Aviation in World War I

World War I was the first major conflict involving the large-scale use of aircraft. Tethered observation balloons had already been employed in several wars, and would be used extensively for artillery spotting. Germany employed Zeppelins for reconnaissance over the North Sea and Baltic and also for strategic bombing raids over Britain and the Eastern Front.

Aeroplanes were just coming into military use at the outset of the war. Initially, they were used mostly for reconnaissance. Pilots and engineers learned from experience, leading to the development of many specialized types, including fighters, bombers, and trench strafers.

Ace fighter pilots were portrayed as modern knights, and many became popular heroes. The war also saw the appointment of high-ranking officers to direct the belligerent nations' air war efforts.

While the impact of aircraft on the course of the war was mainly tactical rather than strategic, most important being direct cooperation with ground forces (especially ranging and correcting artillery fire), the first steps in the strategic roles of aircraft in future wars were also foreshadowed.

The early years of war[]

At the 1911 meeting of the Institute of International Law in Madrid, legislation was proposed to limit the use of aeroplanes to reconnaissance missions and banning them from being used as platforms for weapons.[1] This legislation was rooted in a fear that aeroplanes would be used to attack undefended cities, violating Article 69 of the Den Hague Reglement (the set of international laws governing warfare).[2]

At the start of the war, there was some debate over the usefulness of aircraft in warfare. Many senior officers, in particular, remained sceptical. However the initial campaigns of 1914 proved that cavalry could no longer provide the reconnaissance expected by their generals, in the face of the greatly increased firepower of twentieth century armies, and it was quickly realised that aircraft could at least locate the enemy, even if early air reconnaissance was hampered by the newness of the techniques involved. Early skepticism and low expectations quickly turned to unrealistic demands beyond the capabilities of the primitive aircraft available.[3]

Even so, air reconnaissance played a critical role in the "war of movement" of 1914, especially in helping the Allies halt the German invasion of France. On 22 August 1914, British Captain L.E.O. Charlton and Lieutenant V.H.N. Wadham reported German General Alexander von Kluck's army was preparing to surround the BEF, contradicting all other intelligence. The British High Command took note of the report and started to withdraw from Mons, saving the lives of 100,000 soldiers. Later, during the First Battle of the Marne, observation aircraft discovered weak points and exposed flanks in the German lines, allowing the allies to take advantage of them.[4]

In Germany the great successes of the early Zeppelin airships had largely overshadowed the importance of heavier-than-air aircraft. Out of a paper strength of about 230 aircraft belonging to the army in August 1914 only 180 or so were of any use.[5] The French military aviation exercises of 1911, 1912, and 1913 had pioneered cooperation with the cavalry (reconnaissance) and artillery (spotting), but the momentum was if anything slacking.[6]

Great Britain had "started late" and initially relied largely on the French aircraft industry, especially for aircraft engines. The initial British contribution to the total allied airwar effort in August 1914 (of about 184 aircraft) was three squadrons with about 30 serviceable machines. By the end of the war, Great Britain had formed the world's first air force to be independent of either army or naval control, the Royal Air Force.[7] The American army and navy air services were far behind; even in 1917, when the United States entered the war, they were to be almost totally dependent on the French and British aircraft industries for combat aircraft.[8]

The Germans' great air "coup" of 1914 was at the Battle of Tannenberg in East Prussia, where an unexpected Russian attack was reported by Leutnants Canter and Mertens, resulting in the Russians being forced to withdraw.[9]

Early Western Front reconnaissance duties[]

By the end of 1914 the line between the Germans and the Allies stretched from the North Sea to the Alps. The initial "war of movement" largely ceased, and the front became static. Three main functions of short range reconnaissance squadrons had emerged by March 1915.

The first was photographic reconnaissance: building up a complete mosaic map of the enemy trench system. The first air cameras used glass plates. (Kodak cellulose film had been invented, but did not at this stage have sufficient resolution).[10]

Artillery "spotting" enabled the ranging of artillery on targets invisible to the gunners. Radio telephony was not yet practical from an aircraft, so communication was a problem. By March 1915, a two-seater on "artillery observation" duties was typically equipped with a primitive radio transmitter transmitting using Morse code, but had no receiver. The artillery battery signalled to the aircraft by laying strips of white cloth on the ground in prearranged patterns. Observation duties were shared with the tethered balloons, which could communicate directly with their batteries by field telephone, but were far less flexible in locating targets and reporting the fall of shot.

"Contact patrol" work attempted to follow the course of a battle by communicating with advancing infantry while flying over the battlefield. The technology of the period did not permit radio contact, while methods of signalling were necessarily crude, including dropping messages from the aircraft. Soldiers were initially reluctant to reveal their positions to aircraft, as they (the soldiers) found distinguishing between friend and foe problematic.

Reconnaissance flying, like all kinds, was a hazardous business. In April 1917, the worst month for the entire war for the RFC (Royal Flying Corps), the average life expectancy of a British pilot on the Western Front was 69 flying hours.[11]

Early bombing efforts[]

Typical 1914 aircraft could carry only very small bomb loads – the bombs themselves, and their stowage, were still very elementary, and effective bomb sights were still to be developed. Nonetheless the beginnings of strategic and tactical bombing date from the earliest days of the war. Notable are the raids by the RNAS on the German airship sheds at Düsseldorf, Cologne and Friedrichshafen in September, October and November 1914, as well as the formation of the Brieftauben Abteilung Ostende.

The dawn of air combat[]

As Dickson had predicted, initially air combat was extremely rare, and definitely subordinate to reconnaissance. There are even stories of the crew of rival reconnaissance aircraft exchanging nothing more belligerent than smiles and waves.[10] This soon progressed to throwing grenades, and other objects – even grappling hooks.[12] The first aircraft brought down by another was an Austrian reconnaissance aircraft rammed on 8 September 1914 by Russian pilot Pyotr Nesterov in Galicia in the Eastern Front. Both planes crashed as the result of the attack killing all occupants. Eventually pilots began firing handheld firearms at enemy aircraft,[10] however pistols were too inaccurate and the single shot rifles too unlikely to score a hit. On October 5, 1914, French pilot Louis Quenault opened fire on a German aircraft with a machine gun for the first time and the era of air combat was under way as more and more aircraft were fitted with machine guns.

Evolution of fighter aircraft[]

The pusher solution[]

As early as 1912, designers at the British firm Vickers were experimenting with machine gun carrying aircraft. The first concrete result was the Vickers Experimental Fighting Biplane 1, which featured at the 1913 Aero Show in London.[13] and appeared in developed form as the FB.5 in February 1915. This pioneering fighter, like the Royal Aircraft Factory F.E.2b and the Airco DH.1, was a pusher type. These had the engine and propeller behind the pilot, facing backward, rather than at the front of the aircraft, as in a tractor configuration design. This provided an optimal machine gun position, from which the gun could be fired directly forward without an obstructing propeller, and reloaded and cleared in flight. An important drawback was that pusher designs tended to have an inferior performance to tractor types with the same engine power because of the extra drag created by the struts and rigging necessary to carry the tail unit. The F.E.2d, a more powerful version of the F.E.2b, remained a formidable opponent well into 1917, when pusher fighters were already obsolete. They were simply too slow to catch their quarry.

Machine gun synchronisation[]

The forward firing gun of a pusher "gun carrier" provided some offensive capability – the mounting of a machine gun firing to the rear from a two-seater tractor aircraft gave defensive capability. There was an obvious need for some means to fire a machine gun forward from a tractor aircraft, especially from one of the small, light, "scout" aircraft, adapted from pre-war racers, that were to perform most air combat duties for the rest of the war. It would seem most natural to place the gun between the pilot and the propeller, firing in the direct line of flight, so that the gun could be aimed by "aiming the aircraft". It was also important that the breech of the weapon be readily accessible to the pilot, so that he could clear the jams and stoppages to which early machine guns were prone. However, this presented an obvious problem: a percentage of bullets fired "free" through a revolving propeller will strike the blades, with predictable results. Early experiments with synchronised machine guns had been carried out in several countries before the war. Franz Schneider, then working for Nieuport in France but later working for L.V.G. in Germany, patented a synchronisation gear on 15 July 1913. An early Russian gear was designed by a Lieutenant Poplavko: the Edwards brothers in England designed the first British example, and the Morane-Saulnier company were also working on the problem in 1914. All these early experiments failed to attract official attention, partly due to official inertia and partly due to the failures of early synchronising gears, which included dangerously ricocheting bullets and disintegrating propellers.[14] The Lewis gun used on many Allied aircraft was almost impossible to synchronise due to the erratic rate of fire due to its open bolt firing cycle. Some RNAS aircraft, including Bristol Scouts, had an unsynchronised fuselage-mounted Lewis gun positioned to fire directly through the propeller disk, however these were often not synchronized. Instead the prop blades were reinforced with tape to hold the wood together if hit, and it relied on the fact that the odds of any single round hitting a blade below 5%, so if short bursts were used, it offered a temporary expedient even if it was not an ideal solution.

The Maxim guns used by both the Allies (as the Vickers) and Germany (as the Parabellum MG 14 and Spandau lMG 08) had a closed bolt firing cycle that started with a bullet already in the breech and the breech closed, so the firing of the bullet was the next step in the cycle. This meant that the exact instant the round would be fired could be more readily predicted, making these weapons considerably easier to synchronise. The standard French light machine gun, the Hotchkiss, was, like the Lewis, also unamenable to synchronisation. Poor quality control also hampered efforts, resulting in frequent "hang fire" rounds that didn't go off. The Morane-Saulnier company designed a "safety backup" in the form of "deflector blades" (metal wedges), fitted to the rear surfaces of a propeller at the radial point where they could be struck by a bullet. Roland Garros used this system in a Morane-Saulnier L in April 1915. He managed to score several kills, although the deflectors fell short of an ideal solution as the deflected rounds could still cause damage. Engine failure eventually forced Garros to land behind enemy lines, and he and his secret weapon were captured by the Germans.[15] Famously, the German High Command passed Garros' captured Morane to the Fokker company – who already produced Morane type monoplanes for the German Air Service – with orders to copy the design. The deflector system was totally unsuitable for the steel-jacketed German ammunition so that the Fokker engineers were forced to revisit the synchronisation idea (perhaps infringing Schneider's patent), crafting the Stangensteuerung system by the spring of 1915, used on the examples of their pioneering Eindecker fighter. Crude as these little monoplanes were, they produced a period of German air superiority, known as the "Fokker Scourge" by the Allies. The psychological effect exceeded the material – the Allies had up to now been more or less unchallenged in the air, and the vulnerability of their older reconnaissance aircraft, especially the British B.E.2 and French Farman pushers, came as a very nasty shock.

Other methods[]

Another method used at this time to fire a machine gun forward from a tractor design was to mount the gun to fire above the propeller arc. This required the gun to be mounted on the top wing of biplanes and be mounted on complicated drag-inducing structures in monoplanes. Reaching the gun so that drums or belts could be changed, or jams cleared, presented problems even when the gun could be mounted relatively close to the pilot. Eventually, Foster mounting became more or less the standard way of mounting a Lewis gun in this position in the R.F.C.:[16] this allowed the gun to slide backward for drum changing, and also to be fired at an upward angle, a very effective way of attacking an enemy from the "blind spot" under its tail. This type of mounting was still only possible for a biplane with a top wing positioned near the apex of the propeller's arc – it put considerable strain on the fragile wing structures of the period, and it was less rigid than a gun mounting on the fuselage, producing a greater "scatter" of bullets, especially at anything but very short range.

The earliest versions of the Bristol Scout to see aerial combat duty in 1915, the Scout C, had Lewis gun mounts in RNAS service that sometimes were elevated above the propeller arc, and sometimes (in an apparently reckless manner) firing directly through the propeller arc without synchronisation. During the spring and summer of 1915, Captain Lanoe Hawker of the Royal Flying Corps, however, had mounted his Lewis gun just forward of the cockpit to fire forwards and outwards, on the left side of his aircraft's fuselage at about a 30° horizontal angle. On 25 July 1915 Captain Hawker flew his Scout C, bearing RFC serial number 1611 against several two-seat German observation aircraft of the Fliegertruppe, and managed to defeat three of them in aerial engagements to earn the first Victoria Cross awarded to a British fighter pilot, while engaged against enemy fixed-wing aircraft.

1915: The Fokker Scourge[]

The first purpose-designed fighter aircraft included the British Vickers F.B.5, and machine guns were also fitted to several French types, such as the Morane-Saulnier L and N. Initially the German Air Service lagged behind the Allies in this respect, but this was soon to change dramatically.

In July 1915 the Fokker E.I, the first aircraft to enter service with a "synchronisation gear" which enabled a machine gun to fire through the arc of the propeller without striking its blades, became operational. This gave an important advantage over other contemporary fighter aircraft. This aircraft and its immediate successors, collectively known as the Eindecker (German for "monoplane") – for the first time supplied an effective equivalent to Allied fighters. Two German military aviators, Leutnants Otto Parschau and Kurt Wintgens, worked for the Fokker firm during the spring of 1915, demonstrating the revolutionary feature of the forward-firing synchronised machine gun to the embryonic force of Fliegertruppe pilots of the German Empire.

The first successful engagement involving a synchronised-gun-armed aircraft occurred on the afternoon of July 1, 1915, to the east of Lunéville, France when Leutnant Kurt Wintgens, one of the pilots selected by Fokker to demonstrate the small series of five Eindecker prototype aircraft, forced down a French Morane-Saulnier "Parasol" two seat observation monoplane behind Allied lines with his Fokker M.5K/MG Eindecker production prototype aircraft, carrying the IdFlieg military serial number "E.5/15". Some 200 shots from the synchronised Parabellum MG14 machine gun on Wintgens' aircraft had hit the Gnome Lambda rotary engine of the Morane Parasol, forcing it to land safely in Allied territory.[17]

By late 1915 the Germans had achieved air superiority, rendering Allied access to the vital intelligence derived from continual aerial reconnaissance more dangerous to acquire. In particular the defencelessness of Allied reconnaissance types was exposed. The first German "ace" pilots, notably Max Immelmann, had begun their careers.

The number of actual Allied casualties involved was for various reasons very small compared with the intensive air fighting of 1917–18. The deployment of the Eindeckers was less than overwhelming: the new type was issued in ones and twos to existing reconnaissance squadrons, and it was to be nearly a year before the Germans were to follow the British in establishing specialist fighter squadrons. The Eindecker was also, in spite of its advanced armament, by no means an outstanding aircraft, being closely based on the pre-war Morane-Saulnier H, although it did feature a steel tubing fuselage framework (a characteristic of all Fokker wartime aircraft designs) instead of the wooden fuselage components of the French aircraft.

Nonetheless, the impact on morale of the fact that the Germans were effectively fighting back in the air created a major scandal in the British parliament and press. The ascendancy of the Eindecker also contributed to the surprise the Germans were able to achieve at the start of the Battle of Verdun because the French reconnaissance aircraft failed to provide their usual cover of the German positions.

Fortunately for the Allies, two new British fighters that were a match for the Fokker, the two-seat F.E.2b and the single-seat D.H.2, were already in production. These were both pushers, and could fire forwards without gun synchronisation. The F.E.2b reached the front in September 1915, and the D.H.2 in the following February. On the French front, the tiny Nieuport 11, a tractor biplane with a forward firing gun mounted on the top wing outside the arc of the propeller, also proved more than a match for the German fighter when it entered service in January 1916. With these new types the Allies re-established air superiority in time for the Battle of the Somme, and the "Fokker Scourge" was over.

The Fokker E.III, Airco DH-2 and Nieuport 11 were the very first in a long line of single seat fighter aircraft used by both sides during the war. Very quickly it became clear the primary role of fighters would be attacking enemy two-seaters, which were becoming increasingly important as sources of reconnaissance and artillery observation, while also escorting and defending friendly two-seaters from enemy fighters. Fighters were also used to attack enemy observation balloons, strafe enemy ground targets, and defend friendly airspace from enemy bombers.

Almost all the fighters in service with both sides, with the exception of the Fokkers' steel-tube fuselaged airframes, continued to use wood as the basic structural material, with fabric-covered wings relying on external wire bracing. However, the first practical all-metal aircraft was produced by Hugo Junkers, who also used a cantilever wing structure with a metal covering. The first flight tests of the initial flight demonstrator of this technology, the Junkers J 1 monoplane, took place at the end of 1915 heralding the future of aircraft structural design.

1916: Verdun and the Somme[]

Creating new units was easier than producing aircraft to equip them, and training pilots to man them. When the Battle of the Somme started in July 1916, most ordinary RFC squadrons were still equipped with planes that proved easy targets for the Fokker. New types such as the Sopwith 1½ Strutter had to be transferred from production intended for the RNAS. Even more seriously, replacement pilots were being sent to France with pitifully few flying hours.

Nonetheless, air superiority and an "offensive" strategy facilitated the greatly increased involvement of the RFC in the battle itself, in what was known at the time as "trench strafing" – in modern terms, close support. For the rest of the war, this became a regular routine, with both attacking and defending infantry in a land battle being constantly liable to attack by machine guns and light bombs from the air. At this time, counter fire from the ground was far less effective than it became later, when the necessary techniques of deflection shooting had been mastered.

The first step towards specialist fighter-only aviation units within the German military was the establishment of the so-called Kampfeinsitzer Kommando (single-seat battle unit, abbreviated as "KEK") formations by Inspektor-Major Friedrich Stempel in February 1916. These were based around Eindeckers and other new fighter designs emerging, like the Pfalz E-series monoplanes, that were being detached from their former Feldflieger Abteilung units during the winter of 1915–16 and brought together in pairs and quartets at particularly strategic locations, as "KEK" units were formed at Habsheim, Vaux, Avillers, Jametz, and Cunel, as well as other strategic locations along the Western Front to act as Luftwachtdienst (aerial guard force) units, consisting only of fighters.[18] In a pioneering move in March 1916, German master aerial tactician Oswald Boelcke came up with the idea of having "forward observers" located close to the front lines to spot Allied aircraft approaching the front, to avoid wear and tear on the trio of Fokker Eindecker scout aircraft he had based with his own "KEK" unit based at Sivry-sur-Meuse,[19] just north of Verdun. By April 1916, the air superiority established by the Eindecker pilots and maintained by their use within the KEK formations had long evaporated as the Halberstadt D.II began to be phased in as Germany's first biplane fighter design, with the first Fokker D-series biplane fighters joining the Halberstadts, and a target was set to establish 37 new squadrons in the next 12 months – entirely equipped with single seat fighters, and manned by specially selected and trained pilots, to counter the Allied fighter squadrons already experiencing considerable success, as operated by the Royal Flying Corps and the French Aéronautique Militaire. The small numbers of questionably built Fokker D.IIIs posted to the Front pioneered the mounting of twin lMG 08s before 1916's end, as the building numbers of the similarly armed, and much more formidable new twin-gun Albatros D.Is were well on the way to establishing the German air superiority marking the first half of 1917.

Allied air superiority was maintained during the height of both battles, and the increased effectiveness of Allied air activity proved disturbing to the German Army's top-level Oberste Heeresleitung command staff.[20] A complete reorganisation of the Fliegertruppen des deutschen Kaiserreiches into what became officially known as the Luftstreitkräfte followed and had generally been completed by October 1916. This reorganisation eventually produced the German strategic bombing squadrons that were to produce such consternation in England in 1917 and 1918, and the specialist close support squadrons (Schlachtstaffeln) that gave the British infantry such trouble at Cambrai and during the German spring offensive of 1918. Its most famous and dramatic effect, however, involved the raising of specialist fighter squadrons or Jagdstaffeln – a full year after similar units had become part of the RFC and the French Aéronautique Militaire. Initially these units were equipped with the Halberstadt D.II (Germany's first biplane fighter), the Fokker D.I and D.II, along with the last few surviving Eindeckers, all three biplane design types using a single lMG 08, before the Fokker D.III and Albatros D.I twin-gun types arrived at the Front.

1917: Bloody April[]

The first half of 1917 was a successful period for the jagdstaffeln and the much larger RFC suffered significantly higher casualties than their opponents. While new Allied fighters such as the Sopwith Pup, Sopwith Triplane, and SPAD S.VII were coming into service, at this stage their numbers were small, and suffered from inferior firepower: all three were armed with just a single synchronised Vickers machine gun. On the other hand, the jagdstaffeln were in the process of replacing their early motley array of equipment with aircraft, armed with twin synchronised MG08s. The D.I and D.II of late 1916 were succeeded by the new Albatros D.III, which was, in spite of structural difficulties, "the best fighting scout on the Western Front"[21] at the time. Meanwhile, most RFC two-seater squadrons still flew the BE.2e, a very minor improvement on the BE.2c, and still fundamentally unsuited to air-to-air combat.

This culminated in the rout of April 1917, known as "Bloody April". The RFC suffered particularly severe losses, although Trenchard's policy of "offensive patrol", which placed most combat flying on the German side of the lines, was maintained.[22]

During the last half of 1917, the British Sopwith Camel and S.E.5a and the French SPAD S.XIII, all fitted with two forward firing machine guns, became available in numbers. The ordinary two seater squadrons in the RFC received the R.E.8 or the F.K.8, not outstanding warplanes, but far less vulnerable than the BE.2e they replaced. The F.E.2d at last received a worthy replacement in the Bristol F.2b. On the other hand, the latest Albatros, the D.V, proved to be a disappointment, as was the Pfalz D.III. The exotic Fokker Dr.I was plagued, like the Albatros, with structural problems. By the end of the year the air superiority pendulum had swung once more in the Allies' favour.

1918 – the Spring Offensive[]

The surrender of the Russians and the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918, and the resulting release of troops from the Eastern Front gave the Germans a "last chance" of winning the war before the Americans could become effectively involved. This resulted in the last great German offensive of the war, the "Spring Offensive", which opened on 21 March. The main attack fell on the British front on the assumption that defeat of the British army would result in the surrender of the mutiny-weakened French.[23]

In the air, the battle was marked by the carefully coordinated use of the Schlachtstaffeln or "battle flights", equipped with the light CL class two seaters built by the Halberstadt and Hannover firms, that had proved so effective in the German counter-attack in early October's Battle of Cambrai.[24] The new German fighter aircraft, notably the Fokker D.VII, that might have revived German air superiority in time for this battle had not however reached the Jagdstaffeln in sufficient numbers, despite its own premier on the Western Front in the mid-Spring of 1918. As with several offensives on both sides, thorough planning and preparation led to initial success, and in fact to deeper penetration than had been achieved by either side since 1914.[25] Many British airfields had to be abandoned to the advancing Germans in a new war of movement. Losses of aircraft and their crew were very heavy on both sides – especially to light anti-aircraft fire. However, by the time of the death of Manfred von Richthofen, the famed Red Baron, on 21 April, the great offensive had largely stalled.[26] The new German fighters had still not arrived, and the British still held general air superiority.

The month of April 1918 began with the consolidation of the separate British RFC and RNAS air services into the Royal Air Force, the first independent air arm not subordinate to its national army or navy. By the end of April, the new Fokker, Pfalz and Roland fighters had finally begun to replace the obsolescent equipment of the Jagdstaffeln, but this did not proceed with as much dispatch as it might have, due to increasing shortages of supplies on the side of the Central Powers, and many of the Jastas still flew Albatros D types at the time of the armistice. The rotary engined Fokker D.VIII and Siemens-Schuckert D.IV, as well as surviving Fokker Triplanes, suffered from poor reliability and shortened engine life due to the Voltol-based oil that was used to replace scarce castor oil – captured and salvaged Allied aircraft (especially Sopwith Camels) were scrounged, not only for engines and equipment, but even for their lubricants. Nonetheless, by September, casualties in the RFC had reached the highest level since "Bloody April"[27] – and the Allies were maintaining air superiority by weight of numbers rather than technical superiority.

Readying for battle[]

1918, especially the second half of the year, also saw the United States increasingly involved with the allied aerial efforts. While American volunteers had been flying in Allied squadrons since the early years of the war, not until 1918 did all-American squadrons begin active operations. Technically America had fallen well behind the European powers in aviation, and no American designed types saw action, with the exception of the Curtiss flying boats. At first, the Americans were supplied with second-rate and obsolete aircraft, such as the Sopwith 1½ Strutter, Dorand AR and Sopwith Camel, and inexperienced American airmen stood little chance against their seasoned opponents.

General John J. Pershing assigned Major General Mason Patrick as Chief of the US Air Service to remedy these issues in May 1918.[28] As numbers grew and equipment improved with the introduction of the twin-gun Nieuport 28, and later, SPAD XIII as well as the S.E.5a into American service near the war's end, the Americans came to hold their own in the air; although casualties were heavy, as indeed were those of the French and British, in the last desperate fighting of the war. One of the French twin-seat reconnaissance aircraft used by both the French and the USAAS, was the radial powered Salmson 2 A.2.

Leading up to the Battle of Saint-Mihiel, The US Air Service under Maj. Gen. Patrick oversaw the organization of 28 air squadrons for the battle, with the French, British, and Italians contributing additional units to bring the total force numbers to 701 pursuit planes, 366 observation planes, 323 day bombers, and 91 night bombers. The 1,481 total aircraft made it the largest air operation of the war.[29][30]

Impact[]

The day has passed when armies on the ground or navies on the sea can be the arbiter of a nation's destiny in war. The main power of defense and the power of initiative against an enemy has passed to the air.

— Brigadier General Billy Mitchell, November 1918[31]

By war's end, the impact of aerial missions on the ground war was in retrospect mainly tactical; strategic bombing, in particular, was still very rudimentary indeed. This was partly due to its restricted funding and use, as it was, after all, a new technology. On the other hand, the artillery, which had perhaps the greatest effect of any military arm in this war, was in very large part as devastating as it was due to the availability of aerial photography and aerial "spotting" by balloon and aircraft. By 1917 weather bad enough to restrict flying was considered as good as "putting the gunner's eyes out".[32]

Some, such as then-Brigadier General Billy Mitchell, commander of all American air combat units in France, claimed, "[T]he only damage that has come to [Germany] has been through the air".[33] Mitchell was famously controversial in his view that the future of war was not on the ground or at sea, but in the air.

During the course of the War, German aircraft losses accounted to 27,637 by all causes, while Entente losses numbered over 88,613 lost (52,640 France & 35,973 Great Britain)[34]

Anti-aircraft weaponry[]

Though aircraft still functioned as vehicles of observation, increasingly they were used as a weapon in themselves. Dog fights erupted in the skies over the front lines, and aircraft went down in flames. From this air-to-air combat, the need grew for better aircraft and gun armament. Aside from machine guns, air-to-air rockets were also used, such as the Le Prieur rocket against balloons and airships. Recoilless rifles and autocannons were also attempted, but they pushed early fighters to unsafe limits while bringing negligible returns, with the German Becker 20mm autocannon being fitted to a few twin-engined Luftstreitkräfte G-series medium bombers for offensive needs, and at least one late-war Kaiserliche Marine zeppelin for defense – the uniquely armed SPAD S.XII single-seat fighter carried one Vickers machine gun and a special, hand-operated semi-automatic 37mm gun firing through a hollow propeller shaft.[35] Another innovation was air-to-air bombing if a fighter had been fortunate enough to climb higher than an airship. The Ranken dart was designed just for this opportunity.

This need for improvement was not limited to air-to-air combat. On the ground, methods developed before the war were being used to deter enemy aircraft from observation and bombing. Anti-aircraft artillery rounds were fired into the air and exploded into clouds of smoke and fragmentation, called archie by the British.

Anti-aircraft artillery defenses were increasingly used around observation balloons, which became frequent targets of enemy fighters equipped with special incendiary bullets. Because balloons were so flammable, due to the hydrogen used to inflate them, observers were given parachutes, enabling them to jump to safety. Ironically, only a few aircrew had this option, due in part to a mistaken belief they inhibited aggressiveness, and in part to their significant weight.

First shooting-down of an aeroplane by anti-aircraft artillery[]

During a bombing raid over Kragujevac on 30 September 1915, private Radoje Ljutovac of the Serbian Army successfully shot down one of the three aircraft. Ljutovac used a slightly modified Turkish cannon captured some years previously. This was the first time that a military aeroplane was shot down with ground-to-air artillery fire, and thus a crucial moment in anti-aircraft warfare.[36][37][38]

Bombing and reconnaissance[]

As the stalemate developed on the ground, with both sides unable to advance even a few hundred yards without a major battle and thousands of casualties, aircraft became greatly valued for their role gathering intelligence on enemy positions and bombing the enemy's supplies behind the trench lines. Large aircraft with a pilot and an observer were used to scout enemy positions and bomb their supply bases. Because they were large and slow, these aircraft made easy targets for enemy fighter aircraft. As a result, both sides used fighter aircraft to both attack the enemy's two-seat aircraft and protect their own while carrying out their missions.

While the two-seat bombers and reconnaissance aircraft were slow and vulnerable, they were not defenseless. Two-seaters had the advantage of both forward- and rearward-firing guns. Typically, the pilot controlled fixed guns behind the propeller, similar to guns in a fighter aircraft, while the observer controlled one with which he could cover the arc behind the aircraft. A tactic used by enemy fighter aircraft to avoid fire from the rear gunner was to attack from slightly below the rear of two-seaters, as the tail gunner was unable to fire below the aircraft. However, two-seaters could counter this tactic by going into a dive at high speeds. Pursuing a diving two-seater was hazardous for a fighter pilot, as it would place the fighter directly in the rear gunner's line of fire; several high scoring aces of the war were shot down by "lowly" two-seaters, including Raoul Lufbery, Erwin Böhme, and Robert Little. Even Manfred von Richthofen, the highest scoring ace of WWI, was once wounded and forced to crash land from the bullets of a two-seater, though he did survive the encounter and continued flying after he recovered.

Strategic bombing[]

The first aerial bombardment of civilians occurred during World War I. In the opening weeks of the war, zeppelins bombed Liège, Antwerp, and Warsaw, and other cities, including Paris and Bucharest, were targeted, In January 1915 the Germans began a bombing campaign against England that was to last until 1918, initially using airships. There were 19 raids in 1915, in which 37 tons of bombs were dropped, killing 181 people and injuring 455. Raids continued in 1916. London was accidentally bombed in May, and in July, the Kaiser allowed directed raids against urban centres. There were 23 airship raids in 1916 in which 125 tons of ordnance were dropped, killing 293 people and injuring 691. Gradually British air defenses improved. In 1917 and 1918 there were only eleven Zeppelin raids against England, and the final raid occurred on 5 August 1918, resulting in the death of Peter Strasser, commander of the German Naval Airship Department. By the end of the war, 54 airship raids had been undertaken, in which 557 people were killed and 1,358 injured.[39] Of the 80 airships used by the Germans in World War I, 34 were shot down and further 33 were destroyed by accidents. 389 crewmen died.[40]

The Zeppelin raids were complemented by the Gotha G bombers from 1917, which were the first heavier than air bombers to be used for strategic bombing, and by a small force of five Zeppelin-Staaken R.VI "giant" four engined bombers from late September 1917 through to mid-May 1918. Twenty-four Gotha twin-engined bombers were shot down on the raids over England, with no losses for the Zeppelin-Staaken giants. Further 37 Gotha bombers crashed in accidents.[40] They dropped 73 tons of bombs, killing 857 people and wounding 2058.[40]

It has been argued that the raids were effective far beyond material damage in diverting and hampering wartime production, and diverting twelve squadrons and over 17,000 men to air defenses.[41] Calculations performed on the number of dead to the weight of bombs dropped had a profound effect on attitudes of the British government and population in the interwar years, who believed that "The bomber will always get through".

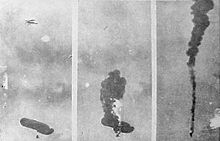

Observation balloons[]

Manned observation balloons floating high above the trenches were used as stationary reconnaissance points on the front lines, reporting enemy troop positions and directing artillery fire. Balloons commonly had a crew of two equipped with parachutes: upon an enemy air attack on the flammable balloon, the crew would parachute to safety. Recognized for their value as observer platforms, observation balloons were important targets of enemy aircraft. To defend against air attack, they were heavily protected by large concentrations of antiaircraft guns and patrolled by friendly aircraft. Blimps and balloons helped contribute to the stalemate of the trench warfare of World War I, and contributed to air-to-air combat for air superiority because of their significant reconnaissance value.

To encourage pilots to attack enemy balloons, both sides counted downing an enemy balloon as an "air-to-air" kill, with the same value as shooting down an enemy aircraft. Some pilots, known as balloon busters, became particularly distinguished by their prowess at shooting down enemy balloons. The premier balloon busting ace was Willy Coppens: 35 of his 37 victories were enemy balloons.

Leading aces[]

As pioneer aviators invented air-to-air combat, the contending sides developed various methods of tracking aerial casualties and victories. Aviators with five or more aerial victories confirmed by their parent air service were dubbed "aces". Their numbers would burgeon, until by war's end, there were over 1,800 aces.

The following aces scored the most victories for their respective air services.

| Name | Air service | Confirmed victories |

|---|---|---|

| Baracca, Francesco | Corpo Aeronautico Militare | 34[42] |

| Bishop, William Avery | Royal Air Force | 72[43] |

| Brumowski, Godwin | Luftfahrtruppen | 35[44] |

| Cobby, Arthur Henry | Australian Flying Corps | 29[citation needed] |

| Coppens de Houthulst, Willy Omer | Belgian Military Aviation | 37[45] |

| Fonck, René | Aéronautique Militaire | 75[46] |

| Kazakov, Alexander | Imperial Russian Air Force | 20[47] |

| Richthofen, Manfred von | Luftstreitkräfte | 80[48] |

| Rickenbacker, Edward Vernon | US Army Air Service | 26[49][50] |

Pioneers of aerial warfare[]

The following aviators were the first to reach important milestones in the development of aerial combat during World War I:

| Name | Date | Country | Event |

|---|---|---|---|

| Miodrag Tomić | 12 August 1914 | Serbia | First dogfight of the war[51][52] |

| Pyotr Nesterov | 7 September 1914 | Russia | First air-to-air kill, by ramming an Austrian aeroplane[53] |

| Louis Quénault and Joseph Frantz | 5 October 1914 | France | Pilot Frantz and Observer Quénault were the first fliers to successfully use a machine gun in air-to-air combat to shoot down another aircraft.[54] |

| Roland Garros | 1 April 1915 | France | First aerial victory with forward pointing fixed gun achieved while aiming gun with aircraft[55] |

| Adolphe Pégoud | 3 April 1915 | France | First flying "ace" and first French ace.[56] |

| Kurt Wintgens | 1 July 1915 | Germany | First aerial victory using a sychronised machine gun firing through the propeller arc[57] |

| Lanoe Hawker | 11 August 1915 | United Kingdom | First British ace.[58] |

| Oswald Boelcke | 16 October 1915 | Germany | First German ace.[59] |

| Otto Jindra | 9 April 1916 | Austria-Hungary | First Austro-Hungarian ace.[60] |

| Redford Henry Mulock | 21 May 1916 | Canada | First Canadian ace, as well as first Royal Naval Air Service ace.[61] |

| Eduard Pulpe | 1 July 1916 | Russia | First Imperial Russian Air Force ace.[62] |

| Roderic Dallas | 9 July 1916 | Australia | First Australian ace.[63] |

| Frederick Libby | 25 August 1916 | United States | First American ace.[64] |

| Etienne Tsu | 26 September 1916 | France | First Chinese ace; French Foreign Legion, Escadrille SPA.37.[65][66] |

| Mario Stoppani | 31 October 1916 | Italy | First Italian ace.[67] |

| Fernand Jacquet | 1 February 1917 | Belgium | First Belgian ace.[68] |

| Maurice Benjamin | 27 April 1917 | South Africa | First South African ace.[69] |

| Thomas Culling | 19 May 1917 | New Zealand | First New Zealand ace.[70] |

| Gottfried Freiherr von Banfield | 31 May 1917 | Austria-Hungary | First night victory and first Austro-Hungarian night victory.[71] |

| Richard Burnard Munday | 29 September 1917 | United Kingdom | First British night victory, over an observation balloon.[72] |

| Fritz Anders | 20 August 1918 | Germany | First German night victory. Anders was first night fighter ace.[73] |

Aircraft[]

- Aircraft of the Entente Powers

- Aircraft of the Central Powers

See also[]

- Biggles a fictional WWI aviator

- Biplane

- Dogfight

- Flying ace § World War I

- History of aerial warfare

- History of aviation

- List of American aero squadrons

- List of Royal Air Force aircraft squadrons

- List of Royal Flying Corps squadrons

- Lists of World War I flying aces

Notes[]

- ^ Spaight, James (1914). Aircraft In War. London: MacMilian and Co. p. 3.

- ^ Spaight, James (1914). Aircraft in War. London: MacMilian and Co. p. 14.

- ^ Terraine, John. P.30

- ^ "Aerial Reconnaissance in World War I". U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ Terraine, 1981, p.31.

- ^ Terraine, 1981, p.30

- ^ Terraine, 1982, p.31

- ^ Treadwell, Terry C. America's First Air War (London: Airlife Publishing, 2000)

- ^ Cheesman, E.F. (ed.) Reconnaissance & Bomber Aircraft of the 1914–1918 War (Letchworth, UK: Harleyford, 1962), p. 9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c An Illustrated History of World War I, at http://www.wwiaviation.com/earlywar.html

- ^ Eric Lawson; Jane Lawson (2007). The First Air Campaign: August 1914 – November 1918. Da Capo Press, Incorporated. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-306-81668-0.

- ^ Great Battles of World War I by Major-General Sir Jeremy Moore, p. 136

- ^ Cheesman (1960), p. 76.

- ^ Cheesman (1960), p 177

- ^ Cheesman (1960), p 178

- ^ Cheesman (1960), p 180

- ^ Sands, Jeffrey, "The Forgotten Ace, Ltn. Kurt Wintgens and his War Letters", Cross & Cockade USA, Summer 1985.

- ^ Guttman, Jon (Summer 2009). "Verdun: The First Air Battle for the Fighter: Part I – Prelude and Opening" (PDF). worldwar1.com. The Great War Society. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 3, 2016. Retrieved May 26, 2014.

- ^ vanWyngarden, Greg (2006). Osprey Aircraft of the Aces #73: Early German Aces of World War 1. Botley, Oxford UK & New York City, USA: Osprey Publishing. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-84176-997-4.

- ^ Cheesman (1960) p.12

- ^ Fitzsimons, Bernard, ed. The Twentieth Century Encyclopedia of Weapons and Warfare (London: Phoebus, 1978), Volume 1, "Albatros D", p.65

- ^ Johnson in History of Air Fighting blames Trenchard for not changing his approach despite the prohibitive casualties.

- ^ Terraine, 1982 p. 277

- ^ Gray & Theyford, 1970 pp. xv–xxvii

- ^ Terraine, 1982 p.282

- ^ Terraine, 1982 p.287

- ^ Harris & Pearson, 2010 p.180

- ^ Tate, Dr. James P. (1998). The Army and its Air Corps: Army Policy Toward Aviation 1919–1941, Air University Press, p. 19

- ^ Frandsen, Bert (2014). "Learning and Adapting: Billy Mitchell in World War I". National Defense University Press. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ DuPre, Flint. "U.S. Air Force Biographical Dictionary". United States Air Force. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- ^ This quote was also mentioned in Time magazine, 22 June 1942 [1], some seven months after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, which Mitchell accurately predicted in 1924.

- ^ Terraine, 1982, p. 215

- ^ "Mitchell">"Leaves From My War Diary" by General William Mitchell, in Great Battles of World War I: In The Air (Signet, 1966), pp.192–193 (November 1918).

- ^ "The Aircraft of World War I – Statistics". Theaerodrome.com. Retrieved 2015-12-17.

- ^ Guttman, Jon (2002). SPAD XII/XIII aces of World War I. Osprey Publishing. pp. 8–9. ISBN 1841763160.

- ^ "How was the first military aeroplane shot down". National Geographic. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ^ "Ljutovac, Radoje". Amanet Society. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ^ "Radoje Raka Ljutovac – first person in the world to shoot down an aeroplane with a cannon". Pečat. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ^ Cole, Christopher; Cheesman, E. F. (1984). The Air Defence of Great Britain 1914–1918. London: Putnam. pp. 448–9. ISBN 0 370 30538 8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Clodfelter, Micheal (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015. McFarland. p. 430.

- ^ Ben Walsh AQA GCSE Modern World History p296

- ^ Franks, 2000. p. 76

- ^ Shores, 2001. p. 89

- ^ Chant, 2002. p. 90

- ^ Franks, 2000. p. 71

- ^ Guttman, 2002. p. 20

- ^ Franks, 2000. pp. 83–84

- ^ Franks, Bailey, Guest, 1993. pp. 241–242

- ^ Franks, 2000. p. 74

- ^ Franks, 2001. p. 86

- ^ Glenny, Misha (2012). The Balkans: 1804–2012. New York City: Granta. p. 316. ISBN 978-1-77089-273-6.

- ^ Buttar, Prit (2014). Collision of Empires: The War on the Eastern Front in 1914. Oxford, England: Osprey Publishing. p. 298. ISBN 978-1-78200-648-0.

- ^ Guttman, p. 9.

- ^ Jackson 1993, p. 24

- ^ van Wyngarden, pp. 7, 8, 11.

- ^ "Adolphe Pégoud". theaerodrome.com. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ "Kurt Wintgens". theaerodrome.com. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ "Lanoe Hawker". theaerodrome.com. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ "Oswald Boelcke". theaerodrome.com. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ "Otto Jindra". theaerodrome.com. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ "Redford Mulock". theaerodrome.com. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ "Eduard Pulpe". theaerodrome.com. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ "Roderic Dallas". theaerodrome.com. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ "Frederick Libby". theaerodrome.com. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ "L'escadrille_37". Albindenis.free.fr. Retrieved 2015-12-17.

- ^ Laurent BROCARD (1914-08-02). "Flying Pioneers : Vieilles Tiges". Past-to-present.com. Retrieved 2015-12-17.

- ^ "Mario Stoppani". theaerodrome.com. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ "Fernand Jacquet". theaerodrome.com. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ "Maurice Benjamin". theaerodrome.com. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ "Thomas Culling". theaerodrome.com. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ "Gottfried von Banfield". theaerodrome.com. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ "Richard Munday". theaerodrome.com. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ "Fritz Anders". theaerodrome.com. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

References[]

- Editors of American Heritage. History of WW1. Simon & Schuster, 1964.

- Cheesman, E.F. (ed.) Fighter Aircraft of the 1914–1918 War. Letchworth, UK: Harleyford, 1960

- The Great War, television documentary by the BBC.

- Gray, Peter & Thetford, Owen German Aircraft of the First World War. London, Putnam, 1962.

- Guttman, Jon. Pusher Aces of World War 1: Volume 88 of Osprey Aircraft of the Aces: Volume 88 of Aircraft of the Aces. Osprey Publishing, 2009. ISBN 1-84603-417-5, ISBN 978-1-84603-417-6

- Herris, Jack & Pearson, Bob Aircraft of World War I. London, Amber Books, 2010. ISBN 978-1-906626-65-5.

- Jackson, Peter The Guinness Book of Air Warfare. London, Guinness Publishing, 1993. ISBN 0-85112-701-0

- Morrow, John. German Air Power in World War I. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1982. Contains design and production figures, as well as economic influences.

- Pearson, George, Aces: A Story of the First Air War, historical advice by Brereton Greenhous and Philip Markham, NFB, 1993. Contains assertion aircraft created trench stalemate.

- Terraine, John White Heat: the new warfare 1914–18. London, Guild Publishing, 1982

- VanWyngarden, Greg. Early German Aces of World War I: Volume 73 of Aircraft of the Aces. Osprey Publishing, 2006. ISBN 1-84176-997-5, ISBN 978-1-84176-997-4.

- Winter, Denis. First of the Few. London: Allen Lane/Penguin, 1982. Coverage of the British air war, with extensive bibliographical notes.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aviation in World War I. |

- Wells, Mark: Aircraft, Fighter and Pursuit, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Morris, Craig: Aircraft, Reconnaissance and Bomber, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Mahoney, Ross & Pugh, James: Air Warfare, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Bombing during World War I at centennialofflight.gov

- Boris Rustam-Bek-Tageev. Aerial Russia: The Romance of the Giant Aeroplane. Рипол Классик. ISBN 978-5-87787-214-1.

- The United States Air Service in World War I – usaww1.com

- The League of World War I Aviation Historians and Over the Front Magazine – overthefront.com

- First World War in the Air at the Dictionary of Canadian Biography

- 1989 WWI aviation documentary featuring interviews with the last three surviving American aces – YouTube

- Aviation in World War I

- 20th-century aviation