ligature is still seen today on icon artwork in Greek Orthodox churches, and sometimes in graffiti or other forms of informal or decorative writing.

Gha[]

Gha (ƣ), a rarely used letter based on Q and G, was misconstrued by the ISO to be an OI ligature because of its appearance, and is thus known (to the ISO and, in turn, Unicode) as "Oi". Historically, it was used in many Latin-based orthographies of Turkic (e.g., Azeribaijani) and other central Asian languages.

International Phonetic Alphabet[]

The International Phonetic Alphabet formerly used ligatures to represent affricate consonants, of which six are encoded in Unicode: ʣ, ʤ, ʥ, ʦ, ʧ and ʨ. One fricative consonant is still represented with a ligature: ɮ, and the extensions to the IPA contain three more: ʩ, ʪ and ʫ.

Initial Teaching Alphabet[]

The Initial Teaching Alphabet, a short-lived alphabet intended for young children, used a number of ligatures to represent long vowels: ꜷ, æ, œ, ᵫ, ꭡ, and ligatures for ee, ou and oi that are not encoded in Unicode. Ligatures for consonants also existed, including ligatures of ʃh, ʈh, wh, ʗh, ng and a reversed t with h (neither the reversed t nor any of the consonant ligatures are in Unicode).

Rare ligatures[]

Rarer ligatures also exist, such as ꜳ; ꜵ; ꜷ; ꜹ; ꜻ (barred av); ꜽ; ꝏ, which is used in medieval Nordic languages for oː (a long close-mid back rounded vowel),[20] as well as in some orthographies of the Massachusett language to represent uː (a long close back rounded vowel); ᵺ; ỻ, which was used in Medieval Welsh to represent ɬ (the voiceless lateral fricative);[20] ꜩ; ᴂ; ᴔ; and ꭣ.

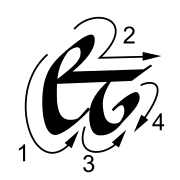

Symbols originating as ligatures[]

The most common ligature is the ampersand &. This was originally a ligature of E and t, forming the Latin word "et", meaning "and". It has exactly the same use in French and in English. The ampersand comes in many different forms. Because of its ubiquity, it is generally no longer considered a ligature, but a logogram. Like many other ligatures, it has at times been considered a letter (e.g., in early Modern English); in English it is pronounced "and", not "et", except in the case of &c, pronounced "et cetera". In most fonts, it does not immediately resemble the two letters used to form it, although certain typefaces use designs in the form of a ligature (examples include the original versions of Futura and Univers, Trebuchet MS, and Civilité, known in modern times as the italic of Garamond).

Similarly, the dollar sign $ possibly originated as a ligature (for "pesos", although there are other theories as well) but is now a logogram.[21] At least once, the United States dollar used a symbol resembling an overlapping U-S ligature, with the right vertical bar of the U intersecting through the middle of the S ( US ) to resemble the modern dollar sign.[22]

The Spanish peseta was sometimes symbolized by a ligature ₧ (from Pts), and the French franc was often symbolized by an F-r ligature (₣).

Alchemy used a set of mostly standardized symbols, many of which were ligatures: