Arctic Council

members observers | |

| Formation | September 19, 1996 (Ottawa Declaration) |

|---|---|

| Type | Intergovernmental organization |

| Purpose | Forum for promoting cooperation, coordination, and interaction among the Arctic states, with the involvement of the Arctic Indigenous communities |

| Headquarters | Tromsø, Norway (since 2012) |

Membership |

|

Main organ | Secretariat |

| Website | arctic-council.org |

| Part of a series on |

| Indigenous rights |

|---|

| Rights |

|

| Governmental organizations |

|

| NGOs and political groups |

|

| Issues |

| Legal representation |

| Category |

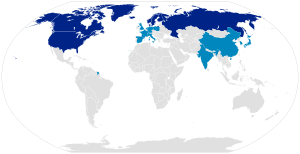

The Arctic Council is a high-level intergovernmental forum that addresses issues faced by the Arctic governments and the indigenous people of the Arctic. The eight countries with sovereignty over the lands within the Arctic Circle constitute the members of the council: Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and the United States. Outside these, there are some observer states.

History[]

The first step towards the formation of the Council occurred in 1991 when the eight Arctic countries signed the Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy (AEPS). The 1996 Ottawa Declaration[1] established the Arctic Council[2] as a forum for promoting cooperation, coordination, and interaction among the Arctic states, with the involvement of the Arctic Indigenous communities and other Arctic inhabitants on issues such as sustainable development and environmental protection.[3][4] The Arctic Council has conducted studies on climate change, oil and gas, and Arctic shipping.[4][5][6][7]

In 2011, the Council member states concluded the Arctic Search and Rescue Agreement, the first binding treaty concluded under the Council's auspices.[4][8]

Membership and participation[]

The Council is made up of member and observer states, Indigenous "permanent participants", and observer organizations.[9]

States[]

Member states[]

Only states with territory in the Arctic can be members of the Council. The member states consist of the following:[10]

- Canada

- Denmark; representing Greenland

- Finland

- Iceland

- Norway

- Russia

- Sweden

- United States

Observer states[]

Observer status is open to non-Arctic states approved by the Council at the Ministerial Meetings that occur once every two years. Observers have no voting rights in the Council. As of May 2019, thirteen non-Arctic states have observer status.[11][12] Observer states receive invitations for most Council meetings. Their participation in projects and task forces within the working groups is not always possible, but this poses few problems as few observer states want to participate at such a detailed level.[4][13]

Observer states consist of the following (2019):[14]

- Germany, 1998

- Netherlands, 1998

- Poland, 1998

- United Kingdom, 1998

- France, 2000

- Spain, 2006

- China, 2013

- India, 2013

- Italy, 2013

- Japan, 2013

- South Korea, 2013

- Singapore, 2013

- Switzerland, 2017

In 2011, the Council clarified its criteria for admission of observers, most notably including a requirement of applicants to "recognize Arctic States' sovereignty, sovereign rights and jurisdiction in the Arctic" and "recognize that an extensive legal framework applies to the Arctic Ocean including, notably, the Law of the Sea, and that this framework provides a solid foundation for responsible management of this ocean".[4]

Pending observer states[]

Pending observer states need to request permission for their presence at each individual meeting; such requests are routine and most of them are granted. At the 2013 Ministerial Meeting in Kiruna, Sweden, the European Union (EU) requested full observer status. It was not granted, mostly because the members do not agree with the EU ban on hunting seals.

Pending observer states are:

- The European Union[15]

- Turkey

The role of observers was re-evaluated, as were the criteria for admission. As a result, the distinction between permanent and ad hoc observers were dropped.[16]

Indigenous Permanent Participants[]

Seven of the eight-member states have sizeable indigenous communities living in their Arctic areas (only Iceland does not have an indigenous community). Organizations of Arctic Indigenous Peoples can obtain the status of Permanent Participant to the Arctic Council,[4] but only if they represent either one indigenous group residing in more than one Arctic State, or two or more Arctic indigenous peoples groups in a single Arctic state. The number of Permanent Participants should at any time be less than the number of members. The category of Permanent Participants has been created to provide for active participation and full consultation with the Arctic indigenous representatives within the Arctic Council. This principle applies to all meetings and activities of the Arctic Council.

Permanent Participants may address the meetings. They may raise points of order that require an immediate decision by the Chairman. Agendas of Ministerial Meetings need to be consulted beforehand with them; they may propose supplementary agenda items. When calling the biannual meetings of Senior Arctic Officials, the Permanent Participants must have been consulted beforehand. Finally, Permanent Participants may propose cooperative activities, such as projects. All this makes the position of Arctic indigenous peoples within the Arctic Council quite unique compared to the (often marginal) role of such peoples in other international governmental fora. However, decision-making in the Arctic Council remains in the hands of the eight-member states, on the basis of consensus.

As of 2014, six Arctic indigenous communities have Permanent Participant status.[4] These groups are represented by

- the Aleut International Association,[17]

- the Arctic Athabaskan Council,[18]

- the Gwich'in Council International,[19]

- the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC),

- the Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON),[20] and

- the Saami Council.[21]

These indigenous organizations vary widely in their organizational capacities and the size of the population they represent. To illustrate, RAIPON represents some 250,000 indigenous people of various (mostly Siberian) peoples; the ICC some 150,000 Inuit. On the other hand, the Gwich'in Council and the Aleut Association each represent only a few thousand people.

However prominent the role of indigenous peoples, the Permanent Participant status does not confer any legal recognition as peoples. The Ottawa Declaration, the Arctic Council's founding document, explicitly states (in a footnote): "The use of the term 'peoples' in this declaration shall not be construed as having any implications as regard the rights which may attach to the term under international law."

The Indigenous Permanent Participants are assisted by the Arctic Council Indigenous Peoples Secretariat.

Observer organizations[]

Approved intergovernmental organizations and Inter-parliamentary institutions (both global and regional), as well as non-governmental organizations can also obtain Observer Status.

Organizations with observer status currently include the Arctic Parliamentarians,[22] International Union for Conservation of Nature, the International Red Cross Federation, the Nordic Council, the Northern Forum,[23] United Nations Development Programme, United Nations Environment Programme; the Association of World Reindeer Herders,[24] Oceana,[25] the University of the Arctic, and the World Wide Fund for Nature-Arctic Programme.

Administrative aspects[]

Meetings[]

The Arctic Council convenes every six months somewhere in the Chair's country for a Senior Arctic Officials (SAO) meeting. SAOs are high-level representatives from the eight-member nations. Sometimes they are ambassadors, but often they are senior foreign ministry officials entrusted with staff-level coordination. Representatives of the six Permanent Participants and the official Observers also are in attendance.

At the end of the two-year cycle, the Chair hosts a Ministerial-level meeting, which is the culmination of the Council's work for that period. Most of the eight-member nations are represented by a Minister from their Foreign Affairs, Northern Affairs, or Environment Ministry.

A formal, though non-binding, "Declaration", named for the town in which the meeting is held, sums up the past accomplishments and the future work of the Council. These Declarations cover climate change, sustainable development, Arctic monitoring and assessment, persistent organic pollutants and other contaminants, and the work of the Council's five Working Groups.

Arctic Council members agreed to action points on protecting the Arctic but most have never materialized.[26]

| Date(s) | City | Country |

|---|---|---|

| 17–18 September 1998 | Iqaluit | Canada |

| 13 October 2000 | Barrow | United States |

| 10 October 2002 | Inari | Finland |

| 24 November 2004 | Reykjavík | Iceland |

| 26 October 2006 | Salekhard | Russia |

| 29 April 2009 | Tromsø | Norway |

| 12 May 2011 | Nuuk | Greenland, Denmark |

| 15 May 2013 | Kiruna | Sweden |

| 24 April 2015 | Iqaluit | Canada |

| 10–11 May 2017 | Fairbanks | United States |

| 7 May 2019 | Rovaniemi | Finland |

| 19–20 May 2021 | Reykjavík | Iceland |

Chairmanship[]

Chairmanship of the Council rotates every two years.[27] The current chair is Iceland, which serves until the Ministerial meeting in 2021.[28]

- Canada (1996–1998)[29]

- United States (1998–2000)[30]

- Finland (2000–2002)[31]

- Iceland (2002–2004)[31]

- Russia (2004–2006)[31]

- Norway (2006–2009)[31]

- Denmark (2009–2011)[31][32]

- Sweden (2011–2013)[27][33]

- Canada (2013–2015)[34]

- United States (2015–2017)[30]

- Finland (2017–2019)[35][36]

- Iceland (2019–2021)

- Russia (2021–2023)

Norway, Denmark, and Sweden have agreed on a set of common priorities for the three chairmanships. They also agreed to a shared secretariat 2006–2013.[31]

The secretariat[]

Each rotating Chair nation accepts responsibility for maintaining the secretariat, which handles the administrative aspects of the Council, including organizing semiannual meetings, hosting the website, and distributing reports and documents. The Norwegian Polar Institute hosted the Arctic Council Secretariat for the six-year period from 2007 to 2013; this was based on an agreement between the three successive Scandinavian Chairs, Norway, Denmark, and Sweden. This temporary Secretariat had a staff of three.

In 2012, the Council moved towards creating a permanent secretariat in Tromsø, Norway.[4][37] (Iceland) has been the director since February 1, 2013.

The Indigenous Peoples' Secretariat[]

It is costly for the Permanent participants to be represented at every Council meeting, especially since they take place across the entire circumpolar realm. To enhance the capacity of the PPs to pursue the objectives of the Arctic Council and to assist them to develop their internal capacity to participate and intervene in Council meetings, the Council provides financial support to the Indigenous Peoples' Secretariat (IPS).[38]

The IPS board decides on the allocation of the funds. The IPS was established in 1994 under the Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy (AEPS). It was based in Copenhagen until 2016 when it relocated to Tromsø.

Working Groups, Programs and Action Plans[]

Arctic Council working groups document Arctic problems and challenges such as sea ice loss, glacier melting, tundra thawing, increase of mercury in food chains, and ocean acidification affecting the entire marine ecosystem.

The six Arctic Council workings groups:

- [39] (AMAP)

- Conservation of Arctic Flora & Fauna[40] (CAFF)

- Emergency Prevention, Preparedness & Response[41] (EPPR)

- Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment[42][43] (PAME)

- Sustainable Development Working Group[44] (SDWG)

- Arctic Contaminants Action Program (ACAP) (since 2006)[45]

Programs and Action Plans[]

- Arctic Biodiversity Assessment[46]

- Circumpolar Biodiversity Monitoring Program (CBMP)

- Arctic Climate Impact Assessment

- Arctic Human Development Report

Security and geopolitical issues[]

Before signing the Ottawa Declaration, the United States added as footnote[citation needed] "The Arctic Council should not deal with matters related to military security". In 2019 United States Secretary of State Mike Pompeo stated that circumstances had changed and "the region has become an arena for power and for competition. And the eight Arctic states must adapt to this new future".[47] The council is often in the middle of security and geopolitical issues since the Arctic has peculiar interests to Member States and Observers. Changes in the Arctic environment and participants of the Arctic Council have led to a reconsideration of the relationship between geopolitical matters and the role of the Arctic Council.

Disputes over land and ocean in the Arctic are extremely limited. The only outstanding land dispute in the Arctic is between Canada and Denmark over Hans Island. The only overlapping sea claim is between the United States and Canada in the Beaufort Sea.

The major territorial disputes are over exclusive rights to the seabed under the central Arctic high seas. Due to climate change and melting of the Arctic sea-ice, more energy resources and waterways are now becoming accessible. Large reserves of oil, gas and minerals are located within the Arctic. This environmental factor generated territorial disputes among member states. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea allows states to extend their exclusive right to exploit resources on and in the continental shelf if they can prove that seabed more 200 nautical miles (370 km; 230 mi) from baselines is a "natural prolongation" of the land. Canada, Russia, and Denmark (via Greenland) have all submitted partially overlapping claims to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS), which is charged with confirming the continental shelf's outer limits. Once the CLCS makes its rulings, Russia, Denmark and Canada will need to negotiate to divide their overlapping claims.[48]

Disputes also exist over the nature of the Northwest Passage and the Northeast Passage/Northern Sea Route. Canada claims the entire Northwest Passage is its internal waters, which means Canada would have total control over which ships may enter the channel. The United States believes the Passage is an international strait, which would mean any ship could transit at any time, and Canada could not close the Passage. Russia's claims over the Northern Sea Route are significantly different. Russia only claims small segments of the Northern Sea Route around straits as internal waters. However, Russia requires all commercial vessels to request and obtain permission to navigate in a large area of the Russian Arctic exclusive economic zone under Article 234 of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, which grants coastal states greater powers over ice-covered waters. Russia does not currently require foreign warships to request permission to pass through the Russian EEZ.

Canadian sovereignty over the Northwest Passage arouses substantial public concern in Canada. A poll indicated that half of Canadian respondents said Canada should try to assert its full sovereignty rights over the Beaufort Sea compared to just 10 percent of Americans.[49] New commercial trans-Arctic shipping routes can be another factor of conflicts. A poll found that Canadians perceive the Northwest Passage as their internal Canadian waterway whereas other countries assert it is an international waterway.[49]

The increase in the number of observer states drew attention to other national security issues. Observers have demonstrated their interests in the Arctic region. China has explicitly shown its desire to extract natural resources in Greenland.[50]

Military infrastructure is another point to consider. Canada, Denmark, Norway and Russia are rapidly increasing their defence presence by building up their militaries in the Arctic and developing their building infrastructure.[51]

However, some say that the Arctic Council facilitates stability despite possible conflicts among member states.[4] Norwegian Admiral Haakon Bruun-Hanssen has suggested that the Arctic is "probably the most stable area in the world". They say that laws are well established and followed.[50] Member states think that the sharing cost of the development of Arctic shipping-lanes, research, etc., by cooperation and good relationships between states is beneficial to all.[52]

Looking at these two different perspectives, some suggest that the Arctic Council should expand its role by including peace and security issues as its agenda. A 2010 survey showed that large majorities of respondents in Norway, Canada, Finland, Iceland, and Denmark were very supportive on the issues of an Arctic nuclear-weapons free zone.[53] Although only a small majority of Russian respondents supported such measures, more than 80 percent of them agreed that the Arctic Council should cover peace-building issues.[54] Paul Berkman suggests that solving security matters in the Arctic Council could save members the much larger amount of time required to reach a decision in United Nations. However, as of June 2014, military security matters are often avoided.[55] The focus on science and resource protection and management is seen as a priority, which could be diluted or strained by the discussion of geopolitical security issues.[56]

See also[]

- Arctic Economic Council

- Arctic cooperation and politics

- Arctic policy of Canada – Arctic Council Chair 2013–2015

- Arctic policy of the United States – Arctic Council Chair 2015–2017

- Antarctic Treaty System

- Ilulissat Declaration

- International Arctic Science Committee

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

Further reading[]

- Danita Catherine Burke. 2020. Diplomacy and the Arctic Council. McGill Queen University Press.

References[]

- ^ "Arctic Council: Founding Documents". Arctic Council Document Archive. Retrieved Sep 5, 2013.

- ^ Axworthy, Thomas S. (March 29, 2010). "Canada bypasses key players in Arctic meeting". The Toronto Star. Retrieved Sep 5, 2013.

- ^ Savage, Luiza Ch. (May 13, 2013). "Why everyone wants a piece of the Arctic". Maclean's. Rogers Digital Media. Retrieved Sep 5, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Buixadé Farré, Albert; Stephenson, Scott R.; Chen, Linling; Czub, Michael; Dai, Ying; Demchev, Denis; Efimov, Yaroslav; Graczyk, Piotr; Grythe, Henrik; Keil, Kathrin; Kivekäs, Niku; Kumar, Naresh; Liu, Nengye; Matelenok, Igor; Myksvoll, Mari; O'Leary, Derek; Olsen, Julia; Pavithran .A.P., Sachin; Petersen, Edward; Raspotnik, Andreas; Ryzhov, Ivan; Solski, Jan; Suo, Lingling; Troein, Caroline; Valeeva, Vilena; van Rijckevorsel, Jaap; Wighting, Jonathan (October 16, 2014). "Commercial Arctic shipping through the Northeast Passage: Routes, resources, governance, technology, and infrastructure". Polar Geography. 37 (4): 298–324. doi:10.1080/1088937X.2014.965769.

- ^ Lawson W Brigham (September–October 2021). "Think Again: The Arctic". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 2013-10-13. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ^ "Member States". About Us. Arctic Council. June 29, 2011. Archived from the original on September 18, 2013. Retrieved Sep 6, 2013.

- ^ Brigham, L.; McCalla, R.; Cunningham, E.; Barr, W.; VanderZwaag, D.; Chircop, A.; Santos-Pedro, V.M.; MacDonald, R.; Harder, S.; Ellis, B.; Snyder, J.; Huntington, H.; Skjoldal, H.; Gold, M.; Williams, M.; Wojhan, T.; Williams, M.; Falkingham, J. (2009). Brigham, Lawson; Santos-Pedro, V.M.; Juurmaa, K. (eds.). Arctic marine shipping assessment (AMSA) (PDF). Norway: Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment (PAME), Arctic Council. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 28, 2016.

- ^ Koring, Paul (12 May 2011). "Arctic treaty leaves much undecided". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 13 May 2011.

- ^ "About the Arctic Council". The Arctic Council. April 7, 2011. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved Sep 6, 2013.

- ^ Member States

- ^ Category: Observers (2011-04-27). "Six non-arctic countries have been admitted as observers to the Arctic Council". Arctic-council.org. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ^ "India enters Arctic Council as observer". The Hindu. 2013-05-15. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ^ Ghattas, Kim (2013-05-14). "Arctic Council: John Kerry steps into Arctic diplomacy". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ^ Thirteen Non-arctic States have been approved as Observers to the Arctic Council[permanent dead link]

- ^ "SAO meeting November 2009". Archived from the original on July 20, 2011.

- ^ [1]

- ^ "Aleut International Association". Aleut-international.org. 2012-08-23. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ^ "Arctic Athabaskan Council". Arctic Athabaskan Council. 2013-04-23. Archived from the original on 2013-09-27. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ^ "Gwich'in Council International". Gwichin.org. 2010-12-21. Archived from the original on 2018-02-15. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ^ "Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North, Siberia and the Far East". Archived from the original on August 26, 2009.

- ^ "Saami Council". Saami Council. 2009-08-24. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ^ "Arctic Parliamentarians". Arcticparl.org. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ^ "Northern Forum". Northern Forum. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ^ "Association of World Reindeer Herders". Archived from the original on September 28, 2007.

- ^ [2]

- ^ Press briefing, Arctic Council Annual Meeting, Nuuk May 2011 Stop talking – start protecting 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Troniak, Shauna (May 1, 2013). "Canada as Chair of the Arctic Council". HillNotes. Library of Parliament Research Publications. Archived from the original on June 29, 2013. Retrieved Sep 6, 2013.

- ^ "Iceland Chairs Arctic Council". Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ^ "Canadian Chairmanship Program 2013–2015". Arctic Council. Retrieved 2018-01-22.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Secretary Tillerson Chairs 10th Arctic Council Ministerial Meeting". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 2018-01-22.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "Arctic Council Secretariat". Arctic Council. Retrieved 2018-01-22.

- ^ "The Kingdom of Denmark. Chairmanship of the Arctic Council 2009–2011". Arctic Council. 2009-04-29.

- ^ "Council of American Ambassadors". Council of American Ambassadors. Retrieved 2018-01-22.

- ^ Category: About (2011-04-07). "The Norwegian, Danish, Swedish common objectives for their Arctic Council chairmanships 2006–2013". Arctic Council. Archived from the original on 2013-09-27. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ^ "The Arctic Council". Arctic Council.

- ^ "Finland's Chairmanship of the Arctic Council in 2017–2019". Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

- ^ "Travel of Deputy Secretary Burns to Sweden and Estonia". State.gov. 2012-05-14. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ^ "Terms, Reference and Guidelines" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 20, 2011.

- ^ "Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme". Amap.no. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ^ "Conservation of Arctic Flora & Fauna (CAFF)". Caff.is. Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ^ "Emergency Prevention, Preparedness & Response". Eppr.arctic-council.org. 2013-06-04. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ^ "Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment". Pame.is. 2013-06-13. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ^ User, Super. "Oops! We couldn't find this page for you". Arctic Portal.

- ^ "Sustainable Development Working Group". Portal.sdwg.org. 2013-08-27. Archived from the original on 2013-01-14. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ^ "Arctic Contaminants Action Program (ACAP)". Acap.arctic-council.org. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ^ Arctic Biodiversity Assessment Archived August 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dams, Ties; van Schaik, Louise; Stoetman, Adája (2020). Presence before power: why China became a near-Arctic state (Report). Clingendael Institute. pp. 6–19. JSTOR resrep24677.5.

- ^ Overfield, Cornell. "An Off-the-Shelf Guide to Extended Continental Shelves and the Arctic". Lawfare. Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jill Mahoney. "Canadians rank Arctic sovereignty as top foreign-policy priority". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Outsiders in the Arctic: The roar of ice cracking". The Economist. 2013-02-02. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ^ "The Arctic: Five Critical Security Challenges | ASPAmerican Security Project". Americansecurityproject.org. Archived from the original on 2013-09-27. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ^ "Arctic politics: Cosy amid the thaw". The Economist. 2012-03-24. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ^ Rethinking theTop of the World: Arctic Security Public Opinion Survey, EKOS, January 2011

- ^ Janice Gross Stein And Thomas S. Axworthy. "The Arctic Council is the best way for Canada to resolve its territorial disputes". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ^ Berkman, Paul (2014-06-23). "Stability and Peace in the Arctic Ocean through Science Diplomacy". Science & Diplomacy. 3 (2).

- ^ "U.S.-Russia Relations Are Frosty But They're Toasty On The Arctic Council". npr.org. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

External links[]

- www.arctic-council.org – Arctic Council

- Government of the Arctic

- Intergovernmental organizations

- Arctic

- Politics of Canada

- Politics of Denmark

- Politics of the Faroe Islands

- Politics of Finland

- Politics of Greenland

- Political organisations based in Greenland

- Politics of Iceland

- Political organizations based in Iceland

- Politics of Norway

- Politics of Russia

- Politics of Sweden

- Politics of the United States

- Canada–Russia relations

- Russia–United States relations

- Canada–United States relations

- Finland–Russia relations