Battir

Battir | |

|---|---|

Municipality type C | |

| Arabic transcription(s) | |

| • Arabic | بتير |

| • Latin | Bateer (official) |

Battir | |

Battir Location of Battir within Palestine | |

| Coordinates: 31°43′29″N 35°08′12″E / 31.72472°N 35.13667°ECoordinates: 31°43′29″N 35°08′12″E / 31.72472°N 35.13667°E | |

| Palestine grid | 163/126 |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Bethlehem |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipality |

| • Head of Municipality | Akram Bader |

| Area | |

| • Total | 7,419 dunams (7.4 km2 or 2.9 sq mi) |

| Population (2007)[1] | |

| • Total | 3,967 |

| • Density | 540/km2 (1,400/sq mi) |

| Name meaning | Bether[2] |

| Official name | Palestine: Land of Olives and Vines — Cultural Landscape of Southern Jerusalem, Battir |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iv, v |

| Designated | 2014 (38th session) |

| Reference no. | 1492 |

| State Party | |

| Region | Arab States |

| Endangered | Since 2014 |

Battir (Arabic: بتير) is a Palestinian village in the West Bank, 6.4 km west of Bethlehem, and southwest of Jerusalem. It was inhabited during the Byzantine and Islamic periods, and in the Ottoman and British Mandate censuses its population was recorded as primarily Muslim. In former times, the city lay along the route from Jerusalem to Bayt Jibrin. Battir is situated just above the modern route of the Jaffa–Jerusalem railway, which served as the armistice line between Israel and Jordan from 1949 until the Six-Day War, when it was occupied by Israel. In 2007, Battir had a population of about 4,000.

In 2014, Battir was inscribed in the UNESCO World Heritage Site, as Land of Olives and Vines — Cultural Landscape of Southern Jerusalem, Battir.

History[]

Antiquity[]

Ancient Betar, whose name Battir preserves, was a second-century Jewish village and fortress, the site of the final battle of the Bar Kokhba revolt. The modern Palestinian village is built north east of the ancient site Khirbet el-Yahud (Arabic, meaning "ruin of the Jews" ) and "is unanimously identified with Betar, the last stronghold of the Second Revolt against the Romans, where its leader, Bar-Kokhba, found his death in 135 CE."[3][4][5] "A modern agricultural terrace follows the line of the ancient fortification wall".[4] There is a tradition that the village is also the site of the tomb of the Tannaic sage Eleazar of Modi'im.[6]

A mosaic from the late Byzantine or early Muslim period was found in Battir.[7]

Ottoman era[]

In 1596, Battir appeared in Ottoman tax registers as a village in the Nahiya of Quds in the Liwa of Quds. It had a population of 24 households and two bachelors, all Muslims, and paid taxes on wheat, summer crops or fruit trees, and goats or beehives; a total of 4,800 Akçe. All of the revenue went to a Waqf.[8]

In 1838 it was noted as Bittir, a Muslim village in the Beni Hasan district, west of Jerusalem.[9][10]

French explorer Victor Guérin visited the place in 1863,[11] while an Ottoman village list from about 1870 showed that Battir had a population of 239, in a total of 62 houses, though that population count only included men. It was further noted that it had "a beautiful spring flowing through the courtyard of the mosque".[12][13]

In 1883, the PEF's Survey of Western Palestine described Battir as a moderate sized village, on the precipitous slope of a deep valley.[14]

In 1896 the population of Bettir was estimated to be about 750 persons.[15]

In the 20th century, Battir's development was linked to its location alongside the railroad to Jerusalem, which provided access to the marketplace as well as income from passengers who disembarked to refresh themselves en route.[16]

British Mandate era[]

In the 1922 census of Palestine, conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Batir had an all Muslim population of 542 persons,[17] increasing in the 1931 census to 758; 755 Muslims, two Christians and one Jew, in 172 houses.[18]

In the 1945 statistics the population of Battir was 1,050, all Muslims,[19] with a total of 8,028 dunams of land according to an official land and population survey.[20] Of this, 1,805 dunams were plantations and irrigable land, 2,287 for cereals,[21] while 73 dunams were built-up (urban) land.[22]

Jordanian era[]

During the 1948 war, most of the villagers had fled, but Mustafa Hassan and a few others stayed. At night they would light candles in the houses, and in the morning they would take out the cattle. When nearing the village, the Israelis thought Battir was still inhabited and gave up attacking.[23] The armistice line was drawn near the railroad, with Battir ending up just meters to the east of Jordan's border with Israel. At least 30% of Battir's land lies on the Israeli side of the Green Line, but the villagers were allowed to keep it in return for preventing damage to the railway,[24][25] thus being the only Palestinians officially allowed to cross into Israel and work their lands before the Six-Day War.[26]

Battir came under Jordanian administration following the 1948 Arab–Israeli War and was later, in a move not widely recognized internationally, annexed by Jordan on 24 April 1950 when the Jordanian parliament declared the unification of the two banks.[27]

The Jordanian census of 1961 found 1,321 inhabitants in Battir.[28]

Post-1967[]

Since the Six-Day War in 1967, Battir has been under Israeli occupation. The population in the 1967 census was 1445.[29]

Since the signing of the 1995 accords, it has been administered by the Palestinian National Authority (PNA). Battir is governed by a village council currently administrated by nine members appointed by the PNA. 23.7% of Battir land was classified as Area B, while the remaining 76.3% was classified as Area C.[30]

In 2007, Battir had a population of 3,967,[1] in 2012 the population was estimated at about 4,500.[31]

Geography[]

Battir is located 6.4 km (horizontal distance) north-west of Bethlehem on a hill above Wadi el-Jundi (lit. "Valley of the Soldier"), which runs southwest through the Judean hills to the coastal plain. The PEF's Survey of Western Palestine in 1883 described the city's natural defenses, saying its houses stand upon rock terraces, having a rocky scarp below; thus from the north the place is very strong, whilst on the south a narrow neck between two ravine heads connects the hill with the main ridge.[14] At an altitude of around 760 m above sea level,[30] Battir's summers are temperate, and its winters mild with occasional snowfall. The average annual temperature is 16o C.

Ancient irrigation system and terraces[]

Battir has a unique irrigation system that utilizes man-made terraces and a system of manually diverting water via sluice gates.[25] The Roman-era network is still in use, fed by seven springs which have provided fresh water for 2,000 years.[25][32][33] The irrigation system runs through a steep valley near the Green Line where a section of the Ottoman-era Hejaz Railway was laid. Battir's eight main clans take turns each day to water the village's crops. Hence a local saying that in Battir "a week lasts eight days, not seven."[32] According to anthropologist Giovanni Sontana of UNESCO, "There are few, if any, places left in the immediate region where such a traditional method of agriculture remains, not only intact, but as a functioning part of the village."[25]

In 2007, the village of Battir sued the Israeli Defense Ministry to try to force them to change the planned route of the Israeli West Bank barrier which would cut through part of Battir's 2,000-year-old irrigation system, which is still in use.[24][25] The Israel Nature and Parks Authority (INPA), which approved the fence’s original route in 2005, changed its mind and wrote in a 13-page policy paper that Battir’s terraces were also an Israeli heritage site and should be carefully safeguarded,[34] stating that agricultural terraces around Battir attesting to millennia-old methods of farming in the region will be irreversibly harmed by the fence, no matter how narrow its route. It was the first time an Israeli government agency expressed opposition to the construction of a segment of the fence.[26] This affidavit was one of four expert opinions that contended the fence would decimate the unique farming system, and in early May 2013, the Israeli High Court of Justice ruled that the Defense Ministry must explain “why should the route of the separation barrier in the Battir village area not be nullified or changed, and alternately why should the barrier not be reconfigured.” The Defense Ministry has to submit a new plan for securing the border that will not destroy Battir by July 2, 2013.[34] A separate petition against the separation barrier has also been filed by the nearby Jewish city Beitar Illit, fearing that it would prevent them from expanding the settlement.[35]

In 2011 UNESCO awarded Battir a $15,000 prize for "Safeguarding and Management of Cultural Landscapes" due to its care for its ancient terraces and irrigation system.[24]

In May 2012, the Palestinian National Authority sent a delegation to UNESCO headquarters in Paris to discuss the possibility of adding Battir to its World Heritage List. The PNA's deputy minister of tourism, Hamadan Taha, said that the organization wants to "maintain it as a Palestinian and humanitarian heritage," making special note of its historic terraces and irrigation systems.[36] the nomination of Battir was blocked at the last minute because the formal submission was too late.[32] In a document concerning the damage the separation barrier would do to the area, the Israel Nature and Parks Authority (INPA) noted "The struggle of our neighbors to name the area a World Heritage Site places us in an embarrassing position, and we should work together with them to protect the landscape."[26]

In January 2015, according to the village mayor Akram Badir, the Israeli Supreme Court rejected the IDF request to build the separation barrier through the village [37]

Archaeology[]

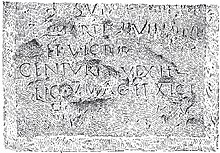

An old Roman bath fed by a spring is located in the middle of the village.[25] Archaeologist D. Ussishkin dates the village to the Iron Age, and states that at the time of the Revolt it was a village of between one and two thousand people chosen by Bar Kochba for its spring, defensible hilltop location, and proximity to the main Jerusalem-Gaza road.[4] A Roman inscription was also discovered near one of the city's natural springs on which are inscribed the names of the Fifth Macedonian Legion and the Eleventh Claudian Legion, which said legions presumably took part in the siege of the city during Emperor Hadrian's reign.[38]

There isn't any evidence of habitation in the period immediately after the Revolt.[4]

Sister cities[]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b 2007 PCBS Census Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. p.116.

- ^ Palmer, 1881, p. 292

- ^ David Ussishkin, "Soundings in Betar, Bar-Kochba's Last Stronghold"

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d D. Ussishkin, Archaeological Soundings at Betar, Bar-Kochba's Last Stronghold, Tel Aviv 20, 1993, pp. 66-97.

- ^ K. Singer, Pottery of the Early Roman Period from Betar, Tel Aviv 20, 1993, pp. 98-103.

- ^ אוצר מסעות - יהודה דוד אייזענשטיין Archived October 2, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dauphin, 1998, p. 911

- ^ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 115

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, 2nd appendix, p. 123

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 2, pp. 324-325

- ^ Guérin, 1869, p. 387 ff

- ^ Socin, 1879, p. 148 It was also noted as located in the Beni Hasan district

- ^ Hartmann, 1883, p. 122 also noted 62 houses

- ^ Jump up to: a b Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, pp. 20-21

- ^ Schick, 1896, p. 125

- ^ A Window on the West Bank, by Bret Wallach

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table VII, Sub-district of Jerusalem, p. 14

- ^ Mills, 1932, p. 37

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 24

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 56

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 101

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 151

- ^ Hans-Christian Rößler (June 21, 2012). "Palästinenserdorf Battir: Widerstand durch Denkmalschutz". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). Retrieved June 11, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Daniella Cheslow (May 14, 2012). "West Bank Barrier Threatens Farms". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f West Bank barrier threatens villagers' way of life. BBC News. 2012-05-09.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Zafrir Rinat (September 13, 2012). "For first time, Israeli state agency opposes segment of West Bank separation fence". Haaretz. Retrieved June 11, 2013.

- ^ "Jordan and the Palestinians:The Creation of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan and the Unification of the Two Banks". Presses de l’Ifpo. 2013. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ Government of Jordan, Department of Statistics, 1964, p. 23

- ^ Perlmann, Joel (November 2011 – February 2012). "The 1967 Census of the West Bank and Gaza Strip: A Digitized Version" (PDF). Levy Economics Institute. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Battir Village Profile" (PDF). The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 17, 2014. Retrieved June 11, 2013.

- ^ "Palestine readying to propose Battir for UNESCO protection". Ma'an News Agency. February 1, 2013. Archived from the original on May 17, 2013. Retrieved June 11, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c A Palestinian Village Tries to Protect a Terraced Ancient Wonder of Agriculture. The New York Times. 2012-06-25.

- ^ Threatened village proposed as next UNESCO world heritage site Archived 2012-12-12 at the Wayback Machine. Ma'an News Agency.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Daniella Cheslow (June 10, 2013). "Land for Peace in the Battle Over Millennia-Old Palestinian Farming Terraces". Tablet Magazine. Retrieved June 11, 2013.

- ^ Ruth Michaelson (March 12, 2013). "Historic Palestinian village fights Israel's separation wall". Radio France Internationale. Retrieved June 11, 2013.

- ^ "PNA intensifies efforts to add more sites to World Heritage list". Xinhua News Agency. May 30, 2012. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ^ 'Israeli Supreme Court rules against separation wall in Battir,' Archived 2015-01-09 at the Wayback Machine Ma'an News Agency 4 January 2015.

- ^ Clermont-Ganneau, 1899, pp. 463-470.

- ^ Britain Palestine Twinning Network. Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

Bibliography[]

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Clermont-Ganneau, C.S. (1899). [ARP] Archaeological Researches in Palestine 1873-1874, translated from the French by J. McFarlane. 1. London: Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Dauphin, Claudine (1998). La Palestine byzantine, Peuplement et Populations. BAR International Series 726 (in French). III : Catalogue. Oxford: Archeopress. ISBN 0-860549-05-4.

- Government of Jordan, Department of Statistics (1964). First Census of Population and Housing. Volume I: Final Tables; General Characteristics of the Population (PDF).

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945.

- Guérin, V. (1869). Description Géographique, Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine. Judee, Vol 1, pt 2, part 1.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Centre.

- Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. 2. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Schick, C. (1896). "Zur Einwohnerzahl des Bezirks Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 19: 120–127.

- Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163.

External links[]

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (June 2018) |

- Welcome To Battir

- Battir, Welcome to Palestine

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 17: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Battir Village (Fact Sheet), Applied Research Institute–Jerusalem (ARIJ)

- Battir Village Profile, ARIJ

- Battir Village Area Photo, ARIJ

- The priorities and needs for development in Battir village based on the community and local authorities’ assessment, ARIJ

- www.battir.i8.com

- Battir village photos

- Battir Video

- World Heritage Sites in the State of Palestine

- Seam Zone

- Bethlehem Governorate

- Towns in the West Bank

- World Heritage Sites in Danger

- Municipalities of the State of Palestine